Graphic by Tricia Vuong | Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images

The 1921 violence destroyed Black residents’ homes and a thriving food system built on community and entrepreneurship.

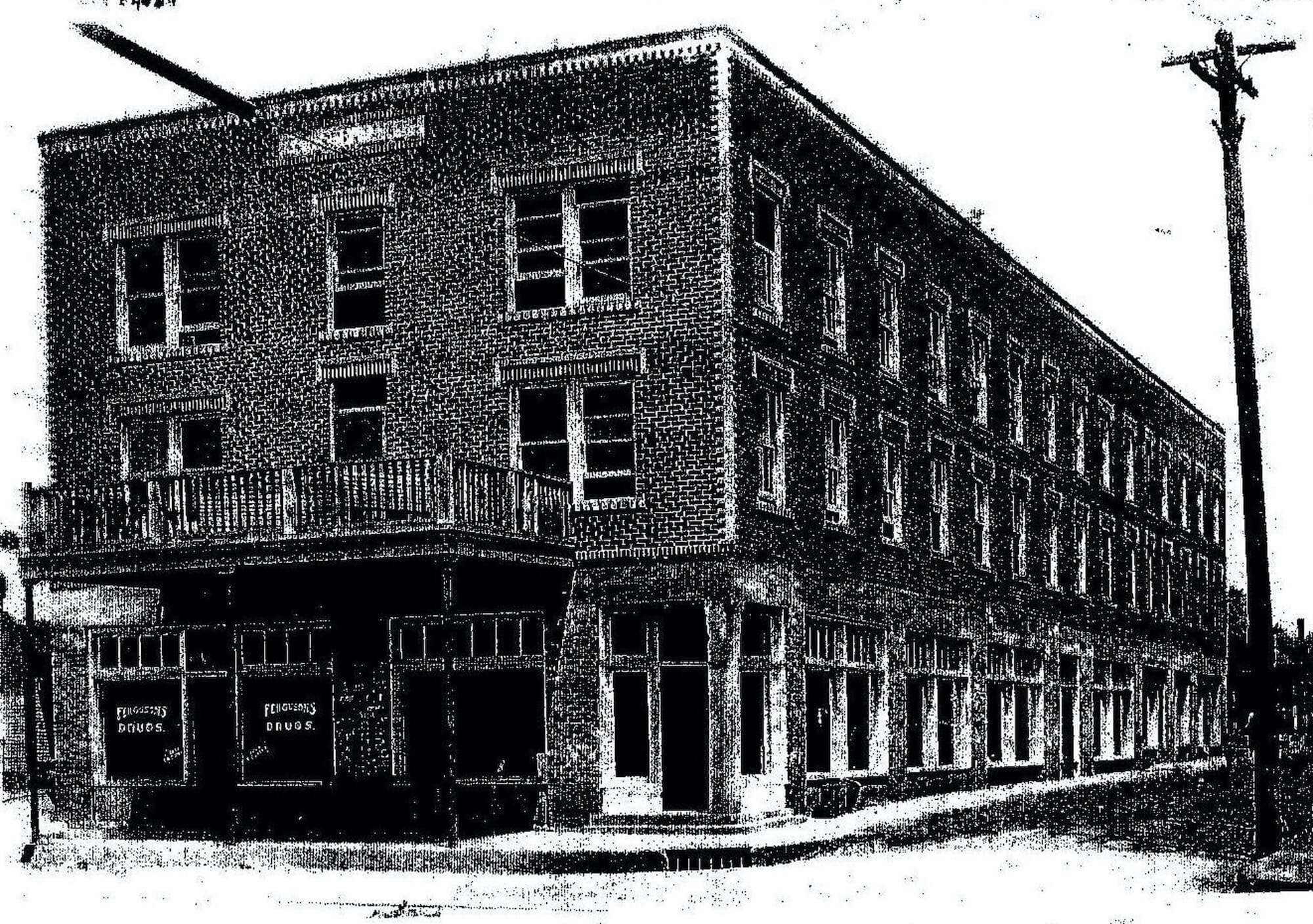

Pictured above: The Greenwood district, about 35 blocks of Black homes and businesses, functioned like a small bustling village within the larger city of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Pictured here, in this colorized image from sometime before 1920, it had two newspapers, scores of buildings, four hotels, and its own bus line. It was obliterated in the Tulsa race massacre, which happened 100 years ago on May 31 and June 1, 1921. Estimates vary about how many people died—perhaps as many as 300—but the city is still researching and uncovering mass graves.

When O.W. Gurley bought a stretch of land close to downtown in north Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1905, he opened People’s Grocery Store and a rooming house near the railroad tracks.

Black Tulsans found both opportunity and opposition in the majority-Black commercial and residential area that became known as the Greenwood district. Food and hospitality businesses were at the center of Greenwood—and Black grocers and hoteliers at the heart of its politics—at a time Oklahoma’s first law as a state ushered in segregation in transportation, housing, and anything potentially involving “race mixing,” especially marriage law. And those businesses were wiped out in the Tulsa massacre 100 years ago on May 31 and June 1, 1921, in which white vigilantes literally burned Greenwood to the ground.

Gurley’s businesses had served Black migrants who had been trekking into Indian Territory in increasing numbers since after the Civil War (Oklahoma wouldn’t become a state until 1907). The city’s African-American population multiplied five times between the 1910 and 1920 censuses. Most of the newcomers settled in Greenwood, which whites pejoratively called “Little Africa.” In the heart of the Plains, these “Exodusters” were looking for jobs in oil and mining; land ownership; and, for native Southerners, the hope of more freedom than their home region had afforded them.

Among the first Black businesses founded in Greenwood, Gurley’s rooming house and grocery anchored the bustling district Booker T. Washington once called the “Negro Wall Street.” The district’s Black grocers, innkeepers, and restaurateurs—Gurley filled all of these roles and more—offered food, lodging, and safety in numbers to Black residents and travelers barred from patronizing public accommodations in white sections. Gurley and Tulsa’s growing list of other Black grocers, restaurateurs, and hospitality workers knew they needed to know the people to prosper, something that was easy if you were the one selling them food, giving them credit, and listening to their good and bad news.

The Stradford Hotel, which had more than 50 rooms and luxury amenities, opened on June 1, 1918. Three years to the day it opened, it was reduced to ashes by fires set during the massacre in the area known as Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street.”

Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images

By 1920, there were plenty of places to stay, eat, and drink throughout the district’s 35 blocks. Lawyer John the Baptist (J.B.) Stradford had arrived in town after graduating from law school in 1906, and like his sometimes-partner Gurley, he knew how to turn a dollar.

On June 1, 1918, he opened the Stradford Hotel at 301 N. Greenwood Ave. It was one of the few Black-owned luxury hotels in the United States. It featured a dining hall, café, a gambling room, a saloon, and a large event hall—not to mention 54 suites; the property was valued at more than $2.5 million in today’s dollars. The hotel was the place to stay if traveling while Black in Tulsa; four other hotels were operating in Greenwood at the same time but none as opulent as The Stradford.

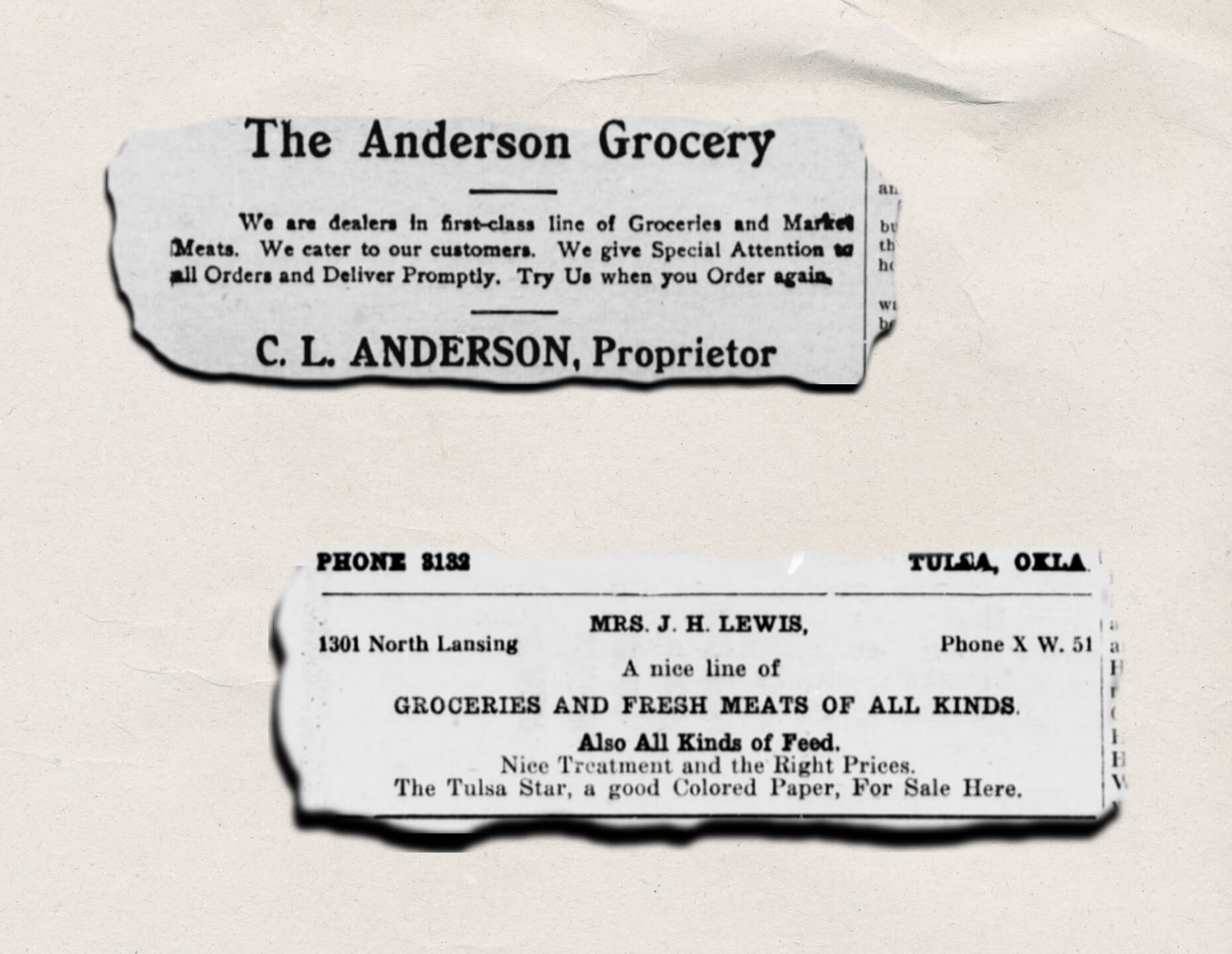

By design, Greenwood was a destination for Black people traveling to and throughout the West, offering food options that ranged from catering, home-cooked meals, and groceries for train travelers rolling through. Markets and eating places lined streets, and residents made money as owners, laborers, and cottage-food producers. From 1919 to 1921, the Tulsa Star, one of Greenwood’s two newspapers, ran ads for the following market proprietors: C.L. Anderson, P.M. Smith, the Williamses, Henderson Brothers, E.L. Lewis, Arthur Bell, and others.

A Mrs. Josie Daniels sold home-cooked meals direct to customers and wholesale. A fish market peddled local catch and shellfish commercially and to the public. There were barbecue restaurants, chili parlors, juke joints, butchers, drug and sundry stores, confectionaries, ice cream shops, and bakeries. Stradford, Gurley, and other enterprising business people had created a community with a sustainable, highly functioning food system.

It was destroyed over two terrible days in 1921.

The Tulsa Star, a Black newspaper serving Greenwood, routinely ran ads for Black groceries and food businesses. Here, the Anderson Grocery promised prompt delivery in a 1914 ad. Six years later, Mrs. J.H. Lewis promoted “fresh meats of all kinds” along with “nice treatment and the right prices.”

The Tulsa Star

On the night of May 31, 1921, a mob of angry white men crowded around the Tulsa city courthouse in response to a call to lynch Dick Rowland. The young Black man was suspected of sexually assaulting a white female elevator operator, Sarah Page, on May 30, Decoration Day (the precursor to Memorial Day). Stories vary, but some say Rowland simply fell into the girl when the elevator lurched and she screamed. During the heyday of lynching, that scream was justification enough to set off rape rumors. White men quickly mobilized to “avenge her honor,” though she confirmed nothing happened.

A group of armed Black Greenwood men walked to the courthouse with grocer O.B. Mann to protect Rowland from the growing mob. Mann and his two brothers, McKinley Monroe and J.D., had opened a market in 1919 at 1502 N. Lansing Ave. In total, the family owned three grocery stores in Greenwood.

The very community that prided itself on self-sufficiency was now eating handouts, a punishment for the sins of those who stole from them and ravaged one of the nation’s most vibrant Black communities.

The most common story, which has been retold fuzzily like through a game of telephone, has a confrontational white man attempting to take a gun away from someone who may or may not have been Mann, a Texas-born World War I veteran. Whoever that Black man was, he resisted. And a shot was fired. After a mob of white men looted area businesses for guns and ammunition, the sheriff deputized dozens of white men, giving them permission to shoot in the name of law and order.

By dawn on June 1, the assault on Greenwood was in full effect. The businesses on Greenwood Avenue were among the first casualties; the lavish Stradford Hotel burned to the ground. Gurley—once a “colored” deputy who had law enforcement and business dealings with whites—watched mutely as the mob ejected guests from his hotel and its restaurant. The marauders moved quickly. O.B. Mann’s grocery store was damaged. McKinley’s emerged untouched. But brother J.D.’s Greenwood store was destroyed.

On the left, an image shows what the Greenwood district looked like before mobs of white men burned it to the ground on May 31 and June 1, 1921. On the right, an aerial view of the ruins after the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Image | Library of CongressWhite vigilantes soon looted and set homes on fire. The conflagration consumed 1,200 homes and almost every structure in the district. As Buck Colbert Franklin, a lawyer and father of the late historian John Hope Franklin put it in an eyewitness account discovered in 2016, “The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. … I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half-dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?’”

Within hours, bodies were on the street and, survivors said, floating in the nearby Arkansas River. A 2001 report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 noted the wildly different estimates of people killed: as low as 18, a longstanding number of 37 who could be identified, and as high as 300.

“I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half-dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?’”

—Buck Colbert Franklin, lawyer and father of late historian John Hope Franklin

White deputies corralled Black residents into the streets and marched them to three detention camps, including one at the local fairgrounds. They were treated as prisoners of war, amid allegations that Black militant groups or armed organizing provoked the carnage. Within weeks, a grand jury proceeding declared, “There was no mob spirit among the whites, no talk of lynching, and no arms. The assembly was quiet until the arrival of the armed Negros, which precipitated and was the direct cause of the entire affair.”

Survivor testimonies documented for the Tulsa Race Riot Commission describe the dull and monotonous diet in the camps: bread and milk for children, apples, hot dogs, or biscuits. Mothers and fathers could not provide food for their families. Children waited in line for rations. The very community that prided itself on self-sufficiency was now eating handouts, a punishment for the sins of those who stole from them and ravaged one of the nation’s most vibrant Black communities.

More than 1,200 Black-owned homes were destroyed in the 1921 violence, many of them looted beforehand. The attack sent Black Tulsans fleeing for their lives, like this unidentified woman who clung to a truck stuffed with belongings during the massacre. Many Greenwood residents left the city, never to return. But thousands were in detention camps they couldn’t leave without a white person’s vouching for them. When the camps closed, many lived in tents provided by the Red Cross.

A 1921 post-massacre report from the Tulsa World mentioned that those with nowhere to go “were required to pay for their meals, either out of their own pockets or by working at various tasks, including cleaning up the debris in Greenwood. For this, they were paid standard laborers’ wages. It was by no means an easy existence, but some whites soon complained that blacks were being ‘spoiled’ at the fairgrounds and by the attention given them by the Red Cross and other charitable organizations.” Once in the camp, Black Tulsans couldn’t leave without a white employer vouching for them—often so they could come and work as domestics. When they did leave the camps, they were required to wear green identification tags. Less than a week after the massacre, 7,500 such tags had been issued.

The Red Cross’ assistant field manager, Maurice Willows, arrived in Tulsa from St. Louis on June 4 to meet grieving, fearful, and undernourished Black Tulsans. He immediately requested that the city declare the crime scene a “natural” disaster. That way, the organization could assist without too many bureaucratic complications. But it also ultimately contributed to the fiction that the massacre was a riot or something other than a carnival of white-engineered violence. Mayor T.D. Evans complied.

“The mom-and-pop shops of North Tulsa were replaced by grocery chains that were better equipped to compete with Walmart. But they, too, eventually folded. The Albertsons store turned off the lights in 2007.”

—Victor Luckerson, journalist

Evans also worked overtime to thwart survivor efforts to rebuild. He refused outside financial assistance for survivors. Black churches, NAACP chapters, and civic organizations sent in offerings—a few dollars here, a few dollars there—to fund the relief. Within a short time, the Tulsa Public Welfare Commission passed a new ordinance mandating that fireproof materials be used in residential neighborhoods, making it too expensive to rebuild.

Buck Franklin and other lawyers in the district successfully blocked the ordinance, clearing those rebuilding to use wood for shelter in preparation for a cold Oklahoma winter. Rented housing at the former detention centers was over by June’s end. Many residents were forced to fend for themselves in tent cities constructed on the site of burned-down buildings. Some built shotgun shacks and small houses with wood supplied by the Red Cross and magnanimous lumberyard owners.

But rebuilding never happened for much of Black Tulsa. Once millionaires by the standards of their times, Gurley and Stradford were indicted for “inciting a riot” and escaped the area as fugitives who were exonerated after their deaths. O.B. Mann also fled similar charges. A common insurance policy clause—refusing payouts in cases of “rioting”—meant that no Black property owners were compensated for their material losses, and more than 150 civil lawsuits (some blaming the city of Tulsa for inaction or its agents for fomenting or participating in the violence) went nowhere.

After the Mann brothers lost one of their three family-owned groceries in the 1921 violence, they rebuilt and reopened. This image shows their popular grocery and market at Lansing Avenue and Oklahoma Street in Tulsa, circa 1940s.

Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images

Three weeks after the massacre, O.B. Mann’s brother, McKinley, reopened one of the family’s three groceries. O.B. would eventually come back to rebuild the very successful Mann’s Luncheonette and Mann Brothers Market. But that would only happen 14 years later, in 1935.

Just four years after Greenwood burned, a full-throated effort to rehabilitate Tulsa’s reputation appeared in the Urban League’s Opportunity magazine. It described the Greenwood man who rented airplanes to oil tycoons, “one orange juice booth where delicious juice is served by an attractive colored girl in uniform,” and another businessman who commissioned 200 chickens cooked—but never eaten—for a convention (not only was Black Tulsa “back,” it could apparently waste wantonly). “Tulsa is ashamed of the riot,” wrote well-known Black business booster Albon Holsey. “Everyone apologizes for it and feels very keenly the fact that Negroes outside the state seem reluctant to come there.”

Greenwood’s food sector of restaurants, small grocers, caterers, hotels, and sundry stores never regained the luster of the pre-massacre days, even as the district attracted jazz performers and travelers from the 1930s onward. Later, integration meant Black shoppers could explore new stores without Jim Crow indignities.

By 2019, journalist Victor Luckerson wrote how Greenwood had “nine dollar stores and not a single high-quality grocer.” He added: “The mom-and-pop shops of North Tulsa were replaced by grocery chains that were better equipped to compete with Walmart. But they, too, eventually folded. The Albertsons store turned off the lights in 2007.”

Just in time for the Greenwood Race Massacre Centennial, Oasis Fresh Market opened in the neighborhood on May 11. A project of the Tulsa Economic Development Corporation and partners, it is the first full-service grocery store in Greenwood since Albertsons closed.

The neighborhood that once supported dozens of Black food businesses is now a food desert where Black entrepreneurs say they are being edged out by skyrocketing real-estate prices and gentrification in the new Greenwood.