Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

A weekly series about one chef who closed three restaurants during the pandemic—and intends to get them back.

No one is unassailable in the restaurant business, but chef and restaurateur Gavin Kaysen comes close. The 40-year-old owner of three Minneapolis restaurants has had the kind of career young cooks dream of—at least the young cooks who take their work seriously. He’s been on the ascent since he became the executive chef at El Bizcocho, in San Diego, when he was 25. Three years later he won the 2008 James Beard Rising Star award, as executive chef at New York City’s famed Café Boulud.

Spoon and Stable, his first restaurant, opened in 2013 and was a finalist for the Beard award for best new restaurant. In 2017 he opened the bistro Bellecour, in nearby Wayzata, Minnesota, followed just over a year ago by Demi, a 20-seat tasting-menu space behind Spoon and Stable. In 2018 Kaysen won the Beard award for best chef in the Midwest region.

After 20 years in the restaurant business, Gavin Kaysen considered the future from a stable vantage point. He had started to talk about what he might do next.

And then everything collapsed, as Covid-19 cancelled daily life. Restaurants in major cities across the country now face an open-ended shutdown, and no one is immune, not places that booked prized tables a month in advance, like Kaysen’s, nor ones that barely clung to the dream that got them started. The only options are to close indefinitely or turn a restaurant into a take-out and delivery operation overnight, neither of which is sufficient to support the workforce. Between 5 and 7 million of the nation’s 15.3 million restaurant workers are expected to lose their jobs. The only reliable constant is bills—from landlords, purveyors, utility companies, linen suppliers, and more. It’s a long list.

But when President Trump got industry representatives on a conference call, they were all from big chains like McDonald’s and Domino’s. His definition of restaurant didn’t seem to include the independents who are most at risk. They would have to fend for themselves.

The impact of the closures stretches in many directions; for Kaysen, from the governor’s office to the duck farm where he buys birds raised to his specifications. He’s figuring out each next step in real time, as is anyone sitting atop a closed restaurant, trying to make the right decision on questions no one could have anticipated—without any sense of how or when this will end.

Kaysen has agreed to report on what he’s facing from now until his restaurants re-open, assuming that they do. The irony at the center of our initial conversation was more than painful: Just weeks ago, The Counter published my long look at the challenges restaurants faced in a normal world, before Covid-19. In retrospect, those familiar obstacles feel like the good old days; a struggle, yes, but a familiar one. At least restaurateurs knew what they were up against.

Our first call was on March 18, three days after the restaurants closed and two days before an estimated $100,000 in sales tax revenues was due. The following is the first chapter of Kaysen’s story, told in his words, condensed from that conversation.

—

Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The decision

For me it started on March 10, a Tuesday. We had some guests at Spoon and Stable, nurses and doctors, and when we were chatting they made me feel this was going to develop rapidly. My gut when I left that night was, ‘Whatever is in your mind, prepare for more than that.’

On Wednesday I kept talking it through with Alison Arth, our director of development. By Thursday it became apparent that no day was the same as the day before. By Friday, no hour the same. By Saturday, no 10 minutes the same.

What made it click completely was Sunday morning, around nine, I went for a walk with Andrew Zimmern, one of my best friends. We hadn’t seen each other for a while, so we walked, we had brunch, and then I went down to Spoon and Stable to see the general manager.

“That’s it. We’re closed.”

“How’re you doing?” I asked.

He said, “Chef, we’re starting to get a little scared about even being here.”

And right then I said, “That’s it. We’re closed.” I didn’t build a business to create fear, I built a business to create joy. I regret it got to that point at all, but I’m conscious that nobody knew it would get to that point that quickly.

I went over to my office, and I didn’t get home until midnight. I sat with Alison, wondering how do you figure out four months of lawyering in six hours? I never thought I’d have to do this.

How do we communicate to the staff that closing the restaurant is the single most considerate thing we can do for each other right now?

The number one question was how do we take care of the team, what does that look like, and then how do we communicate to the team and what does that look like? Forget the consumer side for a minute. We’ve closed before—we’ve all been through a shitty snowstorm and had to call customers to cancel reservations.

But how do we communicate to the staff that closing the restaurant is the single most considerate thing we can do for each other right now—and also have them feel we’re going to do as much as we can for as long as we can to take care of them?

—

Photos by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The announcement

Sunday night, March 15, we sent out an email to all the managers telling them we need to get on an immediate emergency phone call, has to happen no matter what, that was step one. At about 9 p.m. we had a conference call and told the management team about an email that was about to go out. We sent it to Annah, the executive assistant, to translate into Spanish for our employees who can’t read English perfectly, which took about 20 minutes.

And then we pressed “send.”

I recorded a video right before the call, but it took three tries for me to get through it. I’m an emotional person anyhow, but I can’t recall, since I was a kid, where I’ve gone through stages of the day when I feel powerful and others when I’m just weeping. I cried through the first two tries. When we were talking to management I started to weep, too, so Ali took the phone and then she broke down and I took it back. I joked with her: she couldn’t even last five seconds.

—

Photo by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The response

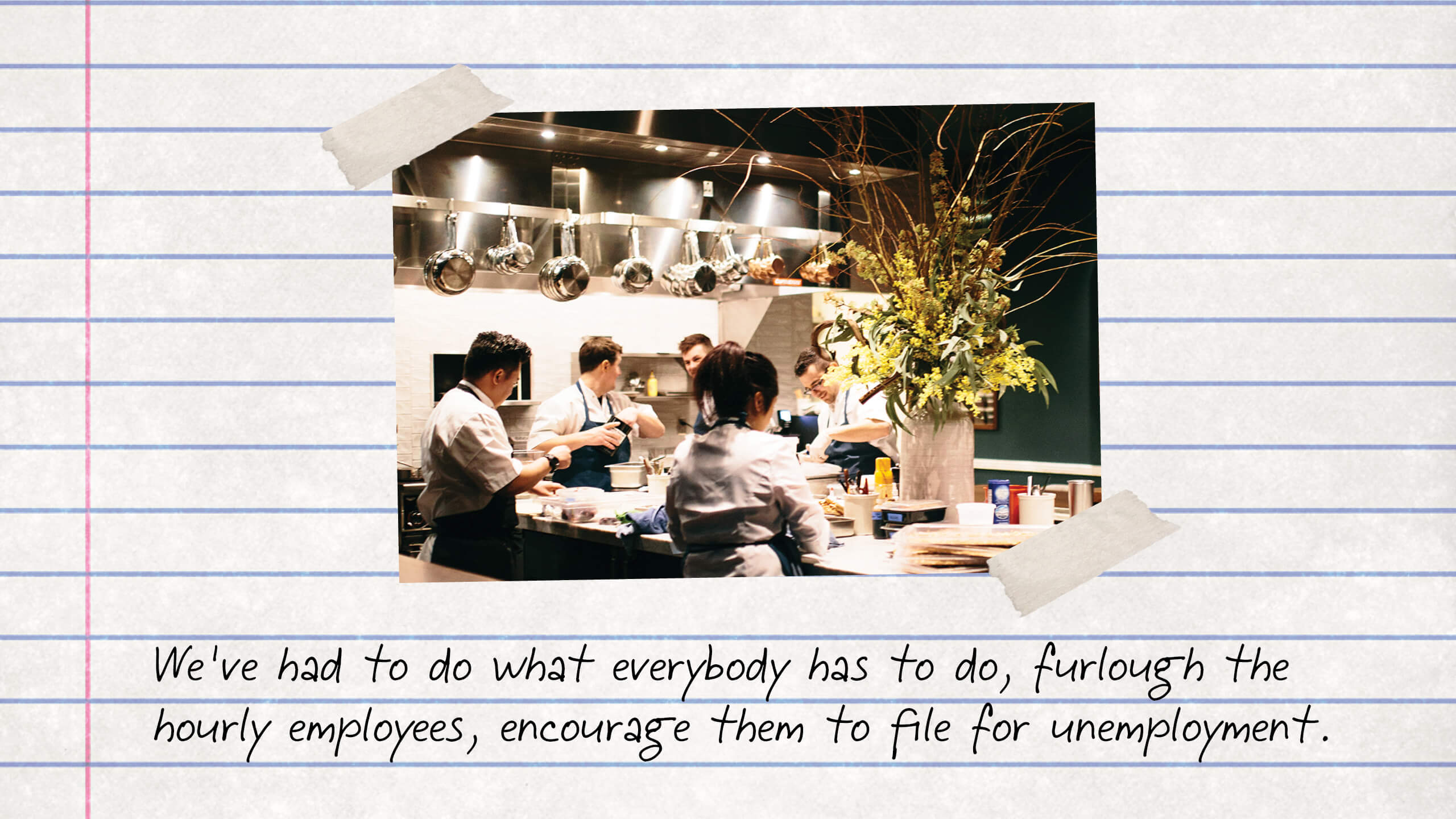

We’ve had to do what everybody has to do, furlough the hourly employees, encourage them to file for unemployment.

Someone said, you have to be prepared when you reopen; you’ll be paying a premium through the roof for unemployment, because we’re not contesting anyone’s claim. And any time an employee files for unemployment, and wins, the percentage we have to pay increases. But the governor, Tim Walz, came through on that, and said that the state is not going to increase any business’ percentage just because people are applying.

I’m not sleeping much lately. But what enables me to take a nap is that our whole team got paid on March 17, it was just the way our schedule worked out, right after the closing. Again, credit to the governor, who said they’re going to spit out the unemployment checks quickly. So people could get their first check next week.

We paid for their health insurance, 100 percent, until May 1. If this thing goes longer, if a month from now we’re still looking at this, and not up and running by May 1, then we have to make a decision—whether to pay that 100 percent health insurance for another month.

We’re working on figuring out what that number of people is. We just went through open enrollment for health insurance, so the number has probably changed in the last 15 days.

And there’s sales tax, that we pay monthly. We closed on March 15, and five days later we owed about $100,000.

And there’s sales tax, that we pay monthly. Every business is different, based on sales, but we closed on March 15, and five days later we owed about $100,000. I recognize that sales tax is a pass-through in our business—I tax the guest, I collect the tax and pass it through to the government. But I put up a petition and a post on change.org, to Governor Walz, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey and Senator Amy Klobuchar, asking, Can we turn that into a trust tax? I won’t not pay it, but can we defer it, take an abatement, to hold onto that tax in our accounts as long as possible?

State, local, federal? So far state and local have been the most responsive, and given me the most clarity. I wrote in the post that we were getting these tone-deaf emails that our taxes were due. And the mayor of Minneapolis, whom I’ve known since I opened Spoon and Stable, called to ask, Are you really? I said Jacob, we got an automated email at two o’clock yesterday saying don’t forget to pay these taxes. I understand it’s automated. I’m not fighting for the sales tax for me. I’m trying to build an alliance.

We found out on the 15th we had to close and the tax is due five days later? C’mon.

The amount will be much lower next month. Gift card revenue will be slightly increased, and there’s a sales tax on that, but the total will be significantly lower.

This is uncharted territory, and I didn’t want to put more weight on officials’ shoulders, but this was one quick immediate measure that could help. And Governor Walz and Mayor Frey listened and responded to our petition for relief. The governor announced that the deadline will move back a month with no penalty. I’m thankful to both of them.

—

Photos by Libby Anderson/Flickr/Nicolas Raymond/Graphic by Talia Moore

The next steps

I fall asleep due to exhaustion, but at 2:30 or three in the morning I’m up. People don’t understand what goes into building and running a restaurant.

We are all going to make mistakes right now. Everyone has to take a step back and say, We don’t know what to do. There has to be clarity in admitting that. We need to say, What do we need immediately, what do we need in two months? Some of this I’ve never thought about before. What do you do when you close all your restaurants?

For a while we’ve been going out to restaurants that we find “rate-able,” versus restorable. The current situation will push people to find more of that restoration, and connectivity, when they go out to eat again.

At Demi, we go into a story for the customers, about how the word “restaurant” comes from restoration, or to be restored. For a while lately, a lot of the time, we’ve been going out to restaurants that we find “rate-able,” versus restorable. I think the current situation will push people to find more of that restoration, and connectivity, when they go out to eat again.

That celebration, that freedom we all had a week ago, is probably going to create more emotion now that it’s gone than I can describe. It’s hard for people to comprehend that it’s gone, right now.