Graphic by Talia Moore / Flickr / Chris Waits

But will this “more is better” sector retool?

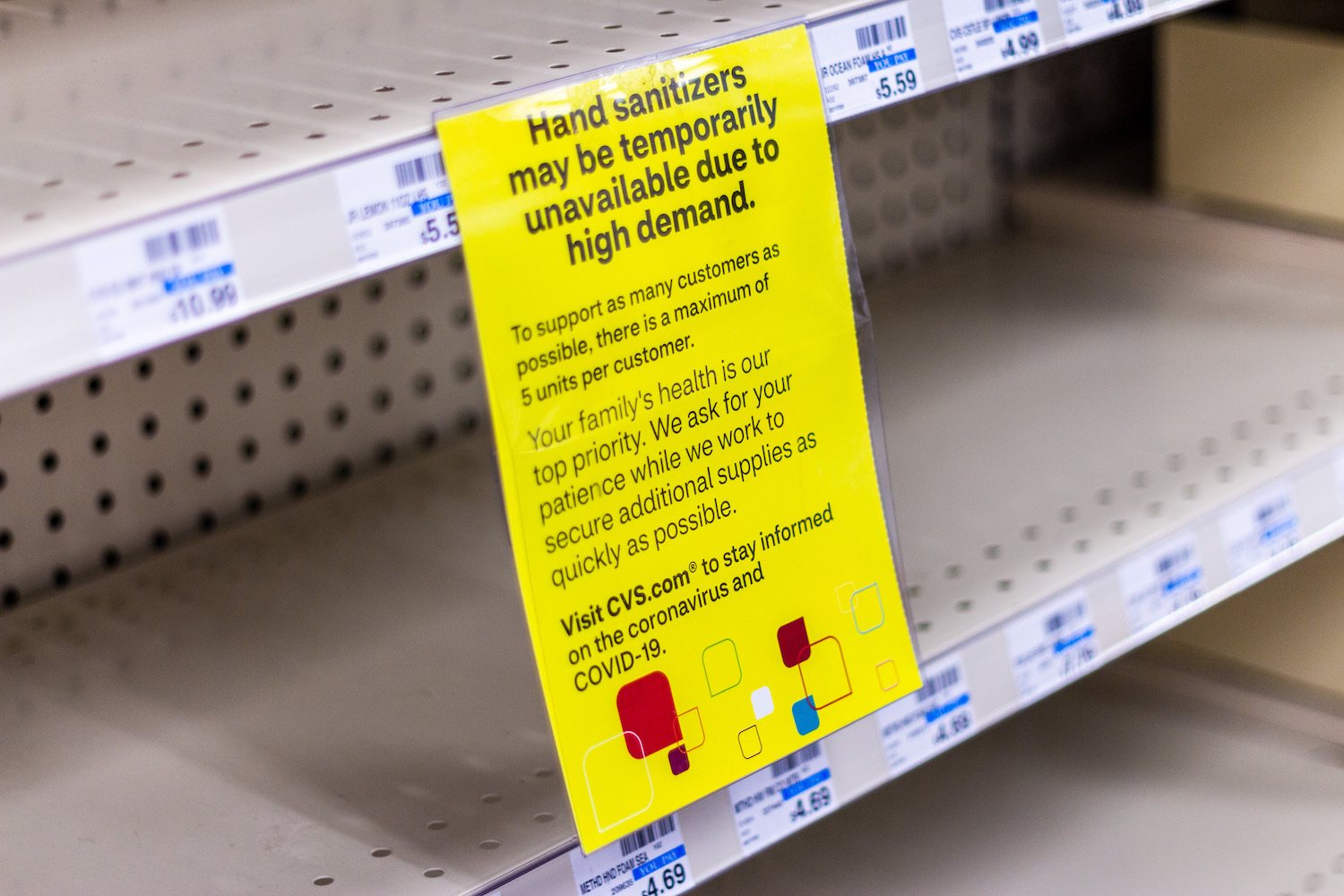

Grocery-store executives and workers remember the empty shelves of last spring. Grappling with another wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, they are bracing for what new variants of the virus may mean for business. They are understandably wary: In the first few weeks of March 2020, panic buying and hoarding led sales of staples to spike by up to 50 percent. Rice, flour, meat, and bleach disappeared.

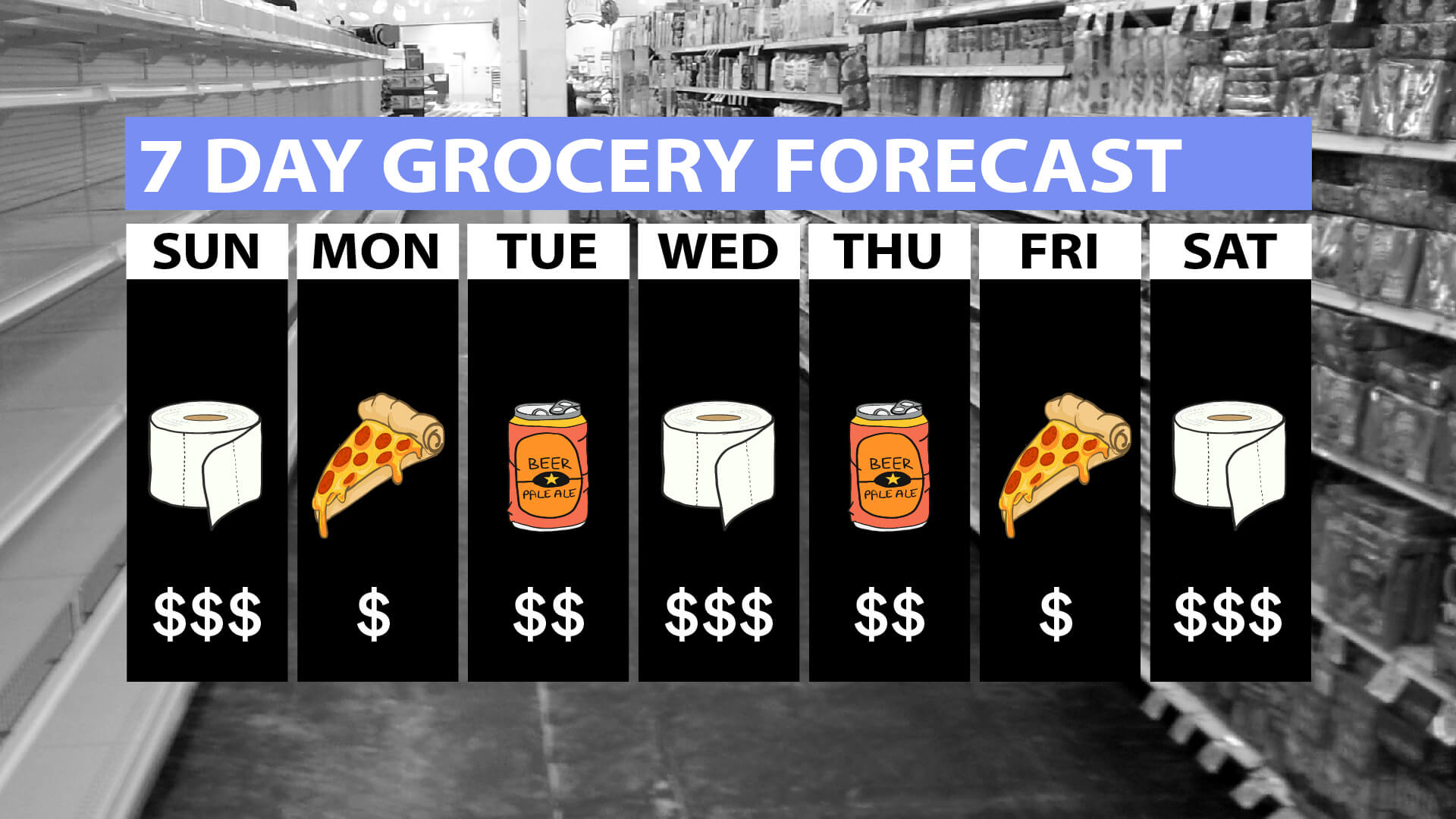

And of course, toilet paper.

Wayne Levy is thinking about why you couldn’t find toilet paper last March. A lifetime analyzing fresh food and packaged good trends is hard to quit: For the past 40 years, the recently retired data scientist has worked in grocery store forecasting, which he describes simply as the science of “what you expect to sell, for a given location, for a given time period.” He’s quick to add, with the tone of someone who delights in the details: “And then it gets quite subtle.”

Levy made a career analyzing what people buy in big grocery chains such as Kroger and Albertsons as well as smaller, regional ones like Giant Eagle. He continues to blend data with empirical observation, through part-time consulting and in his daily life: At the beginning of the pandemic, he began to notice who had toilet paper.

Wayne Levy in his home outside Chicago.

Courtesy of Wayne Levy

“If you went to some of these small stores, they found ways to get toilet paper,” he said. “They reacted immediately because they’re just staring at their one store. In my world [of Evanston, IIlinois], there’s one tiny little store that somehow managed to find some supplier, and they had toilet paper from Day One.”

Grocery stores can’t control consumer panic or disruptions in distribution and supply chains. But forecasters—professionals who track the movement of goods in the past and present to better understand the near and distant future—say last year’s shortages are more than episodic lapses. They’re also opportunities to learn about unprecedented day-to-day changes in shopper habits during this public-health crisis and reimagine how grocery stores can shape-shift to better serve their customers and become more efficient in the process.

The forecaster can be an invisible but valuable force, working behind the scenes across departments from logistics, merchandising, and even information technology. Forecasters may vary in their exact roles, even if they are usually data scientists. But they may follow patterns starting at the store level or all the way up to broader national events and trends. They may be self-employed or work for small data-science companies, or larger companies with an analytics arm like Nielsen Global Media. Due to their many possible roles and settings, the exact size of their field is tough to pinpoint.

“Forecasting accurately at the store-product level provides information that allows retailers to minimize store stocking costs, inventory costs as well as labor.”

But their impact is not. Generally hired by the big chains that can afford them, forecasters can help stores reduce expenses, increase sales, and run more efficiently on every level. It’s worth it to budget in the expense of staffing people (some retailers hire scores or hundreds of forecasters) and computing costs. The insights forecasters provide are important all the time but critical during a pandemic. Drawing on years of experience and lessons learned from Covid-19, Levy and his colleagues have ideas on how grocery stores can work toward a smarter future.

“Forecasting accurately at the store-product level provides information that allows retailers to minimize store stocking costs, inventory costs as well as labor,” Levy said. “Accurate forecasting also allows retailers to detect trends and trend disruptions that can help retailers maintain appropriate stock for products in each and every store.”

Anne-Marie Roerink, president of the market research and data analysis firm 210 Analytics and former research director for the Food Marketing Institute, concurred. She explained how the internal value of forecasters translates to the customer: “There is no bigger detraction from a satisfactory shopping trip than out-of-stock items, particularly when it was a sales item. Happy shoppers tend to shop more often, spend more, and recommend the store to others. Out-of-stock items cost the grocery store a purchase that day at a minimum, but frequent out-of-stocks can drive people to shop elsewhere altogether.”

In other words: If Levy and his fellow forecasters do their jobs right, grocery stores have a better chance of running smoothly and getting shoppers what they want when they want it.

As March 2020 grocery sales rose 29 percent from that month in 2019, many stores struggled with demand, leaving some shelves bare.

Flickr / dmbosstoneThe foundations of forecasting

Here’s how grocery store forecasting works. First, Levy explained, you need to figure out what sort of place you’re forecasting for: a store, distribution center, or manufacturing plant. Take stores, which have overall sales and product-specific goals. On the individual-store level, chains want to maintain the widest variety of available products, get repeat purchases, and increase customer satisfaction. The greater the variety of products they carry, the less room there is on the shelf for each product, and the harder it is to keep everything in stock. And out-of-stock products decrease customer loyalty.

To help a store achieve its goals, a data scientist might start by looking at trends, changes, and patterns. If sales are up, a store might increase shelf space or add more delivery windows. To get the right products, its forecasters might examine patterns in wider geographic areas to find trends that may yet not be visible in its stores. A forecaster would match those patterns to the stores, possibly using that store’s demographics, discounting approach, and more.

From there, the data scientist makes a recommendation. Levy once partnered with a lettuce supplier and grocery store and came to the unsurprising conclusion that people preferred fresher salad greens. Using that finding as a goal, the store worked to improve its processes, moving wilting produce off the floor quicker and streamlining the ordering system. The result: It stocked lettuce that was three days fresher. Demand went up, customers bought more lettuce, and the store reduced waste by up to 40 percent in the process.

The greater the variety of products stores carry, the less room there is on the shelf for each product, and the harder it is to keep everything in stock. And out-of-stock products decrease customer loyalty.

Each solution is customized, exploring everything from consumers’ salad-greens preferences to variations in what people buy for Friday night’s high school homecoming game.

But what happens when you’re hit with a pandemic?

Bracing for new patterns

Some chains handled coronavirus disruptions relatively well. Texas chain H-E-B acted early, communicating with Chinese retailers about the virus in January 2020. By mid-March, it was setting purchase limits on certain high-demand items. Many others did not: As grocery sales rose by 29 percent from the previous year March, stores struggled to keep up with demand, leading to aisles with empty shelves. Eventually, as weeks turned into months and the U.S. government failed to contain the pandemic, supply stabilized: Most items became available again. But people aren’t shopping like they were before.

“Volatility has accelerated so much,” said Jason Lobel. The current vice president of PDI Software, which creates software for the convenience retail market, he’s turned store analytics into actionable numbers for retailers, brands, and distributors for years.

Lobel watched as pandemic buyers flocked to grocery stores and big-box stores for alcohol last March. “Because volumes were up, aluminum cans were in such huge demand that right now there’s an aluminum can shortage. And that’s going to last another year” (and it continues).

The economics of a grocery store depend almost completely on the speed of the inventory or how fast you turn the product.

It wasn’t just alcohol purchase patterns that shifted.

“I know from tracking a lot of these behavioral trends, things like [hot bars] were shut down because nobody wanted to touch food or prepare food. So, instead of retailers selling fresh pizza, hot dogs, hamburgers, in these grocery stores and convenience stores, customers were buying a lot more frozen food. Or packaged food,” he said. Almost a year later, this remains the case.

Picasa

Jason Lobel is the vice president of PDI Software, which creates software for the convenience retail market.

People not only bought different things; they bought what they usually bought in bigger sizes: “Instead of buying a 20-ounce soda at a convenience store, they were buying a 24-pack. And everybody was loading up. So that pantry load caused people to go to stores to buy things they didn’t usually buy at those stores, and then they bought different types of packages.”

Even cigarette sales are up by several percentages for the first time in years, which Lobel also attributes to new behaviors: “People have gone away from e-cigarettes, which were the craze of nicotine users a year ago, back to combustible cigarettes. Even with the greater health risks, people are at home, nobody can see them. They’re smoking cigarettes again. I would have never thought that.”

Speed and size matter

Someday, the pandemic will end. What will grocery stories learn from it?

From my conversations with the forecasters, I got the strong sense that future-facing tactics aren’t a priority for many grocery stores even in the best of times. They also noted that this reluctance was understandable, even predictable; it’s a slow-moving industry with notoriously razor-thin margins. As the pandemic runs its course, chains are caught between scrambling to stay afloat in the face of changing consumer behaviors and periodic shortages at the producer or distribution level.

However, they can use statistical analysis to run the numbers and react.

These methods aren’t new, but according to Levy, you have to forecast fast. Thinking months or even weeks ahead is useless when customers are anxious and feverishly stocking up. He finds short-term forecasting the most useful at any time, but especially when chaos hits, sales surge, and the supply chain struggles.

Toilet paper shortages ruffled shoppers’ sense of security during the early pandemic.

Wayne Levy

“The way I like to do it is to every day look at what happened very, very recently and try to find demand changes. And then quickly update the forecast,” he said. “In my last company, every day I would reforecast 50,000 items for each of 2,600 stores for 31 days forward. Every day, I would redo that forecast.”

With that intense approach, “as soon as there’s a change, your system can say to you, ‘Whoa. Either my forecasts were inaccurate, or something is changing the demand cycle’—and you can very quickly respond.”

The fast forecasting model isn’t cheap or easy. But forecasting for the longer term means companies can miss small differences. By the time they’re clear on the new patterns (according to Levy, often a couple of weeks later), the massive change in demand has already backed up the supply chain. Which means no toilet paper.

“I envision a store with more emphasis on the fresh foods and heat-and-serve in the customer-facing arena—one that offers a smaller, more meaningful assortment of shelf-stable products.”

It’s hard to fix a slow or broken supply chain. And sometimes it can’t be done by numbers alone. Observing and understanding the people behind the statistics, their culture, habits, and emotions makes for better predictions. Knowing a store’s people is easier when that store has less products, fewer customers, and is directly connected to the community.

Levy used his work in Pittsburgh as a serendipitous example of being in touch with a population. He was consulting for an East Coast regional chain when he had a cultural revelation: “The big consulting guy was there, coming to do the study. And he couldn’t figure out why the most profitable product in the store was horseradish. Everyone’s scratching their head, and I was like, ‘Is that the store in Squirrel Hill? Hold on, was this in April?’” Levy is Jewish, and Squirrel Hill is a historically Jewish neighborhood. April means Passover and Passover means horseradish, which in turn means a spike in sales of the bitter herb portion of the Seder plate.

Camilla Sjodin

Bill Bishop, chief architect of Brick Meets Click

Smaller stores are also cheaper to operate. Being smaller could allow a store to operate on what Bill Bishop, chief architect of Brick Meets Click, describes as a resiliency model. Brick Meets Click is a consulting firm that offers research and analytics services to the grocery retail industry.

According to Bishop, grocery stores either build for efficiency or resiliency. He feels most stores have gone too far in building for efficiency, which means no buffer if there’s a huge spike in demand. Sometimes, not having a buffer doesn’t make waves: Low horseradish stock at one Pittsburgh store doesn’t make the news. Being out of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and meat at almost every major chain does.

But even if stores could stock a buffer, not all stores may do it: The economics of a grocery store depend almost completely on the speed of the inventory or how fast you turn the product. If you build for resiliency, Bishop said, “inventory’s going to turn more slowly. You’re going to make less money. There’s lots of resistance to reacting in that way.”

Some of the reluctance to invest in alternative models can be chalked up to fear of profit loss, but it’s never been more critical. Amazon and Walmart are reshaping the industry’s future. And the sector’s been forced to adapt, as the advent of a highly contagious virus sent people to their computers to order food—albeit through clunky proprietary systems or third-party platforms like Instacart.

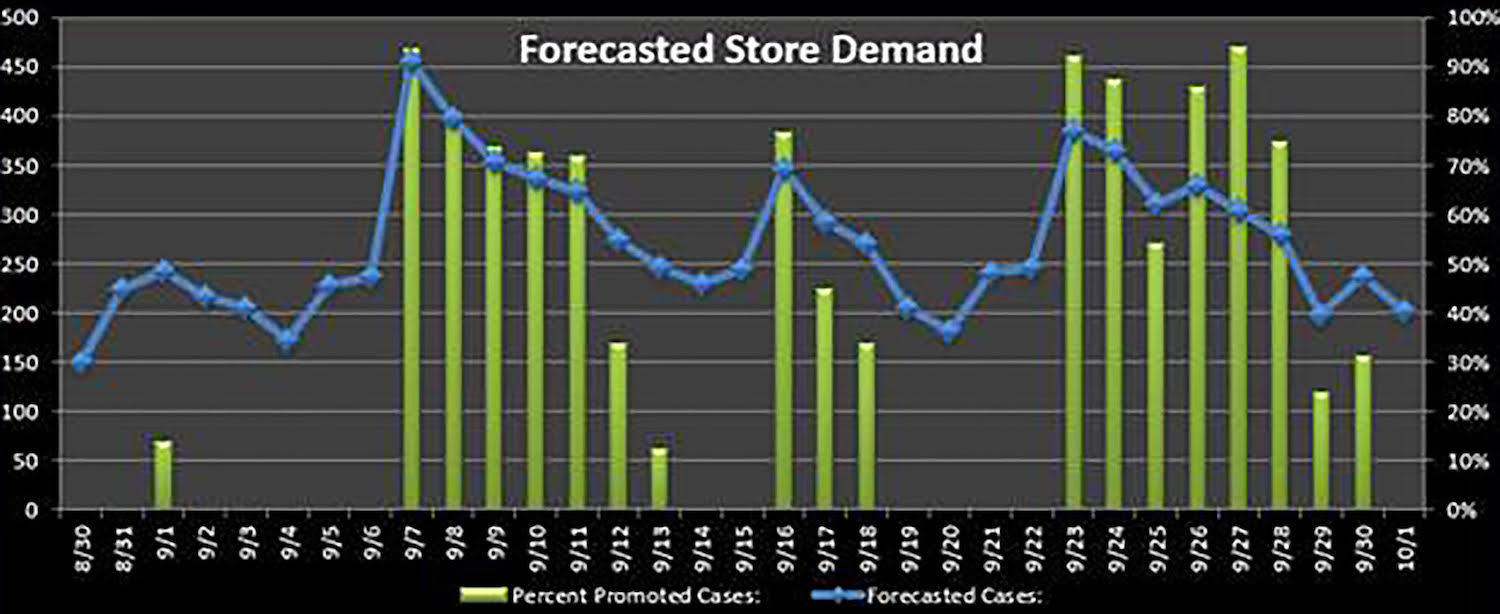

A forecast of promotional sales

Wayne Levy

More online purchases, Levy noted, mean more accurate inventory and better data: “I think it will be one of the good shocks to our industry.”

Numbers from online shopping start to paint a picture—one that could hold the beginnings of a solution. To take one data point from digital shopping carts, known even pre-COVID: People are more comfortable buying nonperishables online versus in-store. This makes a certain sense: You don’t need to squeeze your toilet paper for ripeness, but the best avocados can only be confirmed in person.

But less popular areas suggest room for growth: According to a June 2020 report from global market research firm Mintel, fresh foods like meat and produce may hold the greatest potential; grocery shoppers who do at least half their shopping online are much more likely than less frequent online shoppers to prioritize—and buy—quality fresh products.

Instead of trying to compete with behemoth e-retailers, who can invest billions a year in research and design, Levy suggests that stores could take the opposite tack and go smaller. He believes that stores keep too much inventory on their shelves, which drives up real estate, labor, and inventory costs.

“I don’t think that we can safely make the statement, ‘Big stores are going to go away.’ But I do believe we’re going to see a lot more experimentation, we’re going to see hybrid store formats coming into the market.”

“I envision a store with more emphasis on the fresh foods and heat-and-serve in the customer-facing arena—one that offers a smaller, more meaningful assortment of shelf-stable products,” he said.

In this vision, shelf-stable items could be obtained via pickup or delivery. That would make a physically smaller store and more manageable data sets; stores could forecast more easily, tailor their items to the local population, and distribute products more efficiently. This decoupled model could save time and money. It could also help stores better weather the next disaster.

Former supermarket CEO Gary Hawkins doesn’t disagree, though he envisions a more graduated approach. For 25 years, Hawkins led the New York state chain Green Hills, launching one of the first loyalty programs and earning it the title of “Best Little Grocery Store in America” by Inc. magazine in 2016. Currently the CEO of the Center for Advancing Retail and Technology (CART), he’s an advocate for forecasting, explaining how he’s seen the methods go from “good to great,” moving from forecasting guidance to specific forecasts directly connected to orders and production schedules.

“People that have done their job for the last 10 or 20 years have a challenging time letting go and accepting what the machine is telling them.”

He concurs with Levy’s idea of de-emphasizing shelf-stable items or at least narrowing down the selection to what people really want through data. However, he said, “I don’t think that we can safely make the statement, ‘Big stores are going to go away.’” He believes people love the discovery and experience of big stores too much to drastically reduce their size. “But I do believe we’re going to see a lot more experimentation, we’re going to see hybrid store formats coming into the market.”

According to Hawkins, this could look like a smaller product selection, more of a focus on fresh foods, and shoppers ordering packaged goods ahead of time. He pointed to the Kroger-Ocado partnership, which combines automated fulfillment centers for some shelf-stable items with a more traditional grocery shopping experience, as an example of how the industry is moving in this direction: A customer could order toilet paper and dish soap online, pick it up in the store, and grab a bag of avocados while they’re there.

Switching to a new model would be a big change in an industry that often deals with planned innovation about as well as forced disruption. Hawkins empathized with grocers who have been slower to warm to the benefits of forecasting: The models weren’t always as precise, they knew their markets, and “people that have done their job for the last 10 or 20 years have a challenging time letting go and accepting what the machine is telling them.”

Will stores collectively take a new tack before the next disaster strikes, and will it be successful? The forecasters think they should. Some grocers already are. Only time—and the numbers—will tell what happens next.