Craig Lassig for Investigate Midwest

In Minnesota, 73 percent of water utilities with elevated nitrate are in areas that fall below the average state income. Treatment is expensive.

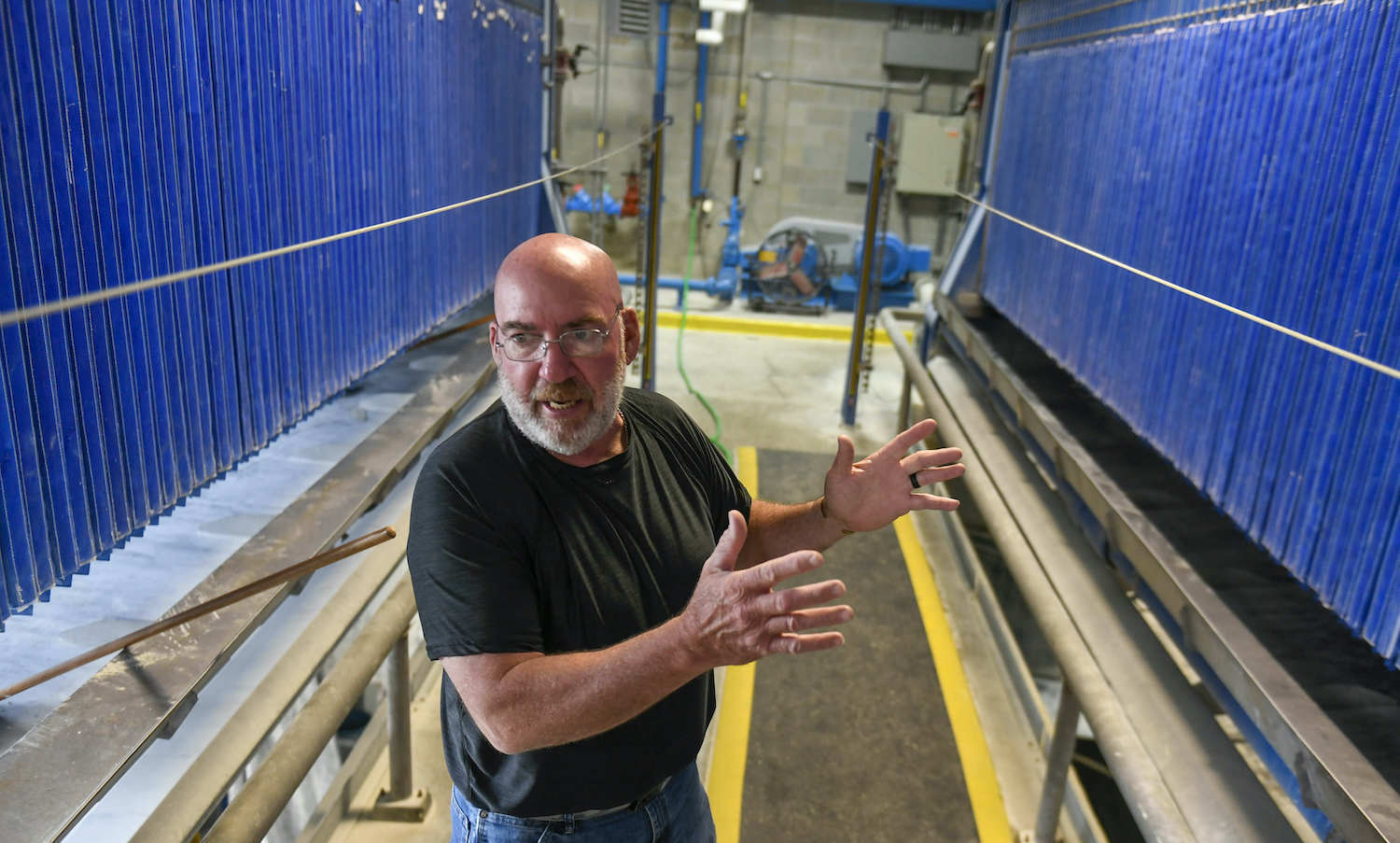

The perfect storm erupted on Doug Rainforth’s birthday.

Droughts in years prior had dried out the soil in Fairmont, Minnesota, where Rainforth manages the city’s water treatment plant. Rainforth suspects the drought concentrated both nutrients and pollutants — including nitrate left over from fertilizer — in the crop fields surrounding the small town.

This article is republished from The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Read the original article here.

Then, in 2016, the state recorded the most precipitation in its history.

What happened next is an example of the problems — and ingenuity — cash-strapped cities and counties have with protecting their drinking water from the hundreds of thousands of tons of fertilizer spread in the surrounding crop fields.

The spring rains sunk down, flushing out the stored nutrients in the soil. The nitrate-laden water then seeped into drainage pipes laid beneath the fields, which channeled the stream into nearby watersheds. Eventually, the water made its way into the chain of lakes where Fairmont sources its drinking water.

On May 19, 2016, nitrate levels spiked to more than 20 percent over the federal standard.

Nitrate is a naturally occurring compound undetectable by taste, sight or smell. When consumed in large quantities, it can affect how the blood carries oxygen, especially in infants and immunocompromised people. Nitrate is also linked to certain types of cancer.

More than 800,000 tons of liquid manure are produced each year in Martin County, the county where Fairmont is located.

By the time the Minnesota Department of Health detected the high nitrate levels and issued a warning to Fairmont water customers, Rainforth had already started pumping in water from an emergency well to lower the nitrate levels.

That day, Rainforth fielded many calls from concerned residents: mothers of infants, immunocompromised people and pet owners, all of whom were at the highest risk of negative health effects.

By July, the nitrate levels in the lake dropped below 10 parts per million, the safe standard for drinking water set by the Environmental Protection Agency. But the “perfect storm,” as Rainforth called it, had exposed weaknesses in the city’s water treatment plan.

“This plant was never meant to treat nitrates,” Rainforth said.

The future location of the temperature-enhanced bioreactor which is to extract nitrates from field runoff before the water enters the Dutch Creek watershed and reaches the lake where drinking water is pulled for the Fairmont Water Treatment Plant, July 16, in Fairmont MN.

Craig Lassig for Investigate Midwest

When the plant opened in 2013, the taste and odor of the city’s water was the main concern and nitrate hadn’t been a problem in Fairmont lakes. A system capable of removing nitrates would have cost the small city millions of dollars, Rainforth said.

Fairmont is far from unique. A study by the Environmental Working Group published on June 23 found that nitrate pollution in tap water is more likely in lower-income communities. In Minnesota, 73% of water utilities with elevated nitrate were in areas that fell below the average state income.

The average household income in Fairmont is $47,876 per year — 33 percent below the state average.

Nitrogen contamination is linked to livestock production as the tons of nitrogen-rich manure produced by animal feeding operations is used as fertilizer in crop fields.

More than 800,000 tons of liquid manure are produced each year in Martin County, the county where Fairmont is located, according to an Investigate Midwest analysis of manure management plans.

A separate EWG analysis published in May 2020 projected that farmers in Martin County applied 76 percent more nitrogen than recommended to their fields.

While livestock operations must account for nitrogen levels in the soil and in the manure when applying manure to crop fields, the manure combined with commercial fertilizer can result in too much nitrogen being applied to the ground.

A separate EWG analysis published in May 2020 projected that farmers in Martin County applied 76 percent more nitrogen than recommended to their fields.

The federal standard for nitrate in drinking water has been 10 parts per million since 1992. Newer research suggests that even nitrate levels well below 10 ppm can increase the risk of adverse health effects.

The Minnesota Department of Health closely monitors water systems with nitrate levels over half of the federal standard, said Tannie Eshenaur, water policy manager for the Minnesota Department of Health.

EWG defines any concentration below .14 ppm as protective against all adverse health effects, and anything above 3 ppm as an “elevated” nitrate level.

Anne Schechinger, who authored the study, said the communities who are most affected by nitrates are also less likely to be able to afford expensive treatment plants.

“That’s why we do this work,” Schechinger said. “Not just because it’s an added cost burden for these lower-income communities, but also because drinking this nitrate in drinking water over many years can cause health problems.”

Nitrate removal plants are expensive

When a routine test in Ellsworth, Minnesota, detected high nitrate levels, water and wastewater manager Ray Palmer drove straight to the two daycares and nursing home in town.

“We’ve got a problem,” he told the staff.

Ellsworth is a town with a population of fewer than 500 people in Nobles County, one of Minnesota’s largest livestock-producing counties. Located just a mile from the Iowa border, the city’s water largely comes from shallow wells. The average yearly household income is about $26,000 below the state average.

The city has battled nitrates for decades and its nitrate removal plant has been running since 1994.

Every few years, the materials used to filter the water wear out and need to be replaced, Palmer said. The last time that happened was in 2016, Palmer said, and a testing error in 2019 also resulted in a violation of the nitrate standards.

The city purchased bottled water for the affected facilities, then paid around $9,000 for new filters in the plant, Palmer said.

But nitrate removal plants don’t remove all of the compound. In Ellsworth, which has operated a nitrate removal plant since 1994, the nitrate level is usually between 4.1 and 4.6 parts per million, Palmer said.

An agitator mixes lime with the water to soften it while the treated water is skimmed off the top in the clarifier room room in the Fairmont Water Treatment Plant, July 16, in Fairmont MN.

Craig Lassig for Investigate Midwest

Ellsworth City Clerk and Treasurer Dawn Huisman said the city doesn’t track the cost of nitrate treatment per resident. The city spent approximately $42,400 on the water department in 2020, according to the city budget.

A 2018 study by Schechinger and her EWG colleague Craig Cox used a formula developed by University of California-Davis researchers to estimate the per-person cost of nitrate removal plants.

Schechinger and Cox found that in small communities, the potential cost of building and operating a nitrate treatment plant ranged from $47 to $378 per person per year.

A 2015 report by the Minnesota Environmental Quality Board found, in the most extreme cases, obtaining the needed nitrate treatments would cost thousands of dollars per household.

In Hastings, Minnesota, a nitrate removal plant cost $3 million to construct and yearly upkeep costs range from $100,000 to $130,000, Hastings public works department director Nick Eggers said. The Hastings nitrate removal plant is connected to two wells with historically higher levels of nitrate.

“We’re not intending on building another treatment plant unless we absolutely have to.”

But the city’s other four wells without nitrate treatment have spiked up to 8 or 9 ppm of nitrate, Eggers said.

“We’re not intending on building another treatment plant unless we absolutely have to,” Eggers said. “I don’t think any community wants to have that if they can avoid it.”

Instead, the city is managing nitrate levels in these wells by working with county officials on promoting conservation and responsible agricultural practices in the areas surrounding wellheads and watersheds.

Eshenaur, with the state health department, said the cost of removing nitrate from private wells is also a health equity issue. Landowners who deal with high nitrate levels in their personal wells have to buy an in-home reverse osmosis treatment system, which cost hundreds of dollars.

Groundwater protection as a more cost-effective option

Preventing nitrate from entering drinking water sources is often more effective and less expensive than removing nitrate from the water, said University of Minnesota researcher Joe Magner.

Magner is working on the Dutch Creek Watershed project with Rainforth and others, and has done similar work in Iowa and Indiana.

A wellhead conservation plan took effect around 2010 for the wells surrounding Ellsworth, Palmer said. City and county officials worked with farmers to ensure that fertilizer would not be spread on the land immediately surrounding wells, reducing the amount of nitrate in the soil.

“We really think that farms that contribute the most pollution to this nitrate drinking water problem need to be required to implement conservation practices on their fields.”

It took about 10 years for the results to pay off, Palmer said. Before the wellhead conservation program, the water coming into the treatment plant was more than three times the allowable concentration of nitrate.

Now, the raw water comes in around 13 ppm — just 3 parts per million over the standard — before the treatment process.

But wellhead and groundwater protection agreements like the one in Ellsworth are voluntary for farmers and conservation practices aren’t being adopted fast enough to combat rising nitrate levels, Schechinger said.

“We really think that farms that contribute the most pollution to this nitrate drinking water problem need to be required to implement conservation practices on their fields,” Schechinger said.

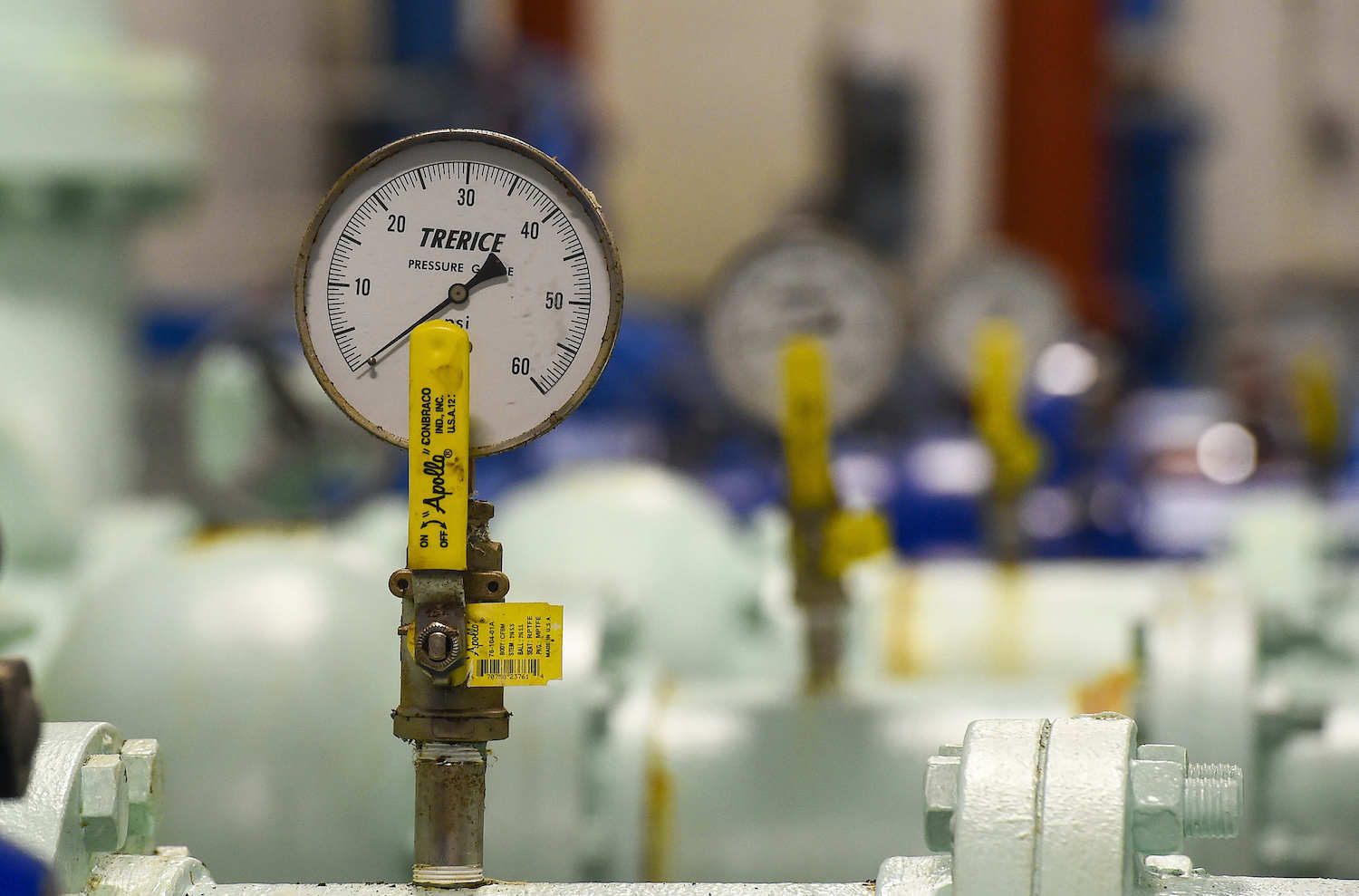

A vast array of pipes, valves and control boards monitor and control the water as it flows through different parts of the plant in the Fairmont Water Treatment Plant, July 16, in Fairmont MN.

Craig Lassig for Investigate Midwest

Conservation practices that reduce nitrate contamination can include setting aside land that borders a well, planting cover crops on fields in between corn and soy rotations, and using fertilizer that releases nitrogen slowly.

This fiscal year, Minnesota set aside more than $15 million for watershed protection and restoration.

The city of Fairmont is taking similar steps to protect its lake. A nitrate treatment plant doesn’t make sense for the city both because of the cost and the nature of the city’s water supply, Rainforth said.

The nitrate levels depend heavily on the time of year and the weather, in part because the city uses surface water rather than wells. In 2016, the “perfect storm” created the conditions for the nitrate level spike. Currently, the nitrate concentration is below 1 ppm.

But the city needed a plan to address additional spikes in the future. So they focused on the main source of nitrate: the Dutch Creek Watershed.

It’s an unassuming creek that meanders past corn and soy fields on the outskirts of town. But it collects nitrate from field runoff and carries it into Budd lake.

After the 2016 nitrate spike, Rainforth met with representatives of the city of Fairmont, the County Water and Soil Conservation district, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, the University of Minnesota and MN Department of Ag to discuss how to address the problem of the Dutch Creek Watershed.

A line of process sample taps brings in water samples from different parts of the plant in the Fairmont Water Treatment Plant, July 16, in Fairmont MN.

Craig Lassig for Investigate Midwest

Researchers suggested a temperature-controlled nitrate bioreactor.

Nitrate bioreactors are essentially large pits of woodchips placed in areas with high runoff. A microorganism in the pit converts the nitrate in the water into nitrogen gas, which is released into the air.

But this natural reaction is most effective at temperatures higher than 50 degrees Fahrenheit. That presents a problem in the Upper Midwest, where spring rains can push nitrate into water sources before the average temperature reaches 50 degrees and the nitrate-removing reaction kicks in.

By placing a greenhouse-like structure over the bioreactor, researchers hope to warm up the pit so the nitrate removal can begin earlier in the year.

The project was funded with a $175,000 grant from the state Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund.

“It’s sad that there’s still a lot that I think is held up on the hope that people will do the right thing, especially in areas where we can’t enforce anything.”

It would be the first of its kind in the Upper Midwest, and if it works, could be a step forward for other small communities in the northern United States.

In addition to the bioreactor, the Martin County Water and Soil Conservation District is encouraging farmers to adopt nitrogen-saving practices outside the city limits. Similar efforts are underway in the counties surrounding Hastings.

The Biden administration is also pushing for collaboration between local governments and landowners to increase the amount of conserved land and promote the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, such as cover crops.

“It’s sad that there’s still a lot that I think is held up on the hope that people will do the right thing, especially in areas where we can’t enforce anything” Eggers said. “We’re just asking nicely and trying to make land users aware that, ‘Hey, the types of practices you may have in managing your land could impact this population downstream.”

Ignacio Calderon contributed the graphic to this story.