The Trump administration implemented a rule that stripped away environmental protections for streams and wetlands. The Jemez Pueblo and Laguna Pueblo tribes argue that this has jeopardized their food systems and cultural practices.

Two Indigenous tribes are suing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) over a Trump-era rule that rolled back protections on waterways crucial to their farming and cultural practices.

The Jemez Pueblo and Laguna Pueblo tribes, which are located in what is now New Mexico, filed a lawsuit in late March calling on a federal court to toss the Navigable Waters Protection Rule—a Trump administration move that narrowed the definition of federally protected waters to explicitly exclude sources that result from rainfall or seasonal snowmelt. As a result of the regulation, companies no longer have to obtain permits to discharge pollutants into these ephemeral streams, as they’re known. It also allowed property owners to destroy and fill in wetlands for construction projects.

According to the EPA’s own estimates, more than 18 percent of streams in the U.S. are ephemeral. This is especially the case in dry regions like New Mexico. As a result, the lawsuit argues, the rule disproportionately harms the Jemez and Laguna Pueblos by eliminating protections for water sources that they depend on.

“Hundreds of miles of ephemeral streams that support the Pueblos’ agriculture, recreation, and cultural and spiritual practice are now at imminent risk of degradation and destruction without federal protection,” the lawsuit reads.

“Farming is a way of life for us. That is threatened if this EPA regulation that was done away with during the Trump administration is not put back into the books.”

Under Trump, the EPA put the Navigable Waters Protection Rule into place after repealing a previous Obama administration policy known as Waters of the United States (WOTUS), which had protected streams, tributaries, and wetlands that feed into larger, permanent water bodies. In doing so, the lawsuit estimates that the rule did away with federal protections for up to 97 percent of stream miles in Laguna Pueblo territory and 87 percent for the Jemez Pueblo. (EPA did not respond to a request for comment by press time.)

For Chris Toya, a farmer and enrolled member of the Jemez Pueblo tribe, the Navigable Waters Protection Rule directly jeopardized tribal food systems and customs. Toya, who is also the tribal historic preservation officer for Jemez Pueblo, said that he and most of his fellow tribal members are small-scale farmers.

“Farming is a way of life for us,” he said. “That is threatened if this EPA regulation that was done away with during the Trump administration is not put back into the books.”

“Currently, the EPA can’t regulate any person or business that is polluting these drainages and tributaries.”

Toya grows a variety of crops including grapes, melons, squash, and chiles on his farm, and he irrigates it with water from the Jemez River, which is connected to tributaries, drainages, and gullies formed by recurring streams of water called arroyos.

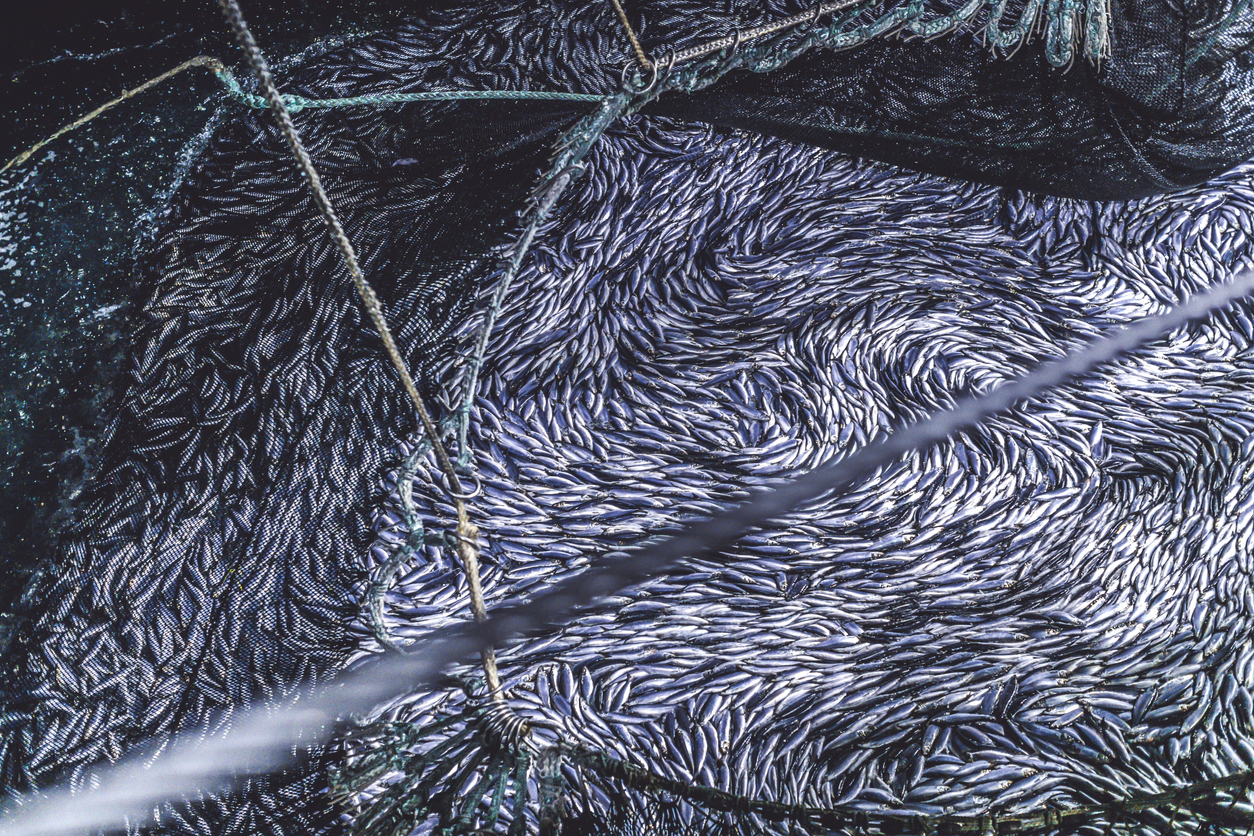

“Currently, the EPA can’t regulate any person or business that is polluting these drainages and tributaries,” said Toya. “And then when it rains, those pollutants go into our river.” He also pointed out that he and fellow tribal members eat fish caught in the Jemez River, and use water drawn from it in ceremonies.

President Trump signaled his interest in repealing WOTUS almost immediately after taking office. In February 2017, he directed then-EPA administrator Scott Pruitt to begin a review of the rule, with the ultimate goal of repealing it altogether. The move was welcomed by agriculture lobby groups like the Farm Bureau, which had opposed WOTUS on the argument that it burdened farmers with regulation on private property. (WOTUS carved out exemptions for most farming activities.)

“The test was not whether water runs year round, the test is whether pollution in one area can have a significant nexus to water pollution in another area.”

But environmentalists and small-scale farmers like those in the Pueblos argue that the interconnected nature of water systems necessitates broad protections. The tribal plaintiffs in this case want to see the current rule vacated, and for the EPA to regulate waters based on what’s known as the “significant nexus” test—criteria put forth by former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy that would determine whether a wetland falls under federal jurisdiction based on its linkages with other regulated waters.

“The test was not whether water runs year round, the test is whether pollution in one area can have a significant nexus to water pollution in another area,” said Clifford Villa, associate law professor at the University of New Mexico and attorney for the plaintiffs.

The Biden administration is currently reviewing the Navigable Waters Protection Rule. Even if it decided against defending the rule in court, other third-party proponents of the regulation could jump in and do so in the government’s place, Bloomberg Law points out.

Meanwhile, Toya is starting to think about which crops to plant this year. In a few months, monsoon season will descend on the region and fill its dried ephemeral streams back up.

“Once it rains, you have the water, the irrigation, the fields being flooded with water,” said Toya. “Flooding in the sense that it’s not devastating, but flooding in the sense that it’s helping plants grow.”