Courtesy West Philly Bunny Hop

Giving and volunteerism ebb and crest with pandemic fatigue, civil unrest, and the weather.

In April, Jena Harris and Katie Briggs ventured into two West Philadelphia parks to give out free produce and pints of homemade soup. The two friends, both freelance chefs and food activists, weren’t sure what to expect.

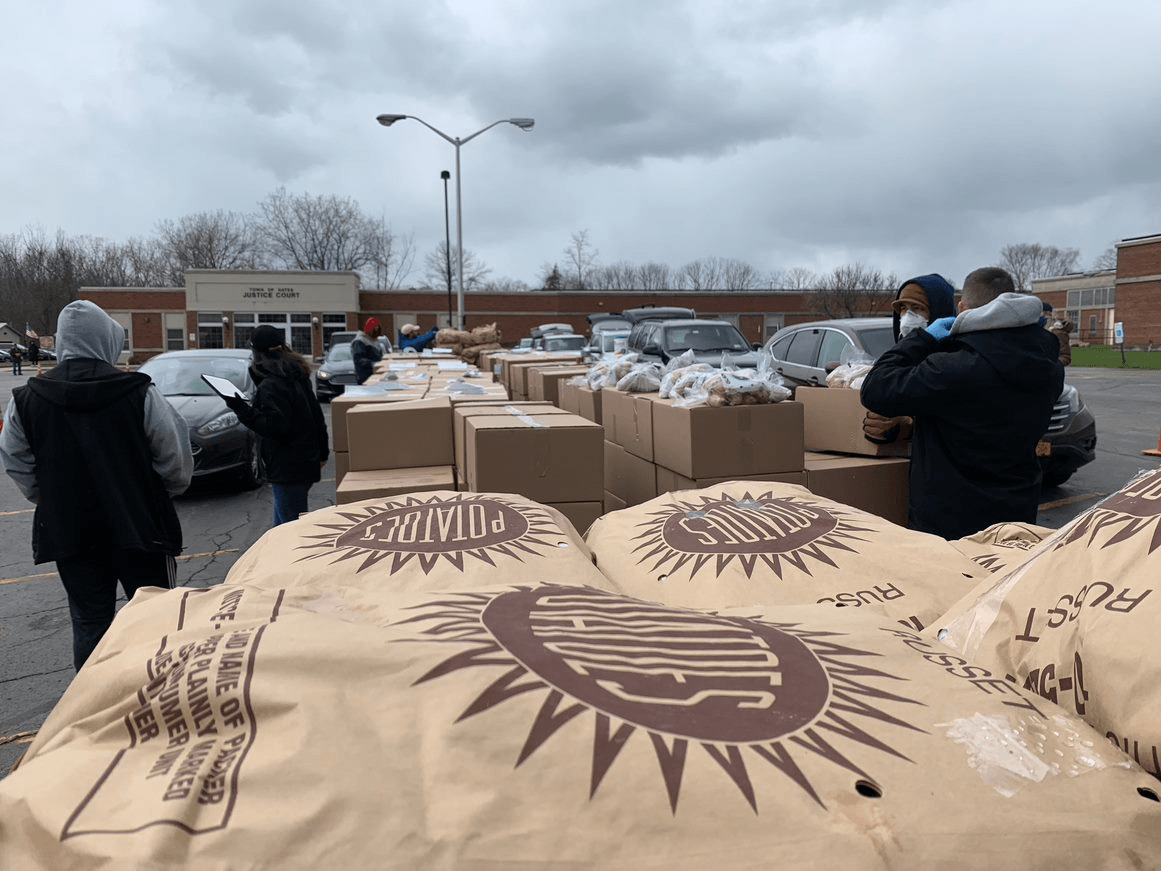

Pictured above: Volunteers with the West Philly Bunny Hop pack produce shares at the group’s warehouse space in Yeadon, PA.

But people came, masked and gloved, to the distribution sites in the Cedar Park and Cobbs Creek neighborhoods, where gentrification has displaced longtime residents and exacerbated inequality. Soon all the soup was gone. Harris and Briggs did it the next week and the next, adding rolls of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and bottles of bleach procured from restaurant-supply stores when supermarket shelves were empty.

They called their project the West Philly Bunny Hop, spreading the word on Instagram and among friends and neighbors.

Nine months into the pandemic, thousands of mutual aid groups like this one—formed in response to fear, confusion, and lack—are still doing their best to make sure communities have what they need.

West Philly Bunny Hop volunteers distribute food and supplies at Malcolm X Park.

Courtesy West Philly Bunny Hop

Some thrived from the swell of early support when laid-off neighbors had time to help and more money. Many have expanded beyond providing meals. Still others head into 2021 unsure how long they can serve communities more in need of relief than ever.

Bunny Hop grew steadily for its first few months, leaning on donation and volunteers. It widened its reach to offer as many items—groceries, meals, cleaning supplies, diapers—as community members needed. But the program exploded during the uprising after the police killing of George Floyd in June. Briggs and Harris had already begun collecting snacks, bottled water, and relief items for protesters when the fight came to them: Malcolm X Park, one of their flagship donation sites, is located just a few blocks from where Philadelphia police teargassed protesters and residents.

In the chaotic week that followed, Bunny Hop scrambled to accommodate a rush of donations—not just supplies, but tens of thousands in small-dollar Venmo transfers—and interest from new, mostly white volunteers eager to get involved. Once they caught their breath, Harris and Briggs saw that they could go beyond providing supplies. They began making microgrants to other groups and activists and long-term commitments to organizations like Morris Home, the nation’s only residential-recovery program specifically serving trans and gender-nonconforming people.

Many [mutual-aid efforts] have expanded beyond providing meals. Still others head into 2021 unsure how long they can serve communities more in need of relief than ever.

“We shifted from doing food distribution and household essentials to being a hub for a number of resources,” Harris said. “We became a resource for the community in a different way.”

Today, Bunny Hop is a multisite program with dozens of volunteers and partnerships with other mutual-aid groups in Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware. Those big batches of homemade soup have been replaced by a team of cooks preparing up to 1,200 healthy, ready-to-eat meals in a commercial kitchen each week. Organizers source food donations from local businesses and farms, purchasing fresh items with their cash reserves. They collect supplies at a warehouse space just west of city limits. They’ve also begun selling prepared foods and produce shares to subsidize additional distributions.

“I definitely didn’t expect it to become what it has become—only because in the year prior, doing this type of work, it was really difficult to get support, to get people to participate,” said Harris, referring to a free breakfast program at 1149 Cooperative, the restaurant, shared kitchen, and community space she ran in South Philadelphia in 2019.

Bunny Hop’s success could be considered a best-case scenario for a new mutual-aid group: flush with funds and volunteers; savvy with online promotion and well-connected in the community; and able to share supplies or funds with nearby groups.

But it’s a challenge for some mutual-aid groups during Covid-19 to get the supplies and people power to meet community needs.

Bunny Hop’s success could be considered a best-case scenario for a new mutual-aid group: flush with funds and volunteers; savvy with online promotion and well-connected in the community; and able to share supplies or funds with nearby groups.

Keeping a mutual-aid effort going can be particularly difficult in rural communities, even when the need for resources is significant. People in Surry County, North Carolina, started a small mutual-aid group in March to coordinate low-risk volunteers to get essential supplies to high-risk individuals.

But by fall, the group was on indefinite hiatus. Over the summer, volunteers had been pressed to return to work. Being in a rural county with an aging population also made it difficult to connect with those in need of support and to source essential supplies.

A few hundred miles northeast in Virginia, another rural group, Buckingham County Mutual Aid, has encountered similar challenges. When the pandemic hit, Danny Loren and a few friends who’d done hurricane disaster relief made a website and put up fliers, encouraging those who needed help to get in touch. They connected with mutual-aid groups 90 minutes away in Richmond, where they’d load up on supplies or get cash donations to purchase items.

“There’s so many different communities within this huge county that mutual aid out here looks a lot more like trying to connect a bunch of different people [who] aren’t necessarily always going to agree on how things will go in any capacity, but trying to make sure that everybody’s alive and well,” Loren said.

After a few months, with donations running low, the group made the decision to plug into more formal networks like food banks, church food pantries, and game meat donation programs to source supplies. Those choices went against the mutual-aid mantra of “solidarity, not charity,” but helped their work continue.

In addition to delivering food, Loren’s group is connecting people to other resources that are no less necessary—but more available in rural spaces.

“One man might have a riding mower, another man might have a machine to dig a well,” they said.

Even in more populated areas, getting resources to those most vulnerable to the pandemic’s health and economic impacts has become more difficult. When Boston restaurants shut down in March, Alex Gladwell and Kaitlyn Sullivan were laid off from their restaurant jobs. They were able to access unemployment benefits, but their undocumented co-workers were not.

“I think the harsh reality is that a lot of people are going back to their lives.”

In response, they founded Restaurant Worker Mutual Aid of Greater Boston, pulling together a small group of volunteers and using the restaurant Sullivan managed to store and pack groceries for laid-off industry workers who couldn’t access benefits due to immigration status.

At first, cash donations were flowing in, and though the need was great—all 70 households to which the group delivers have had at least one member contract the virus—Gladwell and Sullivan kept things going with a core group of about 10 volunteers.

But as Boston began slowly reopening as summer turned to fall, many of their helpers went back to work, and donations have dropped off, too. Gladwell, who worked as a server and bartender before the pandemic, estimates that the group has funds to make it through the end of the year. “I think the harsh reality is that a lot of people are going back to their lives, and [this problem] is more background than it is central,” she said. “My goal at this point is to just get to 2021 and continue to re-evaluate.”

While winter cold has forced many mutual-aid groups to relocate indoors, Tucson Food Share in Arizona moved operations outside this fall, to the parking lot of a community center. Organizer Se Collier estimated that the group served meals to an estimated 50 people each week pre-Covid. Now, the group serves several hundred with its three weekly grocery distributions, with numbers nearing 1,000 when cases spike and near the end of each month, when food assistance benefits run low.

The group, an outgrowth of the long-running Tucson Food Not Bombs, avoids burnout for volunteers and organizers by keeping involvement low pressure. “We have a culture of encouraging people to not do stuff that they don’t feel like doing and celebrating people taking breaks, or opting out of things that they had previously said that they would do,” Collier said. “When you get tired, you leave. And when you get excited, you show up.”

Avoiding burnout is something West Philly Bunny Hop’s Harris and Briggs have had to force themselves to do.

“This is a crisis we’re living through. With this mutual aid, people are coming together, and we’re planting seeds.”

“This work is honestly never-ending,” said Harris, who still holds her full-time job as a buyer for an independent grocer in the city. “Being able to let people know I have to stop at 5 because I could go until midnight, and making a point to pause and reflect, has helped make us successful so far and let us plan for what those next shifts and changes look like.”

With no end to the pandemic in sight—and its economic impacts sure to last long into the future—groups that have the volunteer power, infrastructure, and funding or donations to keep going have no plans to stop.

“It’s always been kind of understood between us that this needs to continue forever,” Briggs said. “I think we both come from a collective spirit as well. How can we share this with everybody?”

Collier agrees. “That’s my retirement fund—knowing that I’m part of a community that extends further than I can even see, where we all are ready to support each other. This is a crisis we’re living through. With this mutual aid, people are coming together, and we’re planting seeds. The more we do that, the stronger we get, and the more people know we can do that, it just keeps growing.”