How to describe Prime Day?

It’s Amazon’s annual offering to its paid Prime users, the impatient souls who pay $99 a year for free 2-day shipping and special discounts. It’s part Cyber Monday, part ad campaign, part pledge drive—a highly publicized bargain-fest you have to pony up to take part in. And it’s a 30-hour binge for Amazon’s Prime members, who’ll try to cram in all the savings they can before midnight tonight.

This year’s Prime Day comes hot on the heels of Amazon’s bid for Whole Foods, and as such it was supposed to be an occasion for the online retailer to flex some grocery muscle. It’s an opportunity, writes Food Dive’s Christopher Doering, to take advantage of “the immense popularity of the annual discount extravaganza … the buzz surrounding its Whole Foods purchase could be a perfect opportunity to make a statement about its commitment to grocery and lure people to its online food business, private label products and meal kits.”

Certainly, looking through today’s Prime Day-only deals, there are a lot of grocery items for sale. Three hundred and twenty-three items, to be exact. There’s a whole page devoted to Amazon’s Prime-branded private label groceries, from trail mix to a Nutella-like chocolate spread. But as I browse the other deals—16 percent off chewable “coffee cubes,” etc.—I’m not exactly impressed. Virtually all the offerings are non-perishable, shelf-stable items. I didn’t see any fruits, veggies, dairy or meat to speak of: the kind of thing, in other words, that Whole Foods specializes in. If Amazon is supposed to be the grocer of the future, should we be worried that it’s mostly selling goods you’d want on hand in an underground doomsday bunker?

Which brings up an important point. Amazon is obviously a massive force in retail, and its competitors are understandably concerned about the Whole Foods power play. But if this year’s Prime Day is any indication, Amazon isn’t ready to inspire any grocery shock and awe. Sure, it’s mastered the crackers, candy, and coffee stocked in the interior of the store. But that’s the easy part. It’s got nothing from the perimeter—where consumers find the fresh goods they increasingly want (at least in a brick-and-mortar context).

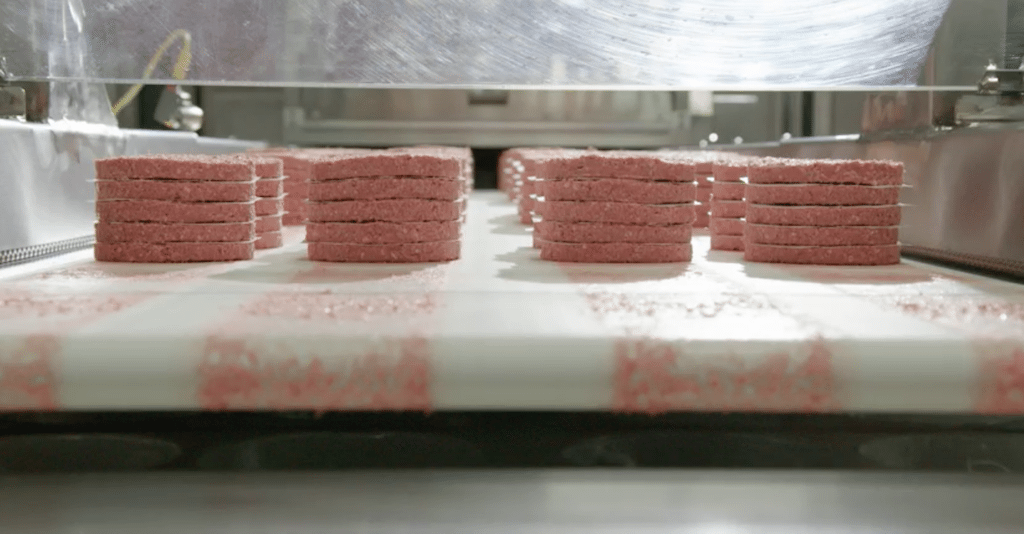

The fact is that it’s extremely difficult to deliver fresh, perishable goods on demand—especially on the kind of 2-hour turnaround that Amazon’s Prime members increasingly demand. It’s one thing when you’re dealing with crackers and canned beans. But the logistics of perishable food remain formidable, even for companies with ace technology and venture backing. Just ask Good Eggs.

Then there’s the thing most people still haven’t considered: If getting food home delivered from A to B is tricky, it’s even harder to do it safely. Yesterday, government and business leaders discussed the topic at the at the annual meeting of the International Association for Food Protection, Food Safety News reports. Rutgers University professor Bill Hallmann presented some alarming findings from his research: almost half of 160 orders of raw meat and fish arrived above the temperature—40 degrees Fahrenheit—where dangerous bacteria can start to grow. In other words: Home delivery may be convenient, but as far as food safety goes, it’s still pretty much the Wild West.

“With virtually no regulations covering virtual food sales, consumers are at the mercy of profiteers,” writes Food Safety News’ Coral Breach.

It’s worth pointing out that Walmart—a company that could benefit from stoking consumer fears about home-delivered food—was a high-profile presenter at the conference. Still, Hallmann’s a respected academic in the field, and his research—done in conjunction with colleagues at Tennessee State University—is sound. That should give us pause.

Maybe Amazon really will be the supermarket of the Internet before long, the way that we’ll buy food eventually. But unless some kinks are worked out first, that underground bunker is going to start looking pretty good.