Why avoiding uncomfortable conversations about equity, race, and access threatens to spoil a nascent movement’s environmental promise.

It hardly matters if you’re dealing with food justice activists or tech-startup entrepreneurs. Small, independent farmers or the corporate leadership of agribusiness giants. Policy wonks or research scientists. Everyone is talking about regenerative agriculture. Some even say it’s the future—and not just of farming. The most fervent advocates say so-called “regenerative” practices have the power to restore the balance between human beings and nature, a solution finally big enough to save our beleaguered planet from all of us.

Buoyed by the optimism of food producers, foundations, and corporate leaders, the term has gained new levels of visibility in the past two years. It’s spawned books by farmers and filmmakers, features in The New York Times and The Washington Post, and at least one full-length film—Kiss the Ground, a Netflix-distributed documentary. It’s become a marketing buzzword in the corporate world, too, with companies like McDonald’s, Target, Cargill, Danone, General Mills, and others pledging to use funds to support regenerative practices. The term has even been applied as a modifier to individual food products: In 2019, Applegate Farms, a subsidiary of major meatpacker Hormel Foods, debuted a line of “regenerative” sausages.

That private-sector momentum may soon get a public-sector boost. Advisers to President Joe Biden have suggested that the new administration launch a carbon bank for farmers as part of a plan to fight climate change, using the Commodity Credit Corporation—the same government war chest President Trump used to bail out mostly white, mostly wealthy farmers for income lost due to his trade war—to pay agricultural producers to sequester carbon in the soil.

It’s a promising idea. Advocates for regenerative farming argue that agricultural fields can help bury carbon deep under the ground, offsetting the disastrous climate effects of burning fossil fuels—and that potential promise is a central part of its appeal. Even members of the U.S. Senate, not lately known for their consensus-building abilities, have crossed party lines to get on board.

But the growing, still-incipient movement harbors a secret below its hopeful surface: No one really agrees on what “regenerative agriculture” means, or what it should accomplish, let alone how those benefits should be quantified. Significant disagreements remain—not only about practices like cover crops, or the feasibility of widespread carbon capture, but about market power and racial equity and land ownership. Even as “regenerative” gets increasingly hyped as a transformative solution, the fundamentals are still being negotiated.

A growing movement harbors a secret: No one really agrees on what “regenerative agriculture” should mean.

That lack of consensus is visible at the most basic level. In a new study published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, scholars from the University of Colorado, Boulder looked at how regenerative agriculture was defined across 229 academic journal articles and 25 practitioner websites. They found that only 51 percent of research articles that used the term supplied any sort of definition, while 84 percent of practitioner organizations did. Meanwhile, among the sources that did provide a definition, the details varied dramatically.

Many—but far from all—of the sources surveyed said that “regenerative” was about improving soil health, or sequestering carbon. For some, the term meant using no-till practices or planting cover crops. For others, it was about integrating livestock and crop production, or improving animal welfare practices. For still others, it was about improving human health, or food access, or food safety. Some said it was about supporting small-scale systems. Others said it was about improving the social and economic well-being of communities, regardless of farm size. Some said it was about increasing yields. Some said it was about increasing profit.

“The study came directly out of my teaching, in large part,” said Peter Newton, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, and the paper’s lead author. (Disclosure: I audited Newton’s graduate seminar on the environmental impacts of food production at CU Boulder as a 2019 Ted Scripps fellow.) “I noticed that a lot of students were getting very interested in regenerative agriculture—and, at the same time, I was seeing a lot written about regenerative agriculture in the popular media. But I was not finding any standard or common definition of what it was. In any two consecutive conversations, two different people might be making very different assumptions or inferences about what regenerative agriculture is.”

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

In interviews with more than two dozen academics, industry experts, farmers, and ag-world advocates, I encountered an even broader set of concerns. Topics ranged from the federal crop insurance program and genetic modification to the market dominance of multinational processors and land access for Native communities. For every person, the term “regenerative” called to mind an individual set of associations. Priorities often did not overlap, or even outright contradicted one another. Some even resisted the label entirely, preferring other not-quite-synonymous terms, including “regenerative land use,” “agroecology,” or “real organic.” Others resented the sudden use of a splashy new label to describe time-honored farming methods, approaches that some food producers have long embraced due to preference, tradition, or necessity.

“Black and Indigenous farmers have been practicing this form of agriculture without any specific title or performative acknowledgement for generations. This is the way I learned to farm from my grandparents.”

—Angela Dawson, founder, 40 Acres Cooperative

“Black and Indigenous farmers have been practicing this form of agriculture without any specific title or performative acknowledgement for generations,” said Angela Dawson, the Minnesota-based founder of the 40 Acre Cooperative, a national agricultural cooperative owned and operated by Black farmers, in an email. “This is the way I learned to farm from my grandparents.”

Not everyone agrees this lack of consensus is a problem, at least in the short term.

“For those that are outside the regenerative movement looking in, it all feels like it’s just a big cloud. There’s a lot going on, and there’s multiple conversations happening at the same time,” said Tina Owens, senior director of food and agriculture impact for multinational food products company Danone. “This is how a movement gets started: There are many voices that all coalesce into a couple of key notes that we all end up singing after everybody gets on the same page. But that process takes a few years.”

She has a point. It took organic farmers decades to coalesce around a single standard—one that’s still subject to some debate, even with the meaning of “organic” codified into U.S. law. In time, we’ll likely see some alignment about practices and benefits and science and data, though, as I discovered, the basic principles of methods and quantification are still up for debate.

But I also saw signs of a broader tension in my conversations—one that may not be so easily resolvable. There are those who feel that “regenerative” is something that can be layered on top of farming as it currently exists. Others disagree, arguing that our challenges require a more fundamental readjustment. In their view, farming’s recuperative potential will be limited until we rethink the basic assumptions that support U.S. agriculture, financing, and land use, while looking harder and more deeply at ourselves.

Make no mistake: In this, something crucial is being negotiated. The debate over what regenerative agriculture means, and who gets to decide, spills over into the issues we care most about. It touches on our changing relationship to science and technology, on access and antitrust reform, on workers’ rights and racial injustice, on conceptions of the natural world and our place in it. It’s a conversation that forces you to draw a bigger circle, only to realize that circle isn’t big enough.

The debate over what regenerative agriculture means, and who gets to decide, spills over into the issues we care most about.

Let’s say, at heart, everyone agrees on one thing: Regenerative agriculture means farming in a way that makes the whole world better. If that’s the case, maybe the most telling thing isn’t your attitude on cover cropping or rotational grazing. Maybe the most telling thing is how large you think the whole is, and who and what gets to benefit from inclusion in it.

So, what is regenerative agriculture?

Well, what do you think is broken? And what would getting better mean?

—

For decades, American farming has relied on monocultures—large areas of land planted with just one crop. That approach makes it easier to farm large areas with scant human labor, but tends to be resource-intensive and environmentally depleting.

Left, cornfields in Carroll County, Tennessee, after harvest.

For decades, mainstream American farming has been dominated by the monoculture. Most cropland—which takes up nearly 400 million acres in the U.S., more than a fifth of the 48 contiguous states—produces just one commodity at a time, with vast swaths of land devoted to a single species of commodity grain.

These are nearly abiotic spaces, crowded and yet mostly devoid of life. Fewer organisms survive in the soil, a casualty of the pesticides and herbicides sprayed to kill weeds and foraging bugs. Even beneficial species tend to suffer: Commercial honeybees, which are trucked by the hiveload to make up for the absence of naturally occurring pollinators, get sick from chemical applications and too much of the same plant pollen. The dominant crop pushes out nearly everything else, fed on a diet of synthetic fertilizer. Once harvested, these grains are mostly shipped all over the world to feed to livestock—which also tend to be raised in sterile, dedicated spaces, on fenced-out feedlots and inside windowless barns.

This approach reflects an agricultural system that’s organized according to a single crude principle: yield. On balance sheets and in economic data, in news articles and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports, yield—how much of a thing is produced per acre—towers above all else. We grow food like nothing matters except the output. So while our agriculture looks like it’s thriving on paper, it’s failing according to nearly every other measure—failing its workers, failing the planet that sustains it, failing the public it is trying to feed.

“Monocultures in intensive production systems don’t seem to be the way forward. They are just not doing it.”

—Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, University of California, Merced biogeochemist

At least in some respects, that mindset is starting to change. It’s not a new realization that soil is a living ecosystem, or that food—the plants and animals humans eat—inhabits a broader environmental and social context. But there is new willingness among those in the food and agriculture industry, a trillion-dollar sector in the U.S., to consider farming as something other than commodities to be extracted from the landscape. There’s a new willingness to consider that more holistic strategies may have value after all.

For farmers, this change of heart may be partly a matter of self-preservation. Fertile topsoil has disappeared from farms across the Midwest. Drought and erosion are epidemic. Badly degraded soil can’t absorb water and nutrients as well, and is more prone to flooding. Meanwhile, climate change continues to make weather more extreme and unpredictable. These cascading crises put agricultural producers in an increasingly tough position. “We’re essentially trying to make up for many years of fairly thoughtless practices,” Anna Cates, Minnesota’s state soil health specialist, recently told NPR.

“I think from both from a practice perspective and a policy perspective, everybody recognizes that if we’re going to keep demanding that farming systems produce the food we need, somehow we have to ensure the health of that system and figure out ways we can protect it,” said Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, who runs the Soil Biogeochemistry Lab at the University of California, Merced. “Clearly, monocultures in intensive production systems don’t seem to be the way forward. They are just not doing it.”

University of California, Merced biochemist Asmeret Asefaw Berhe is one of many prominent scientists excited by the regenerative potential of soils.

Still, she notes, individual farm-level impacts have limitations as a metric—we may also need to look more systemically.

Bret Hartman / TED

The good news is that the research is clear: The practices associated with the term “regenerative agriculture” can address many of the problems plaguing American food production.

When farmers stop plowing up their dirt and avoid disturbing soil whenever possible, a method called no-till farming, they can slow erosion and increase water absorption. Cover crops—the practice of growing additional, often non-commercial plant species alongside cash crops, or planting them in between seasons to cover soil through the winter—can reduce the need for fertilizer, improve soil moisture and fertility, and limit water pollution, while improving biodiversity. Then there’s the animals: Grazing ruminants can help control weeds and clear cover crops while fertilizing and improving the soil.

Many farmers are still reluctant to take on the added cost and complexity inherent to these methods. It changes the nature of the work, shifting the emphasis away from yield and toward the management of a functioning ecosystem. It means broadening the circle of concerns one has to care about. But while existing policy makes this transition difficult, if not impossible, the potential environmental benefits are so significant that we’d be wise to do whatever we can to encourage them. That’s not only because we should all want cleaner water and healthier, more productive soils. Taken together, these methods may even help to mitigate one of the largest collective challenges we face: the threat of global climate change.

Regenerative agriculture shifts the emphasis away from yield and toward the management of a functioning ecosystem.

As plants develop, they suck carbon dioxide from the air, using it to grow new tissues—roots, stems, and leaves. Some of that carbon is contained within the plant itself, as long as it’s alive. Plants also return additional carbon directly to the soil through their roots. When those roots are allowed to grow deeply—think of an old-growth forest, or a native prairie, planted with a thick mix of perennial grasses—it’s more likely those carbon stocks will remain stored beneath the earth’s surface. In the context of farming, though, plants are only a temporary and incomplete carbon storage solution. Crops are planted and torn up each year, so their roots never grow very deep. And whenever ground is tilled for planting, it enhances the rate of carbon loss in soil.

Yet it’s increasingly clear that traditional farming practices, ones that had been abandoned or ignored by mainstream American agribusiness until fairly recently, can come with significant climate advantages. Not tilling can help keep carbon safely sequestered underground. Cover crops suck more carbon out of the atmosphere, and their root systems—if allowed to grow over the winter, or year-round—add more carbon-rich biomass to soil. Livestock, meanwhile, can harvest cover crops without killing their roots, then return additional carbon from those plant tissues to the soil through their manure. The benefits here are potentially profound, and not just because carbon-rich soils tend to be more healthy and productive. The soil carbon pool is thought to be three times larger than the atmospheric carbon pool—by far a vast enough repository to solve our climate problem, at least in theory.

This should all be welcome news, and from the recent flurry of news stories about the promise of regenerative agriculture you might think there’s broad consensus about what to do next. Superficially, everyone agrees: We can make food production less harmful and more beneficial. Yet something fundamental is still in doubt. A second, parallel debate rages behind the facade of broad agreement—one about how the benefits of regenerative agriculture are quantified, and how we know what’s really better, and who gets to decide.

—

In the CU Boulder study, Newton and his colleagues argue that existing definitions of regenerative agriculture fall into three broad categories. The first type, which they call process-based definitions, focuses solely on things farmers can do: plant cover crops, reduce tillage, integrate livestock and so on. From this perspective, regenerative agriculture is about how you farm.

The second type, which they called outcomes-based definitions, focuses on measurable environmental achievements like the amount of carbon sequestered, or discernable improvements in water quality. This approach is more or less agnostic about practices: How one farms matters less than what one ultimately achieves.

Finally, the third type combines elements of both process-based and outcomes-based definitions, suggesting that both the what and the how matter.

These distinctions might seem minor, but they are far from neutral. Consider, for example, the nonprofit Regenerative Organic Alliance (ROA), a leading certifier of “regenerative” claims. According to ROA’s standard, only organic farmland can be deemed regenerative—the latter is an extension of the former. But for other prominent entities, including the food processing multinationals Cargill and General Mills, “regenerative” can refer to both organic and non-organic farmland.

Such in-the-weeds differences have profound implications. The organic standard bans the use of tools that are ubiquitous in conventional agriculture, including genetically modified (GM) crops. So can farmers plant GM seeds and still be called “regenerative”? A outcomes-based framework might say yes: If GM crops can facilitate desired benefits—by producing higher yields, conserving more water, or sequestering more carbon than their organic counterparts—they should be encouraged. But a process-based framework might say no—some advocates argue that the ethical issues brought up by genetic modification, including the patenting of life for profit by private corporations, are inherently antithetical to the regenerative ethos.

Controversy over specific agricultural tools is only one part of the debate. Larger and more fundamental questions still remain unsettled. Namely: When an entity says its approach to agriculture is “regenerative,” how do we know their farming really has the benefits associated with the term? Is adherence to certain practices enough, or do we need more concrete evidence? If practices are enough, which practices? If data are required, what data?

Agribusiness companies often define their progress in terms of the amount carbon sequestered. But those measurements often turn out to be rough estimates based on the adoption of practices.

These lines of inquiry are especially urgent as the Biden administration considers policy that would pay farmers for sequestering carbon on their fields. If we’re going to use taxpayer dollars to promote certain approaches to agriculture, or if we’re going to assign a dollar value to specific environmental benefits, we need to know we’re getting our money’s worth.

Yet on this front, things get murky quickly. In my reporting for this piece, I noticed that agribusiness companies often define their progress in terms of desired outcomes—a certain amount of carbon sequestered, say. But, upon closer inspection, I’d discover that those measurements were in fact rough estimates based on the adoption of practices. They aren’t necessarily borne out by on-the-ground data.

Take Cargill, for example. The company has pledged to “advance regenerative agriculture” on 10 million acres of farmland by 2030—an area nearly twice the size of New Jersey. When I asked a Cargill press spokesperson if the company would use practices or outcomes to determine whether it had reached that quota, I received a confusing response.

“At Cargill, we’re really focused on what is actionable versus the definition itself,” the spokesperson said in an email. “It’s really about impact—what farmers can do on their farm to generate outcomes that are beneficial to the farmer, community, and environment.”

Cornelia Li

At first glance, this response suggests that the company will focus on measurable benefits—it cares about “impact” and “generating outcomes.” And yet that impact also seems to be stated in terms of “what farmers can do on their farm.” In other words, practices.

In a phone call, I asked Ryan Sirolli, Cargill’s global row crop sustainability director, to clarify. He told me that the company’s efforts are focused on two broad categories: greenhouse gas reduction and water restoration. In both cases, the company has set ambitious, science-based targets that it’s working to address through on-the-ground changes at its facilities and on the farms it purchases from. But while progress on water quality is tracked using a variety of metrics, including farm-level weather sensors and smart sprinklers, the metrics for greenhouse gas reduction feel less fully formed. While Sirolli mentioned specific tools Cargill might use to track soil health and carbon sequestration in the future, he said that the focus for now was mostly on encouraging farmers to adopt specific practices like planting cover crops. Cargill can then estimate what benefits might be achieved based on what practices are put into use.

“I think if we’re putting on requirements that we have to have soil sampling and all of these things, well, it’s incredibly expensive [for farmers],” he said. “In the end, that is an artificial barrier—versus if we just get cover crops across more and more farms across the Midwest. We know that has a huge impact. Today we’re comfortable with being able to model that, knowing it’s not perfect.”

“It’s not 100 percent accurate, and no one’s going to say that. But on average, over time and space, it’s going to be correct.”

—Dan Ryan, CEO of CIBO, on his company’s carbon modeling tool

That approach might make sense when it comes to benefits like erosion, drought resistance, and water quality. In those cases, scientists agree that practices translate roughly into outcomes. But it’s potentially problematic when it comes to climate mitigation claims: As of now, there’s really no easy way to say that X practice always yields Y carbon benefit.

There is still widespread scientific debate about how much carbon agricultural lands can actually sequester in the soil. The potential carbon benefit can vary from region to region, farm to farm, even from parcel to parcel within a single farm. It can change based on soil composition. It can change based on the level of nitrogen available. Some studies suggest that agricultural lands max out their carbon sequestration potential over time. And even minimal tillage has the potential to undo all a farmer’s short-term carbon.

Given this uncertainty, the scientists I spoke to generally weren’t as comfortable modeling carbon sequestration as they were other benefits.

“It’s not that we don’t know how much carbon sequestration is going to occur because of different practices,” said Berhe, the UC Merced soil scientist. “It’s just that we can’t pin it down unless we measure every spot. If I measure every soil profile, I’ll tell you exactly how much carbon is in there. But whether I can use that information to project over a large area, that’s a slightly more complex issue—because of how inherently variable soils are.”

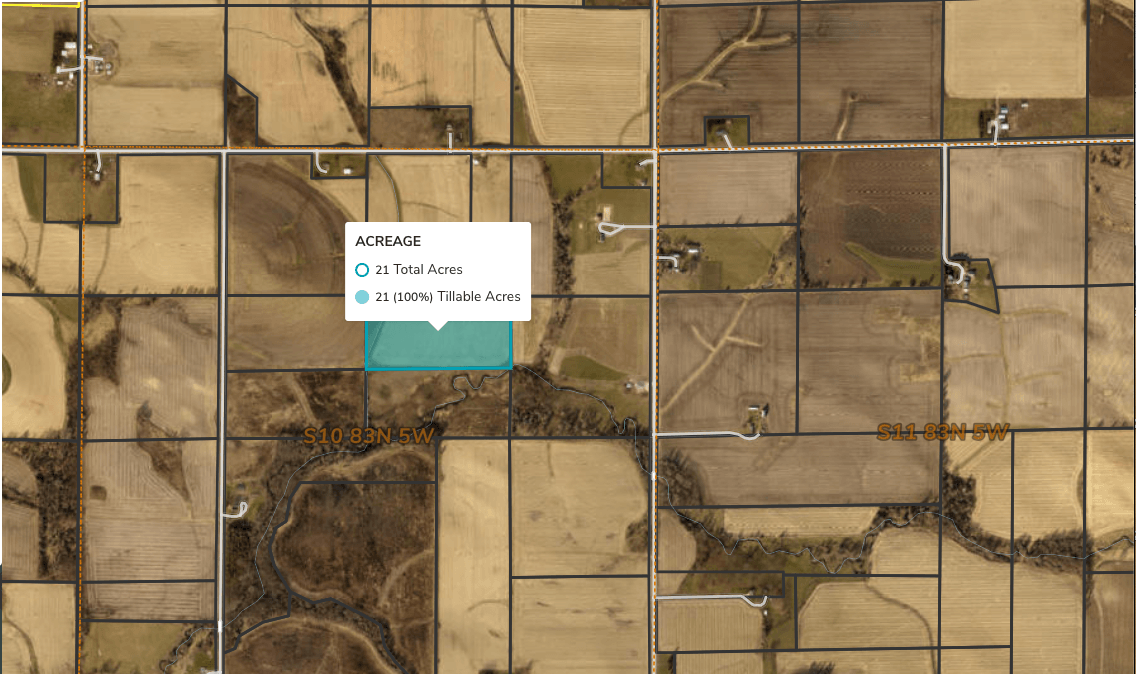

A tool developed by technology company CIBO has determined the “regenerative potential” of every parcel of farmland in the U.S.

Here, the tool has determined a 21-acre plot in Linn County, Iowa can offset about 27 tons of carbon dioxide emissions if regenerative practices are used.

CIBO

Modeling based on practices isn’t necessarily a crude tool. Dan Ryan is CEO of CIBO, a software platform that hopes to make it possible to verify regenerative practices at scale without on-the-ground testing. He told me that his platform has already determined what he calls “the regenerative potential” for every parcel of land in the U.S.—how much carbon could be stored under ideal circumstances, given the variety of factors present. From there, the platform uses satellite imaging to verify which practices are being used, while adding a layer of computer modeling that helps to calculate the overall benefit of these practices using data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and other sources. Though the models are validated against generic on-the-ground data over the years, direct measurements are not taken on a field-by-field basis—and Ryan thinks that’s just fine.

“It’s not 100 percent accurate, and no one’s going to say that,” he said. “But on average, over time and space, it’s going to be correct.”

Still, standards based on broad, well-meaning estimates can sometimes prove to be destructive. A recent article in MIT Technology Review shows how California’s “forest offset program,” which seeks to reduce carbon emissions by preserving trees, significantly overestimated the amount of carbon stored—allowing polluters to claim emissions reductions based their purchase of credits that had no real environmental benefit.

Berhe said a lot of the discussion boils down to how much uncertainty we can tolerate.

“Are we comfortable with, say, I don’t know, a 10 percent error? Or 20 percent? 30?” she said. “We have to be able to accept some error and variability—it’s inherent to this system. That’s okay from a scientific standpoint, maybe even okay from a farmer-trying-to-manage-their-land standpoint. But it’s quite problematic when you start to put dollar values with these measurements. That’s where the complexity gets into this discussion.”

If we’re going to develop functioning markets based on carbon sequestration, in other words, modeling based on practices may not be enough.

“We’re trying to build the system that can actually monitor what’s happening at large scale. No one has that ability to do that right now.”

—Debbie Reed, executive director of the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium

For Debbie Reed, executive director of the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium (ESMC), a nonprofit that’s developing protocols to measure the benefits of regenerative agriculture and is working toward the launch of a national marketplace for farmer-generated credits in 2022, on-the-ground carbon sampling is indispensable, if still impractical.

“We’re trying to build the system that can actually monitor what’s happening at large scale,” she said. “No one has that ability to do that right now.”

She said that collecting farmer- and rancher-specific data at field scale is “very rigorous” and “very expensive,” but ultimately worth the cost due to reduced uncertainty. I asked her to say more about why she’s so committed to on-the-ground carbon measurement, when some of the modeling approaches rely on such sophisticated tech.

“I think you have to,” she said. “If you look at USDA data, they have soil carbon databases like SSURGO. A lot of that data is 50 to 75 years old. We don’t really know what’s going on down there. We have so many instances where we actually test soil type and we see it’s not what’s in the database. It was created for a totally different purpose, and we’re now using it for a market context. If we really want to track what’s happening, we need better data.”

In a company blog post, CIBO lead data scientist Jason Route describes how the company uses USDA’s SSURGO database to help calculate its estimates of soil carbon impact—yet Reed says that data is decades old and potentially unreliable. It’s just one example of how competing entities still don’t agree on even basic fundamentals, even as farmers are already starting to generate income based on purported climate benefits.

The ability to measure environmental benefits is developing rapidly. But fixating on farm-level benefits can deflect from deeper, more systemic problems.

Yet these disagreements obscure a larger point. While entities like CIBO and the ESMC fixate on the best way to measure farm-level impact, others reject their premise entirely. These critics argue that analyzing farm-level benefits has limited usefulness when the broader landscape is still so fraught. The focus on the efforts of individual producers is a reluctance to think bigger, they say—a failure of imagination that limits the environmental potential of regenerative agriculture, while deflecting from deeper, more systemic problems.

—

Last year, the Netflix-distributed documentary Kiss the Ground started to bring the term “regenerative agriculture” to new audiences. With a swelling orchestral score, sweeping aerial footage, an A-list Hollywood narrator, and the backing of a company that’s arguably the biggest player in the movie business, the film makes no bones about its world-changing ambitions.

“This is the story of a simple solution, a way to heal our planet,” actor Woody Harrelson intones in the movie’s trailer, which has been viewed nearly 10 million times. “The solution is right under our feet—and it’s as old as dirt.”

The film’s entreaty is compelling because it’s so straightforward and direct: If the problems we face are complex and vast, the solution is the very opposite. That may be wishful thinking, but scientific oversimplification was not the main issue with Kiss the Ground. The film’s harshest critics say it failed to consider its own social context, reflecting aspects of the systemically racist culture that produced it.

The film has “frustrated and alienated a number of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in the food and agriculture world who say it all but excludes their voices and completely ignores their ancestors’ contributions to the regenerative movement,” wrote Gosia Wozniacka in Civil Eats. “What’s worse, they say, is that the film fails to step beyond its soil health focus and upbeat message about reversing climate change to address the social inequities and structural racism at the heart of American agriculture, including Black and Indigenous land dispossession, discrimination, and a lack of access to farmland.”

“The folks that are leading the ‘regenerative ag’ movement, the majority of them are either white men or they’re from university institutions.”

—A-dae Romero-Briones, director of Native agriculture and food systems at First Nations Development Institute

Ultimately, the nonprofit behind Kiss the Ground issued an apology for its presentation of the issues, and for the film’s overall lack of inclusivity. But the problem isn’t specific to Kiss the Ground. Sources for this story also expressed frustration that a large segment of the regenerative movement has focused so much on carbon credits—omitting the importance of addressing social and political issues as part of the regenerative ethos, while erasing the contributions of Native farmers and farmers of color.

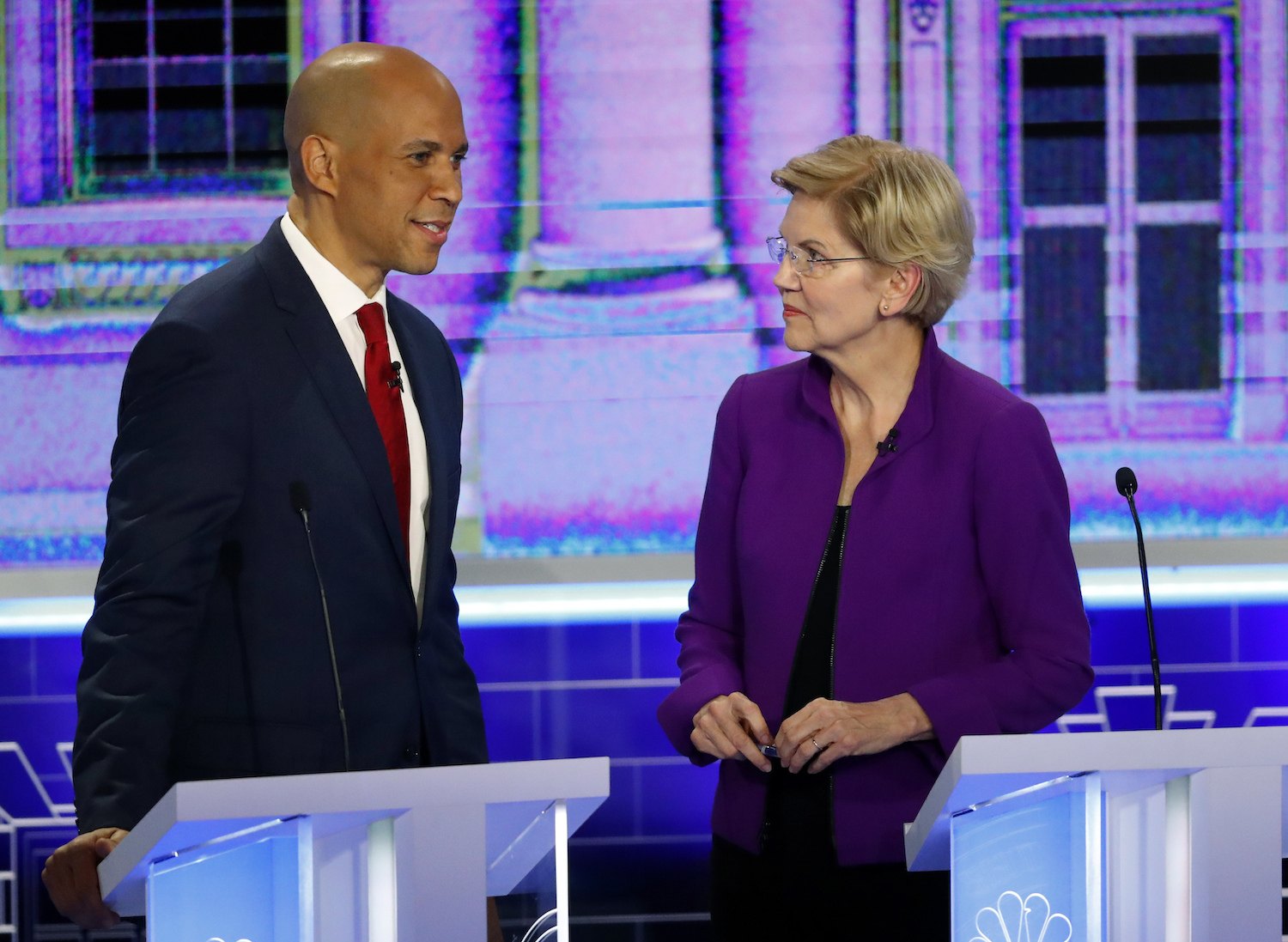

When I asked A-dae Romero-Briones, director of Native agriculture and food systems programs at the First Nations Development Institute (FNDI), a nonprofit working to improve economic conditions within Native American communities, she expressed disappointment in the disparate groups of people rushing to fix the planet under the banner of “regenerative.”

FNDI

A-dae Romero-Briones is director of Native agriculture and food systems at the First Nations Development Institute (FNDI).

“The folks in my social circle, my cultural circle, my professional circle, they’ve been to some of these conversations [about regenerative agriculture], but no one in any of my networks is ever leading them,” she said.

“I don’t have a lot of stake in this term,” she said. “The folks that are leading the ‘regenerative ag’ movement, the majority of them are either white men or they’re from university institutions. Both of these camps are far removed from the communities that I come from and work with. The folks in my social circle, my cultural circle, my professional circle, they’ve been to some of these conversations, but no one in any of my networks is ever leading them. When you’re not a central part of that conversation, it’s really hard to have a stake in the conversation.”

M. Jahi Chappell, a scholar and political ecologist who now serves as executive director of the Southeastern African-American Farmers Organic Network (SAAFON), was one of several sources who told me the process of defining “regenerative agriculture” had been largely led by prominent foundations, think tanks, and corporations.

“Regenerative agriculture has had a huge focus on marketing itself,” he said, “I just have a knee-jerk issue with the way it was sort of launched by thought leaders instead of a much more spread out, movement, consultative process.” The attitude, he said, has been, “‘We think it’s a good term. We’re all going to start using it now.’”

That approach, Chappell and others said, ignores other, parallel conversations that had been happening before “regenerative agriculture” hit the scene. He told me that “agroecology” is a term with a longer history, one that’s been defined through much more active conversation between scholars, activists, practitioners, and community stakeholders, as a recent academic paper co-authored by Chappell describes in detail.

But multiple sources felt that supporters of “regenerative” have largely ignored pre-existing agricultural, scientific, environmental, and socio-political frameworks, especially those developed by Native communities, Indigenous societies, agroecologists, and farmers of color. Instead, these sources said, conversations around regenerative agriculture often grew uncomfortable—even antagonistic—when issues related to power, access, compensation, and equity were raised.

Fatuma Emmad, co-founder and executive director of Frontline Farming—a Denver-based nonprofit that grows and distributes food, provides education and training, and advocates on a range of issues—interfaces with numerous white-led groups that are pushing for carbon credits and regenerative farming practices. She said the tone changes when conversations turn to improving farmworker protections, not just soil health.

“They’re fighting this bill so hard,” she said, speaking of a farmworker rights bill currently under consideration in the Colorado legislature. “It was really sad to see people I’ve worked across the table with for so long just disregard [their fellow] humans in this way.”

At the same time, there’s a perception that white farmers and agribusiness groups from Middle America are generally uninterested in the experience, knowledge, and priorities of those they perceive to be outsiders. Sanjay Rawal, a filmmaker who spent almost three years developing and shooting the film Gather—a documentary about Indigenous foodways financed by FNDI, which he describes as a movie created primarily for audiences in Indian Country—said such feelings are widespread in the communities he’s worked with.

“The Native scientists that I know, the Native agricultural professionals that I know, who have all the same certifications and qualifications as those with a seat at the table, see the people who are part of the system that created the problem now grasping for solutions,” he said. “While those who have always practiced the solutions, and who continue to practice the solutions, and who have really been at the spear tip of the exploitative institutions that damaged their society, now see those same institutions forming around these ‘modern’ principles.”

“It’s a little bit breathtaking to see that sort of arrogance at play,” he went on. “We who are non-Native came to North America and displaced a functioning system of agriculture and food production that had been here for 10,000 years. And within a matter of 250 years to 300 years, we’ve destroyed the value of the land. But those Indigenous practices are based on thousands of years of science. There’s plenty of genetic studies that show the incredible knowledge that it took to breed corn—when folks begin to study Native principles, they realize that they’re grounded in modern science. Yet these studies are done with very little participation from Native scientists.”

“When folks begin to study Native principles, they realize that they’re grounded in modern science. Yet these studies are done with very little participation from Native scientists.”

—Sanjay Rawal, director of Gather

Reed, the executive director of ESMC—one of the few ecosystems services entities that publicly acknowledges the importance of outreach to Black and Indigenous farmers—agreed that experts within underserved communities often go unheeded or ignored, with self-defeating results for the entities now scrambling to find ways to regenerate farmland.

“There’s a lot we don’t know,” she said. “And rather trying to figure out what it is, let’s go back to individuals and cultures that are, in fact, continuing to practice the way they have for a long time. We can learn a lot rather than reinventing the wheel there.”

“Indigenous people aren’t smarter or more spiritual than anybody else,” Romero-Briones said. “We’ve just had a lot more trial and error across a lot more generations. Now we’re at the point where we have all this experience and knowledge that has been passed on from generation to generation—when we talk about processes and outcomes, our timelines are hundreds of years. When people in regenerative agriculture talk about timelines, they’re talking about seasons.”

Opening doors and fostering dialogue always sounds great in theory. But if those racing to adopt—and profit from—“regenerative” practices stop to listen, they may not be prepared to embrace what they hear. That’s not only when it comes to issues that directly affect a farmer’s bottom line, like the minimum wage exemption. A more inclusive conversation may mean reconsidering aspects of the food system that many take for granted. It may mean entering uncomfortable, even unthinkable, terrain.

As buzz builds around regenerative farming, some argue that Native and Indigenous practitioners have not been properly recognized for their contributions to agricultural science.

Sammy Gensaw, a Yurok advocate, educator, and community organizer who appears in the film Gather knows that pain first-hand.

“The story of colonization seems to be the same,” he said. “They take what they like, and they put their own spin on it.”

Renan Ozturk / Gather

Consider, for instance, the regenerative movement’s sacred cow: cattle. The appealingly counterintuitive idea that “cows can save the planet” has taken on new currency of late, thanks in part to high-profile coverage in major media outlets and films like Kiss the Ground. Yes, when allowed to graze cover crops and perennial grasses in an actively managed way, cattle can help return carbon from digested plant matter to soil, which in turn helps increase biodiversity, water quality, and soil health across a variety of metrics. Great—now that that’s settled, we can all agree cattle are good. Right?

Well, no. Romero-Briones sees it differently: She points out that these benefits aren’t specific to cattle. Other species of ruminants can confer them, too.

“Elk are ruminants. Deer are ruminants. Buffalo are ruminants. These are all important protein sources for Indigenous people and always have been,” she said. “Cattle are in the same category, but the American diet and the American food system puts such an emphasis on cattle—to the detriment of all these other populations.”

“Cattle are in the same category, but the American diet and the American food system puts such an emphasis on cattle—to the detriment of all these other populations.”

As a 2019 article in the journal Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment put it, “In most of the world’s semi-arid and arid grasslands, the replacement of free-ranging wild herbivores with fenced-in livestock has caused degradation of vegetation and soils, resulting in declines in productivity and biodiversity, a reduction in ecosystem resilience, and overall decline in historic ecosystem services generated through the grazer/grassland relationships.”

If we know free-ranging ruminants are helpful, why not support systems that let them proliferate more freely? Wouldn’t that be consonant with the overarching ethos of regenerative agriculture, which is supposed to promote increased biodiversity and the integration of ruminants into cropland? You might argue that it’s easier to control domesticated species, or that infrastructure for processing elk and deer at scale does not presently exist, or that current regulations would make it difficult to sell their meat for human consumption. But the hangups aren’t just logistical. A closer look at the way federal lands are managed suggests a much more active hostility to these non-cattle species.

Romero-Briones brings up the example of the Point Reyes elk, or Tule elk, that have been reduced to a population of only 6,000 in California—and may be limited further under a controversial plan that would allow park service officials to cull them. Why? Because elk compete with cattle for grass, they’re seen as a nuisance by the ranchers who graze their livestock on the same federal lands the elk inhabit. It’s the same story in Yellowstone, where the remaining buffalo herds are contained and systematically culled when they grow in number—a plan that’s nominally about the threat of disease transmission but, as I’ve reported, is more likely about protecting ranchers’ monopoly on federal grazing rights.

Tule elk have been reduced to a population of only 6,000 in California—and may be limited further under a controversial plan that would allow park service officials to cull them.

Advocates of regenerative agriculture tend praise cattle while downplaying the ecological importance of other ruminants like elk, deer, and bison—animals that are still important food sources for Native communities.

Flickr/Tim Proffitt-White

Once you start to ask the question of why these ruminants, why cows above all, there are no easy answers. You can’t really argue that cattle have magical properties other multi-stomached herbivores lack. You can’t really argue that there’s an ecological logic to their dominance of the landscape. Sit with the question long enough, and the likeliest explanation becomes hard to ignore: The single-minded attention to cattle is mostly about preserving the power, profits, and land access of those who benefit from the system as it currently exists.

It’s just one example, but it demonstrates why the environmental and social and political conversations can’t be parallel conversations. They’re the same conversation, even if they’re not always being had at the same time. That’s not just because it’s inconsistent, even hypocritical, to advocate for a holistic approach to farming, and yet not embrace the widest possible spectrum of human concerns. In measurable, concrete ways, the environmental aspect of regenerative agriculture likely cannot be decoupled from its social and political context—even if some of the movement’s most high-profile adherents don’t seem to realize it yet.

—

Cornelia Li

“I don’t want to sound like I hate regenerative ag,” Silvia Secchi, a natural resources economist in the department of Geography and Sustainability Sciences at the University of Iowa, told me. “But it’s honestly a last-minute front.”

For Secchi, whose research focuses on land-based energy production, water quality, and adaptation to climate change in the Mississippi River Basin, there is no climate solution—there can be no regenerative agriculture, more broadly—until the U.S. addresses its policy of systemic agricultural overproduction.

Silvia Secchi

Silvia Secchi is a natural resources economist in the department of Geography and Sustainability Sciences at the University of Iowa.

In her view, much of the conversation around regenerative agriculture serves to “talk about the benefits of conservation without talking about the cost that our overall policies have had.”

“The attitude is, let’s talk about the benefits of conservation without talking about the cost that our overall policies have had,” she said.

It starts with the federal crop insurance program, which guarantees farmers a price per bushel of commodities like corn, soy, and wheat. Secchi says that policy—which was instated with the 1933 Farm Bill—incentivizes farmers to plant as much as possible, operating larger and larger farms. Why not: if the government pays you a base rate to plant by the acre, you might as well try to plant as many acres as you can, all the way up to the river bed.

“If you really are into regenerative agriculture, you need to start talking about the crop insurance subsidies that allow farmers in Iowa to farm in the two-year flood plain,” she said, referring to the risky practice of farming near a waterway, which can pollute rivers and streams with agricultural runoff even without a flood. “Their subsidies allow for this massive moral hazard: Farmers essentially have no downward risk because, if they lose their crop, they get compensated.”

But this dynamic has frequently been self-defeating, leading to what some academics call a “production treadmill”: Overproduction tanks prices, thanks to the basics of supply and demand, which then requires more production to make up for lost income. In the U.S., we now produce so much shelled corn that it’s nearly worthless, selling for between 5 and 12 cents per pound over the past year. Yet government subsidies mean it can still be profitable to plant more and more corn.

The environmental consequences of this policy have been widely covered in the press. Today, more than 70 percent of Iowa’s 36 million acres are devoted to crop production—there’s hardly any public land to speak of, and the public waterways are heavily polluted with chemical farm runoff and livestock manure. In December 2020, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources found that 58 percent of the state’s waterways are “impaired,” or too contaminated to meet the standards for their designated uses. When I lived in Iowa City in the early 2010s, air and water quality alerts were a frequent occurrence. The Iowa River snakes right through the middle of town, a murky blue-green spine, and no one would ever consider swimming or fishing in it.

In theory, that’s the kind of damage that regenerative agriculture is supposed to recuperate. And research does show that practices like cover crops, buffer-strips, and livestock integration can help reduce reliance on chemical inputs, while doing more to ensure that substances that are applied stay in the ground, instead of seeping into waterways. Still, from a climate mitigation standpoint—the framing that’s gotten by far the most attention, and is the primary rationale behind recent moves by Congress and the Biden administration—it makes little sense to integrate regenerative practices into the existing system.

A grain plant operated by Cargill, Inc. in East St. Louis, Illinois, on the Mississippi River.

USDA/Preston Keres

Yes, some of the practices associated with “regenerative” can help build up soil carbon. But when those practices are layered on top of a resource-intensive approach to farming, their value becomes dubious. Cover crops won’t change the fact that agriculture, especially in Grain Belt states like Iowa, relies heavily on fossil fuels, which are used to produce synthetic fertilizers, power irrigation pumps, and keep diesel combines running.

It’s strange, when you start to think about it: All the talk about paying farmers to sequester carbon largely avoids discussion of how much they’re already emitting. The carbon benefits of “regenerative” practices, after all, are meaningful only if they substantially outweigh the emissions cost of production. But do they?

Many “regenerative” frameworks do little to address one of the central issues: state-sponsored overproduction of commodity grains.

I posed this question to Mark Lambert, vice president of agriculture at the venture capital firm Quantified Ventures, who helped to design the Soil and Water Outcomes Fund, a vehicle for paying farmers to adopt sustainable practices that has sold credits to customers like Cargill and others. His response surprised me.

“We are not quantifying whether each farm operation is achieving net neutral or net negative carbon emissions overall,” he wrote in an email. “We are concerned only with the below-ground carbon pool. The broader emissions associated with production don’t negate this sequestration. Taken on the whole, we recognize that each farm will likely be a net emitter of GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions. What our program is helping farmers do is reduce that overall GHG profile by increasing sequestration in soils.”

That makes sense: All improvements are welcome, and it’s better than if those farmers had done nothing. Still, this stance becomes problematic if, as Lambert said, his farmers are still net emitters of GHG emissions. As long as their farming processes pollute more than they conserve, they’re still making the problem worse, not better. It’s a way of talking about benefits without accounting for the costs of production.

Cornelia Li

What makes this even more troubling is that those benefits—which are not net benefits—are then sold on the open market. This allows companies to say that carbon credits make them carbon-neutral, even though the farms that generated those credits aren’t themselves carbon-neutral. In the worst-case scenario, poorly regulated carbon markets based on flawed or overly general assumptions would allow farms that still pollute the climate to generate carbon credits of uncertain environmental value, sold in turn to polluting corporations who can then claim they’ve achieved “zero emissions.”

The issues don’t stop there. Secchi explained that commodity crop production—as currently supported by federal policy—is inherently tied to a range of other economic and environmental crises. Take the federal ethanol mandate, which requires a certain amount of corn-derived ethanol to be blended into gasoline, and is in part an attempt to stablize corn prices. As Mario Loyola writes in The Atlantic, that policy has resulted in an astonishing 38 million acres of land—a mass larger than the state of Illinois—being planted with corn for ethanol. That’s a questionable land use decision, since all that corn feeds vehicles and not people. It’s also had the pernicious effect of making fossil fuels cheaper and more desirable, making it harder for cleaner energy sources to gain a foothold in the marketplace.

All that subsidized grain has another indirect environmental consequence: It makes meat cheaper, too. Most of the corn and soy American farmers grow isn’t directly fed to people, but is used instead for animal feed. That’s a financial win for meatpackers, since it lowers the cost of growing animals for human consumption. But using huge amounts of land to grow food for cows, pigs, and chickens makes little environmental sense, especially given the significant associated greenhouse gas emissions—and interpolating regenerative practices will do little to change that.

“I don’t believe there is a single cattle producer in the country that is excited about sending the calves they worked so hard to raise on a double-decker truck 800 miles away to a feedlot to be poisoned by grain. But that’s what the system dictates they have to do.”

—Zach Ducheneaux, executive director, Intertribal Ag Council

“Since we are paying for the overproduction of corn, we are therefore as taxpayers indirectly responsible for the greenhouse gas emissions that that generates,” Secchi said. “We are then also responsible for all the greenhouse gas emissions downstream, from the livestock industry, which these subsidies support—because it’s cheaper to grow the hogs and chickens and whatever. And then we want to pay farmers to fix the problem? It’s mind-bogglingly stupid.”

In this context, she called regenerative agriculture “a massive deflection.”

Zach Ducheneaux, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe who is executive director of the Intertribal Agriculture Council, an organization that promotes economic development and conservation in tribal communities, agreed that it’s illogical to try to fix state-sponsored overproduction with piecemeal on-the-ground farming changes. As a cattle rancher, he’s seen the way that the existing system absorbs individual decision-making power, making it harder for farmers to produce food the way they otherwise might. For him, there is no point in talking about “regenerative” until we address the forces that compel farmers to focus on yield at the expense of everything else.

“To me, regenerative agriculture is what every producer would do if they were freed from the confines of this commodified system,” he said. “I don’t believe there is a single cattle producer in the country that is excited about sending the calves they worked so hard to raise on a double-decker truck 800 miles away to a feedlot to be poisoned by grain. I fundamentally don’t agree that that’s what every cattleman wants to do. But that’s what dad did, and that’s what grandpa did, and that’s what the system dictates that they have to do.”

“Regenerative ag—if it’s true—should rock the fricking boat.”

—Silvia Secchi, natural resources economist, University of Iowa

“By the same token,” he continued, “I don’t think there’s a single row crop or grain farmer out there that is looking forward to the prospect of putting Roundup on their field in the spring. But they have to, because the system that they’re in dictates that they grow at least X number of bushels on X number of acres to make their note payments so that they can continue to keep the farm operating. To me, ‘regenerative’ is what these guys would all do if we could free them from that yoke of financial determination that predates them.”

Despite this, Secchi said, she’s seen a notable reluctance to question long-held assumptions. That’s true even in the academic world, including among those who study agriculture’s potential for transformative change. Part of the resistance is cultural: The emphasis seems to be on finding ways to incrementally improve the existing system, even if that system is fundamentally at odds with broadly agreed-upon goals. But the spaces she inhabits are also largely dominated by white men with close industry connections, people who have a lot to lose if they alienate more powerful interests. She’s based in Iowa, after all, where the influential Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture was recently defunded—a move that critics say was political retaliation for scientific findings that were unfriendly to big agribusiness.

“These are all ecologists. They should be able to think in terms of systems,” Secchi said. “But what they’re doing is not thinking in terms of systems. What they’re doing is fiddling at the margins, so they can keep their big labs open. Keep all the federal funding and funding at the state level flowing. Not upset anyone, not rock the boat. But regenerative ag—if it’s true—should rock the fricking boat.”

—

Handy Kennedy, the founder of the AgriUnity Group—a cooperative run by Black farmers in Cobbtown, Georgia—prepares feed for his cows.

Models of collective ownership can increase farmers’ success by pooling resources to purchase land, reduce overhead costs, and allow for market expansion.

The links between subsidies, overproduction, and environmental damage aren’t the only touchy subjects in the conversation surrounding regenerative agriculture. In some quarters, there’s also a reluctance to talk about land ownership. There’s a desire to invest in new science and embrace new tools without confronting the way scaled up, ever-more-mechanized farming directly and indirectly served to consolidate—and homogenize—ownership of U.S. farmland, paving the way to our current crises of equity and environment.

In an illuminating analysis, Portland State University scholars Megan Horst and Amy Marion synthesize years of academic research, showing how federal programs focused on the overproduction of commodities mostly benefited wealthy landowners—who were, and still are, mostly white men. These landowners had the resources to compete in the race for larger and larger farms, while less-well-off farmers, tenants, and laborers—disproportionately people of color—were, as one Farm Security Administration official put it in 1938, “shoved aside in the rush toward bigger units, more tractors, and less men per acre.”

According to Romero-Briones, many of those who use the term “regenerative agriculture” have avoided reckoning with this uncomfortable history.

“We need to talk about land access and land acquisition for Indigenous people. We can’t get into conversations about regenerative agriculture without that,” Romero-Briones said. “But a lot of the conversations that are happening kind of go up to the fence—you’ll talk about soil and carbon, but we don’t want to talk about land ownership. We’ll talk about grazing cattle on more or less acreage. But we don’t want to talk about who owns those acreages.”

An astonishing 97 percent of U.S. farmland is owned by white people. Can we take regenerative agriculture seriously if its adherents don’t talk about that?

We know who owns those acreages. In the U.S., according to the most recent available USDA data, a full 97 percent of U.S. farmland is owned by white people.

That’s not an accident. The story of American agriculture is in many ways a story of dispossession and exclusion, an extensively documented saga of broken treaties, forcible removal, slavery and incarceration, racist violence and intimidation, grinding systemic discrimination. That history continues to this day. While white co-founders shill their food startup ideas in the pages of glossy magazines, Native producers and entrepreneurs struggle to attract basic press interest and investment—just the way other people of color, and also women, struggle to secure the capital needed to run viable food businesses. In 2019, an investigation by The Counter showed that USDA’s stated record of recent civil rights accomplishments was based on highly misleading data—data that helped to obscure decades of discrimination, while spurring the continued pattern of land loss that has been epidemic among Black farmers and other farmers of color.

While white co-founders shill their food startup ideas in the pages of glossy magazines, Native producers and entrepreneurs struggle to attract basic press interest and investment.

Left, Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) research assistant Kyle Kootswaytewa checks on the health of black tomatoes in the IAIA Demonstration Garden, in Santa Fe, NM, on Sept. 11, 2019.

USDA / Lance Cheung

This history is not a backdrop. It’s fundamental to the social, political, and environmental challenges that we face today. The lack of representation in American farm ownership can’t really be separated from Iowa’s unbroken landscape of corn. They’re two sides of the same problem.

“What is regenerative ag without considering the consequences of Jim Crow and what it meant for Black farmers? Without considering the fact that the whole state of Iowa was essentially just given to white farmers who started tilling the heck out of it and overproducing—and now we’ve had to have policies in place for a century to take care of that overproduction?” Secchi said. “That’s what regenerative ag has to face if it wants to be real, in my opinion. Otherwise, it’s just greenwashing.”

Others agreed that, without a strong social and political foundation, regenerative agriculture was doomed to be a facile intervention. As Chappell put it, quoting the food sovereignty advocate Maria Whittaker: “Sustainability without justice is merely sustained injustice.”

In theory, you would think that proponents of regenerative agriculture—farming that makes the world better—would want to address these issues head-on. But just as there’s a curious silence on the topic of farm subsidies and overproduction, I found entities in the regenerative ag space to be curiously silent on the topic of racial injustice, specifically when it comes to land access.

Entities in the regenerative ag space are curiously silent on the topic of racial injustice, specifically when it comes to land access.

In his analysis of the many definitions of “regenerative,” Newton, the CU professor, found that about 17 percent of academic studies and 40 percent of practitioner websites included language related to social issues and community well-being. But when I asked him to look for mentions of racial parity specifically, he found none in a scan back through the data.

That omission is indicative of the overall tone. The Regenerative Organic Alliance, for instance, has incredibly detailed metrics for what farms must do to use the term “regenerative” on consumer-facing products, from agreeing to regular sampling of soil carbon to passing metrics about increased biodiversity. There are even metrics related to equity: The program helps to certify that farmer-supplier contracts are fair, that workers are being paid honest wages, and that fields are free from child labor and sexual harassment. This is rigorous, well-thought-out stuff. And yet nowhere is racial justice, specifically, mentioned. Nowhere does the program seek to address the fact that white people own 97 percent of the land.

I asked Jeff Moyer, CEO of the Rodale Institute, who sits on ROA’s board as executive chairman about why issues related to racial justice were omitted.

“I would say that we probably haven’t done a thorough enough job of trying to incorporate that thought process or those principles in that language into our standard,” he said. He cited that ROA’s standards are nimble and able to evolve through a process involving the company’s board of directors—the still-young certification, he said, only debuted in the summer of 2020.

“A lot of the conversations that are happening kind of go up to the fence—you’ll talk about soil and carbon, but we don’t want to talk about land ownership. We’ll talk about grazing cattle on more or less acreage. But we don’t want to talk about who owns those acreages.”

—A-dae Romero-Briones

“We can’t expect everything to happen all at once. The team that we’ve assembled has done an amazing job to create a dynamic standard that is being well received in the marketplace. Companies and food packagers are saying this is exactly what we’ve been asking for, exactly what we need. And we’re rolling it out as rapidly as we can with a fairly small budget and a very small staff. Is it all-encompassing and perfect? No. But give us time. We’ll incorporate these things, and that’s one of the pieces of language that we need to think about as we progress on this path.”

In a statement, a General Mills spokesperson told The Counter: “In terms of specific goals and metrics around racial equity in our regenerative ag pilot programs, we’re actively exploring how we might do that moving forward.” It also mentioned its sponsorship of events run by other organizations that have been more proactive in their support of advancing equity in agriculture.

In an email, a spokesperson for Cargill said they were “pretty sure we have never been asked this question. I’m not aware of any such definition that includes an equity measure, so will have to check.”

After a 10 days, Cargill wrote back to inform me of a new initiative it had just announced, which will explore ways “to increase the participation and profitability of Black farmers.”

After asking for more time to formulate a response, Danone had not provided further clarification by press time.

From the organizations I spoke to, it seems clear that issues of racial justice and land access are second-tier issues—considerations that aren’t included in initial pilots and programs, but worked out gradually over time. To be fair to them, these issues are complex—and there’s meaningful debate about who, ultimately, is responsible for taking them on.

“We have to grapple with these uncomfortable conversations and discussions around racial justice. We have to do that,” Berhe, the UC Merced soil scientist, who has also advocated for including an equity dimension in definitions of regenerative agriculture, told me. “Where it gets complicated, though, is when you start thinking about how this factors into this specific farms working in a specific way. Should this be a larger societal burden that we all bear together to acknowledge the history that got us to this point? Or do we put all that burden on specific farms and individuals?”

Berhe said she is still grappling with that question. And, ultimately, we may decide that the burden of addressing racial equity in agriculture and land ownership does not fall on the shoulders of specific farmers, corporations, or certifiers, but to the government—which has powerful tools at its disposal to uplift those who have been shut out of food production.

The Growing Climate Solutions Act, a bill currently under consideration by the Senate and co-sponsored by a bipartisan group of more than 30 senators—seems to recognize this. The bill, which would start the process of allowing USDA to certify entities that pay farmers for carbon sequestration, includes language that would require lawmakers to find ways to increase the access of “historically underserved, socially disadvantaged, or limited resource farmers” to land (and, through it, valuable carbon credits)—though it currently offers no specific proposal for how to do so.

It remains to be seen how the government will act. But proponents of regenerative agriculture can’t just ignore this debate. As the writer Sarah Mock recently argued, carbon credits are already making farmland more valuable—further raising barriers to access for those who find themselves excluded from agriculture, while rewarding those who are already wealthy (if not in dollars, then in land). Without a strong equity component, then, climate-farming schemes are likely to worsen social inequality and consolidate land ownership—factors that are correlated, in turn, with environmental degradation.

There is another way, one that could improve both the ethical validity and environmental efficacy of “regenerative,” while addressing the ongoing crisis of equity in our midst. But it will require drawing a bigger circle, and entertaining a broader spectrum of concerns, while facing up to the realities of our shared and shattering past.

—

A great transition is afoot. Nearly one-third of America’s farmers are over 65 years old, and nearly two-thirds are over 55, according to USDA data. The average age of farmers in the U.S. is just shy of 60 years old. It’s an indicator of a generational change that’s already underway: According to some estimates, as 25 percent of farmers retire between 2011 and 2031, 70 percent of farmland will change hands.

The conventional wisdom, in some circles, is that no one will want to replace these farmers when they age out of the business—and no one will need to.

“The fundamental fact is that we no longer need many farmers,” tweeted the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman, in a 2019 thread on the decline of rural communities in the U.S. He shared a chart suggesting that farm productivity had doubled more than five times—an overall increase of 2,400 percent—in the past 70 years. “We just can’t find work for many farmers these days,” he wrote.

In a broad sense, it’s true that farming—especially conventional farming—has become a lonelier, more automated profession that requires fewer and fewer people. In a recent Foreign Policy essay titled “Big Agriculture is best,” two leaders of the Breakthrough Institute—a think tank that advocates for intensive technological solutions to environmental problems—argued that this exodus is a good thing, claiming that “vanishingly few [Americans] live anywhere near a farm or want to work in agriculture.”

But that narrative doesn’t tell the whole story.

For Wizipan Little Elk, CEO of the Rosebud Economic Development Corporation (REDCO), the economic development arm of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, access to the land is about something much more foundational. In a recent keynote address at Regenerative Rising, a Longmont, Colorado-based annual conference on regenerative agriculture, he explained a project he’s involved with, one that involves restoring an eventual total of 1,500 bison on 28,000 acres of Native grassland within the nation of the Rosebud Sioux, or Sicangu Oyate, a branch of the Lakota people.

Of course, the initiative will produce food and generate revenue. But to reduce it only to those crude metrics—yield and profit—would miss the point.

“In the life of a Lakota, my tribe, and particularly for a male, the killing of a buffalo is one of the biggest events that we can partake in and participate in,” he told the audience, assembled virtually by Zoom. “When I killed my first buffalo, it was very meaningful to me and hugely important. I remember afterwards, I turned to one of my friends and said, ‘I’m finally a Lakota man. I’m finally able to be who I was meant to be, by doing this.’”

I’m finally able to be who I was meant to be by doing this. As Little Elk’s example shows, there are those who burn to work the land, who feel their humanity will never be fully complete without it. There is no lack of desire. There are only barriers to access. Tahz Walker is senior program manager of the Farmers of Color Network, a fund that provides infrastructure capital to farmers in the southeastern U.S. as part of RAFI-USA, a nonprofit that advocates for corporate accountability, environmental sustainability, and racial equity in agriculture. In his experience, land access is a defining issue for many of the region’s young, aspiring farmers—and the supply of would-be farmers far outpaces the availability of land.

“A lot of beginning farmers are in the same place,” he said. “They may be leasing land in urban or peri-urban areas, and the land prices have just obviously gone up. So they’re looking at more rural land, and just not having the capital. At the same time, they want to be close to their markets—often, they were already working with a specific market closer to an urban area, and they don’t want to be too far away. They’re having to really figure out, ‘OK, well, these land prices are crazy, how do we afford this?’”

“They’re having to really figure out, ‘OK, well, these land prices are crazy, how do we afford this?’”

—Tahz Walker, director of RAFI-USA’s Farmers of Color Network, on the struggles faced by beginning farmers

In short, many who want to farm find themselves priced out of the market. Farmland prices have soared in the past decade, thanks in part to unprecedented interest on the part of wealthy investors. In Iowa, farmland costs six times what it did in 1990; nationwide, farm real estate value has jumped nearly 60 percent since 2006, according to USDA data—and the emergence of mature carbon markets is only likely to accelerate this trend.

The resulting land access dilemma is common among new farmers, but it’s especially keen for farmers of color. Walker says that the surge in interest he sees is from people who don’t have an immediate history of agriculture or land ownership in their families, or whose connection to the land was severed generations ago. The ones who are able to purchase farmland tend to have something in common: They’re white.

“This is not a knock on a lot of the younger white farmers, but what I’ve seen is that a significant amount of them—not all—come with generational wealth that they can lean on. I know farmers who are like, ‘How did you get this farm so fast, and all this infrastructure?’ And it’s like, ‘Well, we got a loan from our parents,’ or ‘We got a loan from family,’ or ‘We were able to pull trust fund money and cash out on it.’”

A recent report from the nonprofit National Young Farmers Coalition spells out the problem in more detail. It’s not just that white people already own 97 percent of farmland, much of which will be handed down to a family member—or if it doesn’t, may be snapped up by an investor before ever appearing on the open market. In addition to this gap in inherited wealth, farmers of color face any number of additional obstacles, including higher levels of student loan debt, language barriers, discrimination from lending agencies and public farm programs, discrimination by the people and entities selling land.

In this light, Krugman’s tossed-off analysis—“we just can’t find work for many farmers these days”—appears deeply misguided. Plenty of new farmers, many of them people of color, want the opportunity to work the land. They’re simply hitting up against a system that rejects them.

What can “regenerative agriculture” really be if issues related to land access, economic equity, and racial parity fall outside its purview? Ultimately, it can only be a limited, selective, and self-serving framework, one that seeks to strengthen what is already powerful while declining to fix what is broken. As National Young Farmers Coalition’s executive director Martin Lemos put it in a recent op-ed for The Counter: “Without concerted and multiple land policy interventions, we forestall the more just food system that is struggling to be born,” he wrote. “Too little investment would expose how much of our agricultural policy is [in fact] a land-wealth preservation strategy.”

This is where the conversations about environment and equity start to converge even more clearly. A vision of “regenerative” that ignores access and equity would likely be not only incoherent but ineffective, undermining its conservation goals from the outset. After all, pivoting away from a heavily mechanized agriculture obsessed with yield toward a more dynamic agriculture based on ecology would be an unprecedented transformation. That transformation can only be powered by a precious natural resource: people.

—

In a still from Gather, San Carlos Apache food sovereignty advocate Twila Cassadore, right, harvests berries with White Mountain Apache farmer Clayton Harvey.

Renan Ozturk

The case for a more thoroughly populated agriculture becomes clear in two recent studies co-authored by a range of contributors from across academic disciplines and professional industries.

“A critical and underappreciated feature of agroecological systems is that they replace fossil fuel- and chemical-intensive management with knowledge-intensive management,” write the authors of a study titled “Transitioning to Sustainable Agriculture Requires Growing and Sustaining an Ecologically Skilled Workforce.”

In this formulation, the key ingredient isn’t high-tech machinery and expensive inputs. It’s a recipe that requires the expertise, creativity, and watchful eye of human beings.

“With such a small percentage of people trying to do all the farming in the country, we have a huge rupture between people and ecosystems—there’s not enough human care involved.”

—Liz Carlisle, professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara

“For decades, US policies, technologies, and economic pressures have tended to ‘deskill’ rural labor. … Production has shifted to larger farms that specialize in two to three crops or in livestock,” they write. “Such ecologically simplified operations rely on repetitive tasks, heavy chemical and fertilizer applications, and large-scale ‘labor saving’ machines. [But] under a model that pursues productivity as the primary goal, neither food security nor sustainability has been achieved, and a critical resource—farmer knowledge—has been eroded. As a result, the single greatest sustainability challenge for agriculture may well be that of replacing non-renewable resources with agroecologically skilled people.”

These are scholars, scientists, and activists with a keen sense of our dire environmental predicament. And yet they’re saying the greatest sustainability challenge we face may not be climate change, or population growth, or depleted soil. It might be something much more immediate: finding a way to get more knowledgeable people on the ground.

“With such a small percentage of people trying to do all the farming in the country, we have a huge rupture between people and ecosystems—there’s not enough human care involved,” said Liz Carlisle, a professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and co-first author of the study. “In an agro-ecosystem that’s being managed regeneratively, there would be a lot of monitoring and observation and adjusting and care of plants and soil. We have people farming tens of thousands of acres, but they can’t possibly observe at that level what’s happening.”

First Nations Development Institute

As one recent study put it, “production using clean technologies is human capital intensive.”

Above, Sicangu Oyate youth help to process buffalo at a Rosebud Sioux facility.

It makes sense that regenerative agriculture, in its inherent complexity, will require more skilled practitioners. As one recent study put it, “production using clean technologies is human capital intensive.” In a recent Senate Agriculture Committee hearing on regenerative agriculture, John Reifsteck, Chairman of the Bloomington, Illinois-based Growmark farming cooperative, made a plea for more funding for on-farm assistance. “We’re going to be asking a lot of our farmers to implement these plans on our farms,” he said. “That’s going to take a lot of technical expertise. Today, we simply do not have the capacity—with government agencies, with extensions—to add that kind of expertise on every farm.”