BOSTON — Klaas Martens, a prominent voice in the organic movement and a third-generation grain and livestock farmer, says he would be open to using gene-edited crops, as long as they mimic naturally occuring varieties.

That surprise comment, made during a panel discussion at the second edition of CRISPRcon, a gene-editing convention held here this week, is at odds with both federal organic policy and the movement’s cultural orthodoxy. His statements reveal the complexity of defining “genetic modification” as the technology rapidly changes—changes that could bring about an identity crisis of sorts for organic stakeholders.

Martens is a prominent figure in the organic movement. He began farming in New York’s Finger Lakes region in the 1970s, as a conventional grower, before transitioning his farm to organic in the early 1990s. He and his wife Mary-Howell now farm 1,600 acres of organic grain and livestock on the farm, and run a feed and seed business called Lakeview Organic Grain. Notably, Martens is a favorite supplier of Dan Barber, the chef at influential farm-to-table New York City restaurant Blue Hill, who recently founded Row 7, a seed company that uses conventional breeding techniques.

“If it’s used in the same way that current products are, then I wouldn’t have any interest,” he says, comparing gene-edited crops to “Roundup-ready” crops, which are genetically spliced with plant and bacterial DNA to resist herbicides. “If it could be used in a way that enhanced the natural system, and mimicked it, then I would want to use it. But it would definitely have to be case by case.”

Martens’s comments are surprising because organic products, as defined by law under the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB), cannot be certified if they are genetically modified (GMO), or contain individual genetically modified ingredients.

The problem is that new techniques are creating a debate about what “genetic modification” really entails. Until recently, most people used the term to refer to crops created by inserting foreign DNA from one organism into another. This process, known as transgenic mutation, gave us products like Roundup-ready corn, and also Bt corn, which contains genes from a soil bacterium that wards off pests. The injection of foreign genes, which cannot happen on its own in nature, has proved controversial in the past.

Even though CRISPR can be used to create transgenic crops and animals—good old-fashioned GMOs—the emerging consensus is that it’s best to frame gene editing of a plant or animal as an acceleration of traditional methods, and not an unnatural mutation that could not occur outside of a lab. Recombinetics, a Minnesota-based genetics company that used gene-editing tools to develop hornless dairy cattle, as well as swine that never go through puberty, refers to gene editing as “precision breeding,” for example.

Regulators seem to agree. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has decided not to regulate gene-edited crops as GMOs, and has suggested that the crops will not need be labeled with its proposed “bioengineered” label.

“It very clearly is a GMO [method] and has no field history of improved varieties to evaluate what unintended effects the technology might have on the environment, just like all of the GMOs released into the environment have had unintended effects that don’t show up for a number of years,” a board member said at the time.

In 2017, the board further clarified its position on gene editing, and specifically added cisgenesis and intragenesis—that is, genetic manipulation within species, without foreign DNA—to the list of excluded methods, again unanimously.

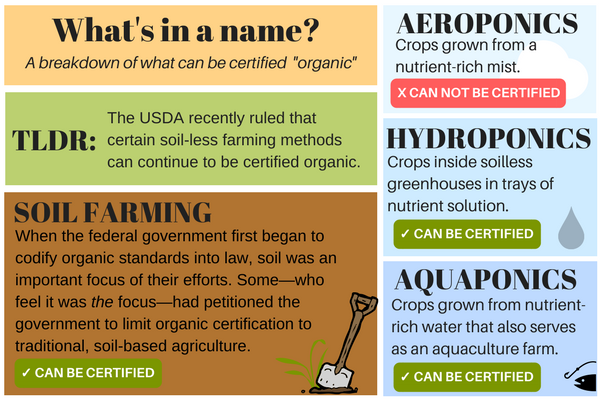

Martens is an organic hardliner. He opposes soil-free hydroponic farming as an organic practice, for instance. “I would listen to someone trying to convince me that it was [organic],” he says, “but they would have to convince me of changing my world view.” He contends that pest-resistant Bt corn is no better than using a pesticide. But he’s open to gene editing, because it could restore naturally occuring crop varieties, that, in turn, could improve soil health—a key concern of organic farming.

While Martens says that he is not speaking on behalf of other farmers, his stature as a long-time leader in the organic community suggests that others in organic, eager to follow in the footsteps of Rudolf Steiner, may soon follow.

“It was intuition that told [Steiner] what was going on,” Martens says. “This is science that finally lets us bridge to that intuition.”