Eliminating this food-poisoning bacterium from poultry is tricky—not least because rapid, precise tests are still unavailable. Researchers are looking at vaccines, probiotics, prebiotics and even essential oils as ways to reduce contamination on the farm.

Every year, food tainted with Salmonella or Campylobacter bacteria causes nearly 3 million illnesses in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among those sickened by Salmonella, 26,500 will be hospitalized and 420 will die, accruing an estimated $365 million in direct medical costs. Though Campylobacter is less likely to lead to hospitalization or death, it’s still no fun, causing diarrhea, vomiting, nausea and, in some cases, long-term health problems. Preschoolers and the elderly are most at risk.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor published by Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.

These pathogens can lurk in many different kinds of foods, but chicken and eggs are major sources. Researchers regularly find Salmonella or Campylobacter on chicken sold at grocery stores, with anywhere from 8 percent to 24 percent of packages testing positive. The law doesn’t ban the sale of raw chicken that’s contaminated like this — instead, it requires manufacturers to test a certain percentage of chicken coming off the production line, and as long as positive tests remain beneath a threshold, production can continue unchanged.

James Provost (CC BY-ND)

Microbiologist Steven C. Ricke University of Wisconsin–Madison

Part of the thinking is that raw chicken — unlike, say, lettuce — gets cooked, killing the microbes. But advocates for change find holes in that reasoning: If it’s so simple, they wonder, why do so many people get sick?

To learn more about the persistence of Salmonella or Campylobacter on poultry, Knowable Magazine spoke with Steven C. Ricke, a microbiologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the author of a 2021 article about poultry safety in the Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What are some of the challenges to eliminating these pathogens on the farm or in the processing facilities?

Campylobacter has an optimal growth temperature of about 42 degrees Celsius, which happens to be the body temperature of chickens. It’s pretty well adapted to poultry. And wild birds are carriers for Salmonella. So are house cats and cockroaches. It can get on the poultry feed when it’s stored. Mice and rats, they love grain. Salmonella can be airborne.

It’s a great survivor — so you can imagine the challenges.

And you can’t look at chickens going through a processing line and say, “There’s Salmonella there.” But sampling itself is a challenge. Ideally, for every product that goes out the door you’d like to be able to immediately run it through some kind of test. Is there any Salmonella there? Campylobacter? If yes, then you take other measures to decontaminate it. Right now, we don’t have tests that are fast enough or precise enough. There’s a lot of research being done, but we’re not there yet.

If we had faster, better and more precise diagnostic tools, other stuff would get easier. For example, in testing control measures, you don’t know how effective the measure was until you have really good diagnostic tools and can ask: How much did we lower the numbers when we applied this treatment?

We also need tools for rapid identification of Salmonella’s different serovars — the traditional typing system for this pathogen that is based on immunological assays. Identifying the serovar is important because not all Salmonella are equal. Salmonella serovars Typhimurium and Enteriditis — these are pathogens of major concern and have been the source of a lot of outbreaks. Other serovars, you would not assign much risk to them. Ideally, you’d have a sensor that would instantly tell you which Salmonella serovar was there and in what kind of amounts.

In your paper, you mention that to fight these pathogens the poultry industry uses probiotics (bacteria thought to be beneficial) and prebiotics (nutrients that promote growth of probiotics). You also mention essential oils. What’s the idea behind these things?

There’s been a growing concern about antibiotic resistance, so the poultry industry has been working to curtail routine antibiotic supplementation. The thing is, antibiotics had a benefit, so now there’s a lot of interest in trying to recoup some of that benefit with these other compounds. Essential oils, probiotics and prebiotics can be added to the feed or water, but they each have a different aim.

Essential oils have antimicrobial properties. They have the potential to kill foodborne pathogens — depending, of course, on the particular compound, the pathogen and the concentration.

Probiotics and prebiotics work, in different ways, to prevent pathogens from establishing in the gut in the first place.

Some people think of these products as more like snake oil.

There’s actually a lot of science behind it. We have worked with essential oils from the citrus industry and they can be very inhibitory towards pathogen growth and survival. In one study, orange oil reduced Salmonella by a detectable number, by a log or two, which in the industry would be important. I wouldn’t say we’ve achieved complete kills of the pathogens, but antibiotics haven’t done that either. Of course, some essential oils are inhibitory and some are not. In a best-case scenario, we want to reduce the pathogens below detection limits.

Probiotics used in the poultry industry include Bacillus, Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus. It’s pretty much what’s in yogurt, but maybe different strains. The aim here is to help establish a healthy gut microbial population.

Prebiotics are non-digestible carbohydrates such as fructo-oligosaccharides, galacto-oligosaccharides and mannan-oligosaccharides. They’re essentially food for the good bacteria. There’s no evidence that I’m aware of that pathogens can use the prebiotics — that’s the beauty. It’s almost like you’re starving out the pathogens and you’re feeding the good bacteria at the same time.

Broiler chickens being reared in a large broiler house in Maryland. Development of better, rapid, accurate tests for Salmonella contamination — especially for the types, or serovars, that are associated with human food poisoning cases — will make it far easier to identify tainted poultry in farm and processing settings. It also will help researchers to assess the effectiveness of control measures such as the use of probiotics and prebiotics.

In a young bird’s first 24 to 48 hours, they’re pretty susceptible because their gut microbes are not well-developed. With probiotics and prebiotics, you can accelerate the development of the young bird’s gut microbes. When you establish a healthy gut microbial population, it serves as a barrier to prevent pathogens from establishing. It’s called competitive exclusion, which is sort of like saying, the neighborhood is already occupied and there’s no way for pathogens to buy a house.

Anything you can do to stack the deck against pathogens and support your good bacteria, that’s a win.

There are groups trying to get the USDA to declare Salmonella an “adulterant” in chicken, meaning contaminated chicken couldn’t be sold. After E. coli O157:H7 was declared an adulterant in beef, illnesses declined substantially. Would that be a good step?

I understand the desire to have it declared an adulterant, but it’s a complex issue. For one thing, you’re dealing with chickens versus cows, two different animal species. Also, Salmonella has quite a bit of range and adaptability. It’s so ubiquitous, I used to say, I could go out and isolate Salmonella from just about anywhere.

On top of that, there are over 2,500 serovars of Salmonella and not all of them make you sick. I think that gets lost in the discussion. In addition, the existence of Salmonella on a carcass is a real imprecise measurement. The question is, how much? If you have one Salmonella on a carcass, the risk of getting sick is essentially nil. But if there were a million Salmonella on the carcass, the risk is much higher. The problem is that we don’t have quantitative tests for Salmonella.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year Salmonella causes 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths in the US. Food is the main source.

We don’t have tests to determine how much Salmonella is in our food?

Well, there are ways to do it, but they’re slow. You want instantaneous results, like the old science-fiction movies where you have the sensor that instantly gives you answers. We don’t have that yet. It takes us potentially at least three or four days to get an answer.

There’s a lot of research being done. We’ve got more rapid tests and we’re getting more and more precise on our quantitation. I think it’s on the horizon.

What’s the most important development you’ve seen in fighting these pathogens?

Whole-genome sequencing has been a game-changer, mostly because it allows you to more accurately pinpoint the source of an outbreak. It’s really revolutionized the science of identification. It’s like the forensic science stuff on these crime shows. The DNA from the person suffering from salmonellosis — can you find that strain in any of the food they ate? Then you go back to the farm and see: Is that same Salmonella there? Or did it get introduced somewhere else in the food supply chain? It allows you to more precisely trace the cause.

Whole-genome sequencing also helps us to understand these pathogens better. For example, because we know the entire genetic code, we can identify which genes make the bacteria virulent. Foodborne Salmonella and Campylobacter typically do not make adult chicken sick. So one fundamental question is, what makes them pathogens in people?

Salmonella contamination has been significantly reduced in some other countries, especially in eggs. Are the challenges somehow more insurmountable in the US? Too expensive? Too inconvenient?

All the above. The places where those pathogens have been effectively eliminated are much smaller countries, with smaller-scale production. For example, they do complete sanitation of trucks bringing feed into the farm. That’s an expensive, extensive process that just wouldn’t be practical here from an economic standpoint.

But there are interventions that would work here. For example, Great Britain went into a very extensive poultry-vaccination process that worked pretty well in eradicating Salmonella in eggs. Vaccines have been employed here, too, but part of the problem is vaccines are somewhat specific. Let’s say you create a vaccine that works on Salmonella Enteritidis. Salmonella Typhimurium can come in and fill that niche, and so now you’re going to have to create a second vaccine. So it’s sort of a moving target. Vaccination programs are very active now and more are being developed as we understand more about Salmonella.

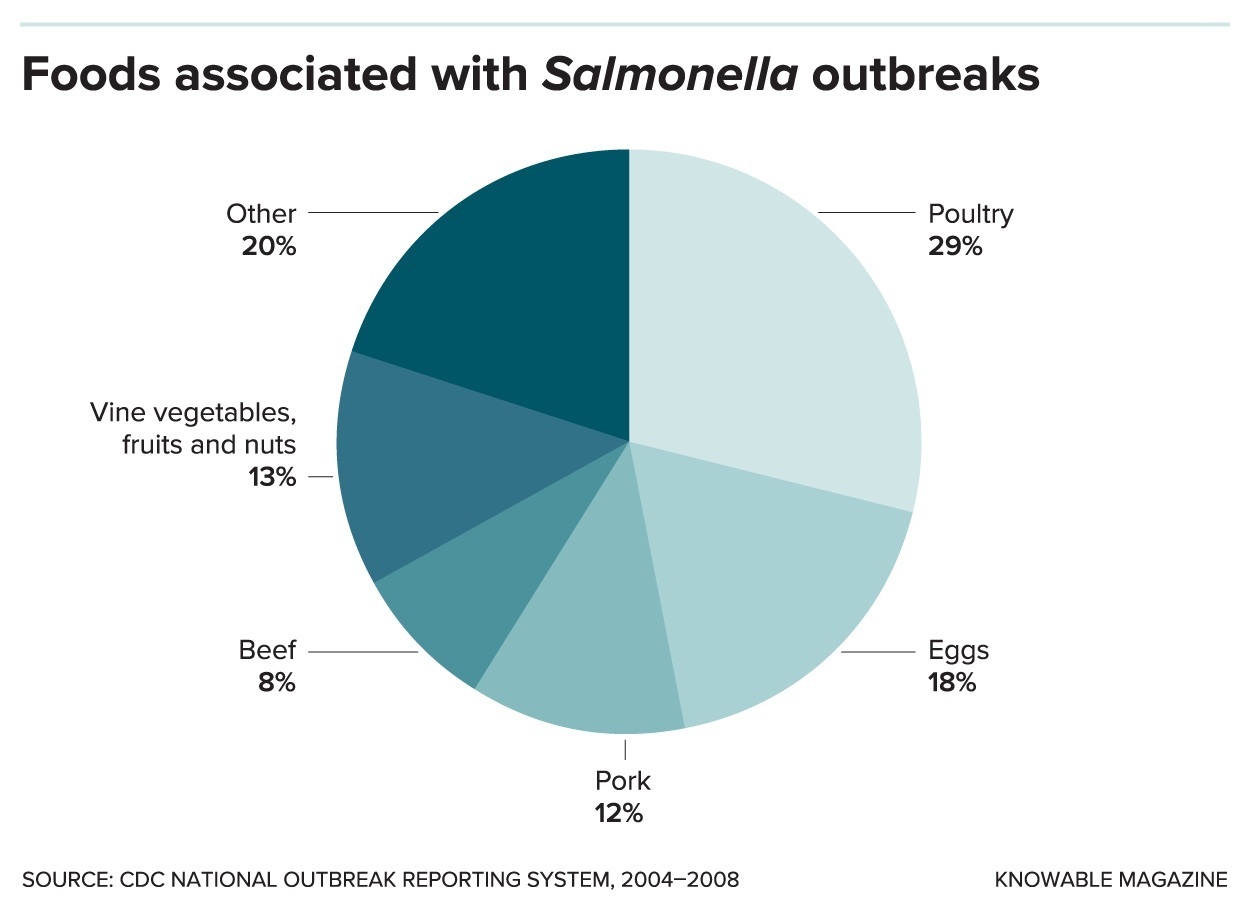

Salmonella can contaminate many types of food. As this pie chart shows, poultry and eggs are hefty contributors.

Knowable Magazine

What else would help?

You want what we call multiple hurdles — several interventions that are very different from each other mechanistically, so they attack the problem differently. We’ve done things like combining mild heat with organic acids, and it’s very effective.

What we really need is more investment, trying to figure out things like which probiotics work best, which combinations work best, so you can get that one-two punch: the probiotic to prevent the establishment of Salmonella and your essential oil to knock out any Salmonella already there. We need more science to do more investigations and to field-test this stuff on real farms and then have good detection and quantitation tools.

Where is the research headed?

Coming up with what I would call mechanistically better-defined interventions to where we know what they’re doing and how they work. Traditionally, producers have relied more on anecdotal reports; we’ve moved beyond that now, and the farmers and companies producing these products know we need peer-reviewed research. We’re in an era that’s exciting for me because I do that kind of mechanism-based research. Now there’s both governmental support and industry support.

What are you working on right now?

We’re doing microbiome mapping of poultry-processing facilities — mapping all the microbes that are found there — trying to identify what we call indicator organisms. These organisms are non-pathogenic, but they behave similarly to the way Salmonella behaves. The idea is they’re usually found in high numbers, and they’re very quantifiable, which makes them easier to detect and measure than Salmonella.

By monitoring these indicator organisms, you can determine whether your interventions are working. If the indicator organism went from, say, 2,000 down to 2, we know that if Salmonella were in there, the measure would work the same way against it.