Since it was first confirmed in China in August of 2018, highly contagious African swine fever has spread to every province in the country, then to Vietnam, Mongolia, and Cambodia, and is now rumored to have reached North Korea. The disease, which poses no threat to humans, has had such a devastating impact on the country’s hog supply that some estimates show China could not replace its lost pigs even if it imported every single animal available for export.

Thus far, the spread has been kept out of the United States—but some veterinarians and industry insiders are wondering if its arrival here is inevitable.

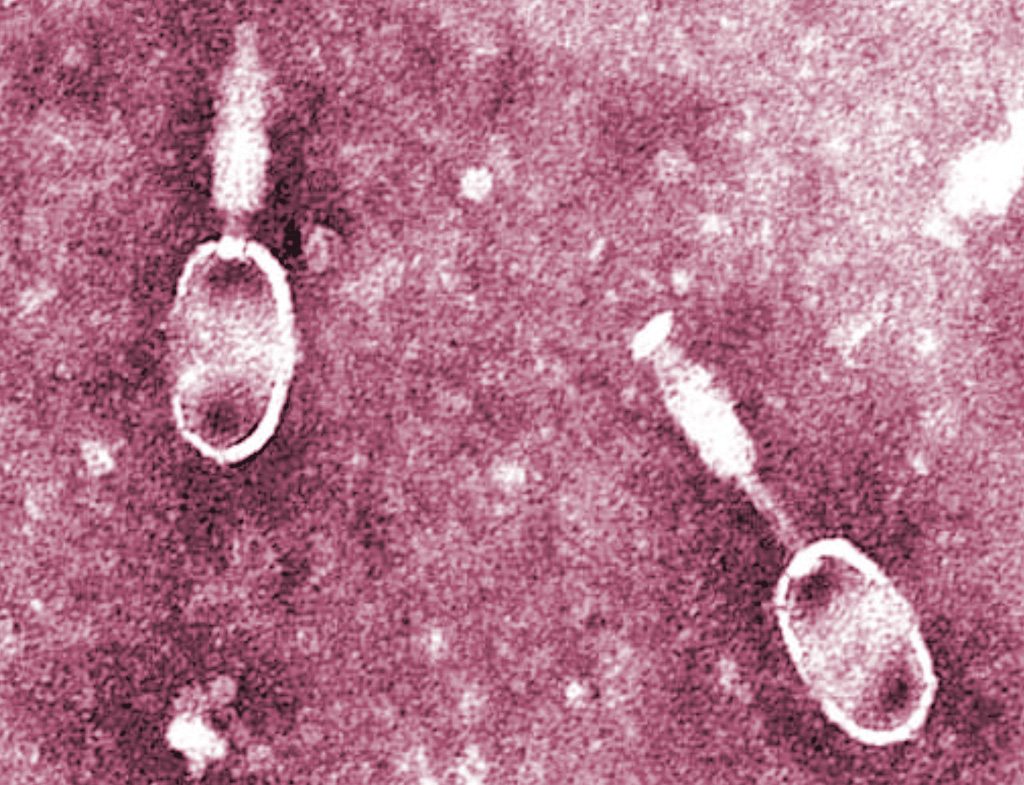

African swine fever (ASF) is highly contagious and there is no cure. Infected animals develop high fevers, bloody diarrhea, and skin lesions, and most die within days. So far, the only effective means to stop its spread is to cull entire herds. Official April statistics from China showed that more than 1 million animals had been culled nationwide, and the government’s estimates are believed to be vastly underreported. An analysis from RaboBank projects that up to 200 million pigs could be culled or die as a result of the country’s outbreaks.

Classical swine fever., as illustrated in 1913 for the Department of Agriculture

China’s outbreaks have so far been a boon for U.S. pig farmers. The Wall Street Journal reports pork exports to the country have surged in the past few weeks despite high tariffs. If the disease is detected on American farms, those gains will disappear overnight. One estimate pegs losses at $16.5 billion in a single year if U.S. herds are infected.

North American farmers and regulators have taken serious precautions to ensure that doesn’t happen. ASF can be transmitted through infected meat, between pigs, and on surfaces like shoes and clothing. In the U.S., Customs and Border Patrol seized a million pounds of products containing processed pork at a port in New Jersey in March. The National Pork Producers Council canceled the 2019 World Pork Expo, which would have drawn 20,000 visitors from around the world to Des Moines, Iowa, for fear of spreading the disease. And on Monday, National Hog Farmer reported that trade teams with the U.S. Grains Council will not visit U.S. swine farms in 2019. The USDA has also increased the number of beagles used to detect contraband meat in travelers’ luggage.

Yet Dr. Scott Dee, a veterinarian for Pipestone Veterinary Services in Minnesota, says the threat of ASF continues to keep him awake at night. He worries the virus will be carried into the U.S. by way of animal feed ingredients imported from ASF-positive countries. “If we don’t change how we’re handling the feed risk, the chances [of seeing ASF on U.S. soil] are very, very high,” he says.

Dee has been researching ASF’s ability to survive the month-long journey across the ocean in shipments containing feed ingredients. He explained in a phone interview that the virus can be transmitted through dust on farmers’ shoes and clothing, adding that harvested grains are sometimes dried on the open road, thus increasing the risk of contamination. He says Pipestone’s China-based vets have confirmed to him that air-drying is a regular occurrence, adding that the U.S. imported nearly 80 million kilograms of soy from China in 2014, the last time he calculated the numbers using the U.S. government’s harmonized tariff schedule, a tool that tracks imports.

Dr. Liz Wagstrom, chief veterinarian for the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC), says it’s difficult to determine where soy imported from China winds up after it leaves U.S. ports. “It’s hard to even identify whether it’s coming in for human use. Like, is it soybeans for edamame, soy for tofu? Or is it soybean meal for animal feeds? Of the animal feeds, it appears that some of the soy coming in is considered organic and it is going into the organic poultry and dairy [industries] in a large part. That’s what we’re surmising—I don’t know that we actually know that for sure.”

I called a few different swine feed mills in the Northeast and the Midwest, and all of them said they rely exclusively on domestic grain, even if they do use some supplements manufactured in ASF-positive countries. No one I talked to could point toward any mills that relied on Chinese soy imports.

Here’s the thing: Pig feed contains tons of ingredients. They’re mixed at a mill, then distributed to individual farms. One 2018 analysis found that inventory at a midwestern swine farm included ingredients from 12 countries in North America, Asia, and Europe. So even though it’s hard to find confirmation of Dr. Dee’s contaminated soybean hypothesis, it’s entirely possible that other ingredients might make their way from ASF-positive countries to U.S. farms. And, crucially, it might not be the ingredients themselves that matter the most: The trucks and packaging that carry them may also be capable of spreading disease.

Dee thinks artificially manufactured feed ingredients, like pet food or a supplement called choline, pose a lower risk of on-the-ground contamination than soybeans dried in the open air. But his research has shown that the virus can survive in these ingredients, too. In 2018, Dee published a paper in PLOS One in which he simulated the conditions in a shipping container. He found that African swine fever could survive for a month in most of the ingredients he tested. It’s particularly hardy in liquids.

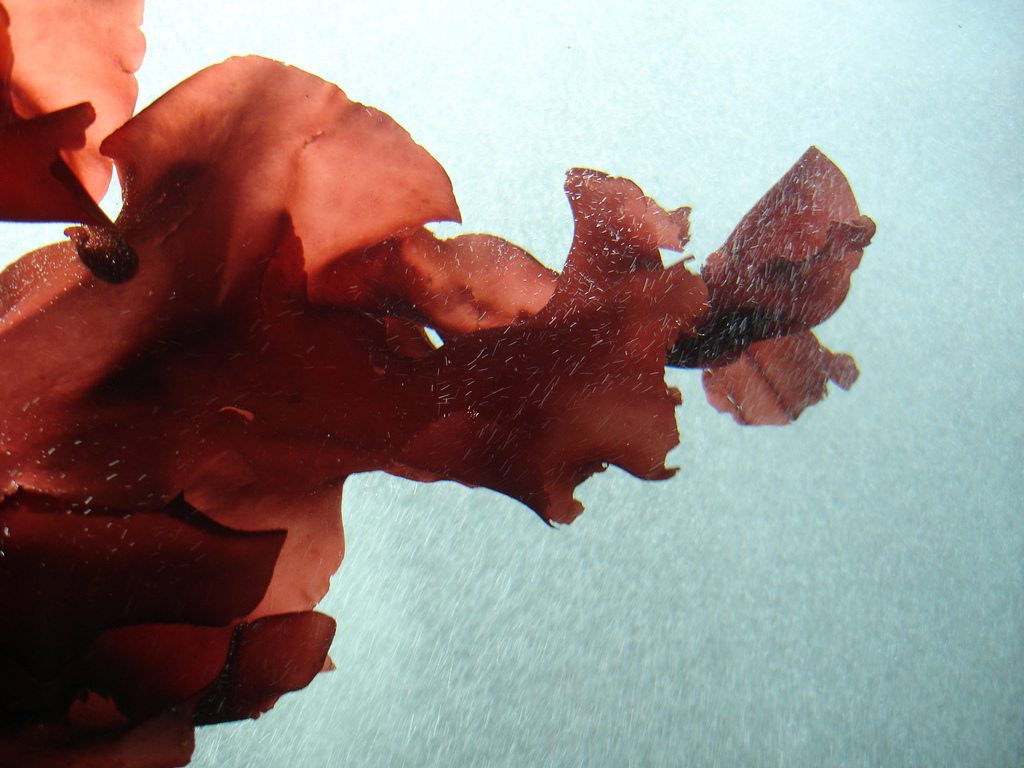

Woven feed bags like this, used for ocean transport, may be at risk for transporting ASF

In 2013, when an outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDv, which is unrelated to ASF) killed about 8 million pigs, the United States Department of Agriculture suggested that PEDv had entered the country on giant, woven tote bags used to carry feed materials across the ocean. The bags, which can hold up to 3,000 pounds, may have been contaminated before they were shipped. The virus was then spread to distribution companies, then to feed mills, and finally to individual farms. Another evaluation the following year reached the same conclusion. Unlike feed ingredients, these bags don’t fall under strict regulations and testing requirements. A bag that was used to deliver grain to a contaminated farm and subsequently re-used on a container ship to the United States could negate even the most meticulous biosecurity measures at farms or factories.

The NPCC’s Wagstrom emphasizes that we don’t know for certain how PEDv wound up in the U.S. “It’s very close to what was in China. There was [some] thought it could have been tote bags, and there was [some] thought it could have been travelers, but I think we’ve got very strong evidence that once it got into the United States, feed was one of the vehicles that helped spread it,” she says.

Still, scientists have established that ASF can survive in feed shipments. They’ve also recently established that it can make the transition from feed to animals. Dr. Megan Niederwerder, a researcher at Kansas State University, has established that animals are particularly vulnerable when they’re repeatedly exposed to the virus, as would happen if they eat over and over at a trough or water bowl containing contaminated feed.

So what can farmers do to protect their herds from ASF? The National Pork Board has published a decision-tree matrix producers can use to assess feed ingredient safety. It encourages them to ask their feed suppliers about where their ingredients come from, and to ask ingredient manufacturers about their biosecurity practices.

Food Ingredient Safety Matrix

Right now, Dee says, it’s not feasible for the U.S. hog industry to stop all imports of feed ingredients from ASF-positive countries. It’s difficult to find some additives, like choline, anywhere else. Wagstrom adds that ceasing soy imports from countries with the disease might have a negative impact on U.S. trade relations across the board. In the meantime, feed mills are quarantining some ingredients. A spokesperson for Hubbard Foods, a subsidiary of AllTech, says they keep risky ingredients in a temperature-controlled warehouse for 30 days before integrating them into feed mixtures. A spokesperson for Crystal Valley Co-op added that they quarantine ingredients for 45 days.

All of these measures are currently voluntary. “Actually, at this time we have nothing mandatory within the United States [related to ASF mitigation] for non-animal feed products,” Wagstrom says. Canada, by contrast, recently began requiring that all imported grains headed inland have documentation certifying that they have undergone either heat treatment or a period of quarantine.

Dee thinks the U.S. should implement restrictions similar to its northern neighbors. But Wagstrom isn’t sure that’s feasible right now—Canada just has six ports, while the U.S. has many more. “We’re basically looking to develop something that (one) is based on the best-available science—we have an emerging body of knowledge around the issue, (two) is achievable, and (three) has the least potential to minimize or disrupt trade with other trading partners,” she says.

Dee is adamant that the U.S., Mexico, and Canada need to collaborate to combat ASF. “If one gets it, we’re all screwed,” he adds. This week, Canada is hosting an international forum on the virus.

Wagstrom has more faith in the control measures that have already been implemented, like voluntary quarantines. “I have a great deal of concern [about ASF entering the country] because it’s such a high consequence, but I also have a lot of confidence that a lot of the barriers we’ve put into place are helping us keep it out,” she says. “I know that’s kind of a wishy-washy answer, but I’m not one of those people that will say it’s just around the corner. We’re doing good work to keep it out.”