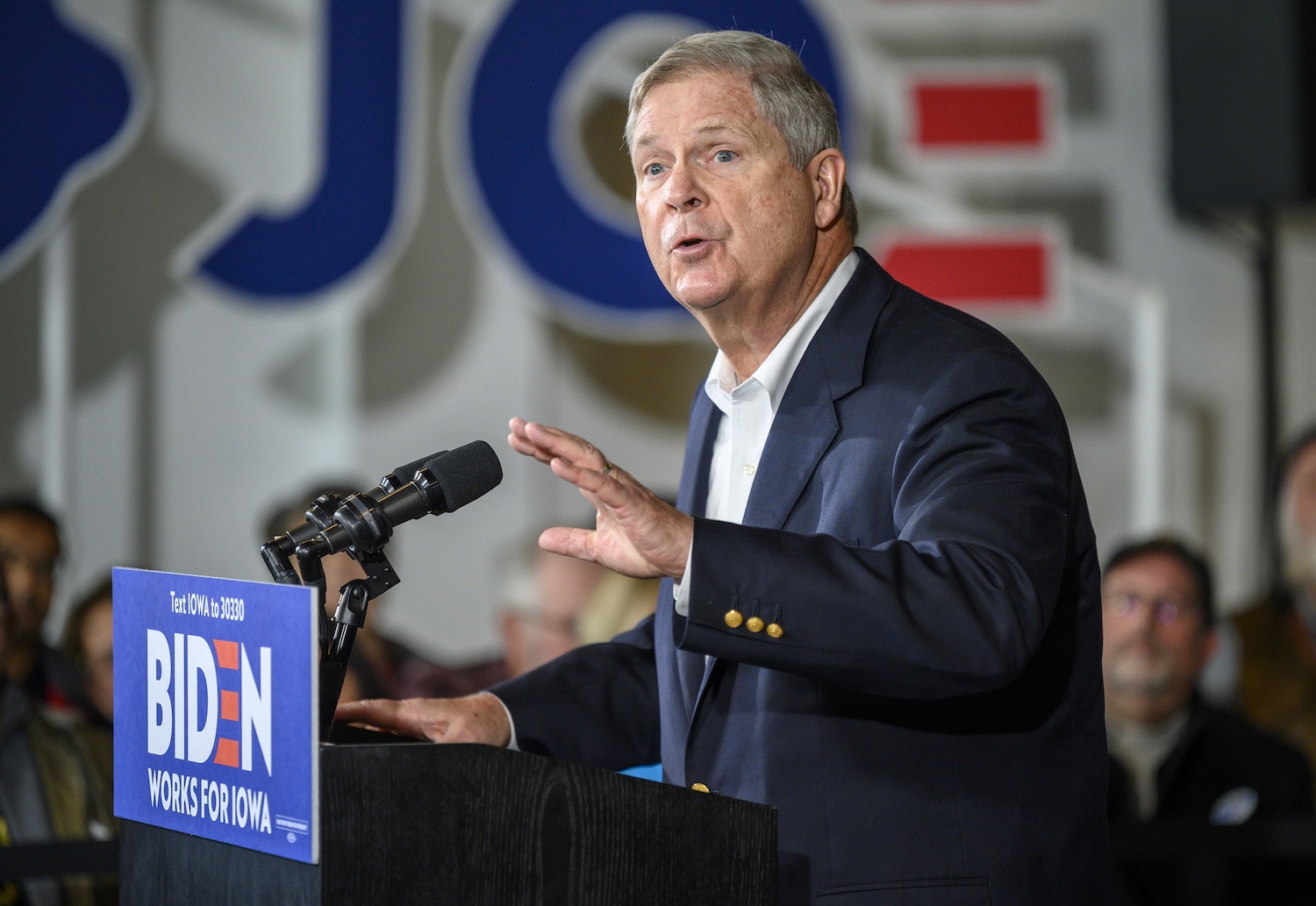

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

The former (and likely future) Secretary of Agriculture faced few tough inquiries.

Former Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack on Tuesday morning faced questions from the Senate Agriculture Committee during his confirmation hearing to reprise the role under President Biden. Despite serious concerns about his past tenure, he is expected to be confirmed with broad bipartisan support. The committee agreed to skip its usual 48-hour waiting period between the hearing and the vote, unanimously advancing Vilsack’s nomination on Tuesday afternoon. Democratic Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York has pledged a quick vote on the Senate floor.

President Obama’s former ag secretary was not asked a single question during Tuesday’s hearing about his agency’s troubling mismanagement of civil rights complaints during his long tenure.

In many ways, the friendly tone of the hearing echoed Vilsack’s 2009 confirmation for the same job, which NPR called “more coronation than confirmation.” President Obama’s former ag secretary was not asked a single question during Tuesday’s hearing about his agency’s troubling mismanagement of civil rights complaints during his long tenure.

Vilsack went on the record on topics ranging from trade to nutrition to food aid to biofuels. Over and over, he advocated market-driven and incentives-based approaches to tackling climate change, bolstering the beleaguered dairy industry, and combating the pandemic. The focus on optional, incentive-based changes largely echo the Obama administration’s policies on conservation and environmentally-friendly farming practices, and will likely disappoint environmentalists. Here’s what else you need to know.

On diversity, inclusion, and the agency’s civil rights record: Mostly crickets.

Vilsack was asked just one question on equality and inclusion during the two-and-a-half hour confirmation hearing, and no senator pressed him to account for his civil rights record.

Senator Tina Smith, a Democrat from Minnesota, asked him about the barriers to private farm credit faced by underserved farming communities: “What can USDA do internally and externally to ensure these communities have access to credit options?”

In response, Vilsack said the agency needs to “take a much deeper dive, deeper than has ever been taken before, in terms of USDA programs, to identify what barriers in fact exist in each of these programs,” adding that he anticipated forming an equity commission to begin that process.

On climate change: Incentives, incentives, incentives.

In his opening remarks, Vilsack emphasized that climate change would be among his top priorities as USDA leader. In particular, he stressed that agriculture could play a significant role in mitigating the climate crisis, through programs that financially incentivize farmers to adopt conservation practices like no-till farming and cover cropping that may help soil sequester atmospheric carbon.

“There’s an opportunity for us to create new market incentives for soil health, for carbon sequestration, for methane capture and reuse,” Vilsack said.

But he repeatedly emphasized that any policies aimed at reducing emissions through agriculture would be voluntary, reassuring senators on both sides of the aisle who worried that farmers might face a mandate to adopt climate-friendly techniques.

“It has to be structured and devised and designed in a way in which the principal beneficiaries are farmers.”

“There is a concern that a carbon sequestration bank would potentially benefit investors or third parties,” Vilsack said. “It has to be structured and devised and designed in a way in which the principal beneficiaries are farmers. Why? Because we want them to do this, we want to encourage it, we want to incent it. Why do we want that? Because it’s a quick win in terms of climate change.”

To be clear, the science isn’t completely settled on just how effectively soil carbon sequestration works. Among other unknowns, researchers are still trying to figure out how carbon capture can be measured, and how it should be priced. Vilsack briefly nodded at the need for more research on the subject.

“We need to up our game in research,” he said. “Root systems of crops can be designed in a way to sequester more carbon. We should be exploring that, looking at ways we can increase these for greater storage.”

On nutrition: More support necessary.

The agriculture department isn’t just responsible for supporting farmers. It’s also the Cabinet agency that does the most to feed Americans, and oversees a number of hunger and nutrition assistance programs—many of which have come under scrutiny during the pandemic, as food insecurity has skyrocketed.

Vilsack said he aimed to “get rid of the hassle” that’s associated with applying for nutrition benefits, whether that’s the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or smaller programs, like Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which supports pregnant women and recent mothers. He floated the idea of encouraging states to “create eligibility for a multitude of programs,” rather than requiring individual applications for each.

Vilsack would consider reforming the Farmers to Families Food Box program by awarding contracts to more local farmers and distributors.

Besides more access and “more convenience,” Vilsack also said that “at some point in time, we need to look at the level” of SNAP benefits. He commended President Biden for recently raising the maximum allotment by 15 percent for some recipients for 6 months, but implied that larger benefits would be needed beyond the pandemic. “The reality is that the way in which we calculate that benefit doesn’t make sense today,” he said.

Besides SNAP, Vilsack also signaled an openness to improving some of the beleaguered pandemic assistance programs. He told Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York that USDA needed to give states “more clarity” to operate Pandemic-EBT (P-EBT), a federal program currently available as an alternative to school lunches, and Pat Leahy of Vermont that he would consider reforming the Farmers to Families Food Box program by awarding contracts to more local farmers and distributors.

On the flailing dairy industry: More markets!

Over the last decade, the American dairy industry has been in free-fall. Some critics allege that’s partially Vilsack’s fault. After he left the Obama administration, Vilsack was hired as the chief executive of the U.S. Dairy Export Council, a farmer-funded group that coordinates overseas sales, and represents processors, like the Dairy Farmers of America, that are alleged to drive down prices.

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

The lower prices for milk might work for large dairies that can benefit from economies of scale. That’s less true for small and mid-sized dairies, the ranks of which have thinned dramatically over the last few years. Low prices have devastated that subset while bankrupted dairy farmers unable to make a profit have sold off their herds and even been driven to suicide.

After he left the Obama administration, Vilsack was hired as chief executive of the U.S. Dairy Export Council.

Gillibrand, who has pushed for more government support, suggested to Vilsack that he participate in a “fulsome review” of USDA’s milk price formulas, and specifically incorporate the cost of production in those calculations. Vilsack demurred but said “there are ways in which we can work together to make sure that process provides a better price for farmers, a fairer price that takes into consideration all that’s done with milk,” referring to the value of exports.

Mostly, Vilsack said USDA would help farmers find buyers. He said smaller dairies have “terrific opportunities” in “local and regional markets,” like selling fluid milk to local schools, and suggested that USDA could help by backing farmers who process their own dairy, and thus, could capture more revenues from their own cheese, yogurt, or other products. Vilsack additionally urged “close communication” between USDA and the U.S. Trade Representative to implement existing trade agreements, such as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), that could benefit dairy producers.

On consolidation in the meatpacking industry: A dodge, and a vague promise.

The last time Vilsack led USDA, he faced criticism for delaying regulations that would have given contract farmers greater leverage against meatpacking giants. The department waited until the final months of Obama’s second term before introducing the Farmer Fair Practice rules, which would have made it easier for farmers to sue processors over unfair retaliation. Eventually, the proposal was withdrawn by the Trump administration.

During his hearing, Vilsack didn’t readily agree to reintroduce the rules. Instead he made a vague commitment to “take a close and detailed look at every resource USDA has available to it for more openness and more fairness in our markets.” (Many advocates criticized the rules released at the end of Obama’s second term for doing too little to protect contract farmers, so it’s possible the agency will one day propose a set of rules even stronger than the last.)

“We’ll also take a look at ways in which we can provide incentives or resources that could potentially expand the amount of processing facilities in the country.”

Vilsack also mentioned that USDA could work with the Department of Justice (DOJ) to investigate potential anticompetitive behavior, though he stopped short of specifying which exact sectors he thought deserved greater scrutiny. In June, the DOJ launched an antitrust investigation into the Big Four meatpackers.

On multiple occasions, Vilsack suggested that building more processing facilities would help to prevent the kind of production bottlenecks the country saw last spring. At that time, the pandemic had shut down plants nationwide, leading to huge disparities between what packers pay for live animals and what they charge consumers for meat.

“We’ll also take a look at ways in which we can provide incentives or resources that could potentially expand the amount of processing facilities in the country,” he said. “So that we’re not faced with the disruption we’ve seen in the past.”

On biofuels: More markets!

During President Trump’s tenure, the biofuels industry was often caught playing defense. In one of its last acts, the administration granted waivers to “small” oil refineries, exempting them from a federal requirement to blend plant-based biofuels with gasoline.

In the Biden era, it appears the industry will face a more substantial threat from electric vehicles. General Motors recently announced it will go all-electric by 2035; Biden has signed an executive order encouraging the federal government to purchase only zero-emission vehicles. For senators in corn states, the shift to electric represents a serious concern.

Vilsack, an ethanol booster and former governor of corn-dependent Iowa, struck a conciliatory tone, assuring lawmakers that new markets for biofuels may mature even as personal vehicles shift to electric power. He cited airline fuel and marine fuel as two potential markets.

Vilsack also assured lawmakers that he would push to re-up the Renewable Fuel Standard and sing the praises of biofuels to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “This industry has made great strides in becoming much more environmentally friendly than it was at the beginning,” he said. “Sometimes, I fear we’re still working off old research. New research would suggest that this is an industry that’s providing environmental benefits—cleaner air, for example,” he added.

It’s worth noting that one piece of “new research” Vilsack and multiple senators referenced was a “Harvard-based” study conducted by a Massachusetts-based consulting group alongside Harvard researchers. E&E News reports that the study was commissioned and funded by an ethanol company.