AP Photo/Mark Lennihan

This designation gets them state-funded child care, but labor advocates want more: free coronavirus tests and access to protective gear.

In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, grocery workers have become unlikely heroes on the order of doctors and nurses. How’s that? Because as most of America has been ordered to stay home and shelter in place, it’s the clerks, cashiers, stockers, and delivery drivers who still have to work, risking possible infection to keep people fed.

And how are they being thanked? In some states, governors have issued executive orders to officially designate those grocery workers as essential or critical personnel, which makes them eligible for free child care. Minnesota and Vermont were first to act, and in the weeks since, Michigan and Maryland have followed with similar orders.

But feeling like a hero isn’t the same as hero status. The country’s largest grocery union, the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), has petitioned governors across the country to officially classify their 1.3 million members in supermarkets, pharmacies and processing plants not merely as essential, but as first responders—a status conferred to firefighters, police, and paramedics.

In some states, governors have issued executive orders to officially designate those grocery workers as “emergency personnel,” which makes them eligible for free child care.

Doing so, union leaders say, would qualify grocery workers for government support and protection that’s desperately needed in these unusual times—not just child care, but also free coverage for coronavirus tests and treatments, and priority access to personal protective equipment to stay safe on the job.

“More must be done,” said Mark Federici, president of a Washington, D.C.-area UFCW local, which represents around 35,000 workers, in a statement on Friday responding to Maryland’s “essential” classification.

The union’s petition is part of a full-court press, launched by organized labor, progressive politicians, and grassroots movements, in government and the private sector, to ramp up protections for workers during the pandemic. (This week alone, Amazon, Instacart, and Whole Foods workers have all walked off the job, demanding higher pay, safer working conditions, and sick leave policies that they say would help stop the spread of the virus.)

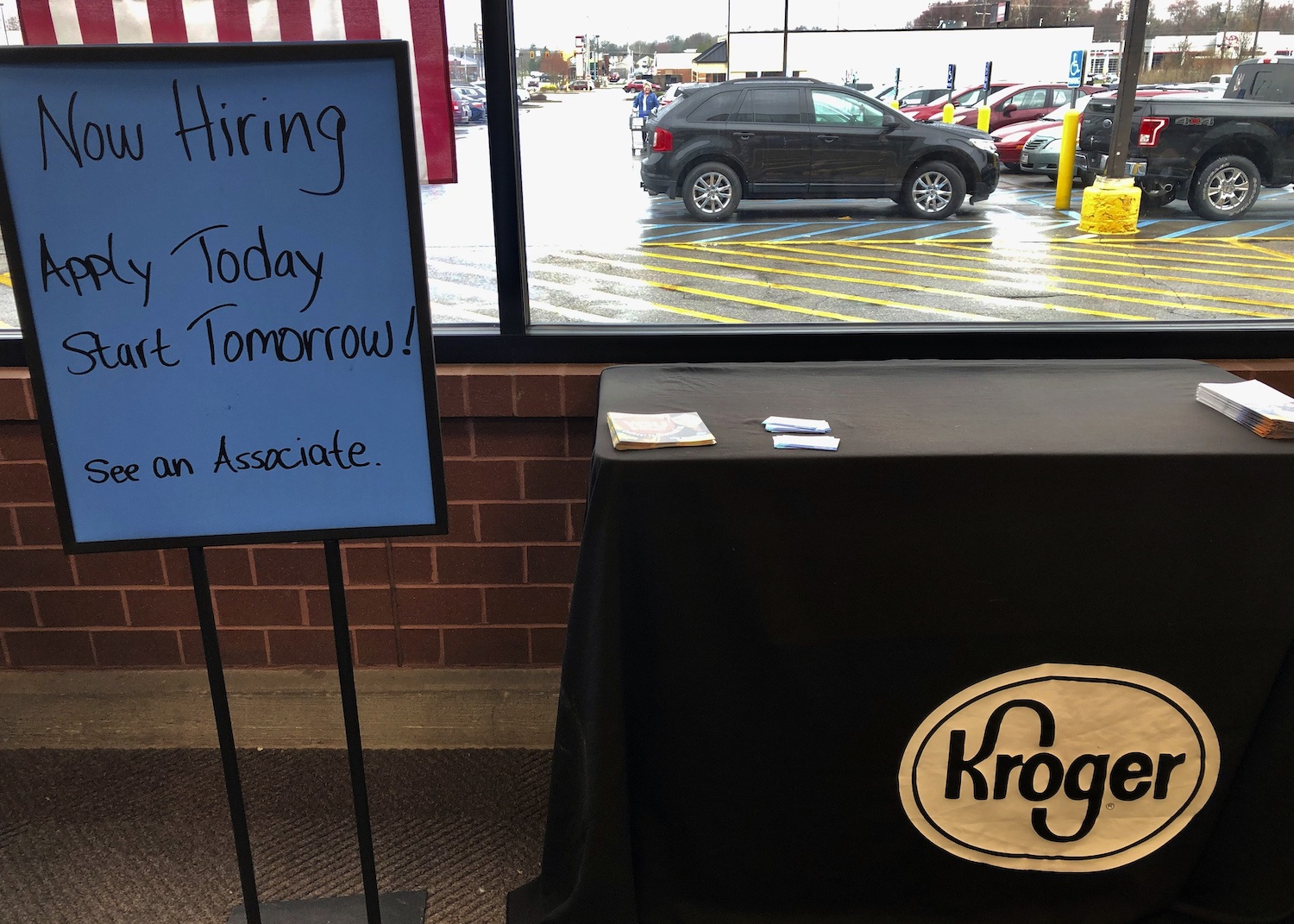

Some of the union’s demands, like a two-week paid sick leave and extended unemployment benefits, made their way into the recently passed Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Additionally, its largest employers, like Safeway, Kroger, and Walmart, have given out temporary raises, doled out bonuses, and installed protective equipment like sneezeguards.

Some of the union’s demands, like a two-week paid sick leave and extended unemployment benefits, made their way into the recently passed Families First Coronavirus Response Act.

In the U.S., free or reduced-cost child care programs are handled state by state, backed primarily by a billion-dollar federal block grant. These programs are sorely underused, with only around 15 percent of more than 13 million eligible children participating, according to a recent government report.

Karen Schulman, a research director at the National Women’s Law Center, says that’s partially because federal subsidies don’t cover enough of the actual costs. That could change with last week’s passage of the CARES Act, a massive coronavirus stimulus bill that includes a $3.5 billion boost for child care programs for essential workers.

Getting grocery workers reclassified as essential workers is the first step towards making sure they qualify, but she worries it may not be enough.

“They’re under tremendous pressure right now, working long shifts,” she said. “When are they finding time to learn about this assistance for child care and apply for it?”

“That first week that my daughter was out of school, it was kind of a struggle,” she said. “My child care is school. And since school’s out, I do not have child care.”

That classification could benefit Amber Stevens, a cashier at a Shoppers grocery store in Forestville, Maryland. Stevens needs someone to watch her 9-year-old daughter, now home every day after her elementary school shut down. Initially, Stevens said, she had to miss work to take care of her, and as an hourly employee, that means lost wages.

“That first week that my daughter was out of school, it was kind of a struggle,” she said. “My child care is school. And since school’s out, I do not have child care.”

This week, she said, her mother, a government employee, has been working from home and watching her daugher. Stevens, however, checks out around 200 customers every day, and she’s running low on cleaning supplies at her register. Those working conditions make her, and other supermarket workers in her position, far more likely to catch the virus, and then pass them onto their family members, some who have become de-facto child care providers.

That’s forced some grocery workers to make difficult decisions. Sean Krane, a meat cutter at a Vons supermarket in San Pedro, California, said crowds have surged, and a special occupancy limit of 100 people isn’t being enforced. He said he hasn’t seen his girlfriend or their five-year-old son for a week, because he fears he’s likely to catch the virus, and doesn’t want to transmit to her parents.

Those working conditions make her, and other supermarket workers in her position, far more likely to catch the virus, and then pass them onto their family members, some who have become de-facto child care providers.

“It’s hard,” he said. “Some people only have their parents, and they don’t want to come home and pick up their kid, and then their kid goes give it to their parents, while they’re watching them at work.”

California Governor Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, has not responded to Krane’s union’s petition to get him paid child care. The union’s petition to reclassify grocery workers as emergency frontline personnel includes a number of other requests, like the right to free Covid-19 testing, additional sick days, and the enforcement of crowd control. (A state spokesman referred The Counter to a public website for information.)

Governors in Texas, West Virginia, and Virginia have not responded to similar petitions, according to union officials, nor have they responded to The Counter’s requests for comment. The governor of Missouri said he opposes the request.

“There are just more and more reports and cases of grocery workers who are falling ill, who are so deeply anxious about health concerns at work, for themselves and their families, or even spreading it to customers.”

Emergency classification is a tough ask in those states, simply because the unions aren’t as politically powerful or connected there, says John Logan, a labor historian at San Francisco State University who has called for more government protections for grocery workers. If the domino falls, lawmakers there may feel compelled to classify workers in other industries.

But in the weeks ahead, as more grocery workers test positive, or even die from the virus, as has happened in Italy, he expects to see more rights granted to supermarket workers. The tremendous danger they face, simply by going to work, will become more apparent. Potentially, that could include not just child care, but also the emergency benefits that unions have already demanded—particularly if California leads.

“There are just more and more reports and cases of grocery workers who are falling ill, who are so deeply anxious about health concerns at work, for themselves and their families, or even spreading it to customers,” he said. “They are at considerable risk because of the number of people they deal with on a daily basis, and there’s so much you can do to make the job much safer.”