Cow farts are having a bit of a moment. In February, Bill Gates called them one of the world’s biggest problems. The same month, Democrats unveiled the Green New Deal, releasing a draft version of a fact sheet that explicitly addressed bovine flatulence. Scientists are quick to note that the main source of pollution caused by cattle is burps, not farts, but it doesn’t seem to matter. The shorthand persists.

It’s not the farts or the burps that are the problem, really. It’s the greenhouse gas they release: Methane has 25 times the environmental impact as carbon dioxide, and the average cow releases 330 pounds of it per year. And according to the Environmental Protection Agency, agriculture is responsible for a third of the methane released into the atmosphere in the United States. (The largest source of methane, Vox points out, is leaks in the natural gas infrastructure. Last month, the Trump administration announced rollbacks on Obama-era regulations requiring energy providers to monitor and fix their equipment.) Cattle and their burps have played a major role in conversations about meat and climate change.

It’s not clear what Bovaer is made from, nor do we have many details about how it works. The company did not respond to an interview request. But DSM claims that adding ¼ teaspoon of whatever it’s marketing to a cow’s feed each day “suppresses the enzyme that triggers methane production in a cow’s rumen,” according to a press release. The product has been under development for a decade, and the company claims it’s the most extensively studied solution for burped methane to date. Translation: This may be the best thing we’ve got right now.

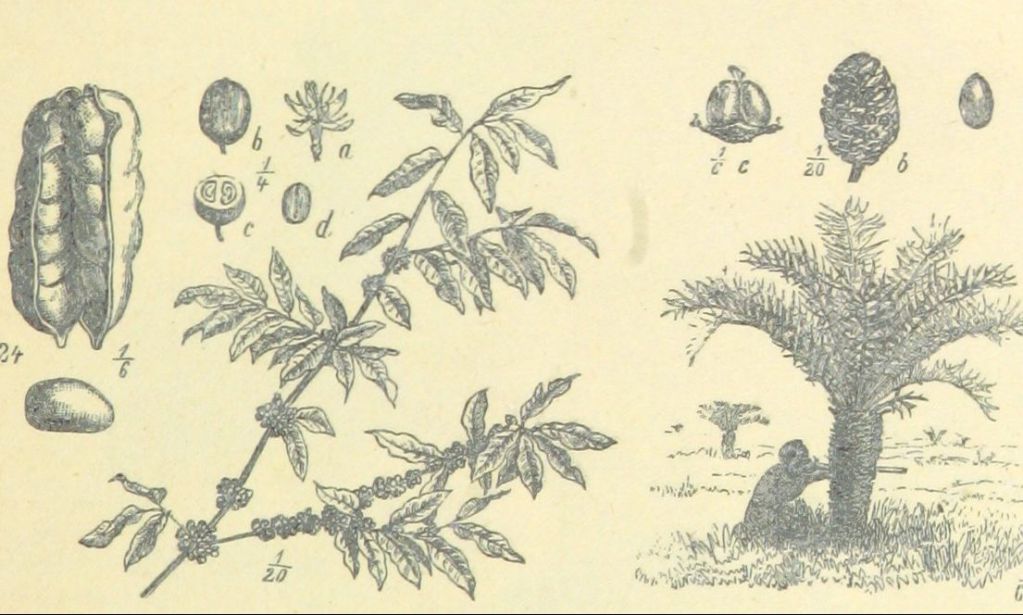

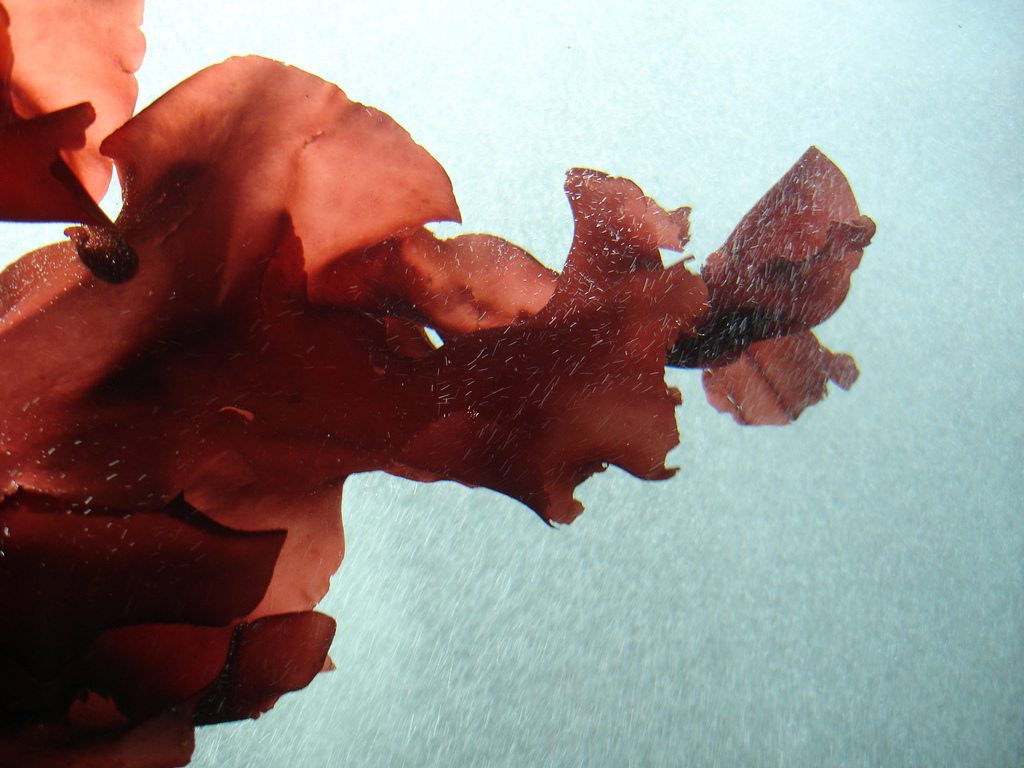

In the U.S., seaweed has shown some promise as a methane-reducing food additive, too. As we reported in 2017, preliminary evidence indicated one variety could reduce methane production by up to 99 percent. (A more recent study, published by researchers at Penn State this summer, claimed a more conservative 80 percent reduction.) Scientists haven’t yet answered questions about whether or not seaweed would work as a food additive over the long term—we don’t know, for instance, whether or not it impacts the taste of a cow’s milk, or whether seaweed’s active compounds (bromoforms!) would survive the processing and storage necessary to make it feasible for farmers in the Midwest.

Also, it’s not clear that cows will actually eat it. Apparently, it doesn’t taste great. Once it hits about 0.75 percent of an animal’s diet, the animal starts eating less. Even if all these issues were resolved and farmers everywhere wanted to start their herds on a seaweed-heavy diet today, they likely couldn’t. There simply isn’t enough Asparagopsis taxiformis growing on the planet to feed every single cow a little bit every day.

Once it’s released, dairy companies will have all kinds of incentives to foot the Bovaer bill on behalf of their farmer-suppliers. Reuters points out that Nestle wants to zero out its greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, and Danone wants to halve its carbon dioxide emissions by 2030. If these companies are serious about reducing emissions—and if they see their future business as meat and dairy, which is not a given—they’ll have to put their money where their mouth is.