Kashi

There are two stories to tell about the state of organic agriculture in the United States. The first is a success story, the inspirational tale of a fringe industry that—in less than two decades—has transformed into a $43-billion-dollar powerhouse. It’s the story of an industry that grows by double digits year to year, long the fastest-growing sector of the overall food market. And it’s the story of a marketing term that’s gained broad recognition in American households, a kind of byword for health and wholesomeness at a time when those characteristics seem to matter more than ever.

But there’s another story here, too. And to tell that one, you only need a single stat:

Less than 1 percent of all U.S. farmland is certified organic.

In other words, organic hasn’t come all that far from its roots. It’s still a fringe movement of sorts, just a tiny sliver of the overall pie.

The 1 percent figure isn’t due to sluggish demand. Quite the opposite: consumers want more organic food than domestic farmers can currently supply, which forces retailers, feed companies, and packaged food manufacturers to bridge the gap with organic imports from other countries. This supply imbalance varies from region to region, crop to crop, but it’s especially drastic in commodity grains. In 2016, 50 percent of our organic corn and 80 percent of our organic soy had to be imported from countries like India, Ukraine, Turkey, and Romania. Until farmers can catch up, imports will continue to prop up American organic, making it seem more robust than it is.

If demand is so great, why don’t more farmers switch over? What’s keeping organic’s market share at that anemic 1 percent?

The answer’s pretty simple: three long years.

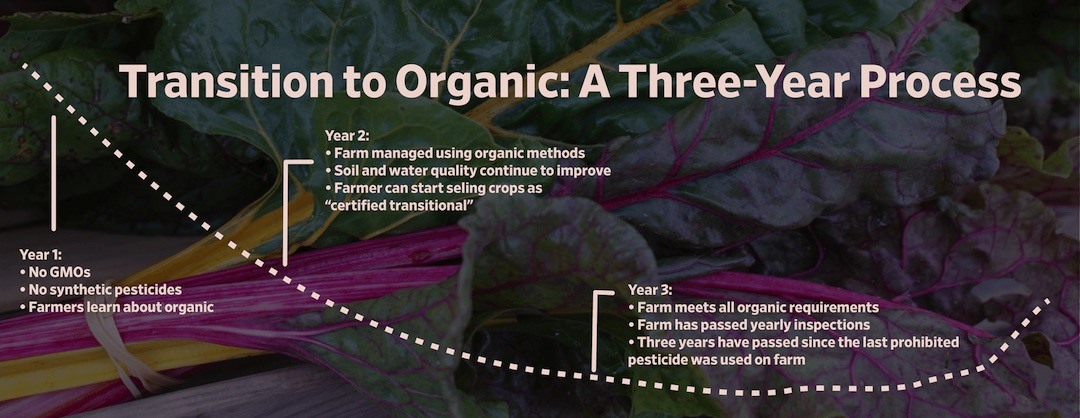

Conventional farmers can’t just drop everything and go organic. According to the way the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) standard is written, conventional farmers must use organic methods for three years before they can call their crops organic. That’s a long time, but it makes sense: organic is primarily a soil-quality certification. For a farm that’s relied on harsh pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, it takes time to rebuild soil health the way organic standards stipulate—with compost, manure, cover crops, and other methods.

But this three-year term of servitude creates an economic conundrum for farmers. Organic is usually seen as a more expensive, labor-intensive production method—one that’s financially justified by the market premium paid for certified crops. Judged this way, that 1 percent figure starts to make more sense: many farmers can’t afford to undertake the three-year transition period without the extra pay.

But a new certification class may encourage farmers to take the plunge. It’s called “certified transitional,” and it’s like organic on training wheels.

Adapted from Quality Assurance International; graphic by The Counter

The best-known program is a joint initiative of Kashi, the Kellogg-owned, La Jolla-based maker of organic cereals and snack bars, and Quality Assurance International (QAI), one of the world’s largest organic certifiers. (Organic certifiers are the companies that audit farms to ensure they’re using the practices they say they are. We’ve got an explainer here.) The idea is that a consumer-facing certification will help educate the public about this in-between period—and, hopefully, convince them that transitional is worth paying more for, at least compared to conventional. If products with the certified transitional seal can command a higher price in grocery stores, the thinking goes, a portion of that premium will flow back to the farmer. The extra money could make the three-year waiting period less dire, and ultimately convince more farmers to risk going organic.

“We heard from a lot of consumers and customers that they like this idea,” says Nicole Nestojko, Kashi’s senior director of supply chain and sustainability. “A lot of consumers have told us they weren’t even aware of the three-year transitioning window, and that once they learned about it they were excited and willing to support it. So that gave us some confidence that it has legs.”

Little green “certified transitional” seals have already started appearing on some Kashi products, though the designation is not limited to them: any farmer or food company that follows the guidelines can receive the seal. So what’s in it for Kashi? In one sense, it’s good branding. The effort sounds like the product of a company strategy reported in 2015 by the Wall Street Journal: using Kashi products as a way to address social and agricultural problems makes a play for relevance in a consumer goods marketplace that, some say, has moved on to fresher faces. But, more immediately, it’s also about addressing the nationwide shortage that frustrates bulk buyers of organic goods. For companies like Kashi, certified transitional puts a new class of feel-good, organic-esque raw ingredients within reach.

Nestojko says the scarcity of organic ingredients has been “a pretty big deal”: there are not enough organic almonds grown in the U.S., for instance, even to meet Kashi’s needs alone. The certified transitional program, then, kills two birds with one stone. It may persuade more farmers to try organic, bolstering the industry’s long term health. At the same time, and more immediately, it introduces a new kind of raw ingredient to the marketplace—one that is not quite organic, but perhaps still good enough for the granola-munching masses.

From one angle, it looks like a win-win. But from another, it may be cause for worry.

“We’re concerned about an ‘organic-lite’ label out there competing for shelf space with organic farmers,” says Nate Lewis, farm policy director of the Organic Trade Association (OTA), which represents the industry. “While we do want to create a system so that producers in transition can get recognition for their efforts, we are concerned about a transitional product … being viewed as ‘just as good, but half the price.’ That’s not our goal.”

And so, last month, the OTA launched a competing transitional certification of its own. At the farm level, the two programs have no substantive differences—though OTA’s program was developed in tandem with USDA, which gives it, according to Lewis, a more robust enforcement mechanism. (QAI can take away a certification, but USDA can deduct civil penalties, conduct fraud investigations, and require corrective actions.) The biggest difference, though, is this: only the Kashi program offers a consumer-facing seal. Though OTA also went through the work of developing a standard for food processors and their packaging, it ultimately decided to scrap its version of the label. For now, only the Kashi’s seal will appear in stores; OTA’s certification stops at the farm gate.

Why? Out of concern that “certified transitional” will eat away at, or even weaken “certified organic.”

It’s “kind of a distraction,” Lewis says. “Consumers look for those seals as a shortcut to make their shopping choices. In order to discourage the risk of transitional products competing with organic products, our task force was very adamant that there should be no development of a seal to put on the front of these products.”

It’s hard to estimate how well consumers will understand the transitional certification. (Many still don’t understand “certified organic.”) You could argue that the consumer-facing seal will actually help educate shoppers, as it paints a more realistic picture of what organic farming requires. Still, the new seal may muddy the waters somewhat. For instance, while both transitional programs set a rigorous pre-organic standard on the farm, Kashi’s requirements are a little more lax elsewhere: specifically, for producers of packaged foods.

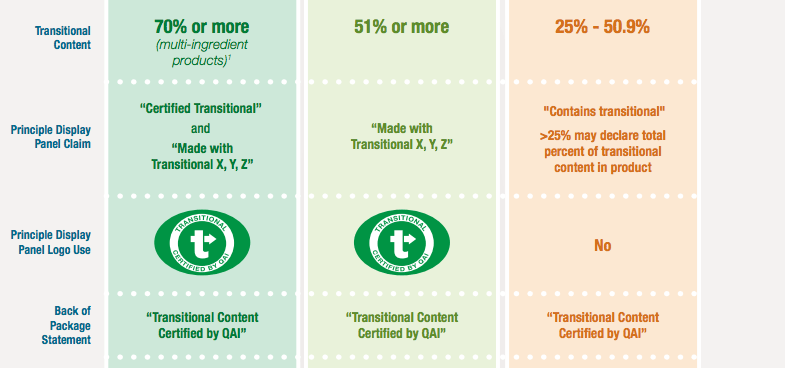

How? Well, organic certification has three tiers. Products made entirely with organic ingredients can be labeled as such—”100 percent organic.” Products that are 95 percent organic can be labeled “organic.” Meanwhile, products that are at least 70 percent organic won’t get the organic seal, but can call out specific certified ingredients in statements like “made with organic oats and raisins.” Kashi’s transitional certification doesn’t quite hold itself to that standard: a product with 70 percent transitional ingredients can be called “certified transitional.” A product that’s only 51 percent transitional can’t make the claim “certified transitional,” but will still receive the eye-catching green seal.

A product with 70 percent transitional ingredients can be called “certified transitional.” A product that’s only 51 percent transitional can’t make the claim “certified transitional,” but will still receive the eye-catching green seal.

Quality Assurance International

These percentages may be lower because there’s not currently enough certified transitional product on the market. But this also means that a company could slap a “certified transitional” seal on a product that was made with 49 percent conventional ingredients. That’s a little slippery, and though it remains to be seen how well the public will understand the new seal, or whether transitional will dilute the organic brand, one thing’s for sure: it could be a good financial development for companies like Kashi. If consumers are willing to pay organic-like premiums on a product that’s really 49 percent conventional, that amounts to a sizeable markup.

But wouldn’t it help farmers, too? In concept, at least, some of that money would make its way back to the farm. And the strength of Kashi’s program, after all, is that it adds a premium on the retail shelf. Without the little green seal, and without the higher market price it’s supposed to command, how will producers ever afford the three-year waiting period? How will OTA’s version make farmers any money if its certification goes silent after harvest?

Lewis says some farmers are already seeing better returns. Transitioning farms certified under the program have locked in better contracts with buyers already, he tells me: one common arrangement, called a “forward contracting agreement,” is for processors to pay extra for transitional crops now, in return for a guaranteed supply of certified organic crops later. Some organic crops are in such short supply domestically, in other words, that food companies are willing to essentially finance cost of a farmer’s transition—just to lock in contracts with soon-to-be organic suppliers while they still can.

Ultimately, it’s still unclear which solution will do the most to ease the burden of transition—the business-to-business approach, or the pretty green seal on the box. The competing approaches are about a larger philosophical question, too: who should pay? Should the cost of going organic be shouldered by the farmer, the foodmaker, or the shopper?

“There’s definitely a need to share the financial burden of transitioning to organic for producers. Everyone is on the same page about that,” Lewis says. “I think there’s not necessarily going to be one approach that’s always going to be successful.”

Meanwhile, farmers around the country are looking to both programs as they make their pivot. For Richard Gemperle, owner of Edelweiss Nut Company, an almond and speciality tree nut farm in central California, the Kashi certification has been an improvement

“The status quo was, well, you just have to grin and bear it for three years,” he says. He started transitioning his crops into organic a few years ago, before the new certification was available, and quickly became daunted.

“I realized this is a much more difficult way to farm,” he says. “It’s more satisfying, but you have to think it through.”

Last year, Gemperle started selling almonds to Kashi for use in their line of “certified transitional” chewy nut butter bars. The new market, he says, has helped make it more feasible for him to handle the increased costs he’s seeing during the changeover. He estimates that he needs to make a 20 to 25 percent premium to break even on all the additional expenses—which include new irrigation systems, and more labor-intensive approaches to weed and pest management. He couldn’t say for sure how much of a premium he’s making from the transitional almonds, but has the general sense that it’s been worth it.

“I’m optimistic,” he says.

Still, what’s working now may not work in five years. Though organic crops usually command a premium, the exact amount varies enough to spook farmers into sticking with conventional. As the agricultural lender Cobank put it in a recent report: “The volatility in the organic price premiums during 2016 has likely raised some questions and uncertainty among producers about the sustainability and consistency of that reward.” For some, the specter of the 2008 recession—when organic prices dropped so low that many farmers were forced to sell straight into conventional markets for no premium whatsoever— looms large. Demand for organic may overwhelm supply right now, but people turn to the cheaper options when the economy starts to falter. And if that happens, demand could dry up pretty quick.

“I have no idea what the premium will be next year,” Gemperle says. “I’ll be pushing this transitional program in our own operations over the next five years, really not knowing what kind of premium I’ll be realizing.”

At this early stage, certified transitional looks like good news for American farmers. But, for now, going organic still requires a leap of faith.