U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center

The soil on American military bases is about to get healthier. That’s thanks in part to new research on the benefits of a very unique kind of compost: finely shredded government documents. The concept, published in a September report by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is aimed at doing two things: reducing the amount of paper waste that ends up in landfills, and improving the condition of military training grounds.

The National Security Agency maintains strict rules on how classified documents must be destroyed, requiring that paper shreds measure no more than 0.2 square inches. That’s because simple strip-shredding is far from foolproof and is vulnerable to reassembly both by advanced software and people with stamina.

The shredding guidelines may protect state secrets, but they pose another problem. Once shredded, paper becomes too fine to be processed in recycling facilities.

U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center

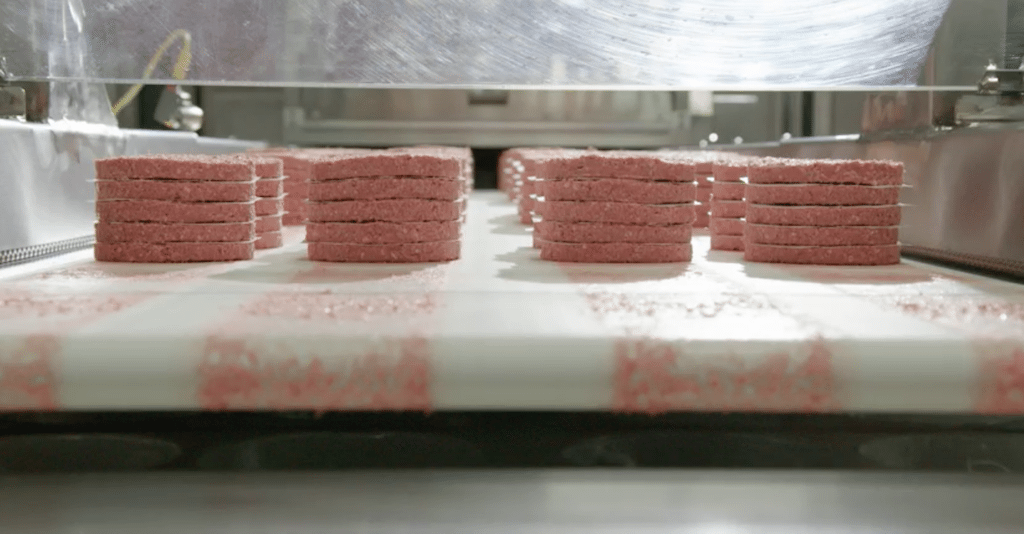

U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Approximately 1 ton of pulverized paper is stored in the rented rolloff container.

“[Shredders] grind paper to the point where it’s no longer useful for recycling. They break the fibers down,” says Henry Allen Torbert, a soil scientist with the Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s agricultural research service involved with the report. “The normal process of getting rid of used paper is to recycle it, but [the military] can’t do that. And so it all goes to landfill.”

Meanwhile, the Department of Defense (DOD) has long grappled with a separate issue—soil degradation. Military grounds across the country are suffering from erosion caused by decades of training, both on foot and by vehicle.

Now, researchers have figured out a way to turn all of the military’s paper waste into a carbon-rich compost that improves soil health and supports the growth of native vegetation.

The study commenced in April 2015 at Fort Polk, an army installation in Louisiana. At the beginning of the multi-year experiment, researchers raked varying amounts of shredded classified paper into two separate sections of common soil, one with high fertility and one with low fertility. Next, they “disked” the soil surface, a technique that drove the compost deeper into the ground, and took measurements from each plot of land to determine baseline chemical composition and contaminant levels in the soil.

They also included standard practice blocks of land that received only a typical treatment of fertilizer and lime and control blocks that received no inputs at all. After they—quite literally—laid the groundwork, the researchers planted various perennial native grass seeds on the plots by hand and monitored plant growth over time.

Then, in October 2016 and again in October 2017, the team measured plant cover—that is, the area of soil covered by weeds and planted grasses—and vegetation biomass, which they measured by drying and weighing vegetation clipped from randomly selected sections of each soil block.

Here’s what they found: The low-fertility soil that received the most paper compost saw more plant cover compared with both the control treatment and the standard practice treatment—by 42 percent and 17 percent, respectively. This means that adding shredded paper to soil increased the amount of acreage covered by plants, which is an important and effective way to protect against erosion. Meanwhile, the control treatment and standard practice treatment saw higher rates of weeds among total plant cover.

Results were even more striking in the case of the high-fertility soil type. On the plot that received the greatest volume of paper compost, plant cover was 48 percent greater compared to the control soil that received no treatment, and 62 percent greater than the soil that received the standard application of fertilizer and lime.

Results regarding plant biomass—that is, the weight of vegetation on a given block—were a bit more complicated. For the more fertile soil type, compost increased plant mass. However, in the case of the less fertile soil type, biomass actually decreased when compost was applied.

And that’s because the researchers learned something after they first applied compost to infertile soil that then changed their approach for the fertile soil.

Torbert says he believes that too much compost may have played a role in the disparate results. For the plot of less fertile soil, which researchers added compost to first, they added it in the following amounts: 18 megagrams, 36 megagrams, 54 megagrams, and 72 megagrams per hectare. (One megagram is equivalent to 1,000,000 grams.) But they soon discovered that the 54-megagram and 72-megagram-per-hectare rates were too unwieldy in volume to mix into the ground effectively.

U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center

U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Pulverized paper awaits incorporation and seeding for degraded training lands.

“When we applied too much of this material, it became almost impossible for us to incorporate it into the soil,” he says. “We couldn’t disk it in…. And so it just became a blanket of this white paper on the top of the [soil] surface.”

Torbert says he suspects that the paper overload may have been counterproductive and choked plants, preventing their growth and thereby affecting plant mass measurements. But the team only realized it was an issue after they had attempted to incorporate the compost into the blocks of infertile soil. To avoid the same issue in fertile plots, they proportionally reduced the amount of paper compost they added. Hence the divergent results.

Given the technical limitations at military facilities—most don’t have the equipment to disk heavy amounts of compost into soil—the researchers recommended DOD mix paper compost into soil at a rate of 35 megagrams per hectare—or about 39 U.S. tons per hectare. Compared with average paper disposal and soil restoration costs on U.S. military facilities, diverting shredded documents to compost would save DOD $2,000 per acre, researchers calculated.

Healthier soil, less waste, and taxpayer savings make this idea seem like a real win-win-win. So at this point you’re probably wondering: Is there a catch? Well, yes.

Compost made from shredded documents can contain heavy metals and bisphenol A (commonly known as BPA), due to certain kinds of printer ink or compact discs that are accidentally processed along with the paper. In high quantities, these substances can pose risks to wildlife. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains regulations on heavy metal concentration in landfill waste, as well as cumulative limits for a given area of land.

Researchers analyzed shredded DOD document samples and found that, with the exception of zinc and copper, concentration of metals that they tested for fell below detection limits. Zinc levels were present at the highest concentration, at 20 parts per million—still far below EPA’s threshold of 7,500 parts per million. BPA levels clocked in at 483 parts per billion, a value at which potential harm is harder to qualify because EPA has not established environmental BPA limits.

Though this study was specific to soil needs in military facilities, it hints at possibilities for broader agricultural applications. Researchers cautioned that shredded paper, with its high carbon content, wouldn’t necessarily make for good compost in growing crops, which rely on nitrogen-rich fertilizer. However, they noted, shredded paper could be a cost-efficient tool to restore soil that has been damaged by industrial agriculture.

“For conservation practices, this would be really useful,” says Ryan Busby, a U.S. Army researcher involved in the study. He highlighted a USDA land conservation program, which financially incentivizes farmers to take damaged farmland out of production. “Where you take certain areas of land out of production and [apply] conservation practices, increasing soil carbon and increasing soil health is really important.”

The method could also facilitate growth of grasses on pasture-based livestock operations.

“If you had some areas that had been, say, overgrazed, so you had deteriorated the soil, this would be a way to reestablish that land, so that it would be more productive,” Torbert says.

The study’s findings were published in science journal Soil & Tillage Research in August, and its recommendations were finalized in a user guide distributed through DOD in September, giving military facilities across the country the parameters to start composting documents at any time. For my part, I’ll just keep hauling my food scraps to the Sunday farmers’ markets.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the title of the science journal in which these findings were initially published. The journal is Soil & Tillage Research, not Elsevier.