This story was published in partnership with The Intercept.

On Wednesday morning, after a closed-door meeting that lasted much of the night, both houses of Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled state legislature passed a comprehensive set of measures limiting the incoming Democratic administration’s power. The consequences of the many provisions are still coming into focus. Buried under controversial moves to curtail early voting and strip authority from Gov.-elect Tony Evers is a sweeping codification of welfare restrictions that Republicans across the country have long sought.

The new legislation enshrines in state law outgoing Gov. Scott Walker’s controversial policy of forcing food stamp applicants to submit to drug testing. It also limits the incoming administration’s ability to walk back the state’s strict new work requirements for aid recipients. After Walker’s approval, Wisconsin will be the only state that requires drug testing for many non-felon food stamp applicants.

The bill appears to defy federal policy regarding the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, as the food stamps program is now known. The United States Department of Agriculture does not allow states to impose certain eligibility limits, like drug testing, on SNAP applicants without explicit permission. Walker sued the Obama administration for permission to implement drug screenings back in 2015, but a judge threw out the lawsuit on procedural grounds. Walker then sought permission from the incoming Trump administration in 2016, but his letter went unanswered. (Leaked emails in April of this year showed USDA was considering allowing states to implement drug testing, but such a policy has not yet been announced.)

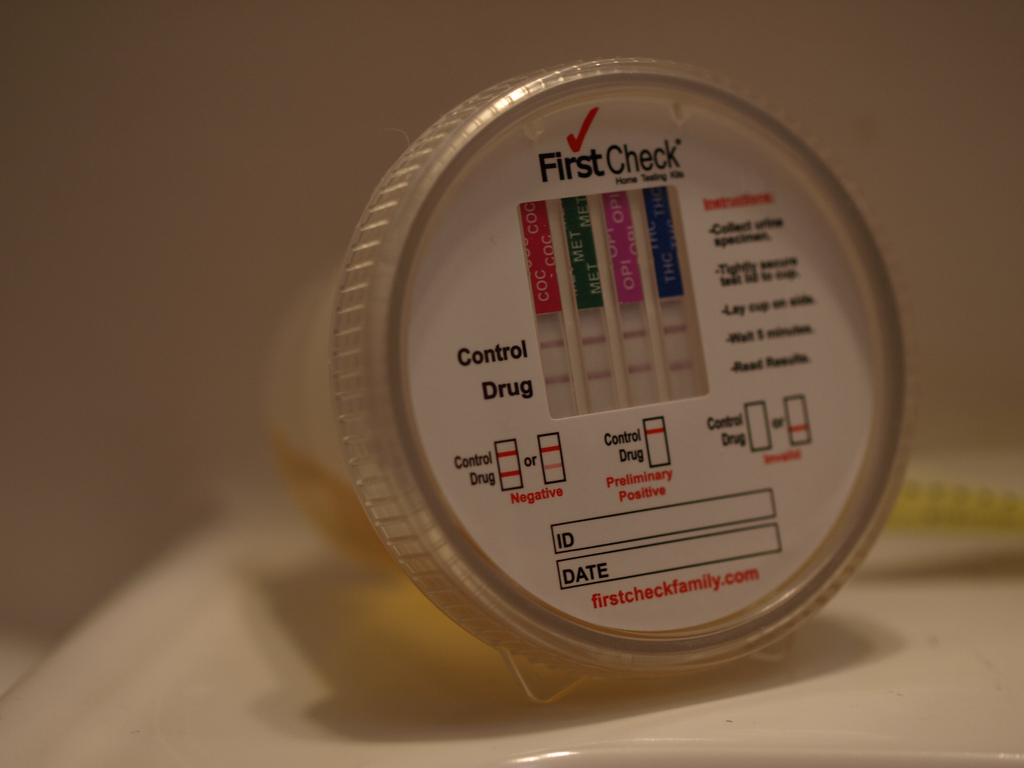

Lacking federal permission, the Walker administration announced a workaround in December of last year: an administrative rule requiring drug screenings only for participants in the state’s Employment and Training Program. (The specific process involves a preliminary screening followed by testing in some cases.)

Effectively, however, this move instituted drug screening for all unemployed food stamp recipients: Wisconsinites hoping to stay on food stamps for longer than three months are required to either prove employment or enroll in the training program in order to keep their benefits. If participants fail to find work or enroll in the program, the consequences are severe. They’re banned from receiving food stamps for nearly three years. The USDA has not intervened to block this policy, but it is expected to face legal challenges.

Tens of thousands of those people live in Milwaukee County, where Sherrie Tussler works as executive director of Hunger Task Force, a food bank. “We’re torturing poor people in the Dairy State, and we’re doing it with intent and doing it with malice,” she said. Tussler called Wisconsin’s system a “giant government boondoggle,” where access to aid is difficult even for applicants who closely follow the many rules. “The biggest battle is proving to the state that you did the work requirement,” she said.

These two policies—drug testing and work requirements—will work in tandem to deny more people food stamp access in Wisconsin. The new work requirements, arguably the most severe in the nation, will send people to the employment and training program in droves. All those people will be required to submit to drug tests if they want to keep their benefits. And now, neither of these policies can be undone by a future administration. They have to be repealed by law.

Since Walker began implementing work requirements in 2015, the number of food stamp recipients in Wisconsin has plummeted by nearly 20 percent from 800,000 to 650,000, according to the Washington Post. This new legislation virtually ensures that decline will continue, even as voters rebuke the state’s Republican Party.

Wisconsin functions as a test case for the Trump administration’s agenda on welfare reform. With its strict work requirements and embrace of unproven employment training programs, its recent reforms align closely with provisions the Republican House of Representatives tried unsuccessfully to tack onto this year’s Farm Bill.

The broad appeal of Wisconsin’s approach among Republicans is largely ideological. “It stigmatizes benefit receipt,” said Elizabeth Lower-Basch, a director at the Center for Law and Social Policy. “It’s designed to reinforce the stereotype that people need help because of their poor personal choices as opposed to an economy of low wages and unstable jobs.”