Aanika Biosciences

In most cases, the source of an outbreak is never found. New biotechnology is promising, though food safety experts remain skeptical.

In 2017, Vishaal Bhuyan launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise money for a snack business that utilized water lily seeds. He raised more than $25,000, but ran into issues with his supply chain. The raw ingredients, imported from India, were contaminated with insect debris, pesticides, and preservatives banned by the FDA.

“The supply chain was so bad that everything had to be thrown out,” said Bhuyan. To solve the problem, he made a career pivot, enrolling in a crash course on genetic engineering at GenSpace, a nonprofit, community laboratory in Brooklyn. There, he met Ellen Jorgensen, a leading figure in the do-it-yourself biology movement, who has a doctorate in molecular biology.

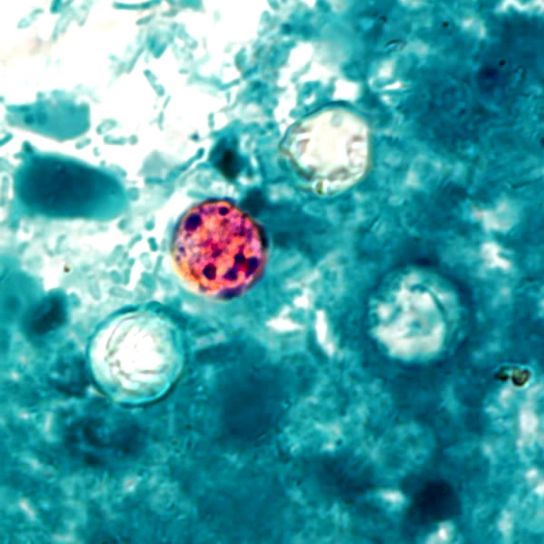

Jorgensen and Bhuyan teamed up to co-found Aanika Biosciences, a Brooklyn-based biotechnology company that says it’s able to quickly identify the source of foodborne contaminations—or pathogens—by using genetically engineered bacterial spores that cling to food. Their spores contain DNA barcodes that can be “scanned” to identify a food’s origin, down to a plot of land on a farm. But food safety experts are skeptical that the technology will be widely adopted, citing privacy concerns for farmers and fears of food tampering by consumers.

Water lily seeds, which Bhuyan used to make his snack chip, are destroyed. Aanika Biosciences claims that their technology can trace the source of foodborne contaminants and pathogens.

Aanika Biosciences

According to Bhuyan, here’s how this spore technology works: Bacteria are first genetically engineered with a unique DNA barcode, and then coaxed into a vegetative state that makes the bacteria resistant to a slew of environmental onslaughts. These spores can be added to water and attached to crops as they are being washed. Then, as the plants move through the supply chain—from farm to harvester to distribution center—the genetic barcodes within each spore can be “scanned” to identify where each plant came from.

“We can now test a leaf, find which serial number is on that leaf, and which farm that corresponds to,” said Bhuyan. The whole process takes under an hour, according to a blog post from the company.

Currently, Aanika’s technology is being sold directly to companies who use those bioengineered spores, internally, to identify the source of contaminants or pathogens in their food products, Bhuyan said. The spores are still in a testing phase and haven’t been rolled out at a large scale.

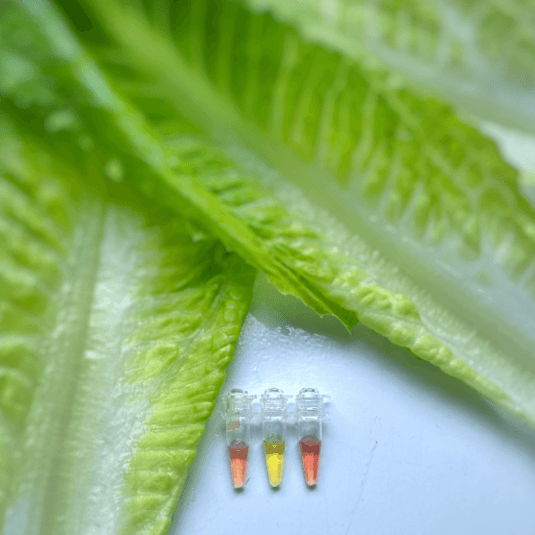

Bioengineered spores can be sprayed directly onto plants or can be added as leaves are washed after harvesting.

Aanika Biosciences

Many technical details about these spores—such as how they’re “scanned” or genetically modified—were not disclosed during our interviews. But a research study from June 2020, in the journal Science, lends some insight into the technology.

In that study, researchers at Harvard Medical School took 18 different plants and sprayed each of them with bioengineered spores containing unique, genetic barcodes. More than a month later, the researchers collected leaves from each plant, mixed them all together, and sequenced the DNA barcodes residing on each leaf. The scientists were able to pinpoint the specific plant that each leaf came from, based on the sequence of those molecular blueprints. The spores were also resilient to environmental threats—they remained on the leaves after being washed with water, boiled, fried, and microwaved.

Aanika’s spores are different in some regards, according to Bhuyan, but he was not willing to provide further details. In a company blog post, Jorgensen said that—similar to the Harvard study—the company’s spores clung to plants even after being “washed in running water for several minutes,” and weren’t “destroyed by microwaving, frying, or steaming.”

“If a piece of lettuce is contaminated and carries our barcode it would be difficult to deny responsibility even through mixing and washing.”

Some people might be wary of eating bioengineered spores, but Bhuyan asserts that they are “food safe” and that, to make them, his company uses the same bacterium—called Bacillus subtilis—already found in probiotic yogurts sold on the market. Another company, called SafeTraces, also offers a genetic-based food tracing system, but uses naked DNA instead of bacterial spores.

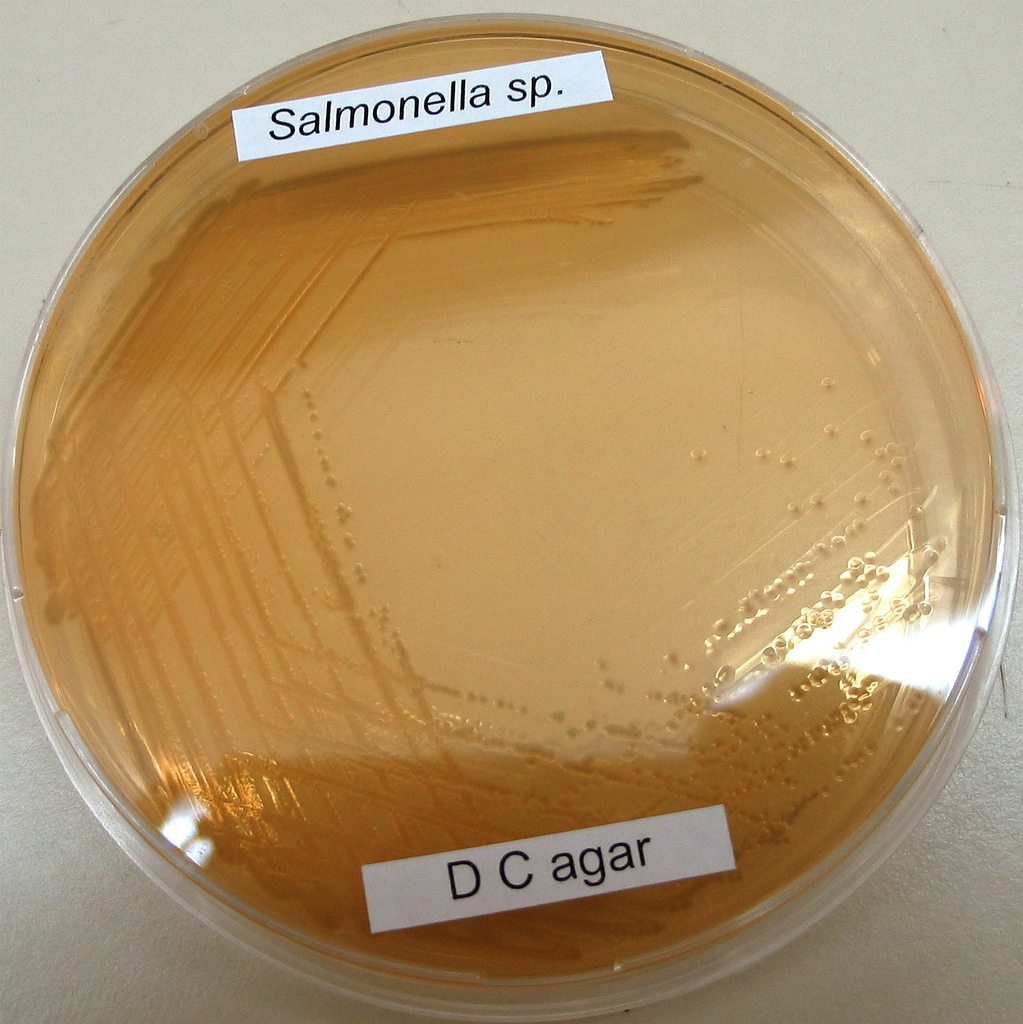

Consumer concerns aside, if Aanika’s spores were to be rolled out at scale, they could help speed up foodborne outbreak investigations that, today, are logistical nightmares. After a large romaine lettuce outbreak in 2018 led to nearly 100 hospitalizations, the FDA wrote in a statement that their investigation required the collection and evaluation of thousands of records “to accurately reproduce how the contaminated lettuce moved through the food supply chain to grocery stores, restaurants and other locations where it was sold or served to the consumers who became ill.” It took the FDA roughly six weeks to identify the California counties responsible for the outbreak.

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

During their investigations, the FDA also interviews people who get sick to identify common foods that might be responsible for their illnesses. Documents go missing, though, and people don’t always remember what they ate yesterday, let alone last week. The source for most foodborne outbreaks is never solved, according to a 2019 study.

The company has been testing spores designed specifically for lettuce, which the company said is “virtually indestructible” and stuck to the plants even when they were washed with water, microwaved, fried, or steamed.

Aanika Biosciences

Foodborne diseases also kill about 3,000 Americans every year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Besides the cost of life, the investigations that result—as well as the product recalls and damage to a company’s public image—can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, according to a USDA estimate. Maybe Bhuyan’s technology can alleviate some of that damage, and help to quickly identify the farmers responsible for an outbreak.

That’s the goal for Barbara Kowalcyk, at least, who lost her 2-year-old son, Kevin, to a foodborne illness in 2001. “He went from perfectly healthy to dead in 12 days,” she said.

Aanika Biosciences

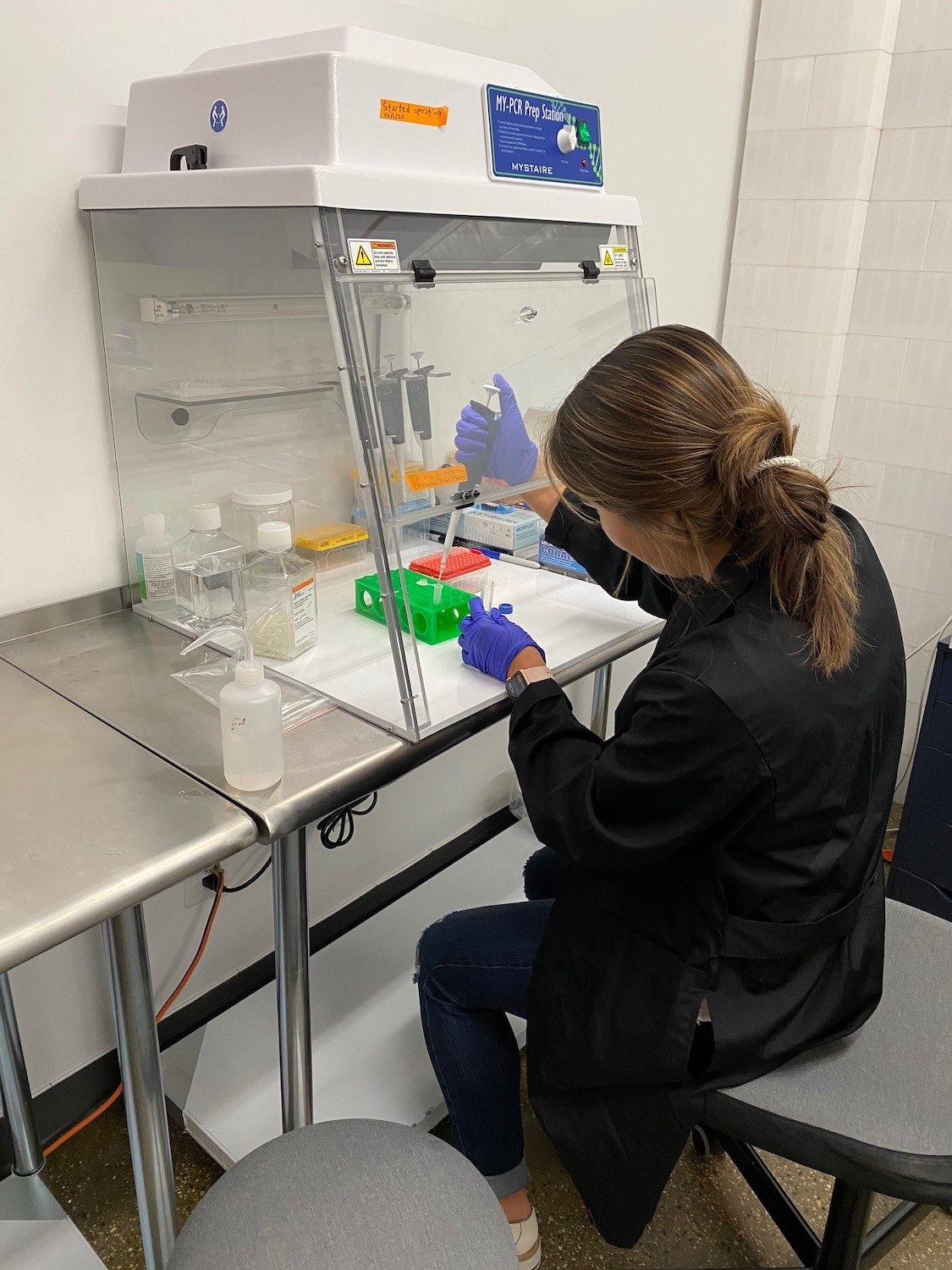

An Aanika intern, Emily Demmon, performs an experiment in a clean chamber.

In her case, the county public health department showed up to the hospital where Kevin was being treated, interviewed Kowalcyk and her husband, collected some stool samples, and left. They never launched a thorough investigation, Kowalcyk wrote in an article after her son’s death. The investigators purportedly told her that “the chances of accurately identifying the source of Kevin’s illness were less than 5 percent.”

Frustrated, and hoping to identify the source of her child’s pathogen, Kowalcyk launched her own investigation. Six months and several legal threats later, she obtained documents that allegedly revealed that the DNA pattern from her child’s E. coli infection matched meat from a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) recall issued in August 2001. She filed a lawsuit but, unable to prove liability, later dropped the case. Kowalcyk went back to school, got a doctorate degree, and now runs the Center for Foodborne Illness Research and Prevention at Ohio State University.

Bhuyan, at least, thinks that his technology could have helped to prove liability for Kowalcyk. “Our tags are molecular fingerprints,” he said. “If a piece of lettuce is contaminated and carries our barcode it would be difficult to deny responsibility even through mixing and washing.”

But food safety experts expressed skepticism that Aanika’s tracing data would even be accessible to people in the event of an outbreak.

“If production or traceability data is more freely available, it could enable buyers to have more power in negotiations.”

“I am sure that information would be difficult to obtain as a private party,” said Steven Venette, a professor at the University of Southern Mississippi who studies crisis communication and who previously worked at the USDA, the federal agency tasked with overseeing meat, egg, and poultry outbreaks. “It would be somewhat like calling Nike and asking which employees made your shoes. They are only going to take the time to do that if someone of authority requires them to do so.”

Venette thinks that the real challenge for Aanika’s technology will be to convince farmers and consumers to adopt the technology in the first place. “We do not like people messing with our food,” he said. “If you tell people you are spraying crops, people will believe all kinds of crazy conspiracy theories.”

Farmers, too, will have their own concerns when it comes to adopting a new tracing technology.

The information contained within the spores found on a lettuce leaf, shown here, can be retrieved using molecular biology techniques to determine where each plant came from.

Aanika Biosciences

“I am sure that some producers do not want traceback because they are worried about liability,” said Venette. “Some may be concerned about being held responsible for issues that occur after the product has left their control. A rancher would be upset if meat products contaminated with E. coli was traced back to her ranch if the contamination happened at the processing facility, for example.”

Traceability data could also hurt farmers when it comes to negotiating with buyers, according to Thomas Burke, the senior food traceability and safety scientist at the Institute of Food Technologists.

“If production or traceability data is more freely available, it could enable buyers to have more power in negotiations,” he said. Grocery chains and restaurants, for example, could demand that the food they buy be traceable back to a farm, a request that would be financially untenable for smaller growers. Burke also said that “there could be some concern that providing data will increase liability for farmers and give justification for additional regulatory oversight.”

“I think that producers would welcome traceback if there is an economic incentive for them to participate.”

Prior efforts to impose tracing rules on farmers have failed for some of these reasons. For years, the USDA has been trying to get RFID tags implanted into cattle ears, which would allow meat samples to be traced back to their origin. That effort is still being negotiated with cattle farmer advocacy groups, who have been reluctant to adopt it due to data privacy concerns. In July, the USDA published a notice, pushing for a federal requirement that would require RFID tags for beef and dairy cattle by Jan. 1, 2023, to help trace disease outbreaks.

The main way to get farmers on board with tracing systems, according to Venette, is not to impose some mandatory tracing rule but, rather, to demonstrate that the spores offer a clear, economic incentive for farmers.

“I think that producers would welcome traceback if there is an economic incentive for them to participate,” he said. “If McDonald’s said that it would not purchase beef that was not traceable, traceback would be implemented overnight.” (McDonald’s is one of the largest purchasers of beef in the world, according to the company’s website.)

A normal food recall can affect a dozen farms, some of which were not actually responsible for the outbreak. Instead of recalling produce from all those growers, Aanika’s spores could instead be used to pinpoint the outbreak’s source, reducing the number of claims paid out by an insurance company.

Bhuyan said that his company has plans to win over both farmers and consumers, and that many industries have already signed on to use the technology.

“The traction we have gained spans multiple countries and supply chains ranging from meat, dairy, cannabis, coffee, leafy greens, and a range of non-organic items,” he said. It’s unclear which companies Aanika is currently working with, as only a handful of partnerships—including a collaboration with the diamond company, De Beers Group—have been disclosed publicly.

A normal food recall can affect a dozen farms, some of which were not actually responsible for the outbreak. Instead of recalling produce from all those growers, Aanika’s spores could instead be used to pinpoint the outbreak’s source, which would have the additional benefit of reducing the number of claims that an insurance company would have to pay out. This year, Aanika will work directly with agricultural insurers, offering them up to $10 million in guarantees, an incentive to protect insurers against loss in case claims submitted to them by farmers are not reduced as a result of using Aanika’s spores. The move was made public in a blog post that the company posted to Medium in December, and it could offer enough of a financial incentive to get more large-scale traction with farmers.

As for consumer concerns, Bhuyan said that, even if spores did end up on your dinner plate, the average person poops out thousands of bacterial spores every day—a claim supported by a recent study—“so we don’t think this will be a problem.”