The Pew Charitable Trusts

In Washington state, the permitting process involves nine different agencies, and is so burdensome and time-consuming that few people bother.

HOOD CANAL, Wash. — On a gray February afternoon, Joth Davis motors his skiff along the northern edge of Hood Canal, a glacier-carved fjord in Puget Sound. A grid of black buoys marks the boundary of his 5-acre saltwater farm, where a crop of sugar kelp is growing quickly beneath the surface and containers of oysters bob atop the waves.

This story was republished from Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts. Read the original story here.

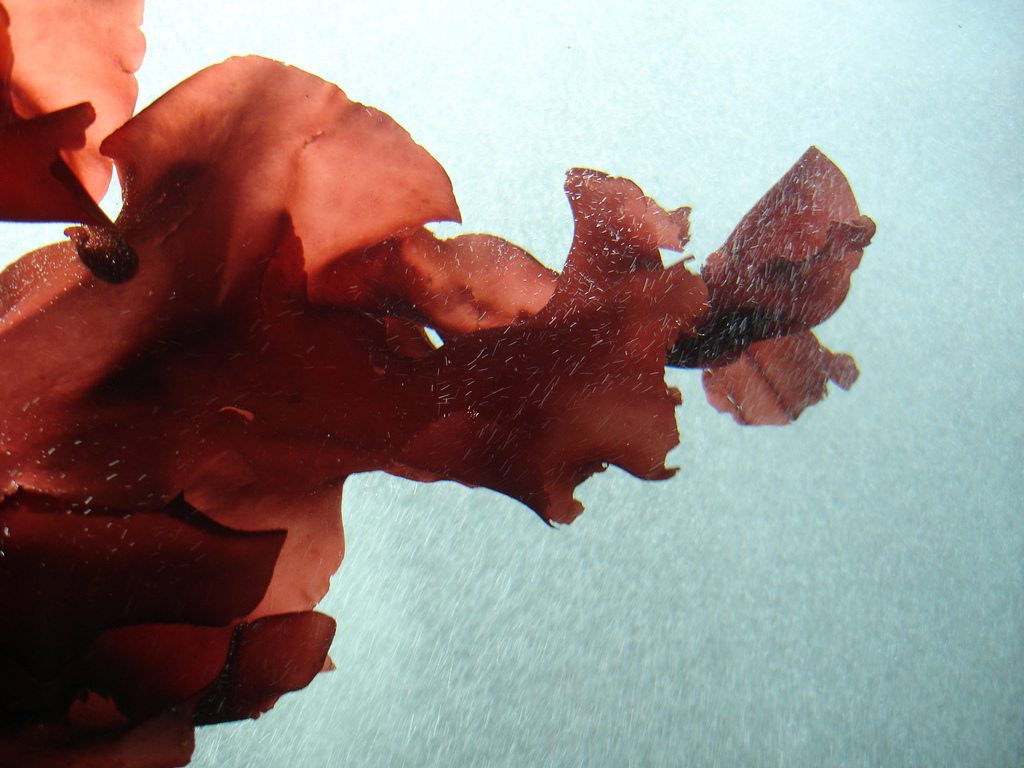

Leaning over the gunwale, Davis pulls up a line dangling thick blades of coppery seaweed. His crop will yield close to 15,000 pounds when harvested in just a few weeks. Davis is one of many who think ocean farming will play a major role in the food systems of the future.

“The economics are wonderful,” Davis said. “Kelp isn’t difficult to grow, and it doesn’t use freshwater or added nutrients. The value proposition is really there.”

Many others want to grow kelp in Washington’s waters, but Davis’ farm for now is the only one operating. The reason is simple: The state’s permitting process involves nine different agencies, and the paperwork is so burdensome and time-consuming that few people bother.

“There’s a lot of people who are interested in seaweed farming, take a look at that [permitting] flowchart, and decide there’s just no functional way,” said Laura Butler, aquaculture coordinator with the Washington State Department of Agriculture.

“There’s a lot of people who are interested in seaweed farming, take a look at that [permitting] flowchart, and decide there’s just no functional way.”

Last week, the Washington House advanced a bill that would create a state strategy for kelp and eelgrass restoration, including research on seaweed aquaculture. The state Senate approved the legislation last month. Davis thinks the bill could promote more ocean farming, but state officials acknowledge that a regulatory overhaul is still needed.

Many coastal states have an equally cumbersome process to administer ocean aquaculture, also known as mariculture. Aquaculture, which involves the cultivation of fish, shellfish and aquatic plants, has been well-established in some states for freshwater species such as catfish and trout. But ocean farming remains a relatively new frontier. Even as proponents see vast potential in farming seaweed and shellfish (and more controversially, net-penned fish such as salmon), would-be farmers face a tangle of red tape.

“We lag behind the rest of the world in aquaculture production,” said Sarah Brenholt, campaign manager with Stronger America Through Seafood, an aquaculture industry group. “One of the reasons for that is the lack of a clear, predictable framework.”

Brenholt’s group has focused its efforts on changing policy for federal waters, which range from 3 to 200 miles from the coast. But in nearshore waters overseen by the states—where much of the industry’s potential lies—the challenges are the same.

The promise of aquaculture

Aquaculture advocates note that America’s consumption of seafood is growing, but most aquaculture products are imported. Research suggests that the nation’s ocean waters have great capacity to support farming operations.

Ocean farmers say their industry offers a sustainable method of food production. Kelp helps to sequester harmful nutrients, while oysters and other shellfish serve as natural water filtration systems. Proponents think farming of fish species can offer consumers protein with far fewer climate emissions than beef and pork production. And the growth of aquaculture could bolster climate resilience, as farms on land face changing weather conditions and scrutiny over their environmental effects.

Workers hoist oyster containers at Blue Dot Sea Farms in Washington’s Hood Canal.

The Pew Charitable Trusts

“[Ocean aquaculture] is nutritious and low-impact,” said Paul Dobbins, who helps lead the aquaculture team at the World Wildlife Fund and has operated both shellfish and kelp farms. “You’re creating food without using arable land, freshwater, fertilizer or pesticides.”

Seaweed also has potential as a fertilizer, animal feed, a packaging replacement for plastics and biofuel.

Supporters say ocean farming can offer economic opportunity to coastal communities that have lost jobs due to declining commercial offshore fisheries.

“We need to figure out how to transition all these people who have these ocean-based skills and culture and traditions of blue-collar innovation to this really important work of climate solutions,” said Bren Smith, a former fisher who now farms seaweed and shellfish in Connecticut.

Smith is a co-founder of GreenWave, a nonprofit that supports aspiring ocean farmers. The group has trained 900 farmers and hatchery technicians, and it has a waiting list of 8,000 prospective farmers who want to join its training program.

Cutting red tape

Some state leaders are seeking to reduce the regulatory roadblocks aquaculture faces.

“The core reason aquaculture is not occurring in our state in any meaningful way is the broken permitting process,” said California Assemblymember Robert Rivas, a Democrat who chairs the Committee on Agriculture.

Rivas has proposed a pilot program that would task state agencies with identifying sites to lease for seaweed and shellfish operations. While the bill stalled last year, Rivas said he remains committed to changing regulations.

Florida created an Aquaculture Use Zone system in the 1990s, with 26 coastal regions in which shellfish farmers can apply for leases with a streamlined permitting process. In Alaska, legislators passed a law last year to speed up the lease renewal process for ocean farmers. The measure’s sponsor, Democratic state Rep. Andi Story, also has worked with regulators to make more staffers available to clear a backlog in lease appeals.

“It’s not a cultural norm to have seaweed on our plates in America, but there would be a big upside if that were to happen here.”

“We’re serious about trying to grow this industry,” she said. “We’re trying to clear regulatory hurdles, because it’s got so much potential.”

Alaska leaders are aiming to grow mariculture into a $100 million industry by 2040. The state’s nascent industry totaled $1.4 million in sales in 2019. They’re hoping to enable more entrepreneurs like Lia Heifetz, who co-founded Barnacle Foods in Juneau in 2016. Her company uses kelp to make products such as salsa and hot sauce.

“We really were motivated to grow a business that could provide a market for kelp farmers and harvesters,” Heifetz said. “It’s not a cultural norm to have seaweed on our plates in America, but there would be a big upside if that were to happen here.”

Lawmakers in New York passed a law last year to allow commercial kelp farming in two Long Island bays, in waters that already had been designated for shellfish operations. Officials are likely to expand ocean farming to more state waters.

“This is an industry that’s in its infant stages, but it has the potential to really transform the marine economies here,” said Assemblymember Fred Thiele, the Democrat who sponsored the measure. Thiele said state leaders likely will need to streamline the permitting process as well.

Many aquaculture leaders cite Maine, which created the nation’s first leasing system for farming in state waters in 1974, as having a well-developed industry and reasonable regulations. The 190 commercial farms in Maine generate $80 million to $100 million annually in sales, led by salmon, mussels and oysters. Many of the state’s new ocean farmers come from commercial fishing or other maritime backgrounds.

Unlike farmers on land, who are limited to private property zoned for agriculture, ocean farmers see vast areas of unclaimed waters with robust growing potential.

The state offers a special limited-purpose permit for new seaweed and shellfish farmers, a one-year lease for a 400-square-foot site. About 750 of those sites are in operation.

“It allows people to start small, to experiment … and limit risks,” said Sebastian Belle, executive director of the Maine Aquaculture Association. “That’s what’s fueling the growth in the state, this lower barrier to entry.”

Several aquaculture advocates said they hope more states will offer a similar small-scale permit for beginning farmers. Ocean farmers also would like to access the benefits available to their land-based counterparts, such as crop insurance and loan programs.

Competition for waters

Unlike farmers on land, who are limited to private property zoned for agriculture, ocean farmers see vast areas of unclaimed waters with robust growing potential. But because their prospective farm sites are in public waters, they must contend with other ocean users, including the military, shipping companies, recreational boaters, commercial and recreational fishers and shorefront property owners.

“The ocean is actually a very busy place,” said Dobbins, with the World Wildlife Fund. “Permitting is never efficient or fast, and there’s good reason for that, because these farms operate in the commons.”

Ocean farmers say their biggest task is building public acceptance. In some areas, wealthy property owners have tried to block farms that alter their views. Farmers and conservationists will have to work out whether aquaculture can coexist in protected marine habitats.

The M.V. Kelp, a floating processing facility, serves the shellfish and seaweed operations at Blue Dot Sea Farms in Washington’s Hood Canal.

The Pew Charitable Trusts

Aquaculture also faces some environmental opposition to the farming of net-penned fish. Opponents point to cases where nonnative fish species have escaped from fish farms, leading to concerns that they could out-compete native fish, spread disease or weaken the gene pool of wild stocks. They also point out the waste from penned-up fish increases nutrient loads in coastal waters.

“If you have regular escapes or large escapes, you’re changing the ecosystem, and we don’t know if that’s repairable,” said Marianne Cufone, founder of the Recirculating Farms Coalition, which promotes the use of recycled water to grow food. Cufone’s land-based farm in Louisiana produces catfish and other species on an aquaponic system, which she said is a more sustainable model.

Supporters of ocean-based fish farming acknowledge there have been some poorly run operations, but they say that better species awareness, improved gear, sustainable feed and smart siting locations can reduce the risk of environmental harm.

‘Let us be the stewards’

Ocean farmers note that many Indigenous peoples have cultivated and harvested coastal resources for millennia. In Hawaii, islanders built distinctive rock-walled fishponds in tidal areas that contributed greatly to local food supplies.

In more recent years, Hawaiians seeking to restore historic ponds found that their cultural practice was now blocked by an overwhelming regulatory system. Locals working to restore one pond site spent 20 years trying to obtain the 17 different permits they needed.

“They had the community support, they had the grants, they had everything, and they just couldn’t get through the process,” said Michael Cain, acting administrator of the state Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands.

In 2011, Cain joined a team of state regulators tasked with streamlining that process, creating a single statewide permit to encompass much of the previous paperwork. Permits now are issued in about 17 days, he said.

“The permitting process was so onerous and expensive that many folks just didn’t want to start,” said Brenda Asuncion, who leads fishpond restoration efforts with Kuaʻāina Ulu ‘Auamo, a community group focused on island ecosystems and culture. “[The changes] have really helped to facilitate people doing restoration work.”

Asuncion’s group has about 60 fishponds in its network in various stages of restoration.

In Alaska, tribal peoples have long used kelp to harvest herring spawn, supplement meals and make nutrient cakes. The Native Conservancy, a Cordova-based, Indigenous-led land conservancy, is aiming to foster 100 Native-owned kelp farms over 2,000 acres of ocean within 10 years.

“Honor the Indigenous people’s right to the land and ocean near them.”

“A lot of people have left the villages because they just can’t make a living,” said Dune Lankard, the group’s president and founder. “We hope this industry will help relocalize individuals that were lost to the seafood industry.”

The Native Conservancy has helped seven private kelp farmers procure permits, and it’s also set up a commercial farm and nine test sites of its own. The group is supporting another 10 farmers who are seeking permits.

Lankard said state officials should give priority to tribes and Native people seeking to restore traditional cultural practices. He cautioned that the fast-growing industry could create another “land rush,” in which large corporations from out of state build massive farms in the waters surrounding Native villages.

“Honor the Indigenous people’s right to the land and ocean near them,” he said. “Let us be the stewards and guardians that we’re capable of being.”