Stella Kalinina for the National Young Farmers Coalition

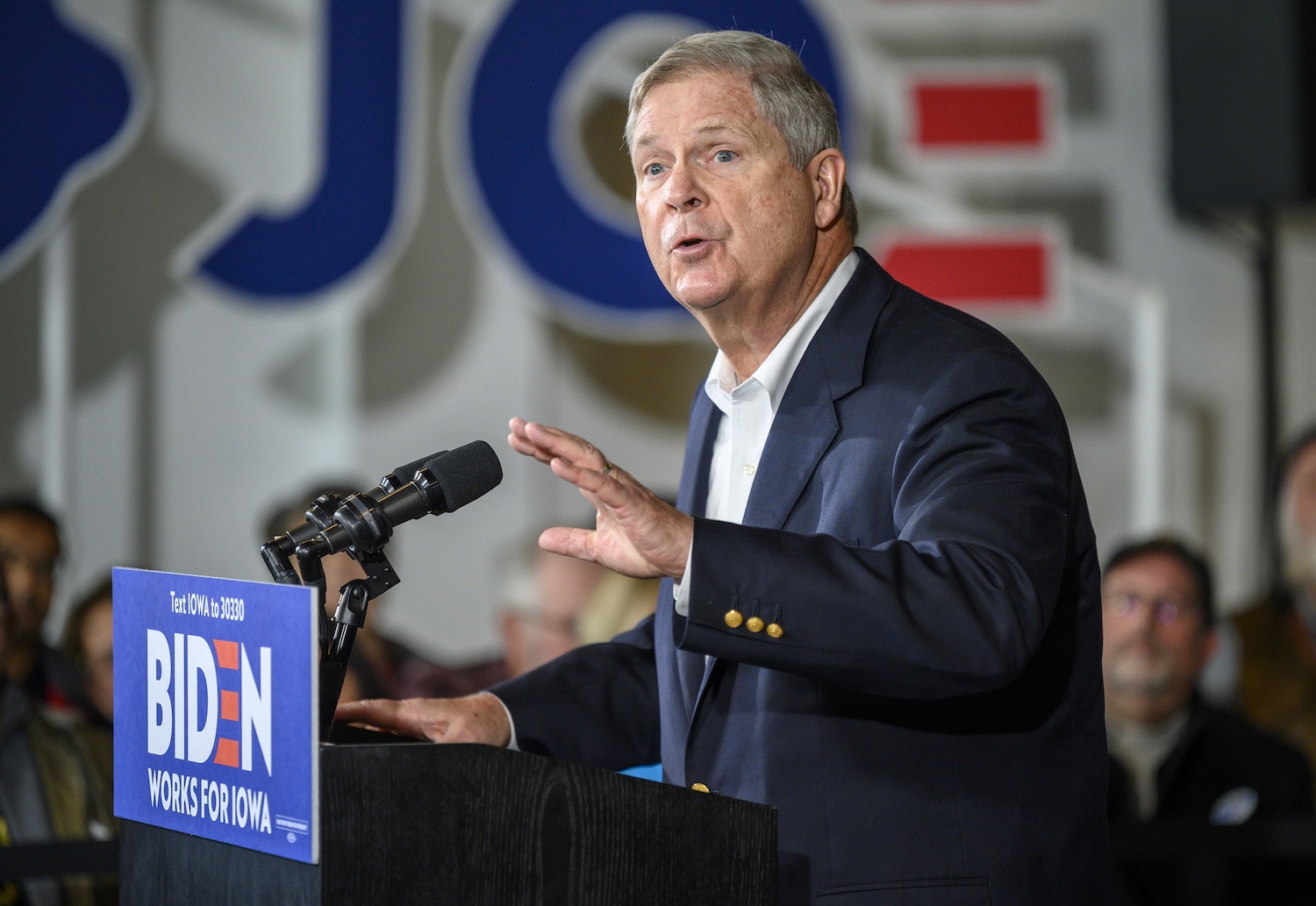

Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack appeared before the Senate in an easy confirmation hearing this week. But to many, he represents a status-quo-focused USDA in desperate need of modernization. Here’s the roadmap to a “people’s agency” for the future.

If you get your news from USDA economic reports, 2020 was a great year.

But that is the story as told through statistical averages and industry data sets—a story far removed from the lived experience of our farming communities and the general public. That version of the story leaves out last year’s supply chain disruptions and extending food lines, rendering invisible the overworked, stressed, and threatened lives of vulnerable communities in the fields, the factories, and in our neighborhoods. The question remains: How do we have an agricultural economy so disconnected from our public reality?

We can point to bright spots of caregiving and sustenance that result from a community-supported agricultural system. But too often these thrive despite a public-supported agricultural system that protects a national economic interest but does not equitably distribute benefits to the broader public or offer protections to wanting communities.

We want our “people’s agency.”

As a new administration steps in to manage the United States Department of Agriculture, we must recognize it is managing more than the 29 agencies and 100,000 staff that make up the USDA. It determines our collective relationship with the land, defines the legacy of agriculture, and bears responsibility for our safe passage through the climate catastrophe. And this new administration manages a system of publicly-supported agriculture that has not always served our public interest. Secretary of Agriculture nominee, Tom Vilsack, who is expected to be confirmed by the Senate on Tuesday with little to no friction, is faced with the task of re-aligning our public agriculture with the public good by helping to rewrite the social contract that dictates our agricultural system. It’s a task that will need partners and full public support.

We need to challenge a concept of trickle-down farm policy that serves a select few.

We need a USDA that honors our interest in participating in our future and truly represents the farming communities it often praises. Our coalition of farmers is ready to advocate for a new paradigm in farm policy—one that prioritizes the public interest, dismantles the white supremacy that dictates obsolete notions of farming, and prepares us for climate catastrophe by placing our resilience firmly in service to our communities. We need a commitment to inspect the foundations of an agricultural system that has taken so much from our communities without adequately providing in return. We need to challenge a concept of trickle-down farm policy that serves a select few. We require clear-eyed assessments and actionable plans for our shared resilience. We want our “people’s agency.”

As we look forward to the future of USDA, here’s where we’re at, what we can leave behind, and where we should all want to go.

The United States Department of Agriculture building in Washington, D.C., as seen at night in 2015.

Jonathan Newton / The Washington Post via Getty Images

Farming should be in the public interest. It is the provider of our health and nutrition, how we steward half the country’s land, the direct employment of 3 million people, and indirect employment of another 20 million people who work in food-related industries. Farming is foundational to our collective well-being, an expression of culture, the core of our self-determination as a people.

But the public interest is not being served. Food is our daily sustenance and yet we’re in a hunger crisis impacting 27 million people, including one in four children. Food is a determinant of our health and potent medicine, but we endure an epidemic of malnutrition that instead makes food a contributing risk factor in the majority of illnesses that cause our death. Each year, our farmland erodes at the same pace as during the Dust Bowl while being simultaneously consolidated in the portfolios of an increasingly select few and locked out of reach to new generations.

Residents of New York City join a queue to receive food donated by local organizations during the Covid-19 pandemic. The current hunger crisis impacts 27 million people in the U.S., including one in four children.

An entire workforce enabled by agriculture and devoted to our nutrition is as vulnerable as it is essential. Workers in food preparation and farming occupations take home a less-than-living annual wage of $26,670 and $31,340, respectively. And 75 percent of the agricultural workforce is denied the basic protections that citizenship provides and their contributions deserve.

The public experience of agriculture does not correspond with the economic reports of the farming industry. It is not simply that we have a system of agriculture that fails the public interest by depleting land and people. The public’s experience is so divergent from the economic success indicators of the farm industry that last year saw net farm income at its highest in seven years. Just as we have a stock market that is not our economy, we have a farm economy that is increasingly detached from the realities of farming and the experience of farming communities.

This detachment has everything to do with public policy. It’s a long story with a new chapter every year. In 2020, a series of new and long-standing government relief programs were responsible for nearly 40 percent of the farm income spike. This windfall did not come from Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, or accessing Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL), or even the stimulus checks that were made available to U.S. residents and denied to our undocumented community members. This windfall was a combination of direct farm payment programs dating back to the Great Depression, topped up with a novel relief program, the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP).

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

CFAP unlocked billions of dollars in new government funding to help farmers “absorb” their pandemic-related losses. The National Young Farmers Coalition, of which I am co-executive director, campaigned to make this funding available to local food producers who also faced downturns due to restaurant closures and lost markets. Instead, the funding approved by Congress was largely made accessible to the usual recipients of direct farm payments: large, land-owning farms and commodity producers.

Government programs meant to help support agriculture during disasters have hardened the agricultural system to depend on crisis.

It was an entirely logical program based on outdated data that disregarded the new business models and production practices of a new generation of farmers. We launched another campaign after the initial implementation of CFAP to hold USDA accountable to the letter of the CARES Act, advocating for a second round (“CFAP2”) that would make this funding more accessible to young farmers and farmers of color. The adjustments we won enabled many of these farmers to receive relief funding roughly equivalent to 10 percent of their 2019 sales. It was a lifeline for farmers who don’t expect support from the USDA, but it doesn’t compete with the billions of dollars shifted to industrial agricultural interests or the 40 percent of farming industry income that came directly from government support. And the program did not fulfill our demands for direct relief to farm workers or expanded hazard pay or a commitment to better reporting on program payments. Our best version of agriculture remains, unfortunately, mostly community-supported instead of public-supported.

The U.S.’s public-supported agriculture can sometimes lose sight of the public interest. Government programs meant to help support agriculture during disasters have hardened the agricultural system to depend on crisis. Public dollars can be directed without adequate accounting for public benefit. Our public agricultural system has been exposed too many times with unclear goals and objectives undertaken through programs of unequal distribution, selective austerity, and intentional discrimination. It can be a confusion of trickle-down economics and elegies to the “great patriot” farmers. Exceptions go a long way toward investing in the next generation of farming enterprises but they remain largely exceptions. Public agriculture for private gains has not been entirely to the benefit of the public.

Recent funding approved by Congress was largely made accessible to the usual recipients of direct farm payments: large, land-owning farms and commodity producers.

Don and Melinda Crawford / Getty Images

Our public agriculture falters when the USDA restricts the constituency of its agricultural support to “farmers.” That definition is both conditioned by its relation to wealth and whiteness, and rapidly becoming obsolete. Nearly 100 percent of funding designed to offset farm losses in the trade war “won” by President Trump benefited white farmers. The USDA has not adequately collected or provided accounting for the demographic beneficiaries of its other programs. But agricultural programs primarily serve farmland owners and “primary producers”—defined by USDA as the individual who made the most decisions on the farm. And with both groups over 95 percent white, a reckoning with the ways that farming is a consolidation of racial privilege is long-overdue. But expanding definitions or bolting “farmers of color” onto policy will be insufficient without material concessions, a commitment to reparations, and the full restoration of Indigenous relationships to land.

Public agriculture for private gains has not been entirely to the benefit of the public.

Meanwhile, with the average age of primary producers now almost 60 years old, the narrowing profile of who is a “farmer” underscores this contradiction: an industry premised on regrowth is now reluctant or unable to foster a new generation of growers and a next generation of agriculture. Our collective admiration for “family farms” and farm ownership ignores survey data showing that many young and beginning farmers are not coming from a farming family and are often working in new collective models. And for too long the USDA has ignored the contributions, knowledge, and talents of farm workers and considered them a labor issue for the “real farmers” to solve. If states can find ways to get Covid-19 relief to undocumented farmers, then USDA can use its authorities to support the millions of those farmers who contribute to our food system but are overlooked by current policy.

Any attempt to modernize our agricultural system and align with the public interest will fail without a comprehensive land access strategy. That Bill and Melinda Gates are now this country’s top owners of farmland in the United States—and by USDA’s current logic, our best farmers—underscores the looming land crisis at the heart of U.S. agriculture. Nearly two-thirds of our farmland will change hands over the next decade at a time when the worsening climate crisis requires that we preserve this community resource for necessities of equitable food access.

The USDA must take an active role in the massive land transition currently underway. And the USDA must make available all its resources towards this transformation and exert an unprecedented level of diligence and moral imagination.

For too long the USDA has ignored the contributions, knowledge, and talents of farm workers and considered them a labor issue for the “real farmers” to solve.

We know that farmland will be our higher ground as the climate crisis worsens. But the agricultural use, environmental benefits, and social priorities for farmland can’t compete with a system in which food production is merely a byproduct of farmland, in which land is solely a destination to park wealth and watch it grow. This country has a long history of land dispossession and land theft but no experience in encouraging equitable land access. Land will continue to be either managed with the same biases as our subsidy system or neglected for private capital to monopolize. Without concerted and multiple land policy interventions, we forestall the more just food system that is struggling to be born. We might expect some meek adjustments, but too little investment would expose how much of our agricultural policy is a land-wealth preservation strategy.

A land ownership crisis looms at the heart of U.S. agriculture—in which land often functions solely as a destination to park wealth and watch it grow.

Mario Tama / Getty Images

An agriculture in the public interest will also depend on moral imagination and a more optimistic perspective on rural opportunities. The USDA is tasked with rural development and has billions of dollars available to help improve the economy and quality of life in the rural U.S. Through its Community Facilities program, the department has played a critical role in financing rural healthcare systems despite the vulnerabilities the pandemic is revealing. But the Community Facilities program has also invested more than $700 million in rural law-enforcement infrastructure over the last 20 years—four times what it has invested in local food infrastructure and mental health services during that same period.

After the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and seeing a new willingness to investigate police accountability, I began to research and track where those dollars landed. Patrol cars were financed for a department in Butler, Georgia, where an officer had been suspended for posting racist comments on Facebook. Investments were made in a police department in White, Georgia after the city manager and police chief were indicted for corruption. Just last year, $89 million in total was allocated to rural law enforcement and prison systems: in Fayetteville, Pennsylvania, for instance, $51 million was earmarked to finance a new county prison and replace an aging building with “serious compliance issues.” Two months before the press release on that, 30 Fayette County prison officials were indicted by a grand jury after a 7-month investigation into alleged corruption and a drug ring inside that very facility.

Too little investment in equitable land access would expose how much of our agricultural policy is a land-wealth preservation strategy.

A USDA committed to responsible fiscal management would immediately cease funding rural law enforcement. A USDA committed to racial justice and optimistic about rural communities would imagine better. A USDA that served the public would let the public decide.

Moral imagination requires a new and unprecedented commitment to transparency and the flow of public dollars. Most members of the public are unaware that the pacemaker at the heart of U.S. agriculture is the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), a wholly-owned government corporation with no employees, that holds no real assets, and is designed to run multi-billion dollar losses and post no return on equity. It is a corporation that has, since 1933, been responsible for over $1.1 trillion in direct government payments to farmers with only the current agricultural system to show for it. A trillion dollars over 88 years: that’s the equivalent of purchasing the entirety of our country’s farmland. (The forecasted $46 billion in direct farmer payments distributed in 2020 is equivalent to the total value of Northeast cropland and more than the market capitalization of ADM and Bunge—two of the three corporate monoliths of U.S. agriculture.)

A USDA committed to responsible fiscal management would immediately cease funding rural law enforcement. A USDA committed to racial justice and optimistic about rural communities would imagine better.

The CCC is a governmental tool of immense financial power. But this is machinery without direction and machinery only in parts. With an aligned and integrated approach to public agriculture, the USDA could engineer a competitive and public option for agriculture. A CCC employed to address the climate crisis and land transition could be transformational. A revised focus on land could help place millions of acres in public trust, a renewed commitment to farmer livelihoods could help finance a new civil sector of farmers compensated at a living wage or provide a retirement plan for aging farming communities, and aligning production with an investment in supply chain infrastructure could see USDA deliver food security to this country.

Or better yet, the USDA could listen to long ignored communities to decide the next generation of agriculture. Indigenous and Black communities that are expert in resilience could direct the future of USDA programming: Communities of color resourced to plan and implement the landscape vision that climate resilience requires, with the money and time and safety that visioning demands. Farm workers could design the scaling up of existing collective labor efforts and realize new models of worker-ownership. Land stewardship could be facilitated with a significant investment in multi-generational land transfer and mentorship. And the staff of USDA could be empowered to exercise their expertise and express the agency’s capacity for science-based decision-making. Transformation requires time and thinking. We are not advocating for urgency but for intention.

Justin Butts, livestock manager at Soul Fire Farm in Petersburg, New York, September 20, 2020. There are only 45,000 Black farmers—1.3 percent of all agricultural producers—while Black people are about 13 percent of the population, according to census data.

AFP via Getty Images

With the government and USDA under new management, now is the time for change. Regardless of expectations, there is a public sector responsibility to resolve the contradictions that position farming at the expense of the public interest. This resolution is not a question of adjustment but of bold transformation. The USDA will need to re-define success and reorient agriculture to advance racial justice, climate action, and public health.

This demand for transformation is mostly a simple request for USDA to recommit to diligence and express the moral imagination we need to realign our agricultural system with the public interest. We know the inertial force of long-standing policy, the cautious whiteness, and conservative bend of the narrowly-defined “farmer” constituency. But we also know there is a groundswell for bold change.

We know the inertial force of long-standing policy, the cautious whiteness, and conservative bend of the narrowly-defined “farmer” constituency. But we also know there is a groundswell for bold change.

There is a movement of community-supported agriculture that has, from necessity, emerged to address the failings of a public-supported agriculture. We need a USDA that invests in this agriculture, that puts public funding toward community agriculture that works for the public instead of patching a system that functions in opposition to our interests. We want a farm future that is uncompromising on racial equity and climate action and public health. And more than the right to land and wealth we want the responsibility of stewardship and community building. A generation of young farmers wants to participate in agriculture without having to perpetuate what is incongruent with our communities’ well-being. We are ready for USDA to align public-agriculture with the public interest. And we are ready for USDA to follow our lead.

Together we can stop speaking of the USDA and start rebuilding our USDA.