FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP via Getty Images

Toxic work environments, poor pay, and difficult customers led staff at restaurants, butcheries, and chain stores across the country to call it quits this year.

In a viral TikTok video posted last month, a customer wandered through the empty kitchen of an International House of Pancakes (IHOP) restaurant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. A bucket filled with what looked like liquid eggs stood unattended on the counter, the ladle still propped inside. Abandoned slices of bacon sat on the griddle. The phone rang, and user @Dj20Grand answered it. “Thank you for calling IHOP,” he said. “Nah, I don’t even work here … Everybody walked the [expletive] out. I’m fixing to start grabbing bacon.”

Similar scenes played out across the country this summer. “We all quit!! CLOSED!!” read a handwritten note posted on a Wendy’s drive-through screen. “Our manager does NOT treat us w/ respect,” said a notice taped to the door of an Arizona Dollar General. And at a Burger King in Nebraska, a marquee-style sign normally dedicated to Whopper specials and 2-for-1 deals read “WE ALL QUIT … SORRY FOR THE INCONVENIENCE.”

There was a certain exuberance about some of these mass-quit episodes, punctuated as they were by exclamation-point lettering. Dirty dishes were left behind like relics while workers climbed ladders to displace burger advertisements with news of their exodus. Photos of the signs ricocheted around social media, no doubt resonating with employees in every sector, who collectively fantasized about walking out mid-shift, co-workers in tow, and leaving someone else to pick up the pieces. Generation X had Office Space, with its iconic, printer-smashing catharsis scene, and that singular moment when Jennifer Aniston, in the role of a server at an aggressively branded fast-casual chain, is berated by her manager for only wearing 15 “pieces of flair,” flips him the bird, and walks out the door.

Workers who quit en masse at a Lincoln, Nebraska Burger King changed the marquee sign.

Rachel Flores/Facebook

This was an Office Space kind of summer. But the stakes are higher: Neither a deadly pandemic nor a change in presidential leadership have advanced a $15 federal minimum wage or paid sick leave policy. Meanwhile, Covid-19 safety protocols for restaurant workers are still up to individual businesses to mandate.

So what happened behind the scenes of the Great Mass Quits of 2021? From dollar stores to craft butcheries, each episode represents an act of collective bravery, a daring decision to choose the unknown over the status quo. But viral memes can also obscure the realities of people who’ve long since been driven to the breaking point and see no option but to exit without notice. For Labor Day, we talked to four workers who quit their jobs this summer—along with many of their colleagues. Here are their stories.

Naderia Wynn

Former server, Del Mar, Washington D.C.

Near the end of her stint as a server at Del Mar in Washington, D.C., the ritzy Spanish restaurant from Italian chef-restaurateur Fabio Trabocchi, Naderia Wynn was sick. Nausea would hit her every time she stepped through her employer’s doors—a culmination, she realized, of months of alleged racism and poor management of social distancing protocols by Stefania Sorrenti, the director of restaurants for Fabio Trabocchi Restaurants, which Wynn said had ultimately hampered her and her co-workers’ pay. The Friday after Wynn left on May 16, nine front-of-house employees followed suit, forcing Del Mar to shutter its doors over the very same weekend that Covid restrictions were being lifted for restaurants. In a letter to management, those who walked out echoed Wynn’s concerns, saying they left “To protest repeated examples of bad practices and bad faith on the part of corporate management at Del Mar.”

My last day was supposed to be on that Friday that everybody walked out. I walked out that [previous] Sunday. I was just like, I’m literally killing myself. I lost 22 pounds in the last three weeks that I was there. I couldn’t actually keep food down. And for what? I’m coming in for $50 a day when we could be making more than that.

I started in September [2020]. Between January and February, they fired all of the management team. All of a sudden there’s this woman, Stefania Sorrenti, who just decided to target me—nitpicking little things. Like, she said something about the color of my hair tie, but my manager was also wearing the same color pink hair tie.

Naderia Wynn said she felt like her job was killing her.

Courtesy of Naderia Wynn

I brought it up to my manager and I’m like, ‘I’m being racially targeted.’ I was the only Black person who worked at Del Mar—the only one out of 75 employees in a city that is called the Chocolate City. I was brought into a meeting with Fabio, and he said Stefania was not going to work with me while they launch[ed] their investigation. At the conclusion of the investigation, they’re like, ‘We’re not firing Stefania, but we’re making her go through anger management and micro-aggression behavior training.’ And I’m like, OK, I’ve heard that line before.

It just went into high gear in about April. [Sorrenti] was packing the amount of covers [diners], even though we only had nine servers on staff. She would start breaking the tables apart. She had a tape measure, and thought she was being really cute by measuring them six feet apart, but you really need a little more clearance because some people sit with their chairs pulled out.

I had already secured another job [at the Michelin-starred restaurant Bresca], prior to putting my notice in, and then my co-workers had been talking about making a statement because some of the things that they [management] were doing were affecting our money. Where once we were making probably close to three grand, we were now making like, twelve hundred dollars every two weeks. It was the [introduction of] tip-pooling, plus when we went to Stefania and were like, ‘You’re not following Covid guidelines,’ they decided to limit covers. One day they had seven of us come in to work the floor and we only had 20 covers. Two of us could have done that easily. We overheard Stefania, many times; she’s like, ‘Well, they wanted safety, now they have safety.’ It was a form of punishment.

I was the only Black person who worked at Del Mar—the only one out of 75 employees in a city that is called the Chocolate City.

I think me leaving moved up the timeline [for the walkout], because they’re like: ‘Well, if one person walks out and then the rest of us walk out after, it’ll drive the point that we’re very serious about this.’ And this is the time to do it: The first day of 100 percent dining with no social distancing—one of the busiest weekends that D.C. is going to have in a very long time. If you’re going to hit them, hit them where it hurts.

Out of the people who decided to walk out, only two were offered their jobs back. One went back because he’s an undocumented worker, so he’s in a different situation than the rest of us. But the other was just like, ‘Are you going to bring everybody else back, including Naderia, and fire Stefania?’ He didn’t go back.

I feel like everybody landed on their feet, which is good. I definitely am trying to make some other moves on my end. Maybe I need to start considering opening up my own coffee retail shop. Something where I can make the rules and I can treat people the way they should be treated.

—

Jade Golden

Former meat monger, Fleishers, New York City

For Jade Golden, a former meat monger who started at Fleishers Craft Butchery’s Upper East Side store in Manhattan this past January, a company-wide walkout was inevitable. On July 22, just weeks after a rapid-fire exodus of management that included the beloved company head butcher, a friend texted the company’s majority shareholder, Rob Rosania, to say that the Black Lives Matter sign at Fleishers’s Westport, Connecticut, location had offended them. Rosania, a wealthy real-estate developer and wine collector, dispatched Fleishers’s new CEO, John Adams, to take down the signage, as well as its pro-LGBTQ sign, even though at least half of the employees identify as BIPOC, nonbinary, or queer. The day after, following Adams’s removal of similar signs in the Park Slope, Brooklyn store, Golden, who is queer and Black, joined dozens of her colleagues in rolling up her knives and walking off the job. Today, all four locations are still listed as temporarily closed.

I got into work at 9 a.m. that Friday. We were opening as we normally do and the store manager got in at 10 a.m., and he hadn’t even put down his bag yet. The phone rang, and the store manager from Park Slope was on the phone to let him know that, basically, things were going to get weird that day.

Golden, who is queer and Black, joined dozens of her colleagues in walking off the job at Fleishers in New York.

Courtesy of Jade Golden

The [shop’s] head butcher and the store manager went downstairs and started this meeting [via Zoom with the CEO and managers from other stores], and it was me and two other mongers upstairs, just talking about what is happening, what this means. The store manager, he had just gotten promoted, after like a year of them asking him to do the job without the payment, the title, and he’s a Black man. I’m a gay Black woman, I’m in a very weird place in my training, and I do not want to start over somewhere else. Like, we don’t want to do this. But we understood it was very, very simple: We either stand with Rob Rosania or we stand with Westport, which had already announced that they were walking out, and Park Slope, which had just said they were walking out, too. So we walked out.

The company used Basecamp as a communication platform between stores and headquarters. There was nothing from the CEO until about 5:50 p.m. on Friday. He sends a picture of one of the locations with the Black Lives Matter sign and LGBT sign back up in the window; a couple hours later, he posts a picture of the Connecticut location with its signs back up. He’s like, ‘I put the sign back up now, so Rob couldn’t retaliate against any of you personally.’ The next afternoon, we get another Basecamp from the CEO telling us that the signs have to come back down, and also: ‘I need you guys to come back Sunday.’

This is not the first time I’ve walked out of a job because somebody did some racist, homophobic, transphobic, misogynistic shit. This is just the first time that, one, it wasn’t my idea, and two, everybody else walked out with me.

We had already stated that we would not be returning back to work, one, without signs, two, until at least Monday, so we have a company-wide call figuring out our unified response. The general vibe was, ‘We are not going back to work for this guy.’ The store manager of the Westport store [said Rosania] made a racist joke to him in the midst of all of this, about how white men can’t jump. The CEO went to the Park Slope location and made a false equivalency between his own BDSM proclivities and LGBT communities. My whole thing the whole time was, ‘I’m here standing in support with you guys.’ After all that was brought to light on Saturday, I was just like, well, now I have my own issues with working for this kind of person. So I officially sent my resignation to HR in the middle of the Zoom call. Everybody had decided they were going to do the same over the next couple of days.

This is not the first time I’ve walked out of a job because somebody did some racist, homophobic, transphobic, misogynistic shit. This is just the first time that, one, it wasn’t my idea, and, two, everybody else walked out with me. It’s fucked up what the CEO and the billionaire investor did, but that I expect. Everybody else’s behavior is just completely baffling to me in the best way possible. It really has made me have a little bit of faith in humanity, honestly. Every butcher shop in New York City reached out to me within like 48 hours and extended discounts, groceries, jobs to me and everybody in the company.

Everybody from the Upper East Side has found new employment as far as I know. While we were sitting there [on Friday], I started posting on Instagram what was happening, like, ‘Oh, I may need a new job, if anybody’s looking for a new butcher, holler.’ The production manager from the Meat Hook follows me and she was like, email these two people. I went on Resume.com, and made a, like, 15-minute resume. By Friday afternoon, I had an interview for Tuesday. Me and the head butcher vibed, I killed my cut test, and I have been employed there full-time ever since.

—

Kayla von Michalofski

Former sous chef, Salare, Seattle, Washington

On a Sunday morning in June, The Seattle Times published a lengthy investigation into multiple accusations of sexual misconduct lodged against renowned local chef Edouardo Jordan by his former employees. The report included accounts of unwanted touching and sexualizing comments that spanned at least seven years, and painted a distressing pattern of alleged misconduct by the decorated restaurateur, who has won two James Beard Awards, among other industry accolades. Within hours of the article’s publication, Kayla von Michalofski, then-sous chef at one of Jordan’s restaurants, and her colleagues began scrambling to organize a mass resignation.

Courtesy of Kayla von Michalofski

After an investigation into sexual misconduct at Salare, von Michalofski and her colleagues scrambled to organize a mass resignation.

In the weeks since, von Michalofski has taken some time off from the restaurant business to reflect on what she called a ‘toxic’ industry, where workers are notoriously underpaid, overextended, and, as ongoing reporting has shown, often subjected to abuse.

Edourardo Jordan called for an emergency staff meeting the Thursday prior to the article’s publication. He said that there was a story coming out that didn’t make him look good, and that he needed to step back for a little bit, kind of leaving all of us managers to fend for ourselves.

Leading up to Sunday, we were talking about what our plan of action was going to be. Once the article came out, we gave everyone an anonymous survey to tell us if they needed to work another two weeks, if they needed the money. But there was unanimous agreement to just quit that day.

One thing that was tough was that our restaurant had a huge event that day that was already paid for. My general manager and I didn’t want to screw the customers over, but it was nerve-wracking to be there when we knew we were going to quit. After we finished, we turned in our keys, our HR representative sent Jordan an email saying that we quit, and that was it.

I was super anxious the entire day. We spent years working for this guy, who we thought was good, and who’s helped me in so many ways, but who wouldn’t own up to it. It kind of felt like I lost a mentor or a friend.

I was surprised by the whole thing, but I can’t support someone with those allegations. I definitely stand with the victims, so that was a pretty easy decision. Quitting with my colleagues made it easier, because no matter what happened, we would all be going through it together. We were super close as a team, so if anyone needed anything, we would have each others’ backs. So I wasn’t nervous about public backlash.

We always knew sexual abuse was a problem, but I didn’t know it was a problem in my workplace.

A couple days after our resignation, everyone who quit got together as a group to talk about our next plans. A bunch of us are doing pop-up restaurants, but I’m not. I need a break from the industry for a couple of months. I had originally planned to go on a road trip in the fall, but I decided to go earlier, because why not? It was definitely needed for my mental health.

I have a few job offers right now. I think I’m going to stay in the food industry but I don’t know what that looks like for me yet. Some ideas include working on a farm where I can grow a lot of my own food, or doing work that supports the community.

We always knew sexual abuse was a problem, but I didn’t know it was a problem in my workplace. I just feel for the victims in this situation, and I’m really happy that they were able to share their story. I hope that more people are able to do the same.

—

Berndt Erikson

Former employee, Dollar General, Eliot, Maine

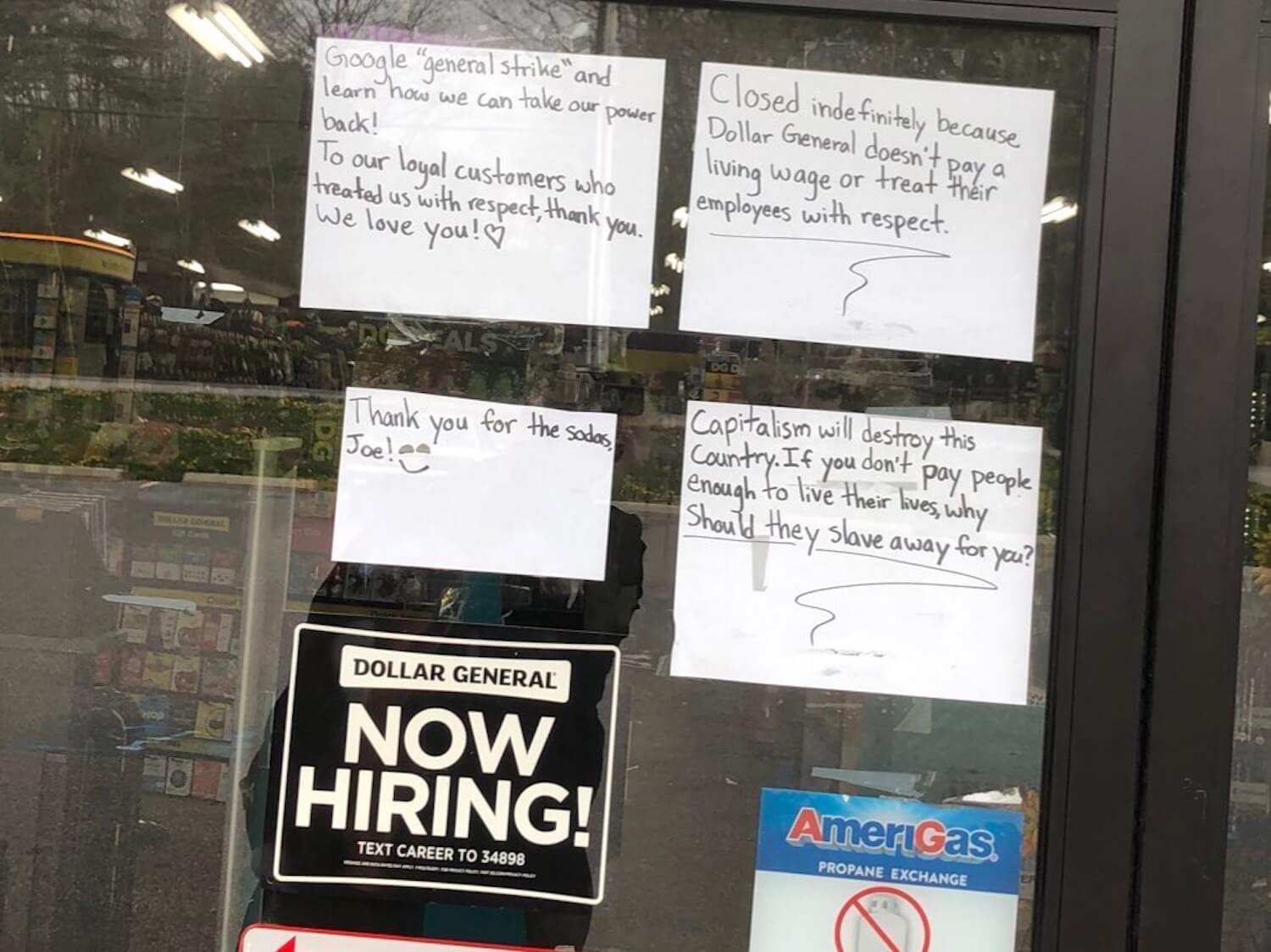

On May 3, Berndt Erikson, then an employee at the Dollar General store in Eliot, Maine, resigned from their job with a splash: On the store’s doors, Erikson and a colleague posted signs publicly taking the company to task for disregarding their well-being. “Dollar General doesn’t pay a living wage or treat their employees with respect,” read one sign. Another took aim at the economic system as a whole: “Capitalism will destroy this country.”

Courtesy of Berndt Erikson

Berndt Erikson was an employee at the Dollar General in Eliot, Maine.

Erikson said their manager had quit the day prior due to burnout, which meant that Erikson’s already heavy workload became even more straining. When company leadership failed to check in on them at any point during their shift, Erikson and their colleague decided to quit on the spot—hence the scathing signs. Erikson woke up the next morning to find that a tweet they’d sent, detailing their move, had gone viral.

Dollar General—a popular retail chain that has rapidly expanded into the grocery business—has been widely criticized by labor advocates for its working conditions: In the last year and a half alone, multiple workers have faced harassment and violence from customers, while enduring low wages and minimal benefits.

In the lead up to my resignation, our store had been understaffed for weeks. We got no communication from upper management on how they would fix that. Then, the day before I quit, my manager quit. I told my company that I would keep working but requested they let me know what was happening.

I came in on my last day with a gas meter of tolerance, and it was already half empty. At that point, it was just a matter of whether they would try to refill my tank: Are they going to reach out to me? Are they going to try to make sure that we’re OK? I just kind of let the meter run empty throughout the day. And by the time I was going on fumes, to keep going with the metaphor, that’s when I pulled out my phone and started to write what we were going to eventually write on the signs. And then, because my co-worker has much better handwriting than I do, I asked her to write it out by hand.

By 4 p.m., when we still hadn’t gotten any contact from management, we put up the signs, called them, and let them know that we were quitting. I gave them my keys the next day.

Signs that Erikson and their colleague left behind after they left Dollar General.

Courtesy of Berndt Erikson

I’m pretty much under the impression that their plan was to have me be the one running the store until they ‘figured something out.’ But I had no faith in them figuring anything out. I figured they were just going to eventually let me settle into a management role, without any promotion or pay increase.

Upper management had made it difficult to work there. There was never outreach or help, only constant negativity and comments about how we were not keeping up with things, how our store didn’t look good enough, how we were not doing things right, how we weren’t keeping up with standards.

The resignation is one of the proudest moments of my life. It was a turning point for me to assert that I deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, and that I was more than willing to make a scene to let someone know. It was a big step.

I made a joke while we were writing our signs that they might go viral. I slept in the next morning because I was letting all that stress come off of me. But I woke up to so many phone calls. I got a lot of amusement out of that experience, but at some point it became wearying to have told my story so many times. Eventually, things started to settle down.

Now, I have a new job and it pays almost double what I was making at Dollar General. My life has significantly improved, not only in that I now have a better job and I can more easily take care of myself, but I also have a confidence that I never had before. I have a self-respect that I’ve never had before. I don’t see myself as someone who is just trying to survive. I see myself as an exploited victim who now needs to fight back.