AP Photo/Nati Harnik

Plant workers say there are likely many more cases than have been reported.

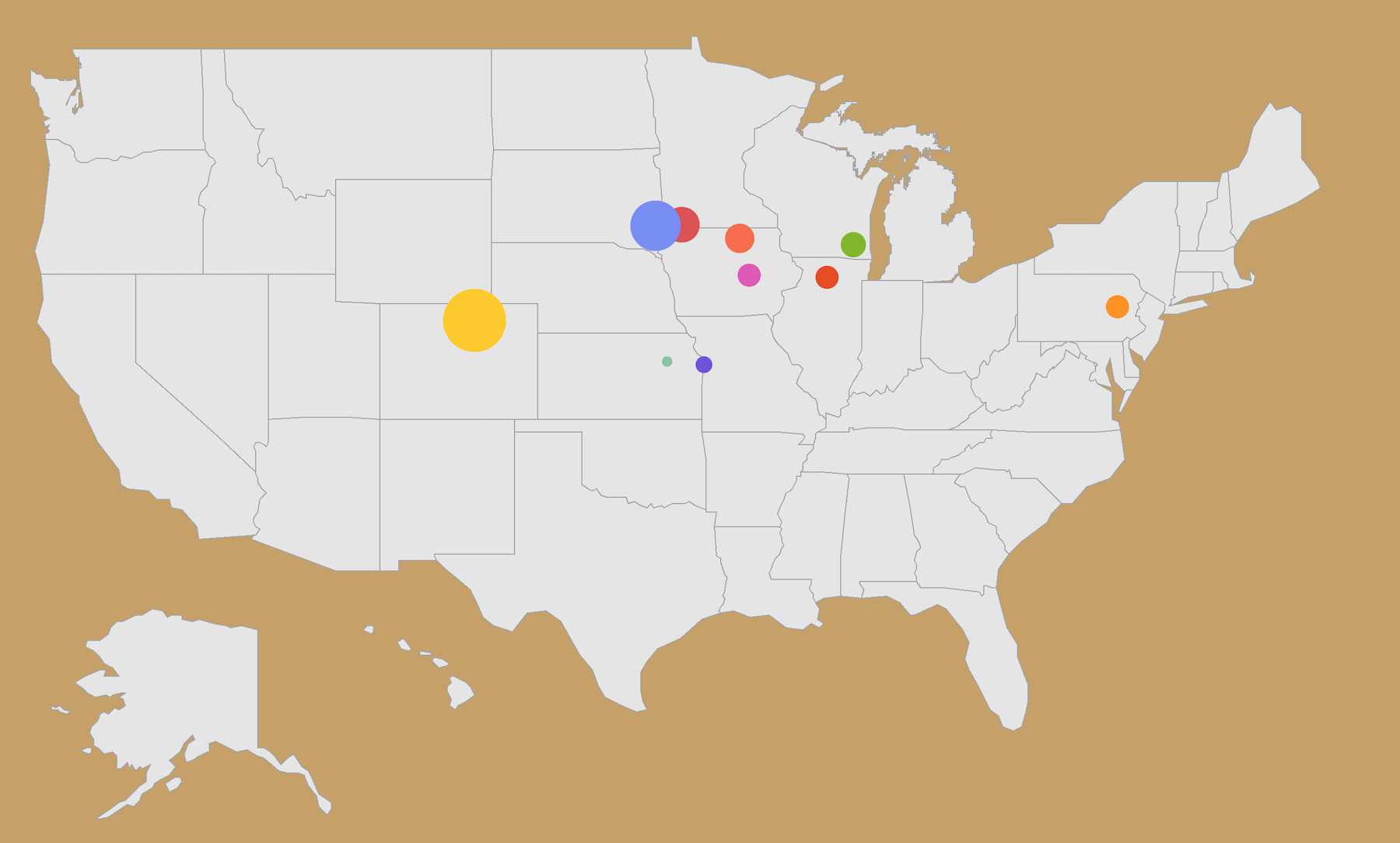

Nearly two weeks ago, Smithfield’s pork plant in Crete, Nebraska, registered its first positive case of Covid-19. By last Friday, the number of workers infected had jumped to more than 20. Then on Monday, after the county conducted robust community testing, that count rose to 47.

And the real number of Covid-19 cases could be much higher, according to Eric Reeder, president of the local United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union, which represents the plant’s employees. Reeder has received numerous calls from workers who report running fevers but haven’t been included in official counts.

A Cargill meat packing plant in Schuyler, Nebraska is pictured above.

In the surrounding Saline County, cases have been increasing dramatically, too. On April 16, there were four confirmed cases. On Monday morning, there were 60. Today, there are 87. These trajectories mirror a concerning trend at meatpacking facilities across the country, at least 20 of which have now shut down due to local coronavirus outbreaks.

“I know there’s other people out there that don’t want to go to work. I know they’re scared.”

“I don’t feel safe,” says Ann*, a worker at Smithfield’s Crete plant. “I don’t want to go to work. And I know there’s other people out there that don’t want to go to work. I know they’re scared. I’m scared.” In an interview last week, she said she feels strongly that Smithfield should shut the plant down for two weeks rather than risk further spread of the virus. On Monday, Smithfield reportedly told Crete employees that it would do just that, but on Tuesday, the company appeared to reverse that stance. In response to a request for comment, it said: “Our Crete, Nebraska, facility remains operational. The company will make an announcement if there are material changes to its operations.”

Workers within meat processing plants attribute the rise in cases to conditions that don’t allow for social distancing and a slow and inequitable distribution of protective gear. In one case, workers didn’t receive masks until last week. In another, managers reportedly received plexiglass shields for their offices weeks before line workers received protection.

Last Friday, more than a month after the coronavirus outbreak was given pandemic status, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued temporary workplace guidance that acknowledged that the set-up of meat processing plants—where workers are required to stand shoulder-to-shoulder for hours—“may contribute substantially to their potential exposures.” The guidance, which is optional, recommends making hand sanitizer available, providing workers with paid sick leave, and spacing them at least six feet apart from one another.

“We’re just a number. They can always replace us with somebody else.”

In response to a request for comment, Smithfield said that it was implementing protective measures including temperature checks, plexiglass barriers between workers, and the provision of masks.

But Ann says that social distancing remains impossible in many areas of the facility, such as hallways, bathrooms, and locker rooms, where hundreds of workers crowd together before and after their shifts, or during breaks. She also says that she’s wary of the accuracy of temperature checks.

“You’re walking clear across the parking lot at 26 degrees,” she says. “How do you check someone’s temperature on their forehead when they’ve been out in the cold?”

Ann says that there’s no contact tracing performed after a worker falls ill and that office workers at the plant have been treated better than those on the slaughter line. Management taped stop signs onto their doors and installed plexiglass around their desks two weeks before she and her colleagues got any protective gear.

“They have little footprints on the floor that say ‘Don’t go no further than that. Stay six feet away,’” she says. “That was put into place before we even got masks handed to us.” (Smithfield did not address the allegations in a request for comment.)

“They’re very hard to breathe in, especially if you have anxiety.”

The mask shortage has been an issue nationwide for weeks. In hospitals, doctors and nurses have reportedly had to reuse N95 respirators, with some state governments forced to bid against each other for personal protective equipment (PPE). Many food processing plant workers have either had to fashion homemade masks out of cloth or go without.

Lee*, a worker at Cargill’s Nebraska City plant, an hour’s drive away from Smithfield’s Crete facility, says that she and her colleagues were not provided masks until last Tuesday. (Cargill did not address the allegation in a request for comment.) However, she’s found that they come with their own problem: “[They’re] very hard to breathe in, especially if you have anxiety.”

Lee believes there’s plenty of room for Cargill to tighten its worker protections, particularly when it comes to communication. That lack of transparency, she says, puts her in the dark about the risk of contracting Covid-19 at work. Out of caution, Lee says that she sprays herself down with Lysol before she re-enters her home every day.

In the past month, meat packers have rang alarm bells, stressing that plant closures would lead to a meat shortage. Smithfield’s CEO said as much a few weeks ago, a prediction echoed by agricultural experts. This past weekend, Tyson took out a full-page advertisement in The New York Times, among other publications, warning of a breakage in the meat supply chain. Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts said last Thursday that he would not order any plants to shut down, citing the importance of maintaining a strong food supply, the Omaha World-Herald reported. He also suggested that the spread of Covid-19 was because of multi-generational households, echoing a Smithfield talking point that places blame for disease spread on the living situations of immigrant communities.

“It may be best to run the plant at half-speed to keep some supply going and separate the workers on the line… so that they’re not elbow to elbow.”

But Reeder, the union president, believes that plants don’t have an either/or choice between production and worker safety. While providing masks and dividers is a good start, Reeder says that plants can still do a lot more to protect employees, such as by conducting contact tracing and isolating all workers potentially exposed to Covid-19, rather than just those who test positive. This may come at the price of reduced production, but that’s arguably better than shutting down a plant altogether.

“It may be best to run the plant at half-speed to keep some supply going and separate the workers on the line … so that they’re not elbow to elbow,” Reeder says. “It wouldn’t be the same production level they have now, but you could … keep the plants running.”

Processing plants are designed to operate at maximum efficiency, which often means moving meat through a plant at dizzyingly fast line speeds. These conditions have been linked to high rates of injury and fatigue; worker and food safety advocates have long called on the Department of Agriculture (USDA) to slow facilities down. However, in recent years, the agency has given processors more leeway to speed up slaughter and evisceration. Since the end of March, USDA has given 16 poultry plants the green light to process chicken faster than ever. After a growing chorus of criticism, it announced last week that it would stop doing so.

One worker at the company’s Milano, Missouri, plant filed a lawsuit against the company under the name “Jane Doe,” alleging that it is failing to protect its employees from Covid-19 risks.

Reeder is also calling on OSHA to issue official instructions to meat processing plants on protecting workers during the pandemic. Right now, the agency has only published the above-mentioned optional guidance, leading to what Eric calls a “hodgepodge” of practices across facilities.

On the flip side, not all food processing workers feel unsafe right now. Vicky Sand is a processing leader at Nestle Purina’s pet food plant in Crete, which is located five miles away from Smithfield’s facility. She says that workers are required to wear masks at all times, and have little trouble keeping six feet apart from each other on the floor.

The specter of Covid-19 still looms in Sand’s mind. A local health official said on Friday that it was too soon to draw a connection between the rise in cases with the Smithfield plant’s operation. But when we spoke last Thursday, Sand said she expected that it was only a matter of time before the virus reached her workplace. After all, many of her coworkers have family who work at Smithfield. A day later, the Nestle plant got its first positive test, the company confirmed in an email.

Meanwhile, at other facilities, a lack of transparency about potential Covid-19 exposures is fomenting fear and anxiety among workers. Last week, one worker at Smithfield’s Milano, Missouri, plant filed a lawsuit against the company under the name “Jane Doe,” alleging that it is failing to protect its employees from Covid-19 risks. It stands to reason that she’s not alone. Last week, OSHA launched an investigation into working conditions during the pandemic at Smithfield’s Cudahy, Wisconsin, plant. Across the industry, according to UFCW, at least 13 workers in the meat and food processing industries have died from Covid-19, while more than 6,500 have tested positive or have missed work waiting for test results.

“[I feel] like we don’t matter, like [Smithfield] doesn’t care about us,” echoed Ann. “We’re just a number. They can always replace us with somebody else.”

*The Counter is withholding some workers’ real names to protect them from retaliation.