By now, you’ve heard that a truck spilled a small sea of red Skittles—factory defects, marked without the standard white “S”—across a road in rural Wisconsin. You probably also heard that the candies were supposedly headed to a local farm for use in cattle feed. And then the plot thickened: Mars, Inc., which makes Skittles, said the plant that made the candies doesn’t sell them for animal feed.

“But wait,” much of America said. “Aren’t we burying the lede here? Cows eat freaking Skittles?”

Well, yeah—though it shouldn’t be news to anyone. It’s not an uncommon practice to adulterate cow feed with candy, one that’s been reported on before: CNN did the story in 2010, Mother Jones in 2013. Why? Plain old economics. Feed is the single largest expense in most cattle operations. So when producers find a way to blend in other, cheaper ingredients into the standard cow meal, they frequently will. As long as the stuff doesn’t hurt milk and meat output, they’re going to make more money.

In fact, a whole sub-industry has sprung up around what cows (and other livestock) perhaps shouldn’t eat, but safely can. It’s called “alternative feed.” And it gets a lot weirder than Skittles.

Before we say what’s alternative, let’s be clear about what’s standard in the diet of most meat cows and dairy cattle: unless they’re eating grass and hay, their feed usually consists of a mixture of corn, soy, and grain. But as the Skittles case demonstrates, there’s often a lot of other stuff added in.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates what cows cannot eat, and the full list, which is here, includes these highlights: “unborn calf carcasses,” “dehydrated garbage,” and “fleshings hydrolysate.” You’re also not allowed to feed cattle the meat and meat byproducts from cows and other mammals, though there are some notable exceptions: blood products, milk products, and gelatin from mammals are okay, as are pig and horse meat. Non-mammal protein sources—from fish, poultry, and veggies—are all okay, too.

If it’s not prohibited, it’s legally fair game. And that means producers have a lot of unusual options at their disposal.

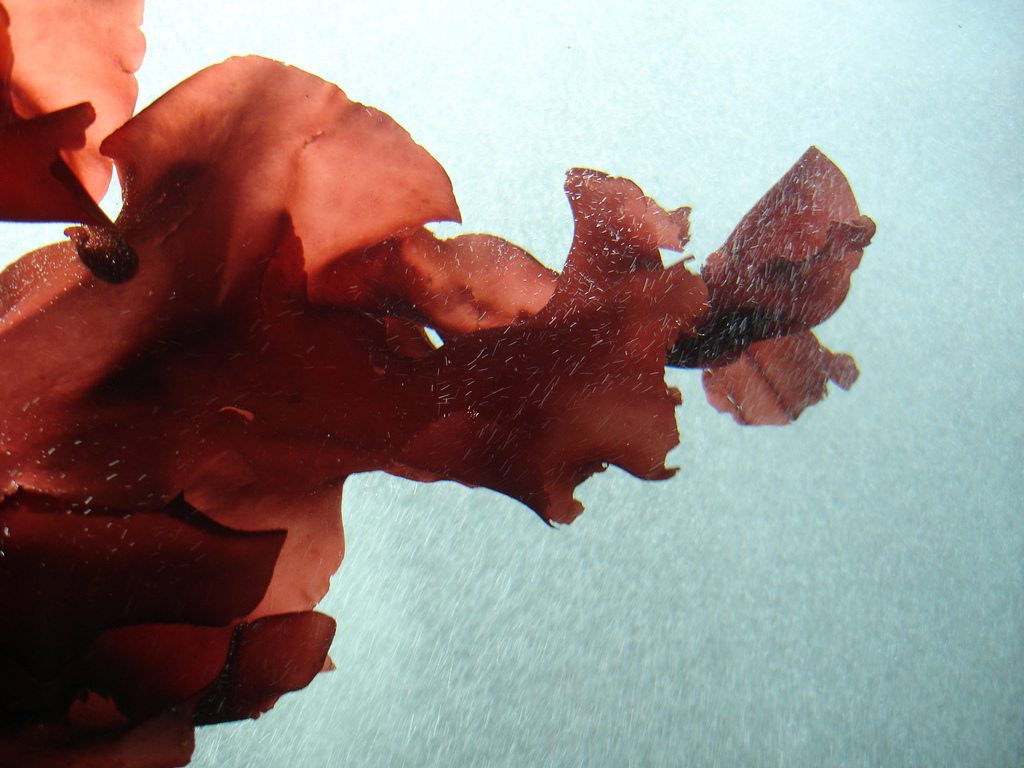

“Using Food Waste as Livestock Feed,” a primer from the University of Wisconsin-Extension, lays out the most common options. It’s quite a list: there are “spent grains” from breweries and distilleries (the stuff left over after beer and booze is made), molasses and citrus pulp, the cakes left over from soy sauce manufacture, tops of beets and carrots, soybeans hulls—even peanut skins. And that’s just the stuff from the vegetable kingdom.

Another broad category: human foods that don’t pass muster for whatever reason—like the now-infamous Skittles—and can be bought up cheap for feed. A list from the Penn State Extension includes the protein, phosphorous, and calcium content of the following alternative feeds: “Bagels,” “bread waste,” “candy,” candy product blends,” “cereal byproduct,” “chocolate,” “donuts,” “fruit twists,” and—cue the Mr. Kool voice—“Kool-Aid drink mix.” (Oh yeah.) Many of these can be purchased from suppliers like Princeville, Illinois’s Midwest Ingredients, which includes cherry juice in its list of feed additives, and the fruit fillings found in snack pies.

The strangest ingredients, though, are probably the ones derived from other animals. These are a little exotic, so some definitions will be useful.

Blood meal: “produced from clean, fresh animal blood, exclusive of all extraneous material such as hair, stomach belchings, and urine except in such traces as might occur unavoidably in good manufacturing processes.”

Hydrolyzed feather meal: “results from the treatment under pressure of clean, undecomposed feathers from slaughtered poultry, free of additives and (or) accelerators.”

Fish meal: “the clean, dried, ground tissue of undecomposed whole fish or fish cuttings.”

Meat and bone meal: is the rendered product from mammal tissues, including bone, exclusive of blood, hair, hoof, horn, hide trimmings, manure, stomach and rumen contents.

Poultry byproduct meal: “consists of the ground, rendered, clean parts of the carcass of slaughtered poultry, such as necks, feet, undeveloped eggs, and intestines.”

There’s something wonderful, strange, and unnerving about all this specificity. But I’m not laying the details out to be gross. The point is that the byproducts of the food industry, even the ones we might be squeamish about, are still edible, and we can—and do—use them to feed animals. If a factory creates a viable food byproduct that humans won’t eat, they’re usually going to be served to the animals we will.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, since the practice keeps waste materials from getting stuffed into landfills and dumped into rivers. And though some practices do have troubling public health implications—like feeding cattle chickenshit—most alternative feeds are more or less benign. So why were people so upset by the Skittles discovery? Because they believe in a vision of animal agriculture, I’m guessing, that’s based on a nostalgic fantasy. It doesn’t have to be this way, necessarily. But the agricultural system we’ve built prioritizes low input costs and maximum productivity—and, for as long as that’s true, cows will have to eat the cheapest thing on hand. Just remember that the next time a tanker of gummi worms upends on the long road to the farm.