Last month, Chinese buyers announced they were canceling their orders of American soybeans. It was a stunning reversal by the United States’s number one export customer after decades of growth, brought about by a back-and-forth, tariff tit-for-tat between the two countries. At the time, some analysts, including a former chief economist at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), told me that a soybean surplus, which would inevitably be the result of the lost business, is nothing new.

After all, part and parcel of the farming business is being able to adapt to unforeseen changes, like record rainfall or an invasive pest infestation. But those changes are typically more an act of God than they are an act of President Trump. It turns out that a trade war, and loss of business from one of one of America’s largest agricultural importers—second only to Canada—is pretty bad for a surplus. Especially if that surplus is one for the record books.

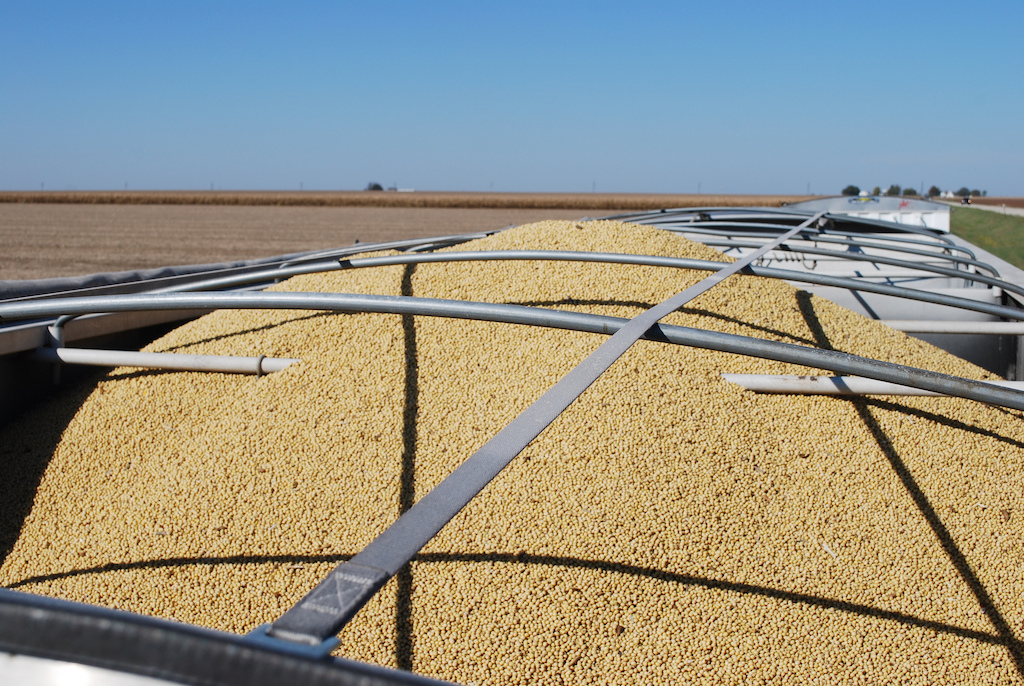

So how big will the stockpile be? Abbott reports the modern-day low of 92 million bushels was set in the fall of 2014. By September, 430 million bushels of soybeans, or a five-week supply, will be in storage. A year from now, when next spring’s crop is ready for harvest, the unsold carryover from this season would stand at 785 million bushels, or 10 weeks’ worth of soybeans.

Of course, those figures probably don’t include the 70,000 tons of Louis Dreyfus soybeans that were aboard the Peak Pegasus cargo ship, and on their way to China, when the agricultural tariffs were announced and fall orders were canceled. After weeks of bobbing aimlessly at sea off the coast of the country, at a cost to the Amsterdam-based commodities trader of $12,500 a day, the ship docked at the port of Dalian on Saturday, suggesting the cargo could be unloaded, and become one of the first soy orders to be slapped with a 25-percent markup.

As I reported late last month, a record crop of soybeans without a major buyer could inspire farmers to go out and buy more grain bins while they wait out the low prices. But even storing their commodities is proving to be more expensive than usual, given that corrugated steel also costs more now as a result of the tariffs.

“Soybeans were always kind of the money-maker, basically,” he told me last month. “You’d always look at soybeans versus corn, with your corn inputs versus corn outputs. You know, that return on investment, soybeans were always looking good.”

This fall, North Dakota is forecasted to have the country’s eighth-largest soy harvest, with the planted acreage there outpacing corn by more than two-to-one.

As has been tweeted, European buyers have emerged to scoop up some of the historically cheap American product. But the potential demand won’t be anywhere close to the scale of the Chinese, as the European Union currently imports, in total, only one-sixth of the amount of soybeans that China does. In an interview with Politico and The South China Morning Post, a Chinese agricultural minister estimated that under a new trade deal, European purchases of American soybeans would be less than one-half of what China used to buy from us annually.

Politico is also reporting that, since the tariffs were announced, Chinese companies have begun looking for alternative ingredients for animal feed—the major driver of their soybean demand. The country is also turning to Brazil and Argentina, the world’s second- and third-largest soy growers, to start filling the orders that Americans used to fill. Ironically, as American soybeans hit their lowest prices in a decade, it’s possible that they could end right back up in China, via their new Argentinian buyers.