Photo by Eric Zamora, The Fresno Bee

Many residents of Central California’s farming communities fear that taking the test will result in losing their job.

This story originally appeared in CalMatters, an independent public interest journalism venture covering California state politics and government.

On Sept. 9, a mobile testing site rolled up to Huron Middle School in the 7,000-person rural city 50 miles south of Fresno. In four hours, only four people showed up for free COVID-19 testing.

At five other coronavirus testing events organized by the Fresno County Health Department that month in Huron and the slightly larger city of Mendota, attendance remained in the single digits.

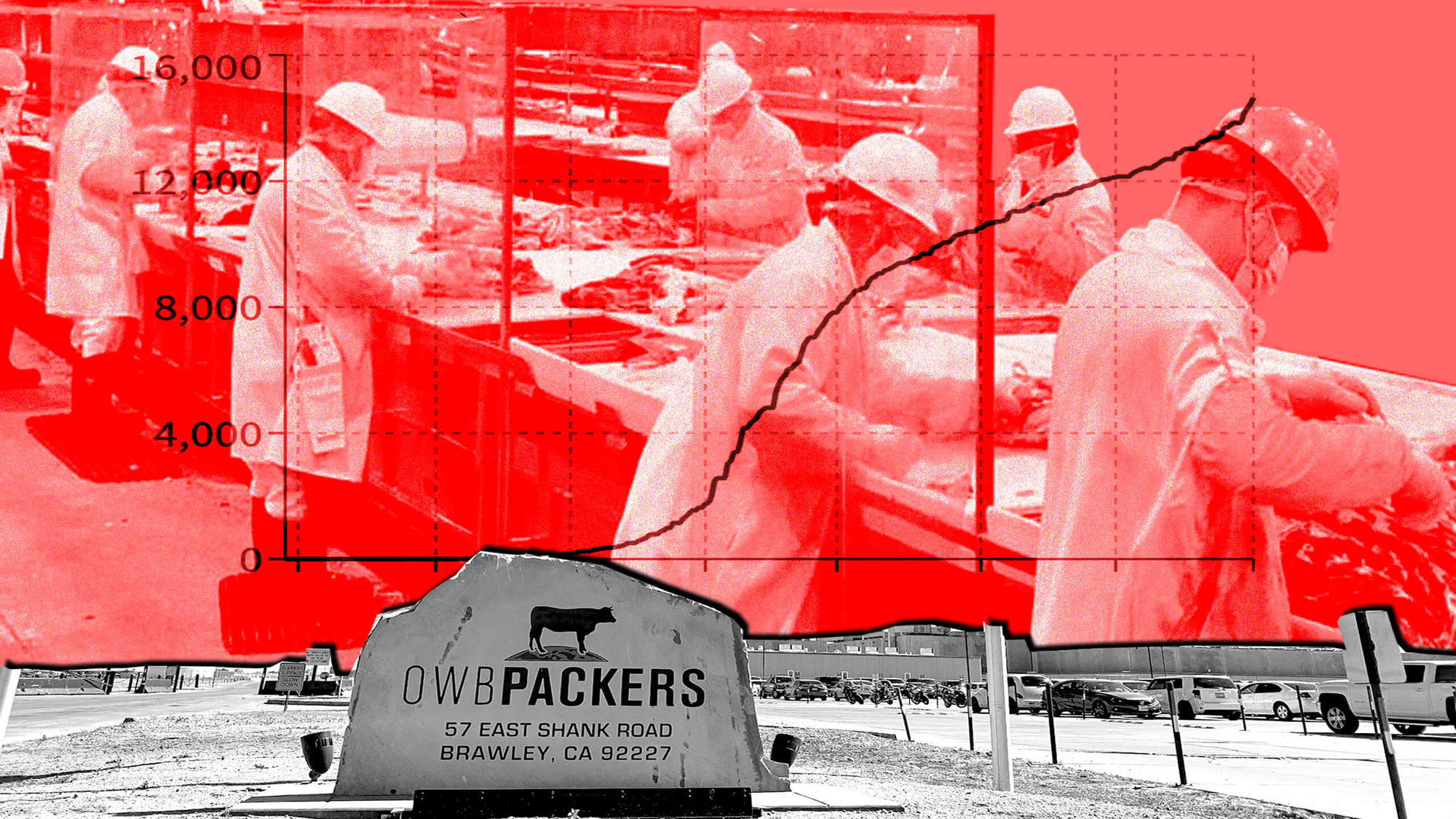

Pictured above, health care workers wait to offer COVID-19 testing at Cristo Rey Church Friday afternoon, Nov. 20, 2020 in Malaga, south of Fresno.

Besides the big cities, the rural farmworker communities of Fresno County have been hardest hit by the pandemic. But eight months into the virus, frontline workers and their families in small towns continue to avoid what experts deem a key step in overcoming the virus — testing.

For some, access to testing remains too remote. Others just never find out that a testing event is happening until it’s too late. Overwhelmingly, however, people in Fresno’s most impoverished communities fear that taking a test will result in nothing but losing their job, missed rent and mounting bills.

To be eligible, Fresno County residents must show financial hardship as a direct result of COVID-19, like close contact or a positive COVID-19 test.

Public health officials say relief is available, regardless of immigration status. But it may be too little too late, and outreach efforts remain out of touch with the community, advocates said.

“I think that there was an immense failure from the county to educate folks on, ‘This is what we know, this is what needs to happen, and these are the resources we have put out for you all,’” said Leslie Martinez, a policy advocate with Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability.

“Through an advocate lens, it’s been really frustrating and heartbreaking to work with community residents.”

‘If I do have it, what am I going to do?’

Fifteen years ago, Rosario Rodriguez moved from Mexico to Three Rocks, a small unincorporated community 50 miles west of Fresno surrounded by almond and pistachio fields.

She, her husband, and their two daughters never got tested for the coronavirus. Fear, misinformation and a lack of financial relief are reasons.

“What if they tell me I have it, but I don’t? What if they put the virus in me? And if I do have it, what am I going to do? That’s the fear of everyone here,” she told The Bee in Spanish. “People don’t have insurance, and they can’t get access to unemployment. So what resources are left for us?”

“If you’re positive, you stay home. You lose your job. You lose your pay. You get quarantined from your family. I mean, we’ve got a real barrier to overcome with that.”

Fresno County public health officials say they know what they’re up against.

“There’s no benefit if you’re a farmworker if you get tested,” said Wayne Fox, director of the county’s Division of Environmental Health.

“If you’re positive, you stay home. You lose your job. You lose your pay. You get quarantined from your family. I mean, we’ve got a real barrier to overcome with that,” he said.

False claims that the government is giving people the virus have also made the county’s job more difficult, Fox said.

Cash assistance available in Fresno County

The state of California has mandated two weeks of paid leave for all employees. But employers have little incentive to remind them of what’s available, Fox said, and workers with precarious immigration status are often scared to demand it, advocates explained.

In partnership with the state, Fresno Economic Opportunities Commission launched Healthy Harvest in the summer, a program for farmworkers to get a free hotel room, meals, and transportation if they test positive or as they await a test.

So far, only five people have used their services, according to Kristine Morgan, communications manager for EOC, “but the word is just starting to get out there.”

“If you’re a farmworker, you’re not accessing the media; you’re not going to websites, you probably don’t have internet.”

Armando Valdez, director of Community Center for the Arts and Technology in Fresno, said the program was failing because it doesn’t take culture into consideration.

“Listen, Latinos are very united. We raise our families, and we don’t want to let go,” he said. “What I suggested is keep those families in their homes but give them the financial support so they can stay there. That was the suggestion a lot of our families were giving us. We will be quarantining, but keep them here. Help us financially.”

That help finally has arrived.

The COVID-19 Equity Project, launched late this summer as a result of $10 million set aside from federal CARES Act grants, has made available $1,200 in cash assistance for Fresno County residents who are sick or were exposed to the virus.

But few community members know about it.

“If you’re a farmworker, you’re not accessing the media; you’re not going to websites, you probably don’t have internet. So, this is something we’ve got to do a better job of making sure we get the word out,” Fox said.

To distribute the aid, the county paired up with 22 community-based organizations to serve immigrants, refugees, Black residents and people with disabilities. The idea is to reach people through “community health workers” who already form part of their community.

Residents can get in touch with the participating organizations to apply for aid.

To be eligible, Fresno County residents must show financial hardship as a direct result of COVID-19, like close contact or a positive COVID-19 test. The groups use different criteria to assess each household. Assistance is then given out through cash and by paying bills, like rent or utilities, according to Tania Pacheco-Werner, a research scientist at Fresno State who leads contact tracing and training efforts on the Equity Project.

County struggles with testing outreach

For the first half of this year, Rodriguez lived in the slightly more central town of Cantua Creek, around the block from Cantua Elementary School. She visited the school daily to get breakfast for her two daughters. But she never found out about a testing event there on May 13 until a friend asked if she had been tested.

“I never saw a single flyer. There wasn’t much outreach so that people would know. I don’t think very many people showed up. I was there every day!” Rodriguez said in Spanish. “If I didn’t know then, how would people who live in Three Rocks or Halfway find out?”

According to the county health department, a total of 16 people were tested that day in May, more than the average of 12 people who showed up to their other rural testing events that month. Dave Pomaville, director of the health department, said the weekday, midday events were likely unpopular because of timing and because they lacked local clinic partners at the time.

“They’re still not where we’d like them to be, but we went from single-digit numbers into double-digit numbers.”

Since the Equity Project launched in August, the county has partnered nonprofits with federally qualified health clinics to provide somewhat regular testing events. Partnering with these organizations has been crucial in building community trust, according to Dr. Trinidad Solis, who coordinates the Equity Project for the county.

At first, testing was only available during the workday. Attendance went up as they expanded into later hours and weekends.

“They’re still not where we’d like them to be, but we went from single-digit numbers into double-digit numbers,” said Fox, who also coordinates the project.

Why did outreach take so long?

Community advocates and local growers have been insisting on ideas like regular, local testing, and cash relief for months.

In June, west Fresno rancher Don Cameron told the county testing times in the middle of the workday were inconvenient for workers, he said in an interview. He suggested workplace testing.

Fox said they are only now starting to plan regular, returning testing sites, and workplaces are beginning to organize their own testing events.

Isabel Solorio, who organizes a food bank in the small farmworker town of Lanare, said she started asking for testing for her community in April.

“After six months, we got one. This is shameful. You hear about testing all over Fresno, except in the rural areas,” she said in Spanish.

Pomaville said coordinating testing has been an immense effort. Rural health clinics are already few and far between, and early versions of the COVID-19 test required a traditional lab environment.

“You hear about testing all over Fresno, except in the rural areas.”

He said he believes the answer lies in employers allowing employees to go to a clinic to get tested during work hours and expanding testing options that are less invasive and can be done out in the field.

“It’s been a lot of scrambling, and as soon as we think we have a plan in place, then things are changing,” Pomaville said. “But I think there have been huge steps in testing.”

Community advocates like Valdez say they believe elected officials don’t do enough to protect these communities because the undocumented aren’t part of the electorate.

Pomaville said he understands why many of these communities feel disenfranchised.

“We need to be more inclusive. I’m going to tell you, today we are not as inclusive as we want to be or need to be,” he said. “Sometimes advocates that are advocating for this feel like they’re not being heard. Sometimes it takes a little bit of time for that message not only to sink in but for the action to follow.”

Larger issue?

The county’s slow response is a symptom of a much bigger issue, according to Pacheco-Werner, from Fresno State.

“You’re trying to catch up a public health infrastructure with decades of ongoing disinvestment overnight. People may think the starting point was here. No. The starting point was at negative.”

Small, rural communities like Cantua, Lanare, Huron and others developed as workforce farm labor towns. They were never seen as communities, but labor centers, she explained. Besides poor access to health care, most residents have lacked access to basic infrastructure and clean drinking water for decades.

The virus is simply opening up more people’s eyes to rural realities because “we’re all drowning in these numbers,” Pacheco-Werner said. “With COVID, you can visibly see what happens when you don’t try to make communities whole.”

Once a vaccine rolls around, the county will have to overcome the same barriers it has faced with testing, Pomaville said, “but hopefully we as a community are better prepared, as well.

“Hopefully, when the pandemic’s over, we are able to keep this framework together to solve the other problems we had before COVID started.”

Manuela Tobias is a reporter with The Fresno Bee. This article is part of The California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequity and economic survival in California.