The cultured meat company’s top-secret “Blue Sky” team found a new, unprecedented way to grow meat in the lab. Less than a month later, its leader had been dismissed and the team was gone.

On April 2, employees of Upside Foods, a leading cell-cultured meat startup, received a strange companywide email. It included a digital “watermark”—a security measure that would tell the company exactly when and by whom it had been read. The message was a surprise: Nicholas Genovese, an Upside executive who was one of its three original co-founders, was no longer with the company. No reason was given for the abrupt departure.

Above: Upside Foods co-founders Nick Genovese, left, and Uma Valeti, right, share a cultured chicken tasting in a still from the documentary Meat the Future. Between them stands KC Carswell, center, another executive who suddenly left the company earlier this year.

In fact, Genovese had been unceremoniously fired, according to two people with knowledge of the situation, who say he also wasn’t kept in an advisory role. If the email itself was strange, the timing was downright bizarre. At Upside, Genovese, a distinguished and widely respected cell biologist with several key patents under his belt, had led a small, three-person innovation team internally referred to as “Blue Sky.” Under his leadership, Blue Sky had very recently achieved a significant scientific breakthrough: a novel cell-culture device that could produce lab-grown animal cells better than anything else Upside had achieved before. The project wasn’t relevant to Upside’s more immediate plans for commercialization, but it was scientifically significant. According to court documents reviewed by The Counter, one employee involved with the project said she felt the invention was a transformative step forward—a scientific advancement that was worthy, she said, of a Nobel Prize.

Yet within weeks of this breakthrough, Genovese was gone—and the rest of his team followed, resigning just days later. That included Napat Tandikul, a tissue engineer who had co-invented the Blue Sky device with Genovese, and who made the Nobel Prize comments, and Samir Qurashi, a pharma industry veteran and cell procurement scientist.

Together, the three made for an elite team, and their collective departure was a poorly-timed shakeup for the company. Upside was then gearing up to open a cultured meat pilot plant in Emeryville, California, one of the first and largest in the world, a 53,000-square-foot space in a former grocery store building that it finally opened in November. Though the Blue Sky team’s work was not directly related to the plant, which showcases the company’s core technology—proprietary bioreactors that are code-named “Elvis”—the optics were less than ideal, and the departures were not publicly announced.

At the same time, Upside, like its competitors, is under increasing pressure to release its first commercial products—though federal regulations still make the sale of cultured meat impossible in the United States Even if such an approval is eventually granted, commercial production may never be feasible at larger scale. In September, I reported on the industry veterans who say that intractable, potentially unsolvable scientific problems still remain. One exhaustive study, commissioned by a major funder in the alternative protein space, found that lab-grown meat may never be cheap enough to make sense as human food.

Yet despite the daunting challenge of bringing an unprecedented product to market, Upside decided to part ways with its top scientist. On April 1, Genovese was summoned for an after-hours performance review with Uma Valeti, the former cardiologist who co-founded Upside Foods with him in 2015, and Jaci Kassmeier, a company HR executive. The April Fools’ Day meeting took place at a Starbucks in Emeryville, not far from Upside’s headquarters in Berkeley. Genovese was asked to hand over his keycard right there at the table. He never again returned to work.

Why would Upside fire a scientist so clearly capable of advancing its mission?

The circumstances of Genovese’s departure have not been previously reported. They’re also difficult to reckon with—because, by all appearances, he seemed to be an ideal co-founder. Upside Foods (formerly known as Memphis Meats) was the world’s only lab-grown meat company when it declared its intention to feed the masses with cellular agriculture in 2015. Today, other competitors have joined its ranks, but Upside is arguably the best known.

In the last six years, under Valeti and Genovese’s leadership, the company has raised more than $200 million dollars in funding. Its backers include celebrity investors like Richard Branson, Bill Gates, Kimbal Musk, and Whole Foods CEO John Mackey, as well as multinational meatpackers like Tyson Foods and Cargill. The company has been the recent subject of growing profiles in The New York Times, Fast Company, and Bloomberg. Upside’s journey has even been chronicled in a recent full-length documentary, Meat the Future, that underscores the disruptive potential of its goal—the futuristic dream of meat without slaughter.

Genovese had played a crucial role in generating all that hype. He led the bioprocessing team that helped to produce the first lab-grown beef meatball in 2016, a milestone that put the company on the map; under his leadership, successful chicken and duck prototypes followed in 2017. Now, the company will face its toughest challenges without the man who led the development of the most talked-about intellectual property from its crucial early days—firing him weeks after his team smashed internal records with its new, next-generation meat-growing device.

The question is why. Why would Upside fire a scientist so clearly capable of advancing its mission? Why did his team members resign so quickly in the days that followed? And why would it keep the details about his departure under wraps? The company has not alleged any impropriety on Genovese’s part. And his scientific prowess seems to have been greatly appreciated by his co-workers.

“Nick was a leader of both the scientific inquiry and the scientific execution that contributed to building Upside Foods’ product portfolio, in addition to their process development and their next-generation technology,” said one former employee, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitive circumstances. “All aspects of the science that are successful, from my vantage point, in my time with the company, have been under Nick’s watch and his execution.”

It’s a mystery with no clear answer. Upside Foods did not answer the specific questions I asked by email, citing the need for privacy for matters related to personnel, but a spokesperson did provide the following written statement:

Got a tip? Email the author securely at [email protected].

“Nick will always be one of the co-founders of UPSIDE Foods, and his contribution to the company is invaluable. His role at the company has changed to better align with his personal career goals and our longer term business needs. We are not able to comment further given the confidentiality of personnel issues.”

Genovese himself seems to hold no grudge against the company. When reached by phone on Sunday night, he said he hopes to see Upside succeed in its mission, and added he did not want to say anything that might be taken as disparagement of the company or its products.

“Napat and I worked together as a small innovation team to design, assemble, and operate a next-generation meat cultivation system whose technology we believe has the potential to, at least in part, address some of the most challenging technological hurdles facing the cell-cultured meat industry,” he said. “As the sole inventors, we had both assigned our ownership of this novel technology to the company. I am grateful for the resources made available within the company enabling our work on this project, and hope that the technology we developed will be applied to advance the manufacture of cell-cultured meat products.”

Genovese wasn’t the only member of Blue Sky to depart under murky circumstances. In April, Upside sued Tandikul for intellectual property theft. The company alleged that, on Sunday, April 11—10 days after Genovese’s firing—she downloaded thousands of confidential company documents and deleted them from her work computer, resigning the following day. The details of that lawsuit complicate the picture, and offer a glimpse into the secretive world of cultured meat startups, while providing little clarity about why Upside would dismiss its co-founder and alienate his team at the peak of their success.

Tandikul joined Upside as a research associate in December 2019; ultimately, she was promoted to senior research associate and assigned to Blue Sky. (The name reflected the team’s experimental, hail-mary approach and was a nod to its slogan—”the sky’s the limit.”) She did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

“Blue Sky was tasked with developing the Company’s next-generation, transformative technology, a process for cultivating cell-based meats that produces a far greater yield for less money,” the company wrote in its complaint, which goes on to describe the project as “critical to the company’s future.”

By Upside’s own admission, Tandikul’s invention was unprecedented—within the company’s walls, and maybe beyond them.

“Blue Sky has developed a tissue cultivation process that obtains more biomass per unit of surface area than any other Memphis Meats technology,” it wrote in its filing. (The company would not announce it had changed its name until later, on May 12.) “Indeed, just weeks before Tandikul’s fateful departure, the group broke Memphis Meats’ record for biomass conversion efficiency, i.e. the ability to make substantial amounts of meat from nutrients in a cost-effective manner. Upon information and belief, no competitor has developed a similar cultivation process or achieved equivalent results.” (A company spokesperson says Upside’s core technology has since eclipsed those records.)

Tandikul, who is originally from Thailand, gave a name to the device: KPG, a reference to pad krapow gai, a Thai basil chicken dish that is one of her favorites. KPG was a potentially paradigm-shifting milestone, according to Upside’s court filing—one that could allow the company to create not just ground meat products like cultured burgers and nuggets, but “high-quality” cultured meats that “will [be] indistinguishable from that harvested from livestock.”

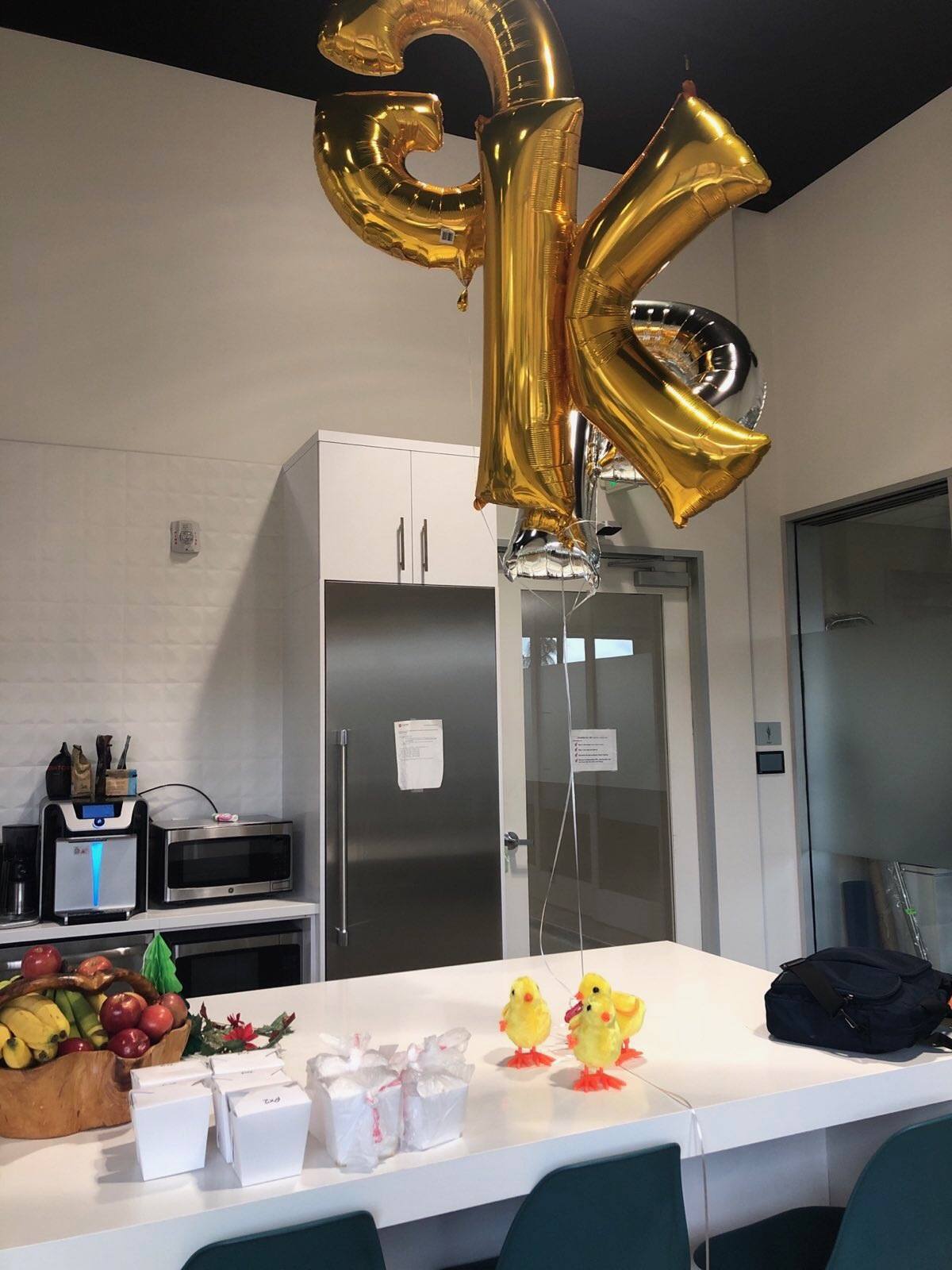

The development was not a secret within Upside Foods. On March 9, Qurashi, the third member of Blue Sky, threw a modest celebration to honor the team’s success. He posted news about the promising results to a company Slack channel, inviting others to join Blue Sky in enjoying some delicious lunch. The photo included with his message showed a preview of the display he’d created: rows of Thai food in takeout boxes sitting beside tiny, wind-up toy chicks tied to silver and gold party balloons. The balloons spelled out the reason for the occasion in three shiny, floating letters: K-P-G.

An April 9 photo posted to Upside Foods’ company Slack, obtained by The Counter and shown above, demonstrated how a members of the Blue Sky team hoped their accomplishments would be received: with Thai food and celebratory balloons. A few weeks later, everyone on the team had left the company.

The festive mood didn’t last long. Less than a month later, Blue Sky’s leader—Genovese—was fired, though Upside’s court filing says that he simply “left.”

“Tandikul, who was close to her manager, did not immediately resign upon news of the manager’s exit, but stayed on for another two weeks,” Upside’s complaint reads, alleging that “she [resigned] not to work with new leadership, but to steal Memphis Meats’ confidential and trade secret information.”

The ongoing lawsuit has yet to be resolved. The complaint paints Tandikul as a colleague distraught by Genovese’s departure, wanting to retain possession of her invention. It also alleges that she helped an unnamed employee enter the office late at night to take a box of materials potentially related to the project. (According to a company spokesperson, the lawsuit was less concerned with the box—it was most focused on recovering the digital files Tandikul had downloaded.)

“Memphis Meats faces the imminent threat of irreparable harm, arising from Tandikul’s breach of her Employee Agreement because the information is highly sensitive and provides Memphis Meats with a clear competitive advantage,” reads the complaint.

But Tandikul’s defense suggests that she had no desire to take the documents, and may have done it inadvertently. On May 12—the same day Upside announced its name change—lawyers from both parties updated the court by Zoom. Tandikul’s lawyer at the time insisted that his client had no interest in retaining the documents in question and simply wanted the matter settled. The lawyer, a California corporate attorney named Douglas M. Wade, later left the case because Tandikul stopped paying him; he had previously cited her financial troubles in the May court update, including her need to borrow money to buy a new phone after her devices were seized for forensic analysis as part of the suit.

Tandikul is currently in Thailand, according to court documents, and could not be reached for comment for this story. But two former co-workers described her as a brilliant, talented, and widely beloved colleague who spoke memorably about her commitment to the challenge of growing meat from cells. Instead of being someone who was dishonest or disgruntled, she was described as being deeply invested in the company’s mission and culture. She was known for hosting watercolor painting lessons for other colleagues and for baking cookies to share with others at work.

“Napat Tandikul is an intellectual force with unrivaled passion for science and the potential positive impact of the cell-based food industry on our world,” said one former colleague, in an emailed statement. It went on: “She takes on all challenges with such a precise attention to detail, one would think she created the Scientific Method herself. Only her warm humanity—constantly providing support in the lab and as a friend—exceeds her scientific ability. If Napat is indicative of the people working to build the future of cell-based foods then this industry truly can evolve and flourish.”

When I reached him by phone, Genovese praised Tandikul’s dedication, scientific mastery, and technical skill, while speaking about her personal kindness and generosity. “She always had a very positive attitude, and raised everyone’s spirits who were around her,” he said. “She’s an amazing person. There’s not many people like her on this planet.”

So how to explain that all three members of the Blue Sky team, just weeks after their breakthrough, were no longer employed? Qurashi, a veteran scientist and cell procurement expert from the pharmaceutical industry, also resigned in the days after Genovese’s departure. According to an Upside spokesperson, both Tandikul and Qurashi were offered roles on other teams, but chose to depart instead.

At least one other senior scientist has also moved on. KC Carswell, Upside’s vice president of process development—one of the executives directly overseeing the Emeryville pilot plant—has also left the company; the circumstances of that departure, which was previously reported by Business Insider, had been unclear. But a spokesperson from Upside provided a statement from Carswell that said the choice to leave had been totally routine, rooted in a decision to move to Australia and be closer to family. The company also pointed out that it had hired Robert Kiss, a widely admired biotechnology veteran who had long been a mentor to Carswell, in October, along with other strategic hires that were timed to leave no gap in expertise.

With the final details of the lawsuit still unresolved, Upside may already have moved on. In a recent video interview with Bloomberg News, Valeti was credited as the “founder,” not co-founder, of Upside Foods. The rebranded company’s new logo, an oversized heart, is not only an appeal to empathy but a reference to Valeti’s origins as a cardiologist—another sign that Upside’s future rests solely with him.

This is a developing story. The Counter will make updates as they come in.

December 13, 2021 at 1:25 PM EST: This piece has been updated to include subsequent comments and clarification from Upside Foods. An earlier version of this story described Upside as being headquartered in Emeryville; the pilot plant is in Emeryville, but its corporate office in in Berkeley.