Trisha Kostis

The ban on indoor gatherings hits assisted-living residents hard, as they retreat to their rooms when they’d rather be dressing for dinner.

The dining room I supervise bears a sorry resemblance to a furniture showroom close-out sale these days, with boxes stacked along the walls, tables pushed to the four corners of the cavernous space, and chairs stacked in a geometric pile. This used to be the frenetic nucleus of the Ballard Landmark, a senior and assisted living community in Seattle, Washington where I am the corporate culinary director. Since last March, it’s been stripped of its primary purpose, to provide meals – and a sense of community – to 150 vital seniors now held captive in their rooms.

Adults 65 and older come to senior and assisted living for reasons as varied and plentiful as the pills in their medi-sets. But once they have moved in, the predominant unifying theme is the desire for companionship. The dining room has the gravitational pull of the sun, providing a fertile environment for the seeds of new friendships. While some residents join in activities such as exercise classes or book clubs, everyone participates in meals three times a day, and spends even more of the day preparing for those meals — choosing tablemates and a time to eat and selecting the perfect outfit. Many bring the news of the day, possibly scribbled in pen on a recycled menu or envelope, as a conversation starter. Others bond over heated discussions about crisp versus soft vegetables and the near impossibility of making a moist skinless and boneless chicken breast.

The closed dining room at the Ballard Landmark, an assisted living community in Seattle, Washington.

Trisha Kostis

When we were forced to close communal dining in March of 2020, we believed it was a temporary remedy to an emergent danger. The senior housing industry is already familiar with the “pivot” because flu, norovirus, and other contagious illnesses are an ongoing threat to congregate settings. We are always prepared; we packaged meals in cardboard boxes and traversed the six floors of the building delivering tepid food to frightened residents, reassuring them this unpleasant disruption to their routines would be short-lived.

We didn’t imagine that a year later there would still be a velvet rope across the entrance of our dining room, and we would be handing off to-go boxes to octogenarians like we were Uber Eats drivers.

Creating meals that satisfy hundreds of residents, many of whom are unhappy for reasons that have nothing to do with food, is not a task for the fragile, as we try to navigate their cultural preferences and dietary challenges on a budget leaner than an eye round roast. My staff and I are equal parts culinary wizards and mad scientists – and even so, sometimes satisfying a resident means little more than making sure their favorite yogurt or ice cream is available. Because their lives are unreliable in so many ways, we strive to ensure that good food is a constant.

The dining room has the gravitational pull of the sun, providing a fertile environment for the seeds of new friendships.

Another big part of our jobs involves personal relationships. We encourage staff members who are on break to spend some time eating with the residents. A ten-minute chat on the patio with someone who was dissatisfied with the soup may well be the only conversation that person has all day. But with the pandemic restrictions, opportunities for the culinary staff to engage have dwindled to quick exchanges at apartment doors held nervously ajar.

For one year, mothers and fathers, grandparents and great grandparents have pressed their trembling hands against rain-splattered windows to make some kind of contact with their families. Holidays, birthdays, and anniversaries pass without celebration as people try to express an embarrassment of emotions through double-pane glass. We provide decorated paper cups and napkins, flowers and crossword puzzles, and attempt fraught and challenging Zoom lessons. Servers and caregivers, strange bedfellows indeed, banded together on Valentine’s Day to write cards and deliver hard, chalky candies that read, “be mine.”

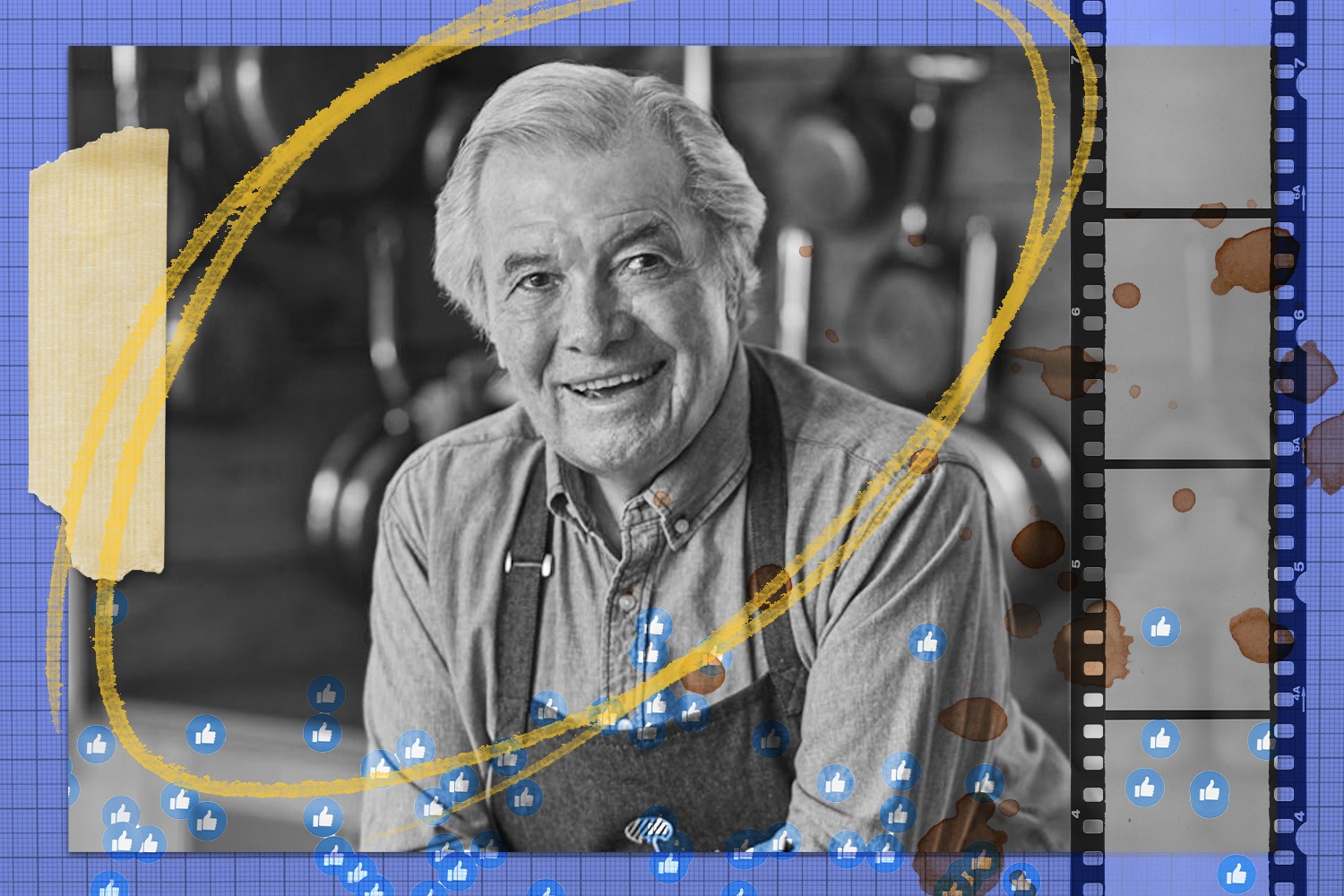

Dinner service at the Ballard Landmark in 2018.

Trisha Kostis

But everything we did was tinged with grief as we watched the physical and cognitive slippage of some of the people in our care. Those who faced challenges before COVID-19 struggled painfully after only a few months.

After 20 years of restaurant cooking, I made the leap to senior living in part because of the year I spent caring for my parents, both of whom had dementia. From the early days of my career as a baker, to “wo-manning” my own crew in a local café, I often wondered if my work might have a greater impact on those who seemed to need it most. If a simple fried egg sandwich could drag my father back from the murky tangles of Alzheimer’s for even a few minutes, certainly my classic lasagna and homemade sourdough could do the same for others.

During training for my first chef position in assisted living, the boss told me about the employee whose position I was to fill, considered by many not the greatest cook, but able to satiate the residents with her time and her attention. While it sounded a little folksy at the time, and the cynic in me wondered if the food would have been better had she spent less time chatting, I came to learn quickly that rapt attention from cooks, the chef, and servers goes further than an 8-ounce filet mignon, cooked perfectly medium rare.

After 20 years of restaurant cooking, I made the leap to senior living in part because of the year I spent caring for my parents, both of whom had dementia.

I am three years removed from front-line work, having accepted a promotion to corporate chef, where I am tasked with disguising healthy ingredients in familiar comfort foods, using crafty recipe modifications. Residents will eagerly eat succulent meatballs bound together with quinoa as long as we camouflage the superfood completely. But before this I spent ten years in kitchens and dining rooms explaining to exasperated seniors why we ran out of oatmeal and raisins, often the digestive infrastructure of their day. I felt personally responsible for the moldy strawberries that sometimes came in the with morning delivery and fully culpable when the highly anticipated evening dessert had to be changed from strawberry to blueberry shortcake. In every weathered and disappointed face, I could see my parents and grandparents.

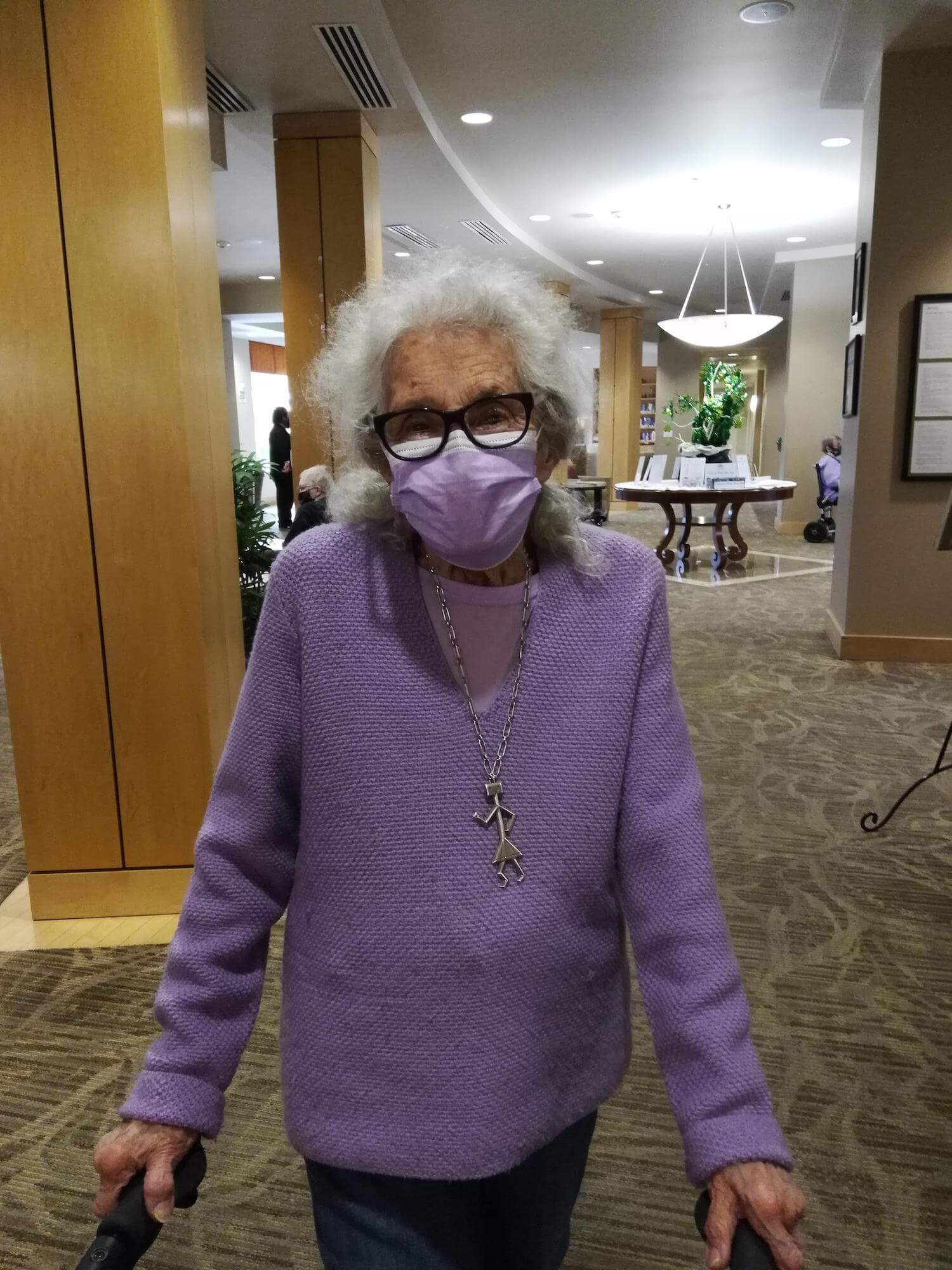

Before we had to shut down, I’d often stop in the communities, open my laptop, and hang out for a few hours, because visiting with staff and residents has always been the surest way to remain tethered to the reality of what we do. Absent that contact, I have to rely on reports from my experienced cooks. Chef Scott reported that Henny, our 91-year-old “lady in purple,” was still full of piss and vinegar about the lack of variety in our menu choices, a charge she has been leveling for five years. I used to challenge her whenever she cornered me in a hallway: what options could we possibly provide someone who was gluten free, pescatarian, and sugar averse, while still allowing for the preferences of the other 149 residents? Henny would reply, “steamed salmon and a sweet potato,” a dish about as popular with residents as Geoduck. But I could not refuse such a humble request and put it on our alternate menu, tempted to name it after her.

Trisha Kostis

Henny Phillips waiting in line for her second vaccine dose.

The first vaccine clinics started at the Ballard Landmark in the third week of January 2021. The following week, the Washington Department of Health released its Safe Start for Long Term Care, providing guidelines on how we could begin to finally return our communities to a version of normalcy. This allowed us to open the dining room a few weeks ago, which we announced in our weekly info-gram, the news spreading throughout the community like wild spring daisies. Even at 25 percent capacity, this hopeful step forward provided our forlorn residents the socialization they needed.

They understand the uncertain nature of this virus and that, in the event of another outbreak, we may be forced to box up delicate salmon dinners and fast-melting ice cream. They realize that they may not see their friends for another block of time – a terrifying thought when you are 91. But for now, the celebratory mood simmers under the fear just enough to make us all forget about what may or may not happen.

During our second vaccine clinic, Henny stood behind me in line, her purple mask set securely on the bridge of her nose, her pluck, to me, a familiar attribute of her generation. She poked at me with her cane, and it was difficult not to reach out and touch her, as I had so many times before. She was effervescent, her thick white hair standing out like a Fourth of July sparkler, dark eyes behind her thick glasses. This was the greatest day of her life, she told me, so nonchalantly that I was compelled to ask her why. Leaning closer, she reached out her knotted arthritic hands and set them on my shoulder, and I purposely violated the six-foot rule so I could hear what she had to say.

Vaccine day was the greatest day of her long life, she said, because now she could start living again.