Tod Auman

We used to be a place where our community gathered. Now we’ve lost all that, and our approach is changing in ways we never could have imagined.

Tod Auman is the co-owner of Dundore and Heister, a whole-animal butcher shop in Wyomissing, Pennsylvania. He opened it six years ago after leaving a job in finance. The shop, which he co-owns with his wife, is a labor of love, he says. And it’s a product of nostalgia. Auman, who grew up here, says he was inspired by the neighborhood butcher he used to visit as a kid. Even the name—taken from the region’s Pennsylvania Dutch settlers—is a throwback.

The Counter is seeking short essays about how Covid-19 has impacted American life through the lens of food. How have the pandemic’s emotional, physical, personal, and professional disruptions recast your daily routine, eating habits, and appetite?

Auman feels like an ambassador for local animal farmers, whose economic outlook is dire. The Covid-19 pandemic has closed the restaurants that buy their pasture-raised meats, and the farmers’ markets many rely on may be next. Yet while these producers struggle to reach customers, retail is booming. Across the country, demand for groceries has surged, and meat is no exception. This March, American supermarkets sold over 70 percent more chicken and beef and nearly 90 percent more pork compared to the year prior, according to new market research.

Auman pines for the old days, when small-town butchers were the key connection point between farm and table. His staff breaks down locally raised cows, pigs and lambs, selling the steaks, chops and fats over the counter to dedicated, discerning carnivores—often with samples to taste and a side of conversation. Now, those forms of intimacy are no longer possible. For safety reasons, he’s closed the doors to customers, and converted his business into something more modern—a drive-by retail establishment, one that’s devised new operational practices to suit the moment, and is currently selling more meat than ever, he says. In a conversation by phone, Auman explained how he’s trying to hold onto his vision for a communal, tradition-steeped neighborhood shop during a time of isolation and social distancing.

—Sam Bloch

—

Tod Auman: I come from an investment background, so I’m cognizant of risks. And I’ve always been somewhat of a worrier. So when I started hearing about what was happening in China, I started having conversations about the worst-case scenario. About what we would do as a company.

The first thing we noticed—as we started getting into the belly of this pandemic—is that our store was busier and busier. Then there was a remarkable change in buying behavior. People stopped buying our prepared foods, like breakfast sandwiches and lunch sandwiches, and it became more about the things that could be put in a freezer and stored for an indefinite period.

We’ve seen growth—30, 40, or 50 percent in sales. It’s ground beef, broths, frozen soups, poultry items like frozen chicken—things that are short in supermarkets. We’re getting a huge volume of new customers—people that we’ve never seen before, coming to us because they can’t find these things elsewhere. Many of the supermarkets are out of meat. Trying to manage that has been a real challenge—not only the surge in volume, but the change in the products that people want.

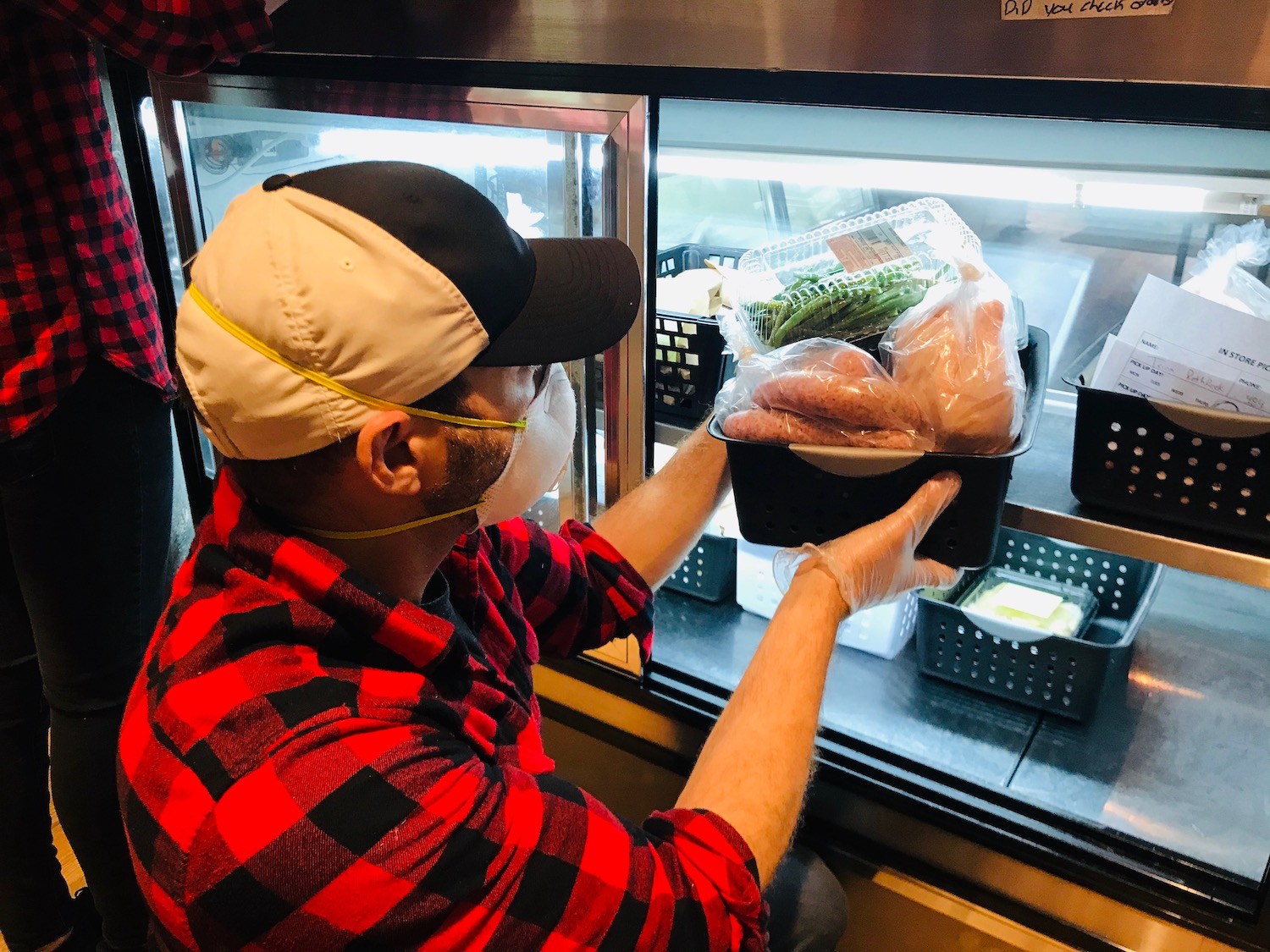

At Dundore and Heister, employees shop for customers and package orders for preordained pickup times.

Tod Auman

The consumer hasn’t been in our store for three or four weeks now. We are only doing curbside pickup. We completely changed our model. So now the store is all about fulfillment. The doors are locked. People call in advance. We shop for them, we package it, we get their credit card, and they pull up to the door at a preordained time. Then we put it in their trunk and they drive away.

To see cars lined up down the street—five or six or seven cars lined up, waiting in an orderly fashion—is somewhat surreal. The store is empty. But there’s all these folks. And there’s no kind of contact. Just to see that, it’s like—wow, this is really happening. I think that, ultimately, curbside is going to be a continuing part of our business—something that we had never imagined. Especially with the unknowns of how long this might last.

Before this hit, we were a place where the community gathered. We’ve always been high-touch—we talk to everyone, we want to give them advice. But now we’ve turned that upside down. We’ve lost the power of presentation. When people come into the store, we want them to be amazed. We want to show them things they never knew they needed from a butcher shop. But now we don’t have that.

Then there’s our people. Behind the mask, these are remarkable people—they are engaging, they can tell our story, they know our farmers, and they can answer questions about our meat. Maybe you came into the store because you heard we had this amazing breakfast sandwich. And that ten-dollar sandwich allows us to start a conversation with you. People come in, and they meet Mark, our head butcher, and they ask about our farms, and see our retail cuts of meat, and maybe in the future they buy a dry-aged steak from us. And that is, at this point, lost.

Every single day, we are trying to adjust, on the fly, to make sure we’re protecting our customers and staff.

So what happens if we have to go online? If in-person is what we do really well, how does that transition? How does our company adjust to that? Those are the questions I’m asking now.

As of this week, when my staff comes into the building, we’re taking their temperatures. And they’re wearing masks. Our customers are wearing them, and they might be comforted if we are, too.

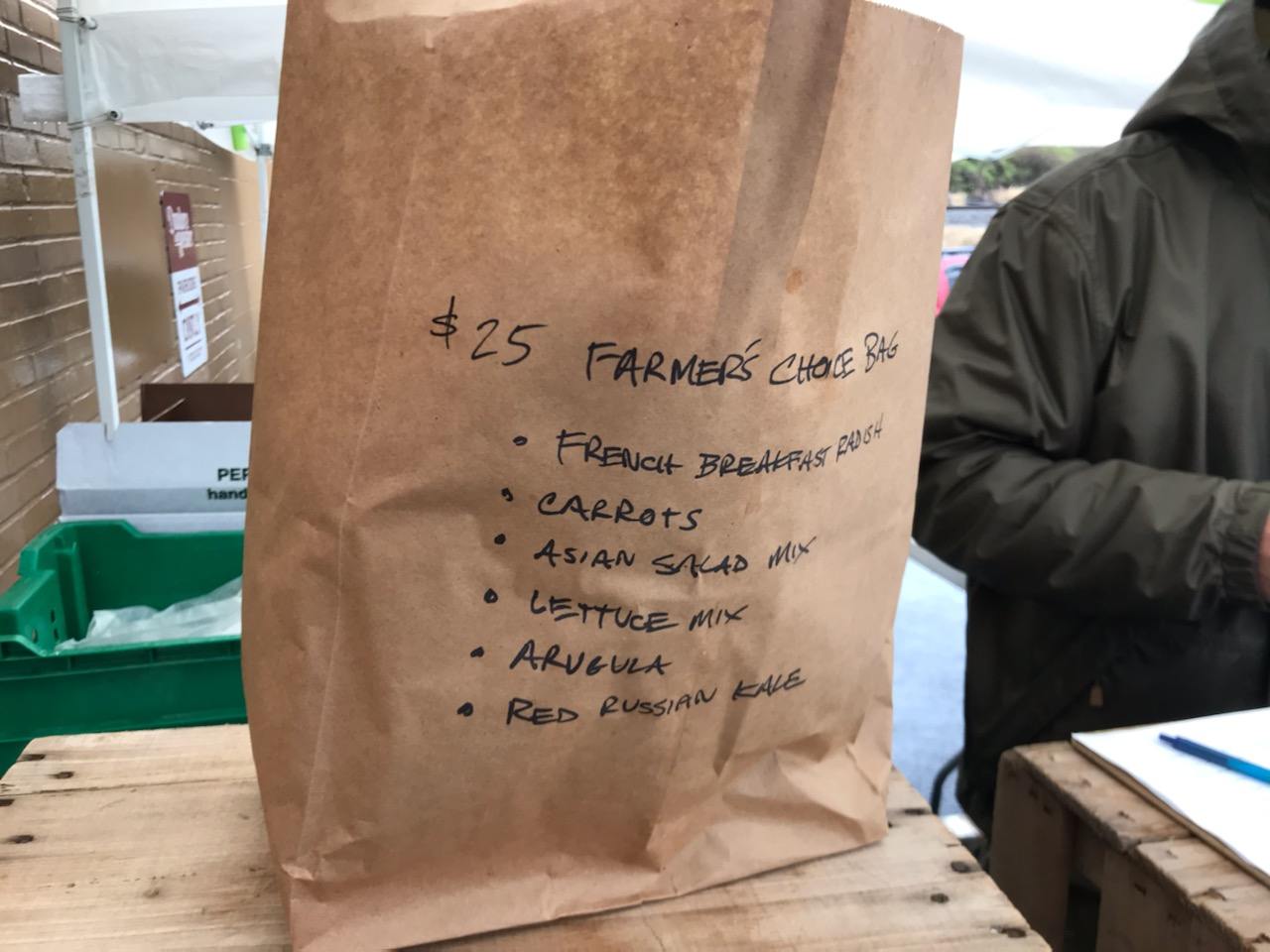

A bag of groceries for pickup

Tod Auman

And in a small space, it doesn’t hurt, right? We should be doing everything we possibly can to keep our people safe. Having cleaners there, sanitizing—every single day, thinking about, are we doing enough? Watching the news—what’s the latest information? Every single day, we are trying to adjust, on the fly, to make sure we’re protecting our customers and staff. When social distancing is impossible in a small shop, what can you do?

One of our farmers in Bedford, Pennsylvania had 95 percent of his meat going to restaurants in Pittsburgh. So we’re talking about buying more meat from him—maybe another steer—to try to help him out.

Tod Auman

Dundore and Heister shortened their hours of operation from seven to five days a week.

Why wouldn’t I buy that extra steer, since the demand is there? I think it’s just purely fear of the unknown. What happens if someone gets sick? It’s not like I’m gonna bring in another team from another town to fill the role. If someone were to get sick, heaven forbid, we would have that extra inventory. Then what do you do? We don’t want to get too far over our skis. There’s an element of risk there. I don’t know what’s going to happen the next day. Or the day after that.

We’re now open five days a week, instead of seven. I feel like I’m crisis managing every day. So having two days to regroup and strategize about what’s next is healthy for the business, healthy for the team—and frankly, it allows us to resupply from our farms, to keep up with demand. This is about doing what we can to remain open, while at the same time, keeping our customers and team safe.

There’s a sense that this is our duty. And that’s completely inspiring. This feeling of—no, we are not on the frontline of healthcare, or first responders, but our role, to get nourishing, local meat to the consumer, is valuable. And it really is emotional for a lot of people. It’s almost, like, from 9/11—let’s roll.