Nine years in the making, the rule will make it easier to trace and recall contaminated food. Meanwhile, the Secretary of Health and Human Services now requires his signature on all future rules.

Every time we see a big foodborne illness outbreak—most recently, 1,012 cases of Salmonella linked to red onions—the news sets off a mad dash among the officials at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), farmers, retailers, and distributors to trace the source of the outbreak and remove the contaminated food from the food supply. It’s an imperfect, expensive system, and it can lead to confusing advice: Throw away all onions that came from Kroger or Wegman’s, and also prepared salads that came from Food Lion, and maybe also salsa from Costco. Oftentimes, food safety experts wind up advising that people just throw away all the onions in their pantry and start fresh.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In 2011, the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) was signed into law, requiring FDA to compile a list of high-risk foods and impose new traceability requirements on manufacturers and warehouses. The idea was that, with better recordkeeping, these outbreak investigations could be faster and more targeted.

Fast forward to 2018, and FDA still had not released the rule. “When it comes to a big rule like this, there’s always a political minefield—the general concern about regulations—but then, when you factor in that this is a rule that’s going to identify high-risk foods, there are a lot of industries involved that are worried about being on the list,” said Brian Ronholm, director of food policy at Consumer Reports, and Deputy Undersecretary for Food Safety at USDA during the Obama administration. The new requirements may impose additional costs on some industries, but they may also save money in the long run if they’re able to narrow the scope of outbreak investigations.

“There will be more focus, more attention on these high-risk foods than there would have been otherwise. That will really help consumers kind of be mindful in minimizing their risk of foodborne illness when they make shopping decisions.”

The Center for Food Safety, a public health and environmental advocacy organization, sued the agency to release the rule, and the resulting settlement required that FDA publish the rules by September 2020. The agency complied on Monday, releasing 200 pages of guidance that lay out the new proposed rules for tracing high-risk foods through the supply chain. They will be subject to a public comment period.

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

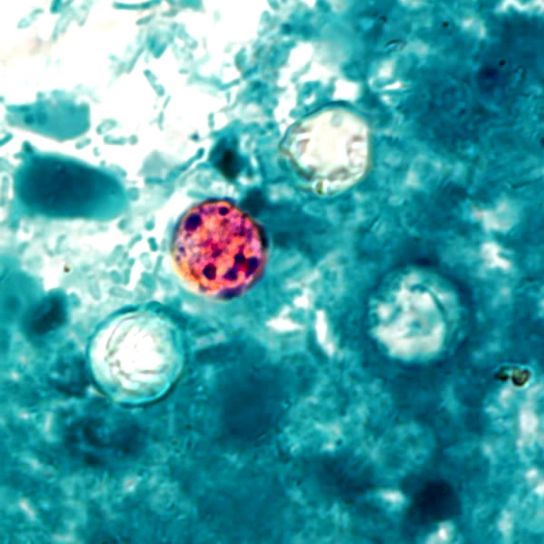

The “high-risk” foods include cheeses, eggs, nut butters, herbs, leafy greens, ready-to-eat salads, shellfish, and others. (Ironically, the traceability rules would not have changed the course of the onion outbreak investigation, because whole onions did not make the “high-risk” list.) The publication of the list may mean as much for consumer awareness as it does for the industries impacted, Ronholm said. “Ultimately, it’s going to help inform consumers on what those high-risk foods are, on a periodic basis. There will be more focus, more attention on these high-risk foods than there would have been otherwise. That will really help consumers kind of be mindful in minimizing their risk of foodborne illness when they make shopping decisions.”

Food Safety News wrote a detailed analysis of the rule, reporting that it covers “some foods, from some sources, some of the time,” adding that FDA “continues to chase a paperless paper trail” by emphasizing digital tracking. Growers of leafy greens—the source of some of the biggest outbreaks in recent years—were quick to point out that they already comply with many of the new guidelines.

“If it’s a situation where the administration is trying to impose political will as opposed to positive public health outcomes, then I think it becomes a serious issue.”

The new rules come as FDA is under increased scrutiny because of the agency’s role in approving future Covid-19 vaccines. Last week, Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar sent a memo to all federal health agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration, that fall under his purview: They were not allowed to sign any new rules regulating food, drugs, or vaccines without his approval, The New York Times reports.

Former Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who ran the agency during the early years under President Trump, called the change “the wrong move at the wrong time” on Sunday’s Face The Nation, adding that regardless of whether or not it’s used to exert political influence on FDA, the memo creates the impression of political meddling. “If it’s a situation where the administration is trying to impose political will as opposed to positive public health outcomes, then I think it becomes a serious issue,” Ronholm said.

During his time with the administration, Gottlieb reportedly fought efforts to implement the sign-off policy. BioSpace, an industry news site, points out that the memo raises fears that the White House could force FDA to approve an Emergency Use Authorization for a Covid-19 vaccine ahead of the November election, but Gottlieb said on Face The Nation that he did not believe such an outcome was likely.

The memo’s implications for food safety rules are less clear. The Trump administration under Gottlieb largely followed the Obama administration’s policies, and Gottlieb voiced interest in defining terms like “healthy” and “natural”—long sore points among consumer advocates—prior to his abrupt departure from the agency. Current commissioner Stephen Hahn was sworn in on December 2019 and has largely focused on the response to Covid-19. In the future, if the new policy stands, it may serve to delay rules like the traceability standard even longer.