Northshore School District / Alex Clark

Facing the possibility of more shutdowns, school officials are trying to develop contingency plans to keep kids fed—particularly those who rely on free or reduced price lunches. Some say the federal government could be doing more to help.

On Monday, more than 25,000 students in the Northshore Public School District, located in the greater Seattle area, began to attend class virtually. Officials canceled in-person instruction last week due to concerns about the coronavirus, which has spread rapidly in Washington State.

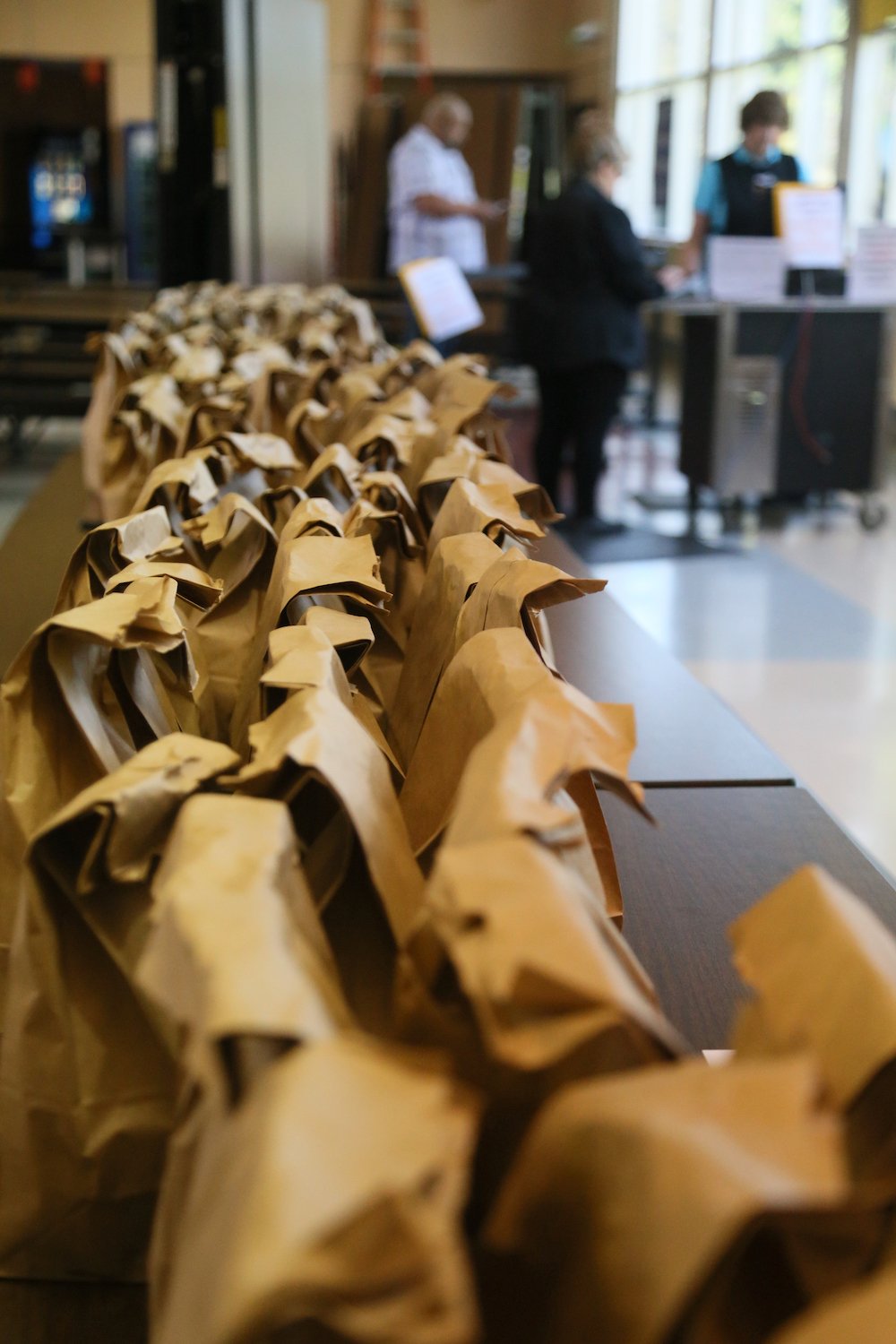

Above, a school nutrition official in Washington State’s Northshore School District packages a grab-and-go meal of orange chicken, carrots, and rice.

Monday marked the launch of a new program that allows students to order lunches online and pick them up in school parking lots across the district during the upcoming stretch of remote learning.

The move is intended to keep educators, students, and their families safe, but presents serious logistical challenges. Loaner computers were provided to those without one. Hotspot devices have been made available for those without internet. But technology is only one part of the challenge of teaching kids remotely. What about the students who rely on school for access to nutritious meals, or might otherwise go hungry when class is not in session?

According to state data, more than 2,600 Northshore students are eligible for free or reduced-price meals, an indication of household food insecurity—nearly 12 percent of all students.

“Many of our families depend on school meals,” said Juliana Fisher, director of food services for the school district. “It’s extremely important that we’re there to provide that for them. Asking [students] to perform in an academic way without also supporting them with basic needs is unreasonable.”

As part of a unique lunch program tailored to the challenges of learning remotely, Northshore now offers a stopgap nutrition program that allows students to order food online and pick it up at 22 locations across the district. From 6 p.m. the night before a given school day through 9 a.m. the morning of, students can order one of two lunch options—one vegetarian, the other not—through a web form.

“For many families, school is the only place to get meals for the day and that need continues even if a school closes.”

From there, staffers prepare and package those meals at one of five operating school cafeterias. Bus drivers, not responsible for dropping off and picking up kids for the time being, have become de facto delivery drivers, tasked with bringing food from kitchens to pick-up sites around the area (usually the parking lots of temporarily-shuttered schools). Students can either grab their meals at a pick-up site within a designated 15-minute window, or buy one à la carte at an operating in-school cafeteria between 11 a.m. and noon. Parents accompanying their children to the cafeteria can also buy a lunch for themselves, for $4.30 cash, while students charge their food to their school accounts.

Northshore School District / Alex Clark

Grab-and-go lunches ready to be distributed to pick-up sites throughout the Northshore School District

“Today was the first day, so we are working out kinks,” Fisher told me, on Monday afternoon. Still in the works are efforts to conduct outreach to families whose primary language isn’t English, to find ways to deliver meals to students who can’t access pick-up sites, and to ensure that classes don’t overlap with food delivery windows.

Northshore straddles two counties that have been heavily impacted by COVID-19, the severe respiratory illness caused by this year’s novel coronavirus, SARS-COVD-2. To the south is King County, which has seen 116 confirmed cases and 20 deaths, per recent numbers from the state health department; to the north lies Snohomish, with 37 cases and 1 death. Prior to the district’s transition to online classes, 26 of its 32 schools had been affected by direct or indirect exposure to the virus. One in every five students had called in absent. Taking instruction online wasn’t just a matter of protecting the health of kids, but that of staffers, too, wrote superintendent Michelle Reid in a letter last Wednesday announcing the move.

But if Washington State is currently an outlier in the U.S., the specter of a viral pandemic has raised concerns about schooling disruptions elsewhere. According to an analysis of local reporting and school websites by Education Week, 381 schools serving more than 250,000 students have closed due to COVID-19 exposures as of Monday. The outbreaks’ scale poses an unprecedented nutritional challenge, and schools may be forced to fulfill their duty as meal providers in creative, unorthodox ways.

“Emergency feeding tends to be provided through more of a patchwork or piecemeal avenue because typically the disasters are so localized,” said Diane Pratt-Heavener, communications director for the School Nutrition Association, which represents child nutrition professionals. “There’s not really a vehicle for widespread school closures for a lengthy amount of time, for schools to be able to consistently provide support in this way.”

Northshore students can order one of two lunch options—one vegetarian, the other not—through a web form, which staffers then prepare and package at one of five operating school cafeterias. Bus drivers distribute those meals to pick-up sites around the district.

Northshore School District / Alex Clark

In New York City, home to the largest public school system in the country, Mayor Bill de Blasio has called closures a “last resort,” citing the role that cafeterias play in children’s nutrition.

“We know that for many families, school is the only place to get meals for the day and that need continues even if a school closes,” said Miranda Barbot, press secretary for the New York City Department of Education, in an emailed statement. “If a school is closed for 24 hours, we’re prepared to serve grab-and-go breakfast and lunch for any student who wants it.”

Many other schools are making similar contingency plans. But some, particularly those in rural areas, face particular logistical obstacles. For example, in the Colville School District in northeast Washington, some students live up to an hour-long bus ride away from school. Last week, when classes were cancelled Monday through Wednesday due to a potential COVID-19 exposure, the school was unable to distribute lunches to students, says Colville School District superintendent Pete Lewis. Up to 40 percent of students in some Colville schools qualify for free and reduced price lunches, per data from the anti-hunger advocacy group Food and Research Action Center.

Some officials have suggested that the Department of Agriculture (USDA), which oversees the national school lunch program, could do more to support children’s nutrition when closures or remote learning become necessary. On Friday, the agency announced that it would waive a key restriction on emergency food programs: the requirement that schools serving free meals during unexpected closures do so in a group setting. By lifting this mandate, USDA allows schools to serve “grab-and-go” meals to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19.

“Areas that are not designated as high need, still have students in need.”

Still, this change may prove to have limited impact: The only schools permitted to serve free meals during a closure in the first place are those in areas where 50 percent or more students qualify for free and reduced price lunch. This means that schools that don’t meet the high threshold—but that nonetheless play an important role in feeding kids breakfast and lunch—won’t be able to do so in the event of a shutdown.

“Areas that are not designated as high need, still have students in need,” said Leanne Eko, director of child nutrition services for the Washington public education agency, in an email. The state has filed a waiver request with USDA to allow all schools to serve food in the case of a closure related to COVID-19. At the time of writing, USDA has not approved it. (In a request for comment, USDA sent The Counter a link to its announcement that it had waived the group feeding requirement.)

Most Northshore schools, for example, don’t meet USDA’s 50 percent threshold, even though there are areas throughout where a high proportion of students qualify—including an elementary school with a free and reduced price lunch participation rate of 37 percent. Allowing all schools to provide universal lunch to students during the COVID-19 emergency would make nutrition more accessible in a time of need, Fisher says, by cutting out onerous meal-counting requirements, and allowing students from outside the district to get food, as well.

There are still a few finishing touches to put on Northshore’s program, which Fisher believes will be resolved in due time. Instruction will remain off-campus for at least another week, possibly more—but don’t call it a closure.

“We’re not closed,” Fisher says. “We have transitioned to a different model. And so we’re still needing to provide services through our normal avenues, just in a different way.”