Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: Getty/Arctic-Images, Lena Beck

Pacific Northwest rains wash the toxic chemical that weatherizes your car tires into the watershed—a death sentence for salmon. The Nisqually Tribe and researchers are trying to find a solution.

Highway 7 runs north-south through western Washington, carving its way through a landscape sparsely dotted with residences, farms, and a general store. The flush of late winter rain characteristic of the Pacific Northwest gives way to a green April, complete with blossoming trees and chirping birds. Ohop Creek, which runs under the highway, is part of the regional spawning grounds for coho salmon—juvenile fish spend the first phase of their lives here, before beginning their journey to the sea.

This land is the ancestral home to the Nisqually Tribe, which currently has more than 650 enrolled members. The 5,000-acre reservation is nearby, and the Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources does restoration work along Ohop Creek. The Nisqually people have a deep cultural tie to salmon—it is not only a mainstay of their traditional diet, but intrinsically linked to their identity as a fishing people. The Tribe has been actively involved in salmon recovery efforts for decades, and since late 2020, they’ve been specifically working to protect coho, which are being killed by a chemical we spread simply by having cars.

Just over a year ago, scientists in Washington identified 6PPD-quinone, which is used to weatherize car tires, as a chemical that is acutely toxic to coho salmon. Every car that drives along the two-lane Highway 7, or even parks in the area, contributes to the problem. In the small valley where the road crosses Ohop Creek, the Nisqually Tribe and their partners, including Seattle-based nonprofit Long Live the Kings, have installed a biofiltration system that they hope will intercept the chemical, and keep the fish alive.

—

In the fall or early winter, coho salmon leave the open ocean and begin a long swim up freshwater streams to spawn. They deposit their eggs, completing the cycle that will yield another generation of the silver fish that have been a cornerstone of the Pacific Northwest diet for generations. In 2019 alone, there were 27 million pounds of coho harvested for consumption in the U.S.

As they swim upstream, adult coho often come into contact with urbanized watersheds in cities like Seattle and Tacoma. Over the past two decades, scientists and residents have noticed something disturbing. Pre-spawn coho in these urban areas seem to suddenly take sick, become disoriented or dizzy, and die within hours.

“Very visible, almost like spiraling, almost like drunk,” said Zhenyu Tian, one of the researchers who identified 6PPD-quinone as a problem. “Gasping for air.”

Tian, now an assistant professor at Northeastern University, formerly worked as a research scientist for the Center for Urban Waters at the University of Washington, Tacoma. While he was there, he was the lead author of a paper published in December of 2020 identifying 6PPD-quinone as a toxic material for coho salmon. Tian and his team used a cutting-edge method for chemical analysis called high resolution mass spectrometry, which can identify each chemical in a water sample based on its molecular weight.

“It’s pretty remarkable for us in the salmon recovery world to be able to pinpoint it so precisely.”

From there, Tian and his team were able to figure out that 6PPD-quinone was the problem.

The chemical protects car tires from cracking when they come into contact with the ozone, but when it reacts with the ozone it transforms into 6PPD-quinone, and is highly toxic.

The damp, rainy climate of the Pacific Northwest, and the impermeable surface of pavement, are a lethal combination: Polluted rainwater flows across pavement, carrying not only 6PPD but chemicals from car exhaust, fertilizer from lawns, and anything else you might find on a city street or residential neighborhood. When the runoff hits the urban watershed, it starts killing fish.

Once the Nisqually Tribe knew what the enemy was, they could figure out a response. “It’s pretty remarkable for us in the salmon recovery world to be able to pinpoint it so precisely,” said David Troutt, natural resources director for the Nisqually Tribe, who first heard of this issue at a meeting of the Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Council in late 2020. “It was terrifying, because we’re all driving cars with tires. But it was exciting, in that we finally had a smoking gun that we could deal with.”

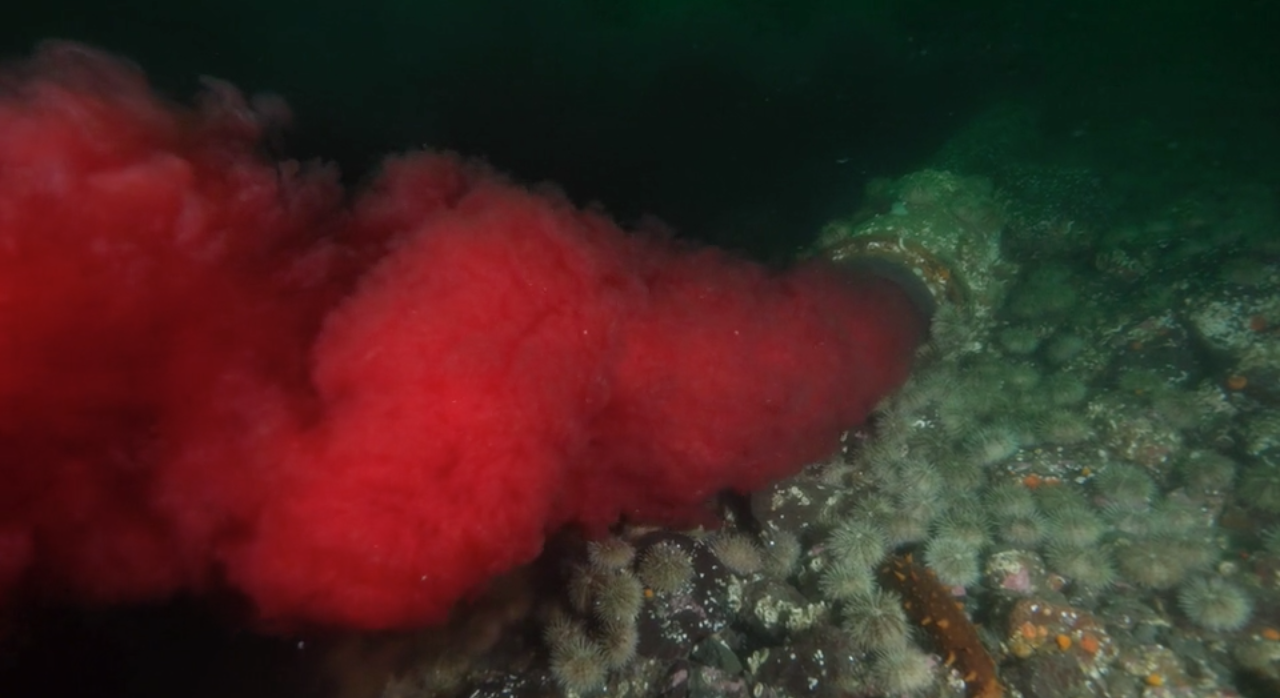

Due to the Pacific Northwest’s rainy climate, polluted rainfall flows across pavement, carrying not only 6PPD but other chemicals that hit the urban watersheds which start killing fish.

Lena Beck

According to Troutt, the problem will require multiple solutions. Source elimination—removing 6PPD from tire production—is the obvious priority, though there is hardly an instant fix. “Finding a salmon-safe, eco-safe alternative as an ozone protection for tires is critical, and it’s got to happen on an urgent time frame,” he said.

But there will be legacy effects for 15 or 20 years, he said, even if an ideal alternative was found tomorrow. In addition to getting rid of 6PPD, Troutt said, we need to find better ways to filter stormwater runoff before it carries toxic chemicals into our waterways.

That’s where the Nisqually Tribe’s biofiltration system comes in; the Tribe hopes it will prove to be a scalable, effective way to protect the ecosystem and the coho that are such an important part of it.

Partnering with Long Live the Kings, a Seattle-based nonprofit dedicated to preserving and reviving salmon in the Pacific Northwest, the Nisqually Tribe recently set up its first pilot installation along Highway 7 at Ohop Creek, to collect water as it runs off the road, channeling it into a dumpster-size box where it can be treated—filtered through a mix of sand and organic matter before being released back into the surface waters.

“Finding a salmon-safe, eco-safe alternative as an ozone protection for tires is critical, and it’s got to happen on an urgent time frame.”

The system was contributed by Cedar Grove Composting, following several experiments led by Jenifer McIntyre, one of the Washington-based researchers who has emerged as a leader in this effort. Most recently, McIntyre collaborated with Cedar Grove Composting and the city of Bellevue, Washington, to pilot test some ‘BUR’itos—Bioretention Urban Retrofits that, like the Nisqually Tribe’s prototype, aim to increase treatment, in this case in stormwater retention ponds. That project showed that the retrofit successfully removed more chemicals, reducing overall toxicity of the stormwater. The installation along Highway 7 was informed by the success of these bioretention systems, but designed to be mobile, and used in harmony with existing stormwater drainage systems.

McIntyre testified before the U.S. House of Representatives in July of 2021 about the threat of 6PPD-quinone—and, while she is not certain what impact her testimony had, researchers have also been collaborating with the Washington State Department of Ecology, the U.S. Tire Manufacturer’s Association, and others to try and decrease the amount of this chemical that enters the waterways, through both regulation and education. The Washington State Department of Ecology has been collaborating with industrial, municipal, and other facilities that convey identifiable and discrete sources of discharge into surface waters, to brainstorm what future regulation may look like in Washington state. These entities hold permits with the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System—the program which regulates sources of discharge in the United States, as authorized by the Clean Water Act.

—

According to Tian, several questions remain. What mechanism is at work between 6PPD-quinone and the coho? Is it in the brain or the bloodstream? What other species are affected by this chemical? How about humans? The coho that swim upstream to spawn are already at the end of their lifecycle, and are not the ones that humans eat, but the full impact of 6PPD-quinone remains unknown.

The Nisqually Tribe set up its first pilot installation along Highway 7 at Ohop Creek, to collect water as it runs off the road, channeling it into a dumpster-size box where it can be treated—filtered through a mix of sand and organic matter before being released back into the surface waters.

Lena Beck

Tian believes that the answers to many of these questions will be found in the next five years or so. The bigger problem, he says, will be figuring out how to get rid of all the 6PPD already out in the world.

Back in the valley, where Highway 7 and Ohop Creek intersect, Troutt hopes that the singular biofiltration system is just the beginning. Based on the results of the pilot program, the Tribe and their partners hope to install more of them in the area, and encourage their implementation across the region. There may be areas where the water flow rate overtakes the ability of these biofiltration systems to filter it, but Troutt and the Nisqually Department of Natural Resources are already encouraging state representatives to install the systems wherever feasible, to enable salmon to spawn without the threat of this life-ending chemical.