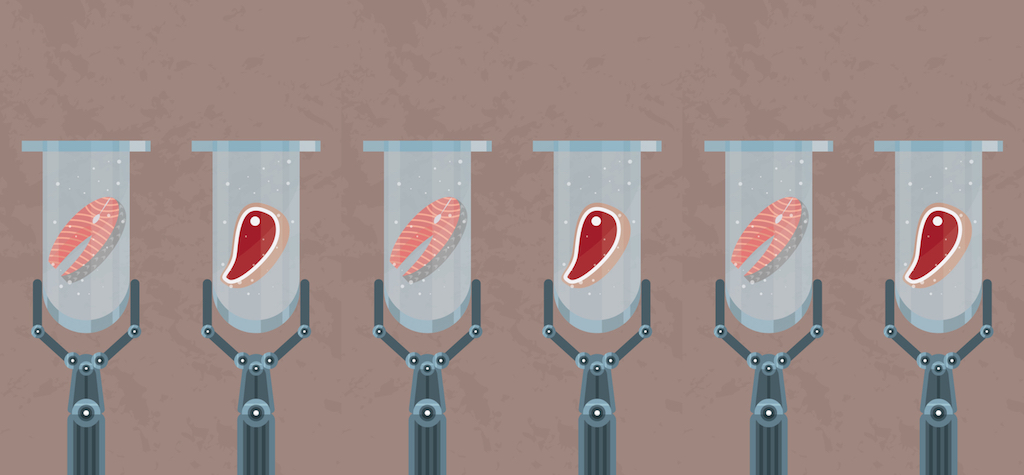

iStock / Valentina Kruchinina

Right now, a group of companies are racing to introduce you to a radically new kind of food: “meat” cultured in labs, rather than grown on farms. Maybe you’ve heard about these products, which don’t require animals to be raised or slaughtered. Sometimes they’re called “clean” meat. Or “lab-grown” meat. Or “synthetic.” Or “in-vitro.” Or “cell-cultured.”

Biologically, these products are meat. But it could take a wholesale reimagining and redefining of a food group that many people feel very passionate about before they accept it on their plates. And that work that is already playing out in battles over what, exactly, to call this stuff. Proponents of cellular agriculture are faced with a marketing dilemma: What do you call a product to stress that it’s a major departure from the familiar, without conjuring images of a sinister science experiment (“vat meat,” anyone?) that will surely stress people out?

Photo by Just / Collage by NFE

Photo by Just / Collage by NFE What do you call a product to stress that it’s a major departure from the familiar, without conjuring images of a sinister science experiment that will surely stress people out?

So far, the industry’s solution has been to use the term “clean” meat—emphasizing lab-grown’s environmental footprint, which supporters say is only a sliver of traditional meat production’s. But how many people really want to think about offsetting carbon while they enjoy a burger? Which is why Jack Bobo, a biotech industry veteran, has an alternative suggestion: Ditch the “clean” and call it “craft meat.” The idea is to position cellular ag as a kind of idealistic upstart, one focused on taste, exclusivity, and bespoke production—to the meat industry what craft beer is to AB InBev.

I saw Bobo speak at AgTech Nexus, an investor conference held in Boston earlier this month.

Until 2015, he was a senior advisor at the Department of State on global food policy. These days, he works for Intrexon, a diabolical-sounding biotechnology company that owns some of the biggest names in biofood—the genetically-modified (GM) food companies AquaBounty and Arctic Apples, and the cloning company ViaGen—along with OxiTec, the company behind zika-fighting GM mosquitoes. Bobo expects most meat eaters will feel antagonized by companies that say their products are “clean.”

Historically, food companies have appealed to potential companies by marketing the taste, price, and convenience of their products. More recently, an appetite has emerged for products marked with “credence qualities”—attributes that suggest a food was produced in a way that’s better for you, or for the earth. And the buzziest, most anticipated lab-grown meat companies, like Just Foods, Memphis Meats, and Finless Fish, have latched onto that approach—pitching consumers by stressing the morality of their products above all else. But if these companies want to be as big as Cargill—one of the world’s biggest livestock companies, and an investor in Memphis Meats—they have to market themselves in a way that speaks to everybody, not just those who eat their values. Enter “craft”: A word that is perceived by many to stand for quality, for skill, independence, uniqueness, and in the world of beer, innovation.

“You want your product to be exciting and new, and that’s what’s gonna get people to adopt it,” Bobo said. “They’re not gonna try it just because, you know, we’re trying to save the planet, they’re gonna try it because, ‘Hey, that’s $20 a pound, I wanna try that meat.’ You want it to be a quality, exciting exclusive.”

In the world of craft brewing—and craft chocolate, and artisanal food in general—small-batch production is part of the ethos. In some cases, that’s by virtue of necessity: Plenty of craft brewers, for example, don’t produce enough beer to afford retail distribution. With cultured meat, the limited availability is actually one of its biggest criticisms. These companies have big valuations, and are being bankrolled by some of the world’s wealthiest investors and most prominent venture capital firms, after all, but still have struggled to bring a product to market after taking on hundreds of millions of dollars. What Bobo is talking about is turning a liability into an asset, spinning lab-grown meat’s limitations as exclusivity appeal.

Photo by Memphis Meats / Collage by NFE

Photo by Memphis Meats / Collage by NFE Rather than suggesting that their lab food is Southern fried chicken, maybe San Francisco-based Memphis Meats should actually open up a clean meat lab in Memphis

Part of what makes lab-grown meat unique is that it’s going to be made in only a few places, at least at first. And unlike traditional livestock, which are raised on farms way outside of town, lab-grown companies may be able to operate closer to cities—where consumers are. This approach could even allow the lab-grown companies to lean in to the local angle: A craft meat for every market with a local identity. Rather than suggesting that their lab food is Southern fried chicken, maybe San Francisco-based Memphis Meats should actually open up a clean meat lab in Memphis.

“Production is likely to be small at first anyway, so take advantage of the things that they’re doing, which is they’re brewing meat, they’re creating it in fermentation, that it’s going to be a local production,” Bobo says, in a phone conversation with the New Food Economy. “They’re located inside these city limits, unlike a CAFO, which is as far away from the city as people make them go.”

Which isn’t too dissimilar, as it turns out, from the very place craft beer is in, today—considering that the world’s largest beer companies are snapping up celebrated breweries, and launching “craft” labels of their own. That’s exactly what we’re seeing in the nascent lab-grown meat industry. So maybe these products, in the end, won’t be quite as disruptive as they seem to be. Maybe the best lab-grown burgers and foie gras will turn out to be, when it’s all said and done, the rarer, tastier, Goose Island IPA, to Big Meat’s Bud Light.