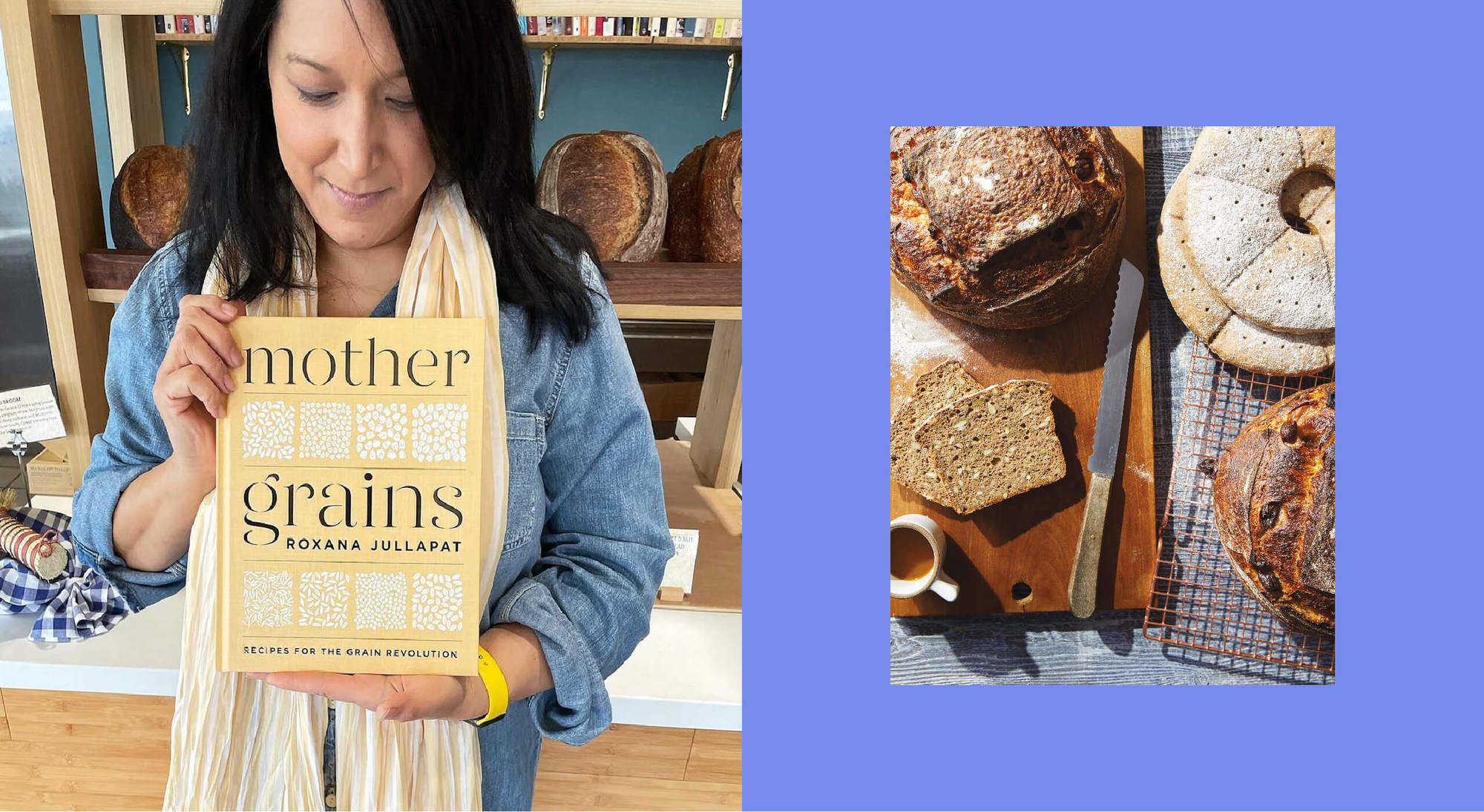

Photos by Kristin Teig | Graphic by The Counter

Think whole grains are “difficult” ingredients? Roxana Jullapat will set you straight.

Roxana Jullapat’s new cookbook, Mother Grains, is a hardcover dare: She defies the home baker to try whole grains and not get hooked. Everything we think about baking with them is wrong, as far as she’s concerned—and she stands ready to show the brave among us a better way.

More than ready. Jullapat is on a mission to upend preconceived notions about whole grains, most of them negative, having to do with the fact that each grain has a personality; you can’t simply swap them out for white flour or each other. The book, which focuses on eight domestically grown grains, is the result of two years’ research and testing as she and her husband, chef Daniel Mattern, prepared to open Friends & Family bakery and café. Since 2017, they’ve fed whole-grain desserts, breads, and savory dishes to the mash-up of neighborhoods that converge at her East Hollywood location.

She is a convergence herself, following grain traditions from Costa Rica, where she grew up, and her step-grandmother’s French and Spanish influences. The book reflects that. Mother Grains is a master class in global grain: babka with rye flour; blueberry muffins with spelt; sweet corn empanadas; and farro alla pilota, one of a handful of savory dishes.

Kristin Teig

Buckwheat fruit and nut bread featured in Mother Grains.

Previous zealots often sacrificed enjoyment in the name of purity (think of the throat-clogging desserts you encountered if you’re old enough to remember the 1970s’ natural food movement), or targeted a single ingredient for shaming, whether it was gluten, sugar, or dairy. Some of those campaigns changed the way we eat, though Jullapat raises a skeptical eyebrow about the value of the results: North America is the largest market for gluten-free bakery products in the world, far beyond the percentage of the population with a medical condition that requires abstinence. Jullapat considers that more a marketing coup than meaningful progress.

The third wave might well be the charm: Jullapat wants to insinuate grains into familiar recipes and let tasty nature take its course. “I want people to take this small risk with my recipes,” she said, “so that you learn to use this ingredient, learn to appreciate it. I want to lure you in.”

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

Like a politician reaching across the aisle, she’s prepared to work with the opposition to promote her agenda. The recipes use all-purpose flour and sugar alongside whole grains because it serves her purpose, which is to elevate the quality of whole-grain baked goods, make converts, and then ask them to do even more. She revamped a basic chocolate chip cookie eight ways, extolling the difference each grain makes in the final product, certain that bakers will find one they like better than the standard.

She doesn’t care that it’s an uphill battle, that most market shelves are still weighed down with bleached white all-purpose flour. She doesn’t care that quality whole grains cost more than commodity flour. The revolution has to start somewhere. And after just over 20 years in the pastry kitchen, she sees herself at the vanguard of a new movement, with nothing less than a whole-grain renaissance as the destination—for everybody.

“I like to root for the underdog, people, flour, everything. I’m not an award-winning chef,” she said. “I’m never on the list of nominees for this or that, so I don’t have to subject myself to certain norms of behavior. I want my bread to be an everyday thing, not ‘Here’s my precious bread, take a picture.’”

She’s not concerned if her intensity rankles people along the way. “I’ll pick a fight with whoever the hell I want, and in fact I do all the time. This book is because I’m trying to pick a fight. My goal is to show them, and sometimes I don’t even know who the ‘them’ is. It’s just the general ‘them.’”

Then she smiled, to take the edge off what she’s about to say, though not to sand it down altogether.

“What gets me up in the morning is spite.”

A pain d’amande, a filled almond cake featured in Mother Grains.

Kristin Teig

In that spirit, her rebuttal to our misconceptions:

I can’t bake: It’s too easy to fail, and there are too many rules.

Why would people be intimidated by any of this? That’s your first act of rebellion. People say things like ‘I could never bake.’ It’s a common commentary, this self-deprecating, self-defining commentary, but it’s more of a reflection of their personality and how they perceive themselves in the kitchen than of any reality. I’ve taught enough classes to know that there are some people who might not bake with ease, but I don’t think it’s beyond anyone.

I learned to bake as a child, very, very young, watching my mom, who’s a terrible cook and just an all-right baker. And I’ve trained staff for 20 years. I’ve seen people at all levels—with disabilities, difficulties, language barriers—learn how to bake. In my book, baking is not an impossible skill in any way. Quite the opposite.

And the thing about rules is, people don’t understand them. Once you do, it’s a knowledge gained. Rather than being oppressive or limiting, rules give you the freedom to concentrate on other things, because you have this knowledge of the dos and don’ts. And in baking, they aren’t arbitrary rules. They’re science-based rules.

Grains are too confusing. All-purpose flour is reliable.

I remember thinking that if I’m going to send a message, my voice has to be clear, loud, and eloquent. The message of grains has to be easy to narrate, and everybody should be able to say it.

I had a game plan based on the 20 x ’20 California Grain Campaign [created by a group of California farmers, millers, bakers and farmers markets] that started in 2016: By the year 2020, 20 percent of goods sold at participating farmers markets would be locally grown. If a vendor made bread, 20 percent of the product composition had to be whole grain. So I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to borrow this idea and say that by the year 2020 every baked good we make at Friends & Family will have at least 20 percent whole grain flour.’ That was a very achievable goal, I could articulate it, we put it on the website, all our staff knew.

Any time we formulated a recipe from ground zero, the first step was to think of the flour composition, do the math, estimate 20 percent. Not hard to do. And a lot of the recipes benefited from even higher percentages. So we have recipes that are at 20 percent and recipes that are 100 percent whole grain.

Some are really tough, like croissants, where we have played with higher percentages and then shied away. But to this day I’m surprised about the positive effects of whole grains. You might expect to have to compensate with more moisture or shorter baking times, but the rules don’t always apply from one flour to the next, one recipe to the text, which is what I’m figuring out. I made a sponge cake the other day that was 100 percent whole-grain flour. It’s fun to be surprised, after 20 years of doing this.

If you have someone who makes beautiful flour, makes it user-friendly, then the job is already half done. If you don’t, the mission could die in the field.

As for the recipes themselves, there’s an intuitive process to cooking and baking, in which you tend to put together things that grow together or look alike or come from a similar geographic region or culinary tradition. Bakers with a certain amount of mileage think similarly, and it’s very common to see bakers match dark grains with dark flavors such as brown sugar or chocolate, or assertive spices, like caraway with rye. I don’t want to say that I haven’t seen some of these flavor combinations before; rye and chocolate are not a rarity at all, brownies with rye flour, our rye and chocolate babka.

But I need another brain where I can put more new ideas. A lot of these recipes seem like epiphanies, like ‘Oh, how come I never thought of that before?’ And others, ‘I know there’s something there, but I need to explore it further.’

I’ve always put little bits of different flours here and there. If I made a cookie, I’d put corn flour in it because it has a nice grit. Nancy [Silverton, of La Brea Bakery and Campanile, where Jullapat worked from 2000 to 2002] used a bit of semolina here and there. And when I made crepes, I always put in some buckwheat. The bread I buy for my house has always been whole wheat.

I was on hiatus for two years before we opened Friends & Family in 2017, testing, doing home research, thinking of the bakery we would open; it was a time of curiosity. I baked with flours from everywhere, but when Nan Kohler opened her mill in Pasadena, Grist & Toll, the whole thing cracked open for me. She showed me the possibilities when you have really great grain and a robust grain economy. If you have someone who makes beautiful flour, makes it user-friendly, then the job is already half done. If you don’t, the mission could die in the field.

Hers made all the difference.

I already eat healthy baked goods. I love bran muffins.

I love a bran muffin. All through college, my breakfast was a big bran muffin I bought at the coffee shop on the corner, nothing special, probably full of sugar, wrapped in plastic. I really like that bran flavor.

But I realized that we don’t have recipes for bran muffins in this whole-grain renaissance—because bran muffins happen when you extract the bran from whole-grain flour and it becomes an ingredient itself. How can you re-create that without having to validate the misstep of removing bran? Because we don’t want to do that at all. I don’t want to send that message out there.

I just realized this, so I’m not there yet, in terms of a solution, but it happens all the time. Immediately my mind went to tons of orange zest and dried black currants. We’ll figure out the rest: I’d need to mill wheat coarsely so I can sift out larger pieces of bran, and then grind those myself to make them easier to use.

Gluten is the enemy. Sugar is the enemy. One ingredient is the enemy.

There was an obnoxious period of time in the mid-2000s when there was a lot of gluten-free stuff, a lot of quinoa and amaranth, a garbanzo bean flour kind of moment. Very healthy, very L.A., very Brooklyn. Very Gwyneth Paltrow, for lack of a better word. And people were focused on ‘no’: I’m doing an elimination diet, or I’m not doing sugar, or I’m not doing gluten.

It was huge; it still is huge. It’s very smart marketing because it sounds like an alternative culture of cooking and caters to a specific group of people.

But bakeries have existed for a long time and have always fulfilled a role in society, like bars. Should everyone go to a bar every day and have a drink? No. Should people have a drink at 9 in the morning? No. There is a time and a place for things we consume at a bakery, too, just like at a bar. Nothing good is going to come from bakers vilifying one type of food: When we attach adjectives such as ‘healthy’ or ‘nutritious’ or ‘high-fiber,’ we put ourselves in a niche before we’ve baked a thing.

Jullapat sees there is a time and a place for the things we consume at a bakery. She says adjectives like “healthy” or “nutritious” put us in a niche before we’ve baked them.

Kristin Teig

I brought all my experience to baking with whole grains, so these baked goods can still be completely decadent and delicious and worthy of a beautiful pastry case. And the reason is this: They are an alternative to all this talk of single things that are bad for us: Sugar is inflammatory, corn oil is subsidized. There’s more of a ‘calm down’ counterculture of having food closest to its purest form, and that’s my approach to baking.

How do you see a bakery in terms of health and nutrition? Pastries are not something to eat every day, but they’re something we can eat every week. Don’t have a croissant every day. I don’t have a pastry every day. Many times, I’ll have a slice of bread with butter or peanut butter. And then tomorrow, a cup of overnight oats. And then the next day, I might share a croissant with whoever is next to me.

There are plenty of baked goods in the repertoire of a grain-forward baker to create a balanced diet within a given period of time. Moments when you eat a little bit more, moments when you watch what you eat.

What’s the point? One person can’t make a difference.

People say that recycling is a distraction from the fact that we use a massive amount of plastic for the most superfluous of reasons, so true. The problem is the choice to use it, not the fact that we can recycle it.

And yet one can never ignore the power of a dollar. So the fact that an ever-growing group of consumers choose to abstain from buying commodity flour sends a message to the industry at large, that we are looking for better grain. That people who can are willing to pay a higher cost, that we understand the dynamics that make commodity flour less costly, like subsidies and corporate loopholes. And that we are aware of the consequences of industrial agriculture on the environment.

A trend like this also sends a message to smaller independent producers who realize, ‘Yes, I have an audience, I have a public.’ We’re telling them, ‘Yes, we like what you’re doing, please keep doing it.’

One can only hope that in making their operations more financially sustainable, we help reduce the cost of the flour. I want everyone who reads this freaking book to think that yes, buying better flour will make it more accessible to everyone.

We’re such a big country that we can’t seem to have a conversation that doesn’t involve a macro way of looking at things, whether it’s production or distribution. What if right now the price we are paying is just right? We have a skewed vision of the price of food. I don’t want to sound elitist; I’m a woman of the people. I want everybody to be able to eat better. And I feel it is an act of justice to buy better food for myself, because I’m educating myself and a group of bakers about using better foodstuffs, ones that are better for the environment. That affects all of us. I’m benefiting a farmer’s family and their workers. I’m acquiring knowledge and sharing it with others.

The goal is baking with 100 percent whole grain, which will require a couple of things. One is a steady supply of whole-grain flours, which is not the case right now. Even though the supply is good, it’s not consistent. The second thing will be a comfortable price point. And the third would be a good reception from the public, where you don’t have to explain that ‘Yes, this whole-grain croissant is not as tall as the other one—but it’s whole grain.’ If you have to explain the value of that to everybody, every single time, somebody is going to hit the wall, your staff, or yourself. But that is the goal. I think I will achieve it in my lifetime, and a lot of bakeries are doing it. I’m not alone.

In her bakery, Jullapat’s goal is to bake with 100 percent whole grain. A goal she hopes to achieve in her lifetime.

iStock/Marina Izvekova—

Even after 20 years, Jullapat is not yet ready to be the baker-owner who doesn’t bake, not yet, because the bakery is still too much fun, and her whole-grains crusade too urgent to step back. “I like to come in at 3 in the morning,” she said. “I enjoy my work, and I still take pride in being the strongest baker in the bakery. I identify with everything I make, and I like when I hear ‘It looks like Roxana made it,’ or ‘That looks like a Roxana recipe.’”

“I also love the group of people with whom I work—eight women, though I just hired a man because I don’t want to be labeled a man-hater, and we have a part-time employee who’s a guy. During the pandemic, we became tighter because we couldn’t socialize with anybody else. We got better; the recipes got better. And I was thinking that this is what happens to people who join a monastery, like the Tibetan monks. They become more monkish the more they are with other monks in their monastery. That’s what happened to us.”