Not just tap water: the WOTUS rule affects almost everything on your plate.

As we reported Tuesday, President Trump has begun the process of dismantling the Waters of the United States (WOTUS, also called the Clean Water Act) rule, an Obama administration policy that expanded the definition of federally-regulated waters to include the streams, tributaries, and wetlands that feed into major rivers. All told, Obama’s interpretation of the reach of the Clean Water Act covered about 60 percent of U.S. waterways. When Mr. Trump signed his executive order Tuesday afternoon, he called Obama’s rule “a massive power grab.”

None of this garnered a mention in the president’s address to Congress Tuesday night, where the closest Mr. Trump came to talking about WOTUS was a single phrase sandwiched between promises (“….to invest in women’s health, and to promote clean air and clean water, and to rebuild our military and our infrastructure,” according to a transcript of the remarks).

An estimated one-third of Americans get their water from streams that would be regulated under WOTUS.

We’ve heard a lot—from the vocal Farm Bureau, in particular—about how the rule would have been hard to implement and troublesome for landowners. But don’t forget it never actually went into effect: A federal appeal stalled its rollout in 2015, and now that appeal has itself been stalled by the Trump administration, while it reconsiders the rule. Obama’s Clean Water Act regulation was meant to restore the authority to EPA that had been previously revoked by the Supreme Court. (It’s a complicated history. Here’s a New York Times explainer.)

But the Farm Bureau and environmentalists aren’t the only ones who have a stake in WOTUS. What turned into a huge ideological battle over a pretty vague idea of “regulation” (see Civil Eats for a deeper dive on that angle) wasn’t actually about Big Food vs. small food or regulation vs. deregulation or East Coast vs. Rust Belt. Water, by its very nature, flows across state lines and through politically disjunct territories. It doesn’t care whether you’re worried about the government telling you how to farm or the capacity of your city’s filtration system. It only follows the laws of gravity, and what happens upstream—good or bad—affects what happens downstream.

Clean water, then, is about more than just water—it’s present in all our daily interactions with the food system, the bites and sips we take throughout the day. Here are four drinks and dishes a WOTUS rollback would be likely to affect.

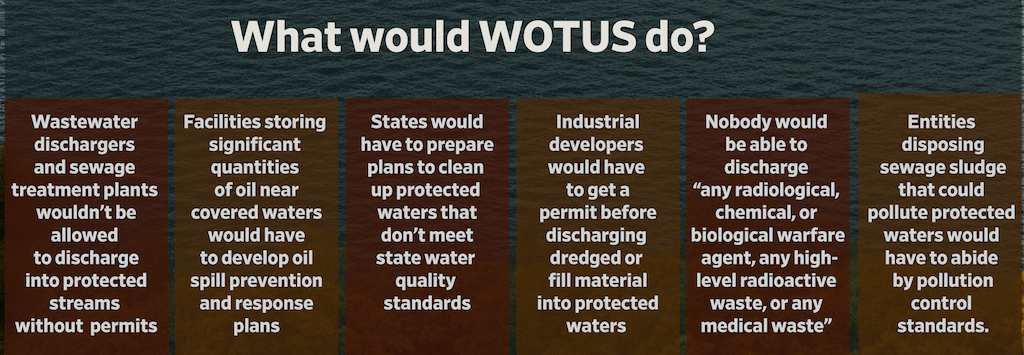

Adapted from research by NRDC

The water we drink.

If you’ve been reading water coverage over the last few weeks, you’ve probably seen an estimate that one-third of Americans get their water from streams that would be regulated under WOTUS. In case you missed it, the Environmental Working Group (EWG) on Tuesday released a report on the subject. It found that about 117 million people get at least some of their water from small streams that would’ve been regulated under the rule, and about 72 million people get more than half their water from WOTUS-affected streams. (EWG also released an interactive map of the counties most affected.)

Most of us don’t drink our water straight out of a stream that flows behind our house. But pollution from streams flows into the water bodies that feed our municipal systems. So that “one-third of Americans” estimate really means that for a third of us, a couple gallons of gasoline spilled somewhere upstream from our house on Monday morning could make its way into our drinking water supply by Tuesday morning.

For New York City, it was cheaper to build a 92-mile aqueduct than invest in an ironclad filtration system.

But Durelle Scott, associate professor of biological systems engineering at Virginia Tech, explains that cities have filtration systems designed to make our water safe to drink, and they’ll keep our water clean as long as they’re working properly. And there are other federal laws in place, like the Safe Drinking Water Act, that put checks on that system. So the implication that our drinking water is in immediate peril isn’t quite accurate.

What a no-WOTUS outcome can do is make our drinking water cost more—in some cases, a lot more. “The issue is that depending on what the water quality is of the stream or river, there might be more processes that are required, or enhanced treatment regulations, that end up being more expensive,” Scott says.

Take New York City, for example: “When New York City had to think about either expanding their plant for water purification or looking for clean sources of water much further up in the watershed and piping that water down where it would need less purification, in the end that was the less expensive option,” he says. That’s right: Rather than invest in an ironclad filtration system, New York City elected to build 85- and 92-mile aqueducts (these tunnels are huge—pictures here) up to reservoirs in the mountains. All because it was less expensive.

Our happy hour special.

Great beer comes from great water. That’s what New Belgium Brewery’s Director of Sustainability wrote about in an op-ed back in 2013, when Obama was still in office and WOTUS hadn’t even been finalized.

Compounds produced by an algal bloom upstream can affect the taste of water downstream even in tiny amounts, like a drop in a swimming pool.

Turns out, brewers are incredibly sensitive to water quality. They site their breweries based on it. Beer is mostly water: Even if a chemical inconsistency doesn’t change the taste of a brew, it can have an effect on other factors, like shelf life and foam pattern. At New Belgium, the brewers and a sensory panel taste their water every day. The brewery relies on municipal water, and staff members are in regular contact with the city to keep the water quality consistent. Still, a small disruption upstream can change the taste of a city’s water even in trace amounts. “Something like an algal bloom can result in … compounds that can be picked up even at parts per trillion levels. We’re talking less than a drop in an Olympic-sized swimming pool where these compounds can be tasted,” Dana Sedin, New Belgium’s analytical lab manager, tells me. (By the way, if your water tastes like beets, it could be the result to a drop or two of those compounds released by algal blooms. Sedin says he tastes it in tap water when he’s traveling sometimes.)

When Becky Hammer, staff attorney at the water program for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), read New Belgium’s clean water op-ed, she realized brewers make the perfect clean water advocates. “We’re always looking for new voices to bring into the conversation, beyond the typical environmentalists. And everyone loves beer, so that was really appealing for obvious reasons. But also, they’re small businesses for the most part, whose experience runs directly counter to this whole narrative of ‘regulations are bad.’”

So NRDC started organizing brewers who supported the rule. It wasn’t that hard to get people to sign on to Brewers for Clean Water—the campaign includes almost seventy breweries today. They wrote letters to Congress, op-ed pieces in their local papers, and submitted comments to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) while the rule was in development. “One of our brewers actually spoke at the ceremony when the rule was signed by the administrator of the EPA,” Hammer adds. (Trump’s executive order signing was attended by Farm Bureau president Zippy Duvall.)

Hammer says NRDC is in the process of deciding what comes next after the multi-year campaign that very nearly succeeded. “Now we’re trying to figure out how we’re going to push back against this new development of the executive order, working with the brewers on that.”

Our oysters Rockefeller.

It seems like a no-brainer, but our fisheries have a pretty big stake in keeping water clean, too. And it’s not just freshwater environments that are affected. “Downstream fisheries and saltwater environments become two of those things that are really important from a food production standpoint,” Scott explains.

“It’s not just about endangered species.”

Just like cities and their tap water, fisheries’ interest in water quality is economic as well as environmental. The Chesapeake Bay alone contributed $3.39 billion in sales and 34,000 jobs to the local economy in 2009. And those numbers don’t even factor in the economic impact of recreational activities on the bay. Pollution upstream can lead to algal blooms and swings in dissolved oxygen and pH levels, which can kill fish and limit recreation. “It’s not just about endangered species,” says Scott.

Our side salad.

Even though the Farm Bureau was a vocal opponent of the WOTUS rule, farms still need clean water for irrigation. Lettuces and spinaches in particular are sensitive to contaminated water—E.coli can be transmitted via animal or human feces, for instance, through surface water or runoff from farms upstream.

Scott says if someone gets sick from produce that has come into contact with dirty water, the financial burden falls on the farmer: “If you’re a farmer … in essence, you’re responsible. FDA regulates it and has a very small number of people that monitor it, but the grower is ultimately responsible for putting out products that are impacting human health.”

“It’s not just about clean drinking water for humans.”

So even though the Farm Bureau opposed the WOTUS rule, the farmers that grow greens still really need to be able to trust the water upstream. The Civil Eats piece I mentioned earlier posits that it was really the livestock farmers and their commodity-producing allies, not the vegetable farmers, who orchestrated the push against the rule.

So, let’s take a “toll” tally: A WOTUS rollback would take a toll on oystermen, brewers, crabbers, lettuce farmers, spinach growers, and water drinkers, among others. But Scott says there’s a way forward if everyone gets a seat at the table: “It’s the holistic balance of all the competing demands that are required in terms of making decisions—social decisions—that we need to do.” That means the cattle farmer upstream has to work with the lettuce farmer downstream, and maybe the hobby fishermen in the Chesapeake bay should chip in to build buffer strips at the farms upstream to help prevent runoff. Scott puts the decision simply: “It’s not just about clean drinking water for humans.”