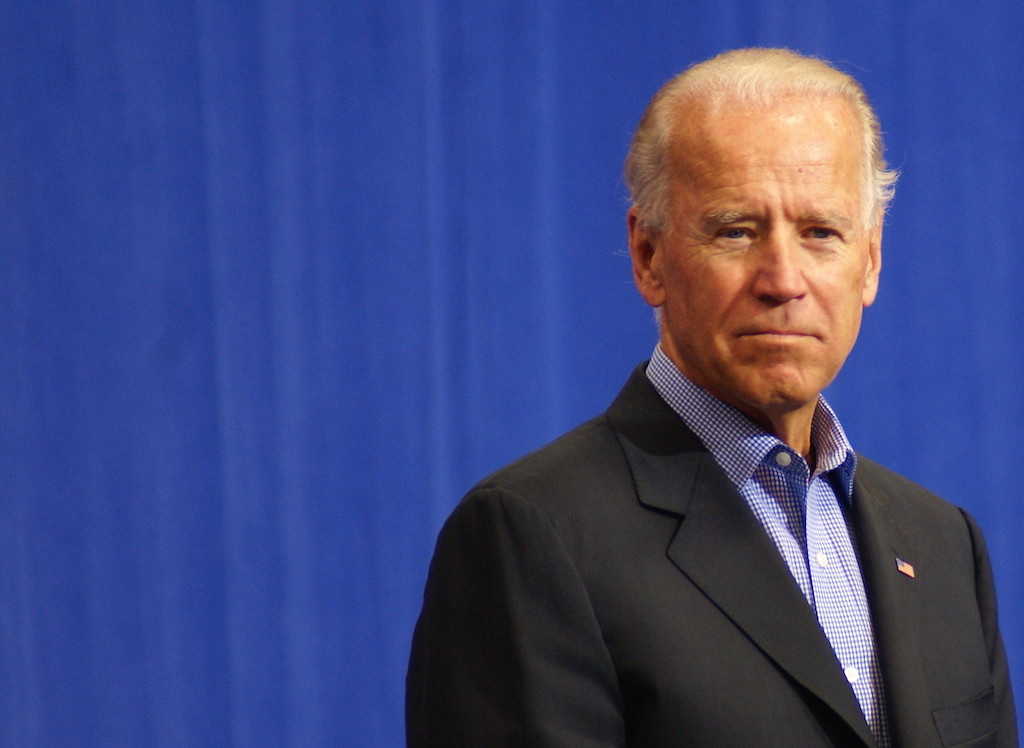

Vice President and 2020 presidential hopeful Joe Biden has released his plan for rural America. Key goals include reaching net-zero emissions in the agricultural sector and ensuring access to healthcare for all. The rollout comes three months after other front-runners for the Democratic presidential nomination met in Iowa to discuss their plans for the future of farming.

At this point, several Democratic presidential contenders have released some sort of vision for the future of the country’s breadbasket. Senator Elizabeth Warren came out with a package of proposals in late March, pledging to tackle agribusiness consolidation as her top priority. Her plan relies on breaking up the big ag companies to level the playing field for smaller-scale farmers. Senator Bernie Sanders followed with a similar proposal in May. By contrast, Biden’s position on antitrust enforcement appears much more moderate: it’s the sixth bullet on the list, and he just says he’ll “strengthen” the Sherman and Clayton Antitrust Acts and the Packers and Stockyards Act.

As of this week, four Democratic candidates lead the polls: Biden, Warren, Sanders, and Senator Kamala Harris, who has not yet released a comprehensive policy platform for agriculture or rural America. The Iowa caucuses are on February 3, and the nomination will be finalized next July.

So far, the frontrunners seem to agree on a few things. Trade deals need to better support American agriculture. Small-scale and beginning farmers could use a boost. Farmers who grow chickens under the contract system are getting screwed. Seed and chemical companies have too much power. Rural America needs broadband internet.

But the devil’s in the details. Generally speaking, Biden’s platform seems to favor incentivizing positive change rather than overhauling existing policy. For example, all three candidates seem to agree that a handful of agribusinesses should not control the entire seed industry. Sanders wants to reform patent law to ensure that farmers can’t be sued by Bayer (which recently acquired Monsanto) and Warren says she’d reverse the Bayer-Monsanto merger. Yet Biden prefers to increase funding for land-grant universities so new developments in seed technology will be owned by the public.

Similarly, all three policy proposals make mention of the meat industry’s contract farming system, which critics say traps chicken growers in debt and cedes too much power to vertically integrated meat production companies like Tyson and Cargill. But where Warren pledges to “prohibit abusive contract farming” and Sanders would place a moratorium on vertical integration of agribusinesses, Biden settles for a promise to “strengthen” enforcement of the Packers and Stockyard Act, the century-old legislation that promotes fair business practices in the meat industry. (Longtime NFE readers will recall that the Obama Administration was criticized for dragging its feet on a set of rules that would have strengthened this legislation; the Trump administration later rolled them back before they ever took effect.)

There are a few other notable differences among the three platforms: Both Warren and Sanders committed to supporting right-to-repair laws, whereas Biden made no mention of them. Right now, companies like John Deere can prevent farmers from fixing their own equipment, driving up the cost of repairs on tractors that can already cost more than $300,000. And where Warren and Sanders both expressed explicit support for Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) laws, legislation which would mandate that meat be labeled according to where it was grown, Biden’s plan is silent on the issue. (As Civil Eats notes, he has supported COOL laws in the past.)

Biden’s vision contains a few priorities that are absent from his competitors’ proposals, too. Most notably, he wants to make American agriculture the first in the world to achieve net-zero emissions, and he plans to do so by expanding the existing Conservation Stewardship Program. Neither Sanders nor Warren have explicitly addressed agricultural emissions in their rural policy proposals. Biden’s plan is an incentive-based program that pays farmers for adopting conservation measures. Biden also wants to boost regional food systems, and he plans to get there by supporting the development of small-scale supply chains that allow small-scale farmers to sell to institutions. How he intends to achieve this goal, however, is very much unclear at this point.

Of course, everything may change in the months leading up to the primary. Candidates like Biden who have relied on vague language in their proposals may be forced to crystallize their positions on issues like antitrust enforcement over the course of the campaign, as is already happening with healthcare.

One issue we’ll be paying attention to is Democrats’ support for ethanol, the corn-based biofuel that, according to Politico, pours $5 billion into Iowa’s economy each year. It’s fallen out of favor among environmentalists in recent years, and Bloomberg reports candidates are hearing from anti-ethanol activists at rallies and in town halls. Biden expressed explicit support for ethanol in his platform; Sanders was initially a critic during the 2016 primaries but reversed course after campaigning in Iowa. No Democrat has come out against ethanol in the current campaign cycle.

Biden’s plan already has the support of former Iowa governor and former Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, who has still not explicitly endorsed Biden (or any other candidate).

It’s unlikely we’ll hear much about agricultural issues in the Democratic debates, as healthcare and immigration have thus far dominated the airwaves. If 2016 was any indication, that’s not likely to change. And if a Democrat is elected, he or she will still likely face an uphill battle. The Obama campaign’s priorities looked very similar to these: He pledged to strengthen antitrust laws, limit subsidies for agribusiness, and regulate pollution from large livestock operations, none of which actually happened during his tenure.