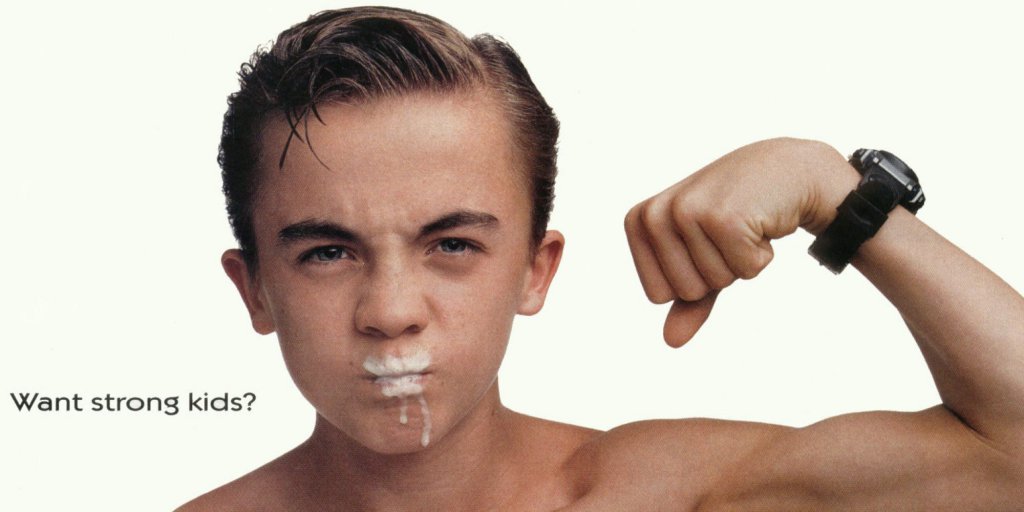

Sonoran Desert Falconry

Wildlife biologist Paula Rivadeneira knows feces can be funny. Informally known as Paula the Poop Doctor (@PaulaThePoopDr on Twitter), she’s no stranger to the poop-based pun. Her SCATT lab—that’s Super Cool Agricultural Testing and Teaching lab to you—is a mobile research center inside a bus-sized RV, one she uses in Arizona’s crop fields to makes scat (animal droppings) scat (go away). But she also knows when poop stops being funny: if it gets into the food supply.

No one wants to talk about it, but poop is a major problem in agriculture. And not just livestock poop. Many wild animals carry dangerous bacteria in their guts, and their feces—if it gets into feed troughs and crop fields—can make humans really sick. The stakes are high: Rodent and wild bird feces can lead to outbreaks of dangerous foodborne illnesses, including salmonella, E .coli, listeria, and campylobacter, in the human population.

Which is where Rivadeneira comes in. As a specialist for the University of Arizona’s cooperative extension, it’s her job to find new ways to keep crop fields safely poop-free. Recently, she’s been at the forefront of a surprising new food safety initiative, one that—somewhat counterintuitively—entails bringing more birds onto agricultural lands. Rather than barricade, poison, or blast interlopers away, she’s helping farmers police their fields with the aid of an unusual ally: trained falcons.

~

Yuma County, Arizona occupies an out-of-the-way corner of the Southwestern United States, bordered by Mexico to the south and California to the north. The county seat, Yuma, is a smallish city of nearly 100,000, known best for the historic prison that gives the local high school’s teams—the Yuma Criminals—their name. The surrounding land, meanwhile, is famous for two things: sunshine and agriculture. Known as both “the sunniest place on earth” and “America’s winter vegetable capital,” Yuma County sees 350 days of sun a year, allowing for about 230,000 acres of perennially-planted cropland. Though you can find melons, dates, and broccoli growing locally, along with more than 150 other crops, it’s primarily a lettuce powerhouse—with an acre of romaine or iceberg for every soul in Yuma. Ninety percent of America’s winter lettuce grows under these broad, blue skies.

Naomi Tomky

Naomi Tomky Yuma County is a treasure trove of nutrients, the lifeblood of salad chains, and a giant target for bird poop

Green lettuce grows in long rows, stretching through soil as richly brown as freshly ground coffee. The neat lines seem as if they could go on forever, if it weren’t for the Colorado River at one end, where the border begins. It’s a treasure trove of nutrients, the lifeblood of salad chains, and—with 100,000 acres just sitting there in the sun—a giant target for bird poop.

“Everyone knows: If you see poop, call me,” Rivadeneira says. Two to 3 percent of rodents and birds around Yuma, she’s found, carry foodborne pathogens of concern. “That seems low if you have only 10 rodents,” she says, “but high if you have a thousand birds land in your field.” Any poop in the field is risky and farmers treat any droppings they find as if they were contaminated with pathogens. Workers are trained to report animal tracks and scat immediately, Rivadeneira says. They can’t harvest anything within five feet of poop of any kind, according to food safety regulations, though some buyers voluntarily extend the quarantine to 50 or even 100 feet. “It’s too risky, you can’t just pick it and wash it,” Rivadeneira explains. “Water just pushes it around.” So, to prevent foodborne illnesses, she studies the poop and then she works to find ways to prevent the animals that left it.

Rivadeneira started asking Yuma’s farmers about feasibility, and most of their responses had to do with costs. It quickly became obvious there would be zero interest in a falcon-based solution that cost more than current methods. Fatima Corona, food safety director at JV Farms, a Yuma produce farm growing lettuce, broccoli, and other vegetables, said her boss had heard about falconry for abatement before, about seven years prior, only to decide it was expensive and required a lot of permits. But Rivadeneira had difficulty assessing just how expensive the method might be. Nobody had ever scientifically tested how many birds or what types were needed to cover how much area.

She put out calls and emails to every falconer she could find in California and Arizona. A few of the falconers called Rivadeneira back to say they couldn’t help, but many didn’t respond at all. “I was trying to talk to literally anyone,” she says. “I needed to explore with someone who understood falconry.” Only one person showed interest: Tiffany White, co-founder of Sonora Desert Falconry in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was a tangential detail in Rivadeneira’s email that first caught White’s attention: the way she’d mentioned introducing young minority children to falconry.

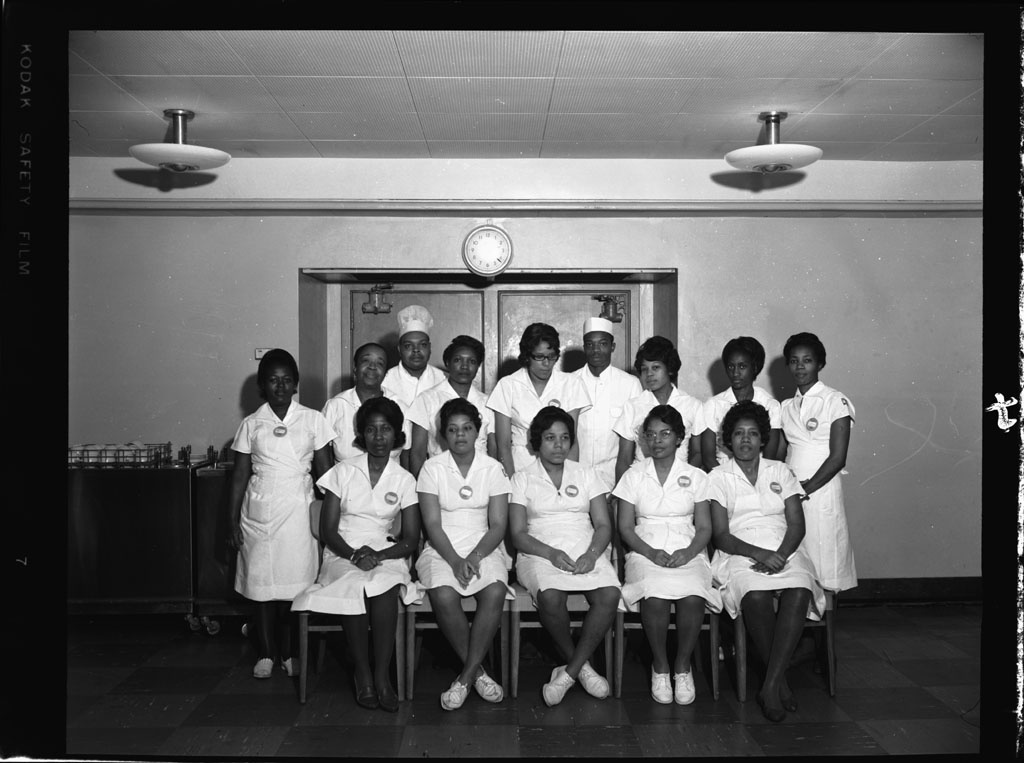

Sonoran Desert Falconry

Sonoran Desert Falconry Tiffany White, co-founder of Sonora Desert Falconry, had never worked with food crops or used birds for abatement in an agricultural setting. But she was excited about the potential implications of the work

“4-H groups, kids in local neighborhoods, tribal kids,” she recalls. “I just lit up.”

White started using her own wildlife biologist training to work in fisheries straight out of college. A co-worker of hers in Florida took her to a falconry meet, and it hooked her immediately. Within six months, she became the proud owner of a red-tailed hawk, with which she hunted, and one of only 30 African-American falconers to be certified nationwide. But falconry was only a hobby, if a passionate one, and she struggled to find a fitting vocation. She moved home to Michigan and sold mortgages. She moved to Arizona to work for Bear Stearns and got her MBA. She worked in marketing, strategizing pay-per-click advertising. Throughout, she continued her bird-based hobby.

Falconry turned into a full-time job by an unexpected turn of events: A tooth issue sent White, a self-avowed candy lover, in to see her dentist. She came out with a falconry apprentice—Sally Knight, the office manager. The pair plotted to start a women’s falconry club, which eventually became Sonoran Desert Falconry. It started in 2015 as a nonprofit focused on education, but eventually the women split out a sister company that does bird abatement, mostly for local resorts, restaurants, and golf courses (and whose profits support their non-profit arm). “Things just kind of evolved,” White marvels. “Now we have an office.” They also have a whole bunch of birds and even their own mini-food chain: In order to better feed their raptors, White and Knight now breed their own mice and rats.

Now, Rivadeneira has Sonora Desert Falconry to partner with on a two-year pilot, thanks to a $377,000 grant from the Center for Produce Safety, a California nonprofit. Right now, she and White are working to put together preliminary data showing that falconry works—scientifically and financially—for bird abatement, even on Yuma’s large-scale produce farms. Fatima Corona of JV Farms says that even if the project could reduce bird damage in the fields by 50 percent, it would be a huge advance.

If the project does take off, the women already know the end goal: An agriculture-oriented raptor center, ready to deploy falconers immediately as needed by the farmers. And to get enough falconers, they will go back to the original idea that drew in White: that the center would educate and train students, from underprivileged youth up through college, offering them a career option in agriculture beyond field worker or farmer. Right now, these dreams are high in the sky, but with every falcon that flies over Yuma, they get a little bit closer.