Jonah Miller

For reasons of safety and cost, many restaurant owners are abandoning traditional handheld menus. Will QR codes become the new normal?

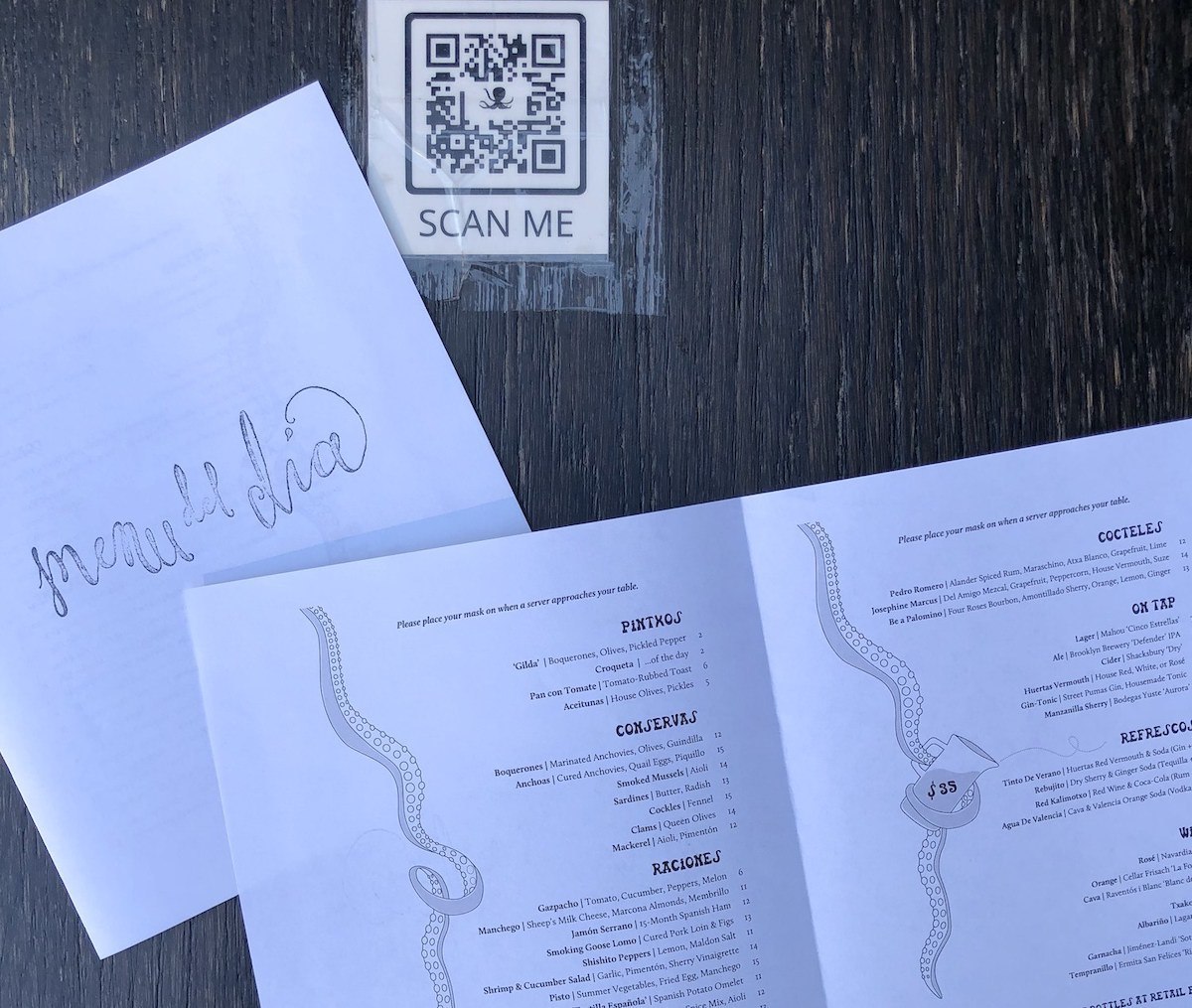

When people dine outside at Huertas, my restaurant in New York City’s East Village, this is how the host greets them.

“Hi,” with a smile. “So, we are doing table service, but in order to reduce contact and trips through the bike lane, we are encouraging guests to place an order for a first round of drinks and food here at the window, and the remainder of your order can be placed while seated. There are QR codes on the table, just like this one next to me, which pull up our menu. Please do keep your mask on when the server is at your table, especially while you’re speaking to them. Lastly, because we have so few tables, we are asking that guests limit their stay with us to an hour-and-a-half.”

It goes on a bit from there. We take their order and then pass them glasses and a bottle of water and point them to their table so they can seat themselves.

Guests who outdoor dine at Huertas, a restaurant in Manhattan’s East Village can order from the QR codes on their tables.

Jonah Miller

Menus may not be a big deal in terms of everything restaurants face during the pandemic, but they sit at the crossroads of safety and sentiment, so any change matters on multiple levels. The CDC offers blunt advice: “Avoid using or sharing items that are reusable, such as menus,” and “Instead, use disposable or digital menus,” a shift that impacts not only sit-down restaurants but quick-serve places that rely on menu-boards. Local health departments chime in with their own advice and regulations.

The days of people lingering over a menu, whether at their table or in front of the restaurant, are over, and it’s a harder transition than some because it sets the stage for the rest of the meal. My colleagues and I are left with a complicated set of choices: How do we keep our diners safe without abandoning the first act of the evening’s show?

Wilson Tang, owner of Nom Wah Tea Parlor, the oldest continually operating dim sum restaurant in Manhattan’s Chinatown, finds himself at an odd crossroads: While other countries have long since abandoned paper menus, the tradition of checking off items on a paper list is still a popular part of the experience. His flagship Chinatown operation uses a hybrid solution: There’s a QR, or quick-response code, that displays the menu when a diner points a smart phone camera at the barcode, but guests still receive a single-use paper menu to mark their selections.

“You can sit down, not talk to anyone, scan the QR code, the food shows up, when you’re done you scan it again, pay, and you can just walk away. Obviously, it’s the most safe—it’s fully contactless.”

“We’re actually, as a country, way behind in technology,” said Tang, who operates two locations in Shenzhen, China. “There, basically every table has a QR code and once you scan the QR code, the code will pull up an app and you do the ordering on the app and it’s all integrated—you even pay on the app. You can sit down, not talk to anyone, scan the QR code, the food shows up, when you’re done you scan it again, pay, and you can just walk away. Obviously, it’s the most safe—it’s fully contactless.”

But customer preference is a variable in the safety equation; since people here are used to paper and pencil, Tang opted for a solution that keeps them safe but preserves a bit of what is now the past.

Vic’s, in the NoHo neighborhood of Manhattan, was among the first wave of restaurants to open for outdoor dining in June under New York City’s “Open Streets” program, and quickly implemented QR codes. They encountered some initial resistance from guests who “didn’t really understand—the phone, the picture, the code,” said executive chef and partner, Hillary Sterling, but the vast majority adapted immediately. About 10 percent continued to balk, so the staff was instructed to let them know, “It’s okay if you want a paper menu,” said Sterling, “but please, we’re not going to take that back.”

We don’t include photos at Huertas, but it’s a popular feature of many quick-service menus.

Jonah Miller

Table QR codes take guests directly to Huertas’ online menu.

QR menus have their advantages, once you get used to them. Joshua Stern co-founded Wine n Dine in 2015 to build visual menus and improve restaurants’ online presence, and he encourages restaurants to add photos to their digital menus because they “increase the amount of food people order, which is why delivery companies have been pushing restaurants to do this for years.” We don’t include photos at Huertas, but it’s a popular feature of many quick-service menus.

And digital menus liberate a chef—from hesitating about introducing a new dish that requires a menu overhaul, and from having to disappoint diners when a dish runs out. There are no reprint costs, as there are with paper menus.

As a young sous chef, I was taught never to eliminate an item; better to reprint menus before service than inform a guest, tableside, that what they wanted wasn’t available. With a QR menu, we may someday be able to update listings in real time: when you sell the last bottle of Burgundy or final slice of pie, it automatically disappears from the menu. Changing your menu at no cost, with no waste, can be a game-changer: At Vic’s, pre-pandemic they printed over 200 menus a day (at a cost of roughly $375 a month), and now they’re down to 20, solely for guests who ask for them.

“People eat with their eyes, not with words.”

But digital menus only work if guests embrace the idea. JJ Johnson, the chef-owner of Fieldtrip, in Harlem, intended to use them when he opened just over a year ago, before safety was even an issue. “I had a big decal in the front of the store window that said ‘scan your phone for a digital menu,’ and nobody would. We’d say ‘Hey, we don’t do printed menus, just use the barcode, scan your menu,’ and they’d say, ‘Oh, you’re pretentious’ and all this stuff. So I took it down and went to paper menus.”

He tried having them printed offsite, at $1 per menu, but found that they quickly got dirty and had to be discarded, so he simplified the design and got the cost down to 15 cents apiece. Once the pandemic hit, he switched to printing in-house and having the menus laminated at the UPS store across the street. And he reintroduced a digital option.

People are less resistant to digital menus now, and I think it’s for three main reasons: they’re contactless, they represent environmental and financial savings, and they provide visuals. “In the quick-service industry, I’ve learned the importance of leading with pictures that look delicious,” said Johnson. “People eat with their eyes, not with words.”

“Right now I don’t mind using the plastic menu covers and sanitizing in between.”

It’s not as simple as moving a paper menu into a digital format, though. “How should it be set up, what’s the best way to approach a guest with it?” are questions that operators like Sterling face. “You want to think in that business mindset, where you have your cocktails, your wine, and then you scroll down to the food. It’s really interesting to design a one-page, essentially a working document, that you scroll through.”

Some owners don’t see enough of a pay-off. Nicole Ponseca, owner of Jeepney in Manhattan’s East Village, considered implementing QR codes after she used them when dining at other restaurants, but her guests seem comfortable holding a menu, so she hasn’t yet made the switch. “Right now I don’t mind using the plastic [menu] covers and sanitizing in between,” she said. “And we have the time, since it’s not as busy as before.”

Others say that abandoning physical menus is too big a sacrifice—that the first moments of a restaurant meal, when guests linger over a paper menu, pointing out dishes to friends or designing the perfect meal for one, is an important part of the process, and needs to be preserved. “There’s so much about what was important about Anton’s, before and after Covid, that had to do with the ceremony of dining—ceremony in the sense of a tradition, something that you’re used to celebrating each time you go out and eat,” said Chef Nick Anderer, owner of Anton’s in Manhattan’s West Village. “One of those things, at least for me, growing up, was sitting down and being handed a physical menu that I could look at, and touch, and interact with. It becomes part of the dining conversation.”

The response has been positive. “Most of the feedback that we’ve received about it has been positive,” said Anderer. “Guests have said it’s been refreshing to actually hold a menu,” since so few places still offer them.

Last year we spent about $3,000 printing menus and while that number is tiny compared to our sales, it’s hard to rationalize when the alternative costs nothing, saves time and benefits the environment.

Anton’s invested in a laminating machine so that menus could be sanitized between use, but even with the added expense, Anderer says he’s still saving money. The new menus don’t get stained or destroyed in the way that paper menus did.

To some extent, it’s a guest-driven decision. Emily Egan, a Huertas regular, told me she’s encountered “all the possible [menu format] options” since she and her husband began dining out again in July. And while they find that ordering via a QR code can be clumsy, she’s willing to endure the awkward process. “I prefer not having a paper menu,” she said, “because it’s one less thing to touch. But I still like talking to someone when I order.”

With that in mind, we arrived at a compromise at Huertas. Like Vic’s, we have paper menus for those who want them, but the vast majority of our guests use the QR code. The simple design looks very much like what our guests are used to seeing on paper. And we will still take your order verbally, unlike some restaurants that ask guests to place orders directly from their phones. Last year we spent about $3,000 printing menus and while that number is tiny compared to our sales, it’s hard to rationalize when the alternative costs nothing, saves time, and benefits the environment. But sometimes I reminisce about my first restaurant gig at Chanterelle (which closed in 2009 after a remarkable 30-year-run). The menus there were handwritten works of art, and the dramatically stylized cursive provided an introduction to the meal that at once informed diners that they were in a luxurious environment and signaled the intimate approach to service that came from a family-run operation, with Chef David Waltuck in the kitchen and his wife, Karen, running the dining room (and hand-writing the menus).

I have no prediction about the future, though—about whether we’ll return to paper menus, when we can, or stick with technology and find new ways to celebrate the dining experience. Like everything else right now, it’s up in the air.