Ashley Camper

Minnesota distiller Mike Swanson teamed up with researchers at the University of Minnesota Crookston to study whether rye variety determines flavor. Their conclusion: absolutely.

Last August, I traveled to Minnesota to meet Mike Swanson, a distiller and fourth-generation farmer. As we walked into his field, he told me to watch my step—the dried stalks of canola can easily cut into pants or a leg. Swanson was about to plant rye into this stubble because it holds snow that insulates soil from moisture loss and extreme temperatures during the harsh Minnesota winter. The rich, black clay loam was left behind when the glacial Lake Agassiz drained some 8,300 years ago, and the soil was strikingly dark, even though it had not seen rain in quite a while.

Pictured above: Mike Swanson holds a barrel of Far North Spirits whiskey overlooking a field.

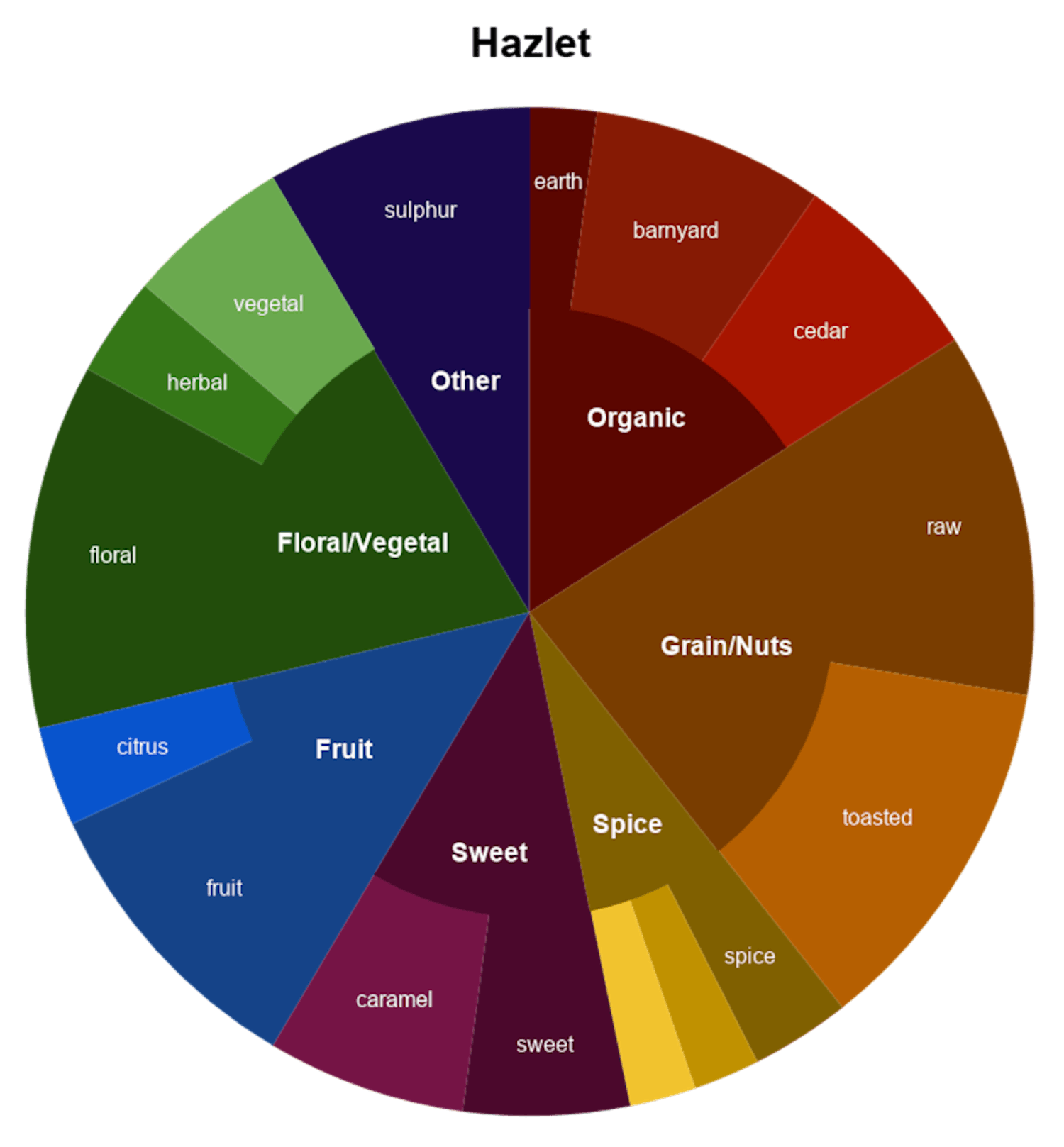

Swanson originally chose to grow AC Hazlet, a Canadian winter rye variety, because of its agronomic characteristics: winter hardiness, resistance to lodging and disease, and yield. Even though these qualities had been well-documented in University of Minnesota and North Dakota State University field trials, there was no information on how Hazlet would taste, much less how it would distill into a whiskey. It was just good luck that Hazlet turned out to contribute the round vanilla and clove notes that have become essential to the house style of rye whiskey that Swanson and his wife, Cheri Reese, produce at 9-year-old Far North Spirits in Hallock, Minnesota.

Though it may seem unremarkable that Far North uses Hazlet because of the flavor it imparts, it’s unusual to find whiskey producers focused on rye varietals. In fact, the conventional industry wisdom has long held that differences in variety or where the grains are grown have little to no effect on the final product. The idea is that the distilling process strips out the subtle flavors that a particular variety (or a particular terroir) might offer.

AC Hazlet is a Canadian winter rye variety, because of its agronomic characteristics: winter hardiness, resistance to lodging and disease, and yield.

Megan Sugden

But Swanson had grown and distilled Hazlet for several years before he considered the possibility that other varietals might provide flavors distinct from those he was getting from Hazlet. It was a 2014 call from a Maine farmer who had been growing rye for some local distillers that got Swanson thinking about other varietals. This rye producer said that distillers had complained about the pronounced pepper spice they were getting from rye categorized as VNS (“variety not stated”) by grain merchants. He had heard about the vanilla notes Swanson was getting from his Hazlet rye and had set out to get some for himself. However, the producer had not been able to find the seed anywhere east of Saskatchewan, so he asked if Swanson would sell him some. Swanson did, and thus started his deeper dive into the relationship between rye varietals and flavor—with the help of researchers from the University of Minnesota Crookston.

The vast majority of commodity rye grain is sold as VNS rye. The same is largely true of the rye seed farmers buy, though there is a bit more specificity of variety on the seed side. There are many factors behind the prevalence of VNS rye, but an important one is that many farmers grow rye only as a cover crop. But another significant reason is that rye is a cross-pollinator that can shift genetic—and thus varietal—characteristics in just a generation or two, which makes it difficult to maintain one variety’s purity over time.

Unlike most rye whiskey producers, Swanson grows all the grain he distills, and he had come to believe that the variety of rye he had chosen was more important than conventional wisdom recognized. Swanson wasn’t the only one: A few other distillers in the U.S. were also making whiskey from specific rye varietals, so he set out to test the proposition that variety affects flavor.

“With a varietal, I can talk about how I make my whiskey out of what grows well here. And this is going to be different than what grows well in Georgia or somewhere else.”

In 2015 Swanson asked Jochum Wiersma, a small grains specialist at the University of Minnesota Crookston, if there was any scientific research into how variety influences flavor, particularly in rye whiskey production. The answer, a literature review suggested, was no. So together, they applied for and won a crop research grant from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture to start the process of finding out. Despite what Swanson had already gleaned from distilling different varieties of rye, he knew an outcome showing that variety does not influence flavor would be a valid scientific result, even a welcome one.

“That would be good news for farmers,” Swanson said, “because then they could grow whatever rye grows best for them, and good for distillers, because the flavor of the ultimate spirit would then be mostly about their skill and not the exact character of their ingredients.”

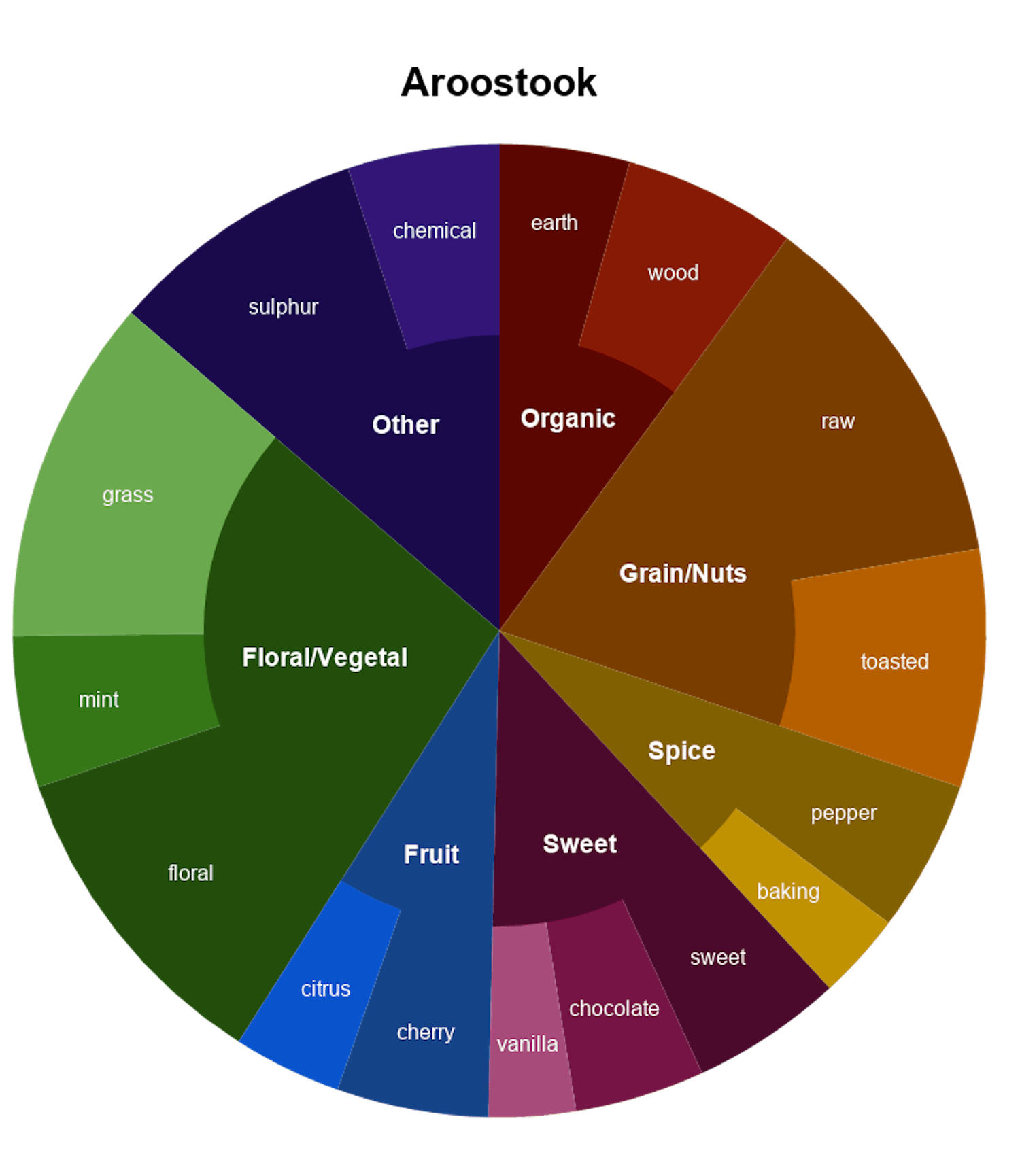

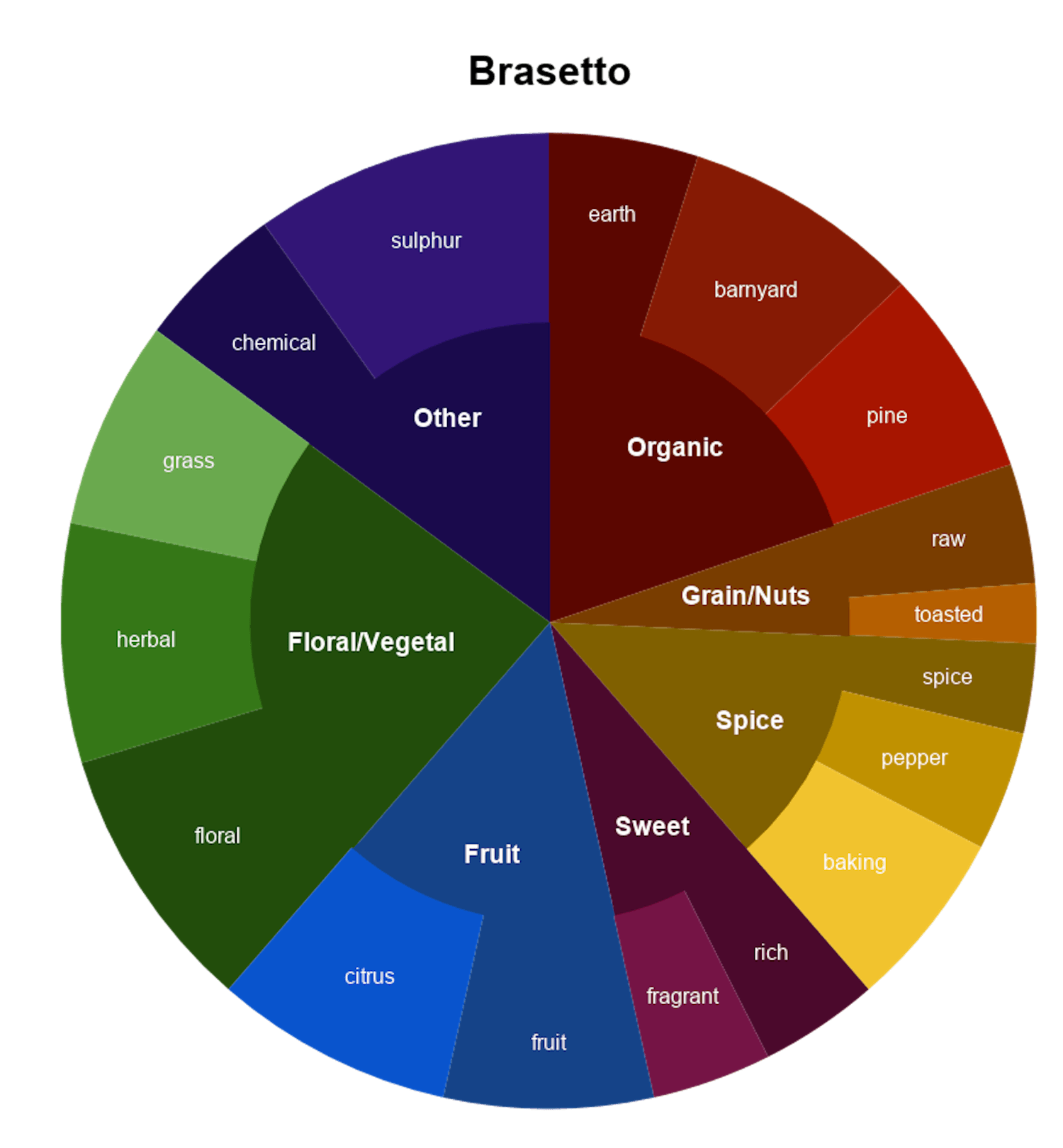

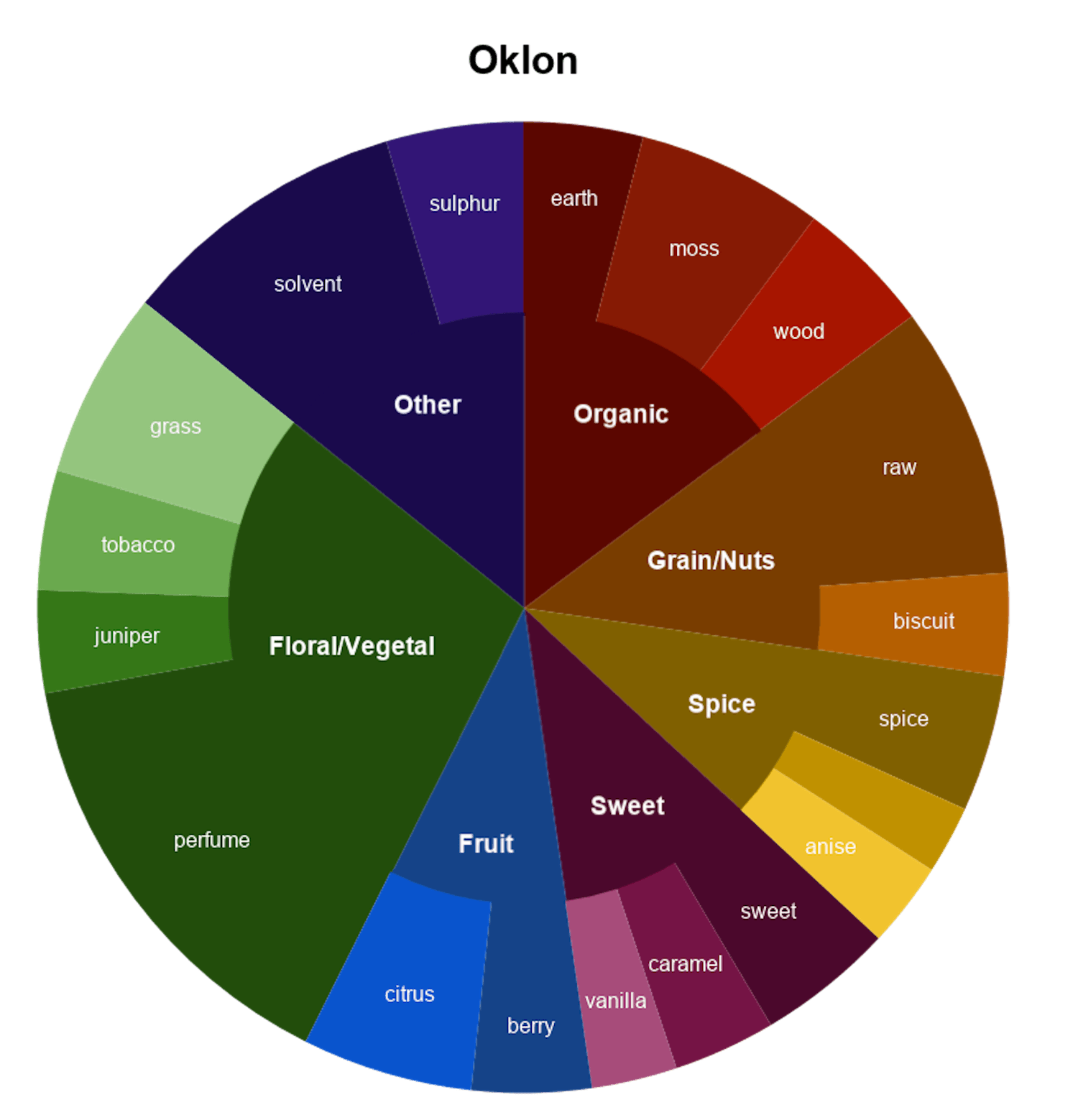

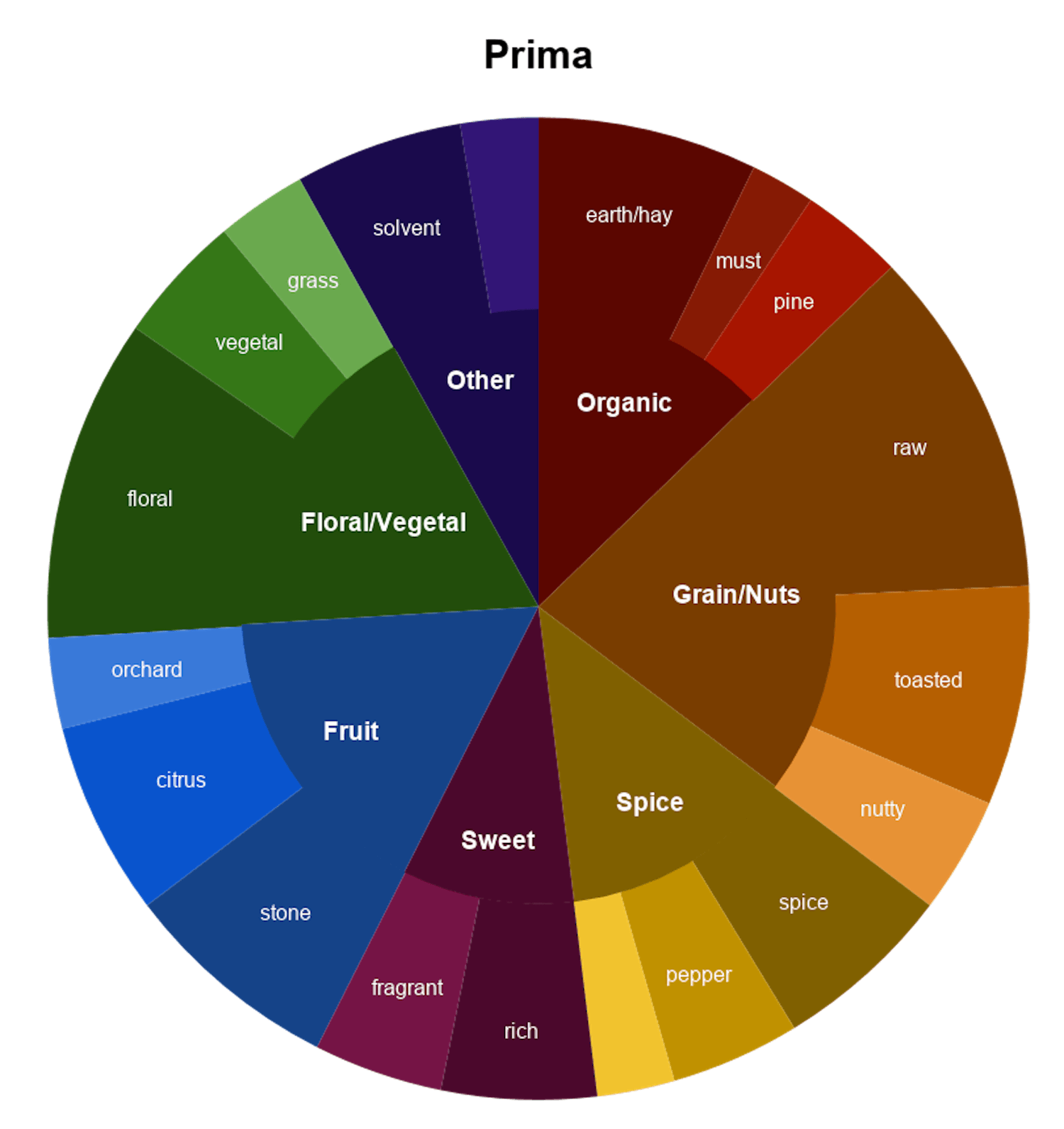

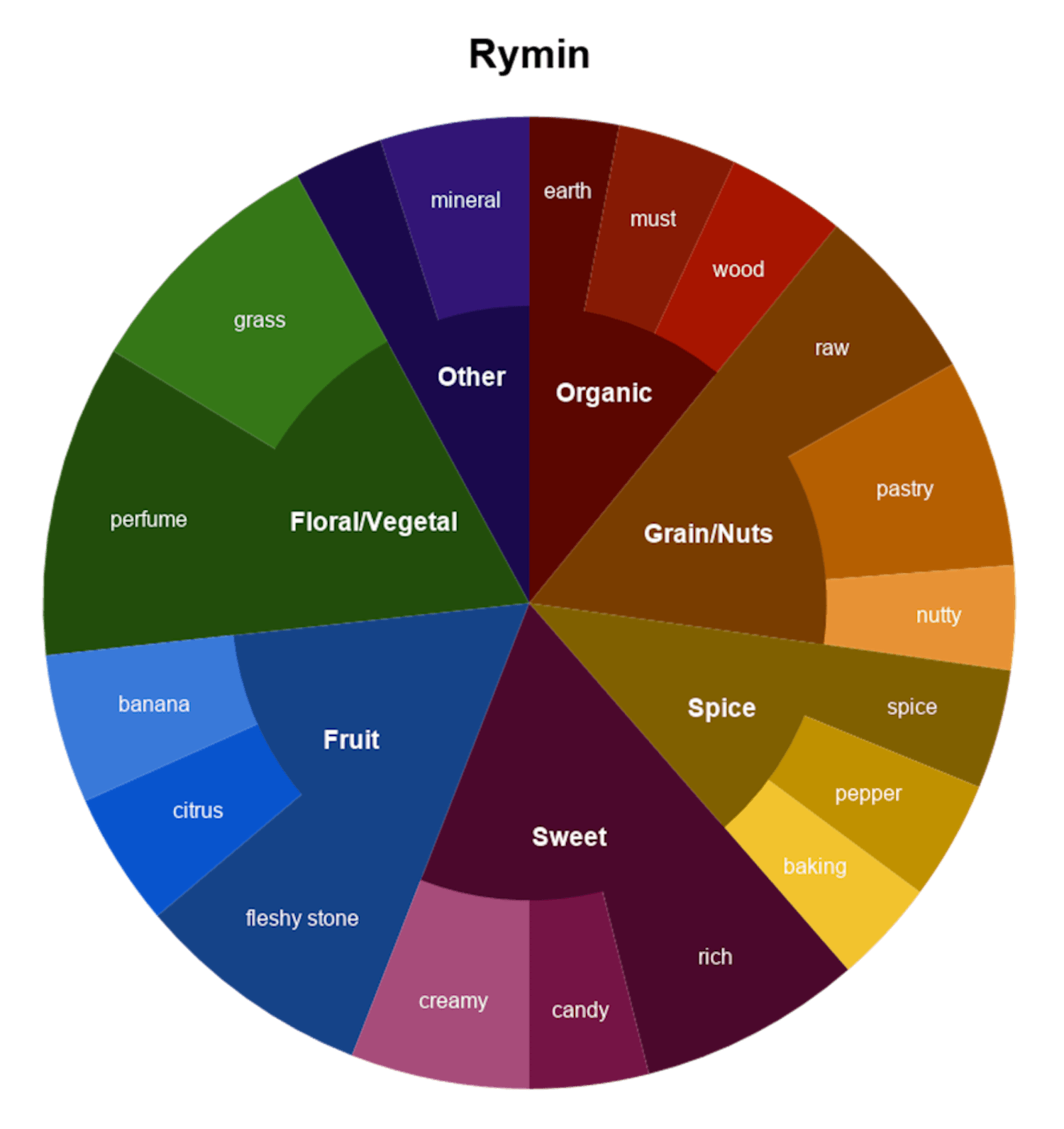

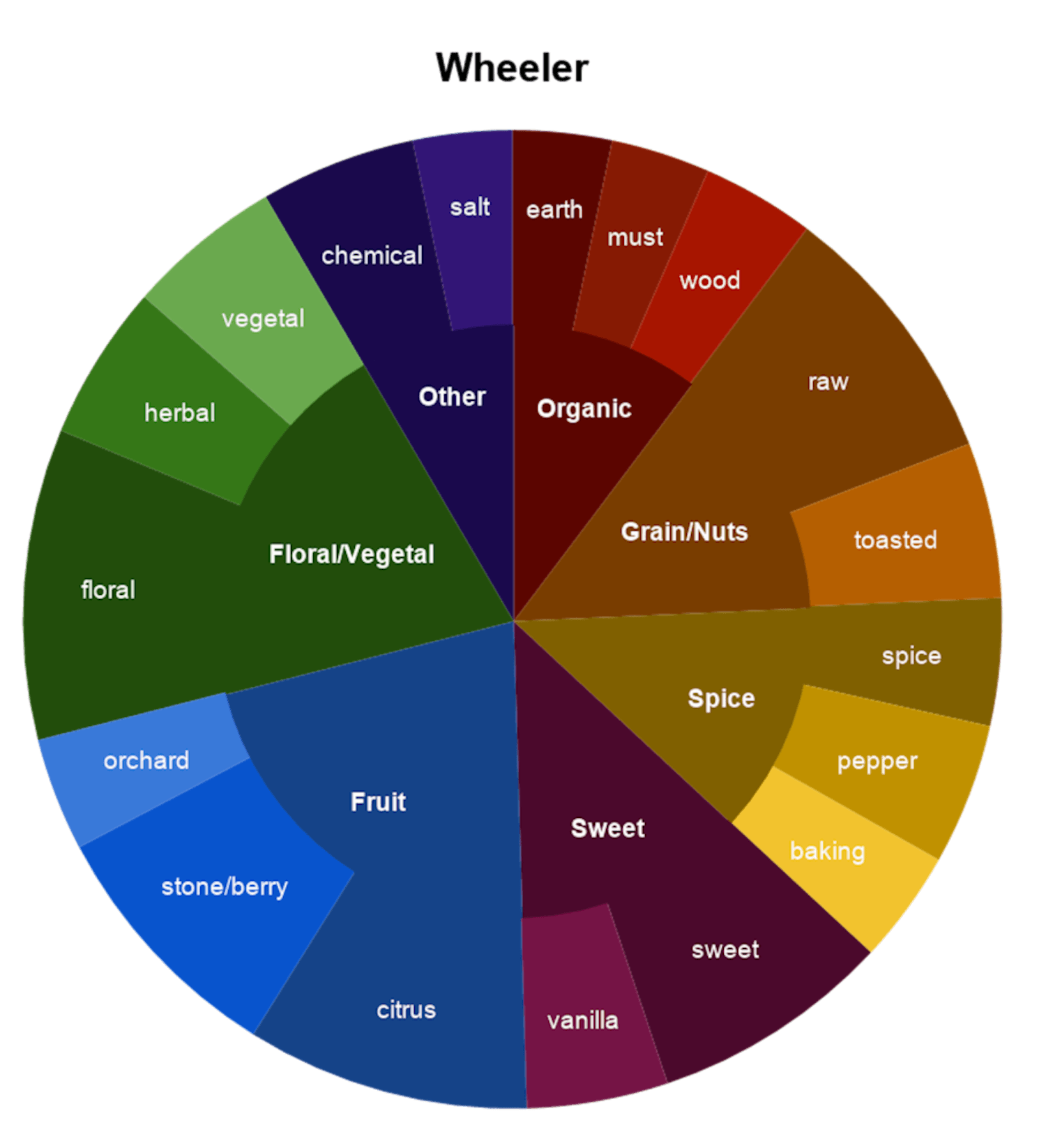

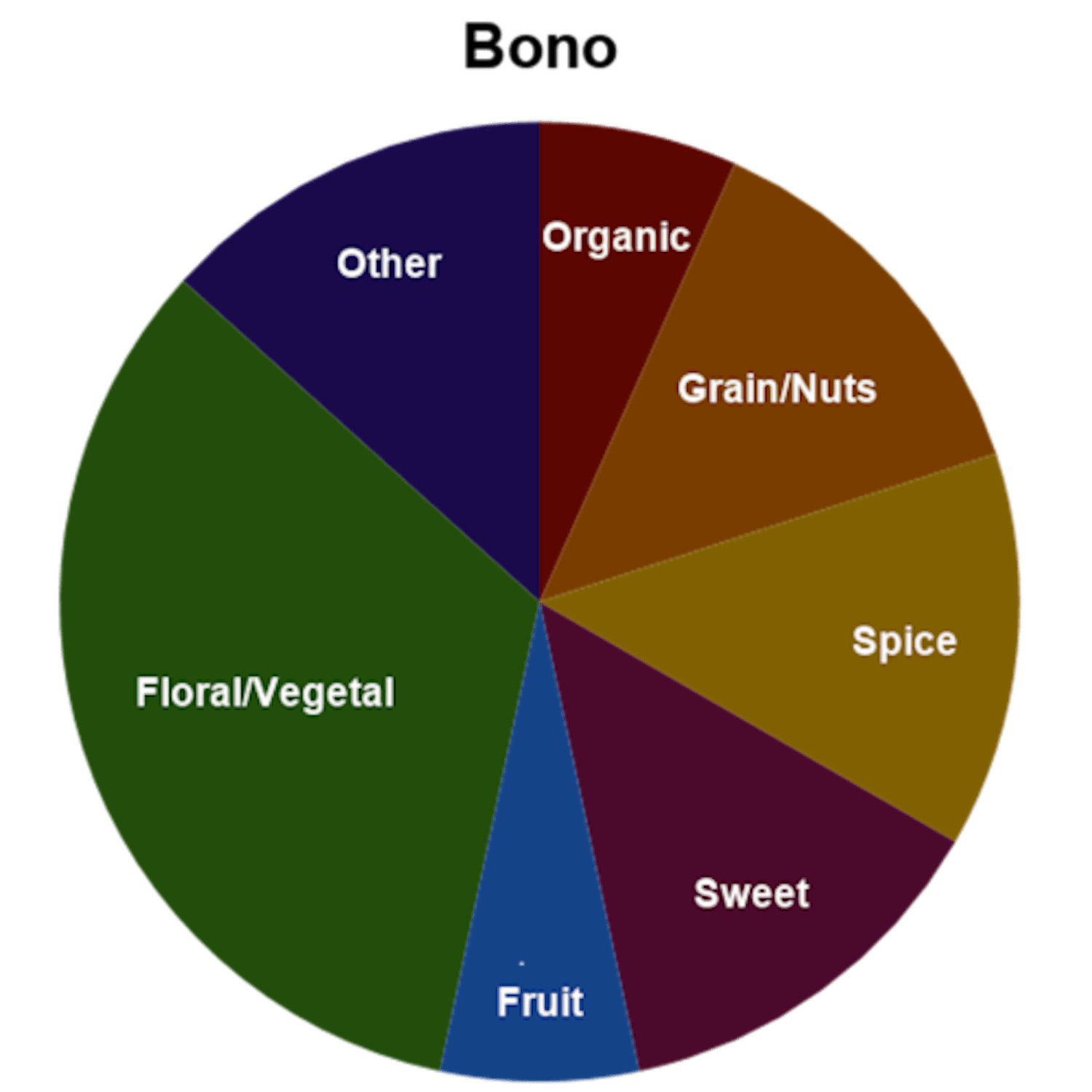

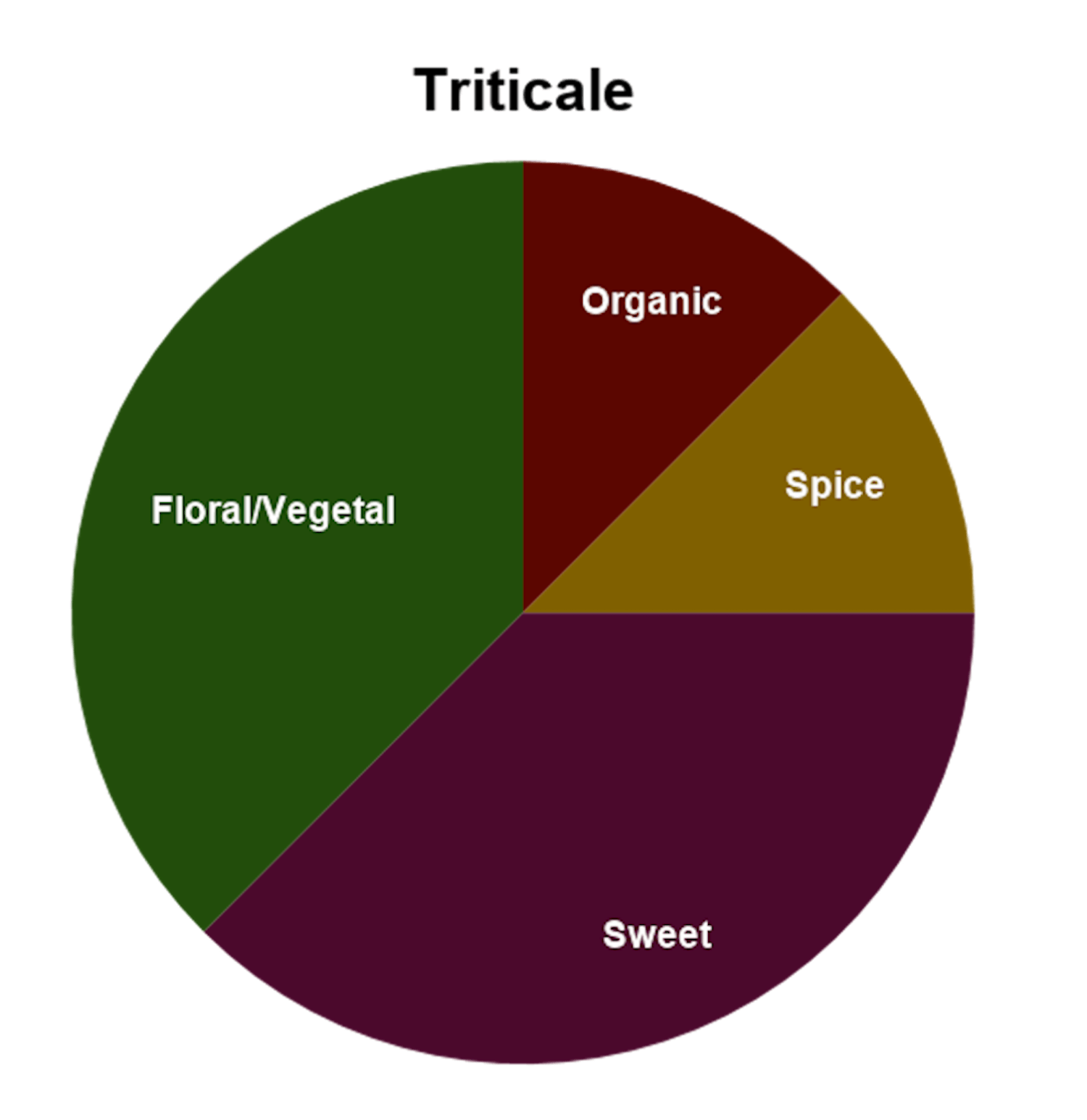

Researchers at the University of Minnesota Crookston examined the flavor profiles of whiskeys produced from 15 different winter rye varietals. In the study, 190 participants (a mix of industry experts and laypeople) smelled and tasted the unaged distillates—or “white whiskey”—and provided descriptive feedback for each of them. The results, portrayed as flavor wheels with larger sections representing greater frequency of that descriptor, demonstrated significant differences between varieties, with tasters sharing common flavor notes for each variety. Some, like Arostook, Brasetto, Oklon, and Bono, offered pronounced floral notes, while others, like Rymin, Spooner, Dylan, and Wheeler, leaned more sweet- and fruit-forward in their profiles. The frequency of grainy and spicy notes also varied noticeably across varieties. And some varieties clearly yielded more “off” notes—sulphur, solvent, chemical—than others.

Winter rye varietals of whiskey flavor wheels produced by researchers at the University of Minnesota Crookston

Five varieties received fewer responses, so their flavor wheels feature less detail:

Wiersma pointed out several shortcomings of the study, like the fact that it featured neither replicated grow-outs (growing particular varietals more than once) nor replicated batches (making whiskey batches with each varietal more than once). Instead, over the three years of the study, each year featured a distinct set of five or six varietals grown in one-acre test plots, meaning some varietals were grown in different seasons. And with only one-acre plots for each varietal, some of which yielded much less than others, there wasn’t enough of some varieties to make more than one batch of whiskey. But Wiersma added, “To me, the study is really a first foray into the question: Does variety matter?”

Despite the study’s limitations, Wiersma said the results point clearly in one direction: The flavor differences between types of rye in the study are so vast that they are most likely varietal rather than seasonal. Since Swanson grew all of the plots on his own land, the differences could not be attributed to location. Production techniques were also consistent across varieties, as Swanson used the same enzymes and mashing process for each, and ran them all through the same single-pass distillation process.

Mike Swanson

Swanson released a number of the whiskeys, each aged 18 months in 15-gallon barrels, to different markets under Far North’s “Seed Vault Series,” so consumers can taste the variety for themselves.

Beyond the headline result, the study also found that the hybrids (a cross of two different varieties) offered a narrower range of flavors than the open-pollinated varieties (a single variety sharing the same parent plant, including heirlooms). This was not particularly surprising, given that open-pollinated ryes feature more diversity, even within a single field, including in stalk height and grain size, than hybrids do. More surprising, however, was the fact that aging the various whiskeys in oak barrels seemed to accentuate, rather than smooth over, many of the flavor differences in the unaged whiskeys. Though the study did not fully examine how each of the whiskeys tasted after aging, Swanson has released a number of these whiskeys, each aged 18 months in 15-gallon barrels, to different markets under Far North’s “Seed Vault Series,” so consumers can taste for themselves.

Swanson sees promise for craft distillers in the study’s results: “With a varietal, I can talk about how I make my whiskey out of what grows well here. And this is going to be different than what grows well in Georgia or somewhere else. That’s one of the biggest things that craft distillers can offer the marketplace: regional expressions of spirits. Like they do in Scotland.”

However, making it attractive for other farmers to grow varietal rye is not without its challenges. Even though distillers will pay anywhere from two to five times more per bushel for certain varietal ryes than the commodity system will pay for VNS rye, most farmers are not connected to distillers or other customers looking for specific varieties. And many farmers are used to thinking about rye only as a crop for use in rotations, since it is not normally a “cash crop,” even when prices are high.

The Hazlet variety contributed to the round, vanilla and clove notes that have become essential to the house style of rye whiskey that Mike Swanson and his wife, Cheri Reese, produce at 9-year-old Far North Spirits in Hallock, Minnesota.

Stephen Mathis

Jeremy Wilson, a farmer in Jamestown, North Dakota, whose approach centers on no-till techniques, grows rye both as a cover crop and for harvest, but his main focus is on what rye does for his soil. “One of my biggest uses of rye is before soybeans, because I can plant soybeans right into rye, and they don’t mind the rye being there at all,” he said. “Rye has an allelopathic effect in its roots where it doesn’t allow other weeds or plants to grow. And we use that to our advantage: We’ll plant a good stand of rye, then we have less dependence on herbicides for some of our other crops. So rye’s kind of my buddy.”

Another challenge is that many of the open-pollinating varieties, especially those sought after as “heritage grains,” not only yield less than the hybrids, but many also add layers of difficulty by requiring particular spraying schedules or special harvesting techniques. Laura Fields, CEO of the Delaware Valley Fields Foundation and the driving force behind the Seed Spark Project, which aims to restore long-lost heritage grains, has been working to bring the varietal Rosen rye back to Pennsylvania (Michter’s, back when it was a Pennsylvania distillery, touted the ingredient for a number of years on its labels). One farmer she worked with, Wesley Kline, did not find growing Rosen too challenging once Fields laid out the steps he should follow and their timing. But some of the steps were new to him, like applying a growth inhibitor early on to help keep the notoriously tall Rosen rye plants (which normally reach six feet in height) from falling over. And harvesting such a tall plant caused some issues: “It’s a lot slower harvesting,” Klein said, “because of the length of the straw. And it was also laying down, so it took longer.” Klein had a good experience growing Rosen and got a great yield and a high price for his crop, but is ambivalent about growing more. “I’m not sure yet,” he said. “We want to grow it a second time [on the same small plot they used last year] to see.”

There are also questions about how best to establish sustainable markets for varietal ryes. Wiersma, for example, notes that unless a big producer decides to use varietals, the demand for such ryes faces one significant barrier: “You don’t need a lot to make a hell of a lot of whiskey. Two quarters, or 320 acres, for a farmer isn’t that much. But for Mike, it’s enough to last him a decade. We can’t drink our way out of that problem.”

But varietal advocates like Fields are working to address this problem of scale directly. Fields and the Seed Spark Project are connecting farmers to a growing stable of distillers to produce Rosen directly for them. The goal is a farming cooperative that provides Rosen rye in such a way that no particular bad crop leaves distillers without grain. But scaling up too quickly can undercut the premium farmers can currently get for Rosen. “I want to make sure that we’re satisfying all of the needs without overproducing, and having money lost, because this is a very expensive grain to grow right now,” Fields said. “So it’s a balancing act.”