Graphic by Alex Hinton/Annie Wells Getty Images/Tina Vasquez/Gary Soto

Gary Soto had no idea his children’s book would become a classic. Twenty-three years later, it still plays a vital role for countless Latino families.

I was in elementary school the first time I heard The Joke.

“Why do Mexicans eat tamales for Christmas? … So they have something to unwrap.”

I was a third grader at Alameda Elementary School in Downey, California, sitting in the school library minding my own business, when a shaggy-haired blonde kid whose name I don’t recall approached my table. Flanked by giggling friends, he could barely get the words out of his mouth before erupting in laughter.

I sat there staring blankly, not understanding the punchline. I mean, we do eat tamales for Christmas. What was funny about that?

“That kid’s a dick,” my older brother Manny explained to me after school. “He was making fun of Mexicans for being poor.”

I had the very particular experience of growing up in a city just as it was becoming majority Latino. As historian Aron Ramirez explained in a seven-part series for the newspaper Downey Patriot, the “Mexican American suburbanization” that occurred in Downey was not unique in Southeast Los Angeles, but how and when Downey transformed from a white middle-class suburb to “Mexican Beverly Hills” in the ’90s made the city an anomaly. Downey’s shift coincided with national racial tensions tied to the police beating of Rodney King and the subsequent uprising known as the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Around the same time, anti-immigrant animus ran rampant in California, illustrated by the 1994 ballot measure Proposition 187, which aimed to bar undocumented immigrants like my family members from accessing public education and other services.

The pride in my culture and heritage that my dad tried to channel into me at home mostly evaporated out in the world.

In context, I suppose it’s not so surprising that during this time I first began to hear words like “beaner,” “migra,” and “wetback.” That last one—a slur my dad got relatively frequently—is a reference to migrants who cross from Mexico into Texas across the Rio Grande. My dad walked across the border into California—I guess it makes sense that racists are intellectually lazy.

I grew up in a complicated environment with a white American mom and a Mexican immigrant father in a mixed-status, bicultural home. My parents looked like polar opposites of each other, leaving me with unease and uncertainty about my place in the world. The pride in my culture and heritage that my dad tried to channel into me at home mostly evaporated out in the world. Even something as loving as a home-cooked meal became a minefield. It wasn’t just the crack about tamales. For lunch, my dad sometimes sent me to school with leftovers packed in repurposed margarine containers. One time, the kid next to me at the cafeteria table held her nose and complained about the smell of my chorizo and potatoes.

Heartbreak is prominent in many of my childhood memories related to identity. That said, every December I remember a small, sweet childhood moment in the Downey City Library that changed the way I saw myself. My favorite part of the old library was its entrance, where seasonal children’s books were displayed on a wall.

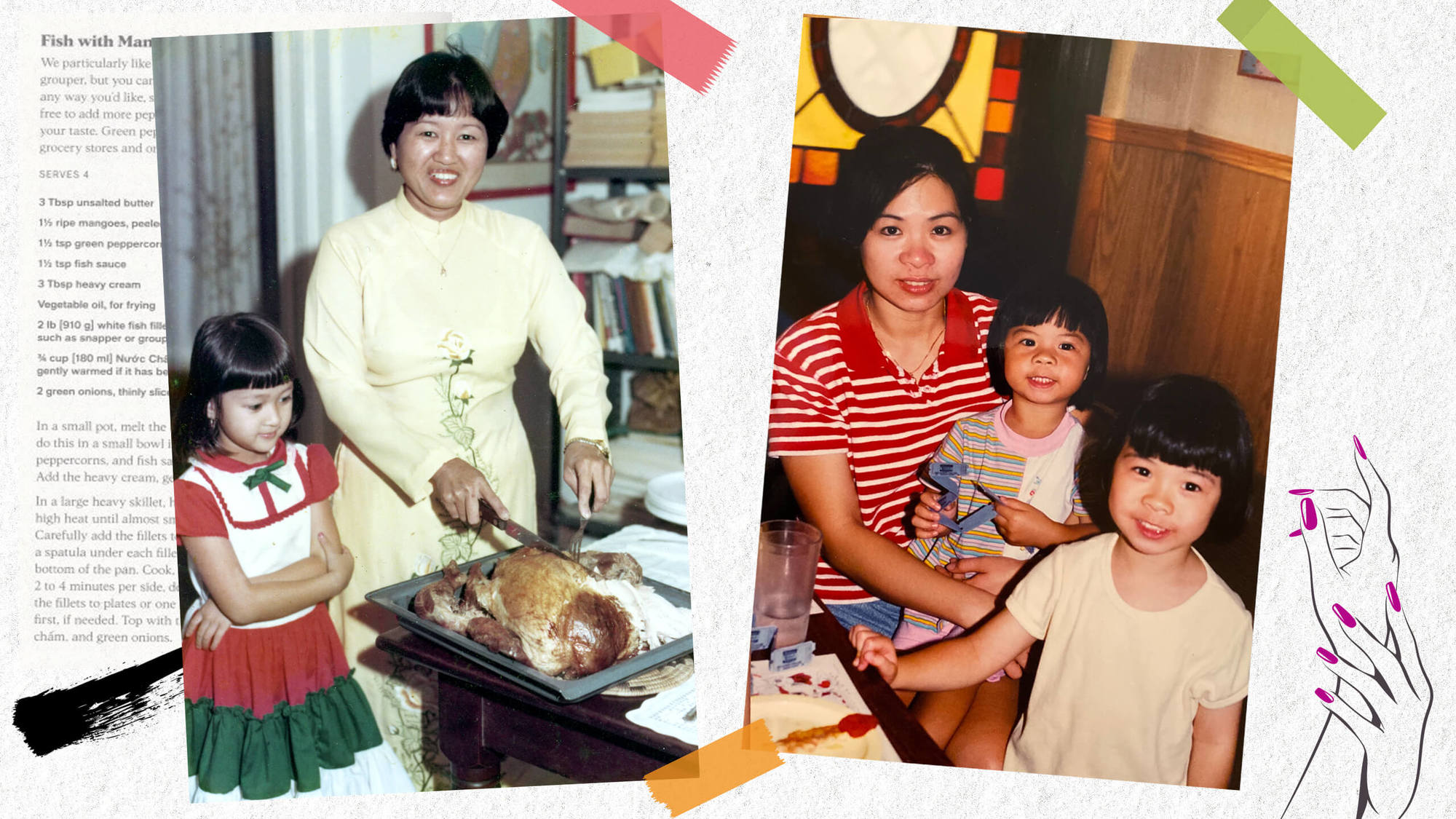

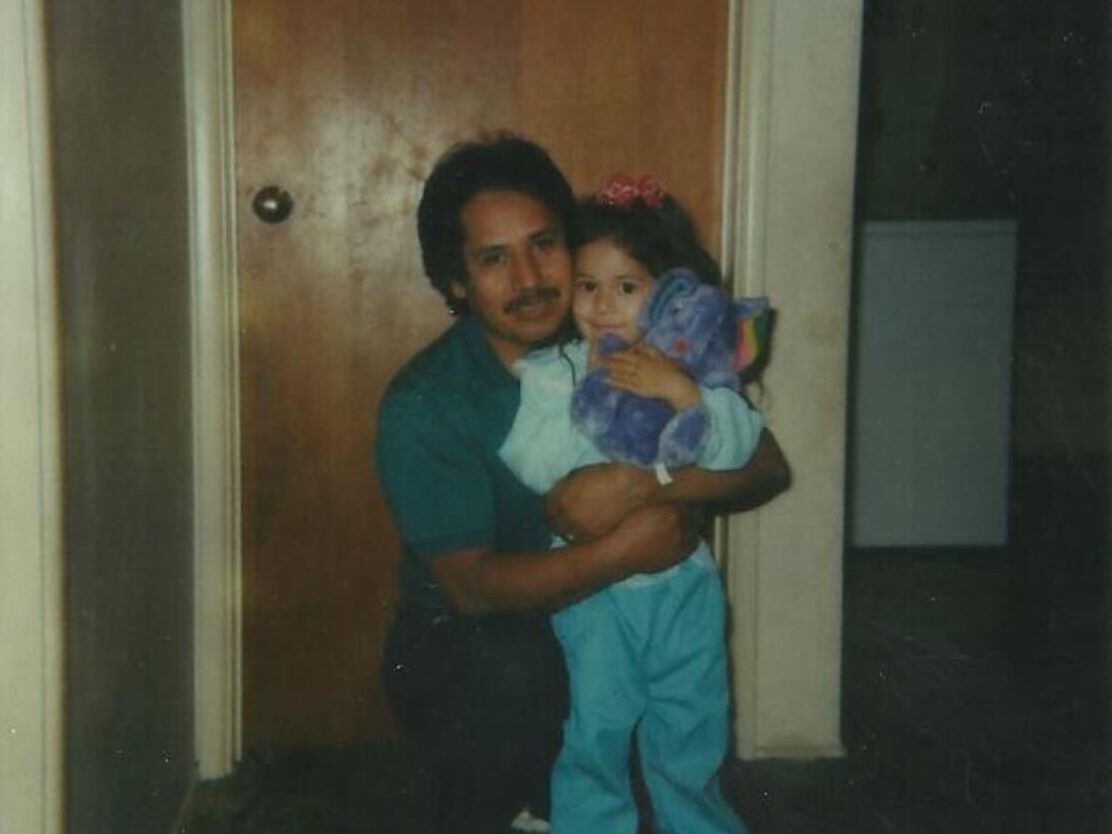

A childhood photo of senior staff writer Tina Vasquez with her father in 1988. For Vasquez, Too Many Tamales was the first time she saw a familiar tradition represented in a book with characters who looked like her.

Courtesy of Tina Vasquez

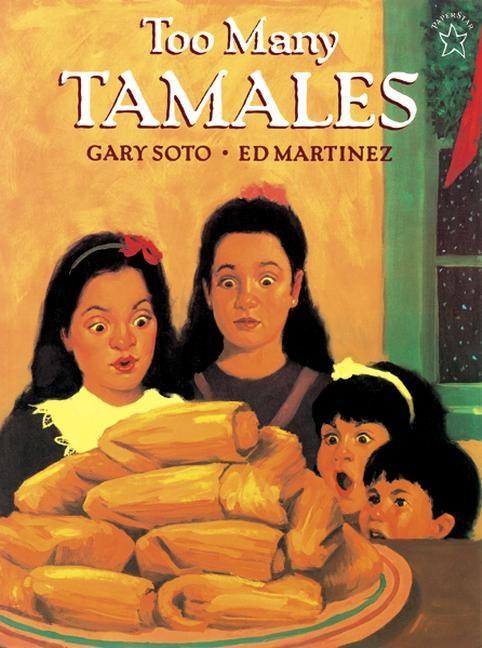

This is how I first laid eyes on Too Many Tamales, a now-classic children’s book published in 1993 by author, poet, playwright, and all-around Chicano literary hero, Gary Soto. I can still remember first seeing Ed Martinez’s cover art–with its warm hues and brown, dark-haired children staring at a pyramid of tamales piled atop a platter, a Christmas wreath barely visible in the corner.

I grabbed the book and took it to my favorite desk at the back of the children’s section to devour. There was no heavy-handed message about identity, no overt reference to the Mexican American tradition of Christmas tamal-making. It’s a straightforward story about a little girl who thinks she lost her mother’s ring in some masa that was used to make tamales, so she and her cousins try to eat their way out of trouble.

Yet the book was the first time I saw a familiar tradition presented as a simple matter of fact, told through the eyes of children who looked like me, written and illustrated by men with the same kind of last names as other people in my community: Soto and Martinez.

“We were also surrounded by almonds, plums, grapes, and cotton. It went on for miles and miles. It was all inescapable, so I wrote about it.”

—Gary Soto

My Counter colleague Patricia I. Escárcega once said that writing about food is a sneaky way of talking about everything because food is an easy shorthand for understanding cultural identity. In a recent phone interview from his home in Berkeley, California, Soto, 69, told me that food and agriculture were the focus of his early writing because it’s what he knew. In a piece he shared with me about his “personal and political affinities,” he wrote that one of his earliest memories is “mindlessly eating grapes” from a vine that he sat under while his mother picked fruit with a Filipino family. The kind of work he saw his family do is the kind of work he thought he would do too, especially when he left high school with a 1.6 GPA. But attending Fresno Community College changed the course of his life; he discovered literature and began writing poetry.

Courtesy of Puffin Books | Illustrated by Ed Martinez

“It felt lovely to just write, but there was no evidence in my family that I could do this for a living. In my family, we were either janitors, farmworkers, or we worked in some kind of factory,” Soto said. “Our family worked at Sun Maid Raisin factory, which was only a block and a half away from where I lived. So the sound of machinery and the smell of grapes were permanent fixtures in our community. As a matter of fact, I could look out my window and I would see the factory where my grandmother worked, where my uncle worked, where my grandfather worked. Not too far away, my mom worked at a potato peeling factory called Redi Spuds. We were also surrounded by almonds, plums, grapes, and cotton. It went on for miles and miles. It was all inescapable, so I wrote about it.”

Soto is now established as one of the San Joaquin Valley’s fiercest champions, and one of Fresno’s most beloved sons. At 23, he published his first book of poetry, The Elements of San Joaquin, suffused with his love of the region and respect for agriculture. He told me that farming doesn’t really play into his literary life anymore, but food has remained a near constant theme. As we spoke on the phone, he leafed through one of his poetry books–oranges, raspados, tortillas, chicharrones, and pomegranates all made an appearance in one volume. Currently, he’s producing a feature-length film based on his Fresno-based novel, Buried Onions.

When Too Many Tamales was published in 1993, Soto said he had no idea that it would turn into a “quasi-classic” or that it would be such a phenomenon in both reach and acclaim. The children’s book was published three years after his first book for young readers called Baseball in April, a group of short stories based on Soto’s experience of growing up low-income in Fresno.

“I think after that, the publishing world had to start thinking about Mexican Americans. That’s how Too Many Tamales came to be, and it too just hit home. It spoke to a lot of people.”

—Gary Soto

“I had a hard time convincing publishers about Baseball in April. They basically said, ‘Who wants to read about Mexicans?’” Soto said. “But it became an instant bestseller; it just flew off the shelves. I think after that, the publishing world had to start thinking about Mexican Americans. That’s how Too Many Tamales came to be, and it too just hit home. It spoke to a lot of people.”

A Christmas book about eating too many tamales was bound to be an enduring classic, one that would continue to have a nostalgic stronghold on Latino communities today. The book is still read each year by countless children across the United States. When Latinx writer Wendy Ortiz became pregnant, a family friend gave her two copies of Too Many Tamales, one in English and the Spanish version published in 1996.

“I knew [the book] would stay in our family as a story reflective of an aspect of our culture,” Ortiz told me.

Too Many Tamales is also now a play, and it will become a musical next year, produced by two young women who licensed the story from Soto. City officials even recently told Soto that there’s going to be a Too Many Tamales-themed area of a Fresno park. The author remains pleasantly surprised by its popularity.

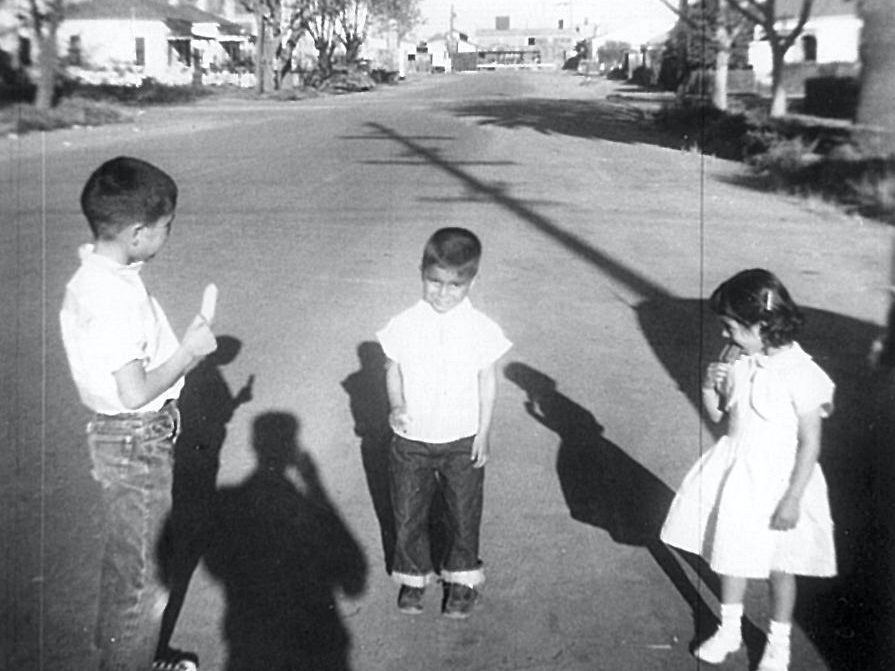

A childhood photo of Chicano literary hero, Gary Soto (center), with his brother and sister.

Courtesy of Gary Soto

“It’s kind of weird because I think of myself as a poet and that is what I want my legacy to be,” Soto said. “But I also can’t complain. I’m a basic poet, and poets hardly get any attention at all.”

The irony is that Soto’s family didn’t partake in Tamal Season–at least not in the traditional sense. His family didn’t gather together for a tamalada, a party where everyone participates in the arduous task of making dozens of tamales around Christmastime. Instead, his family bought them from a small store in Chinatown. I can relate: My family didn’t participate in tamal-making either. At Thanksgiving, my dad purchased two giant turkeys and one remained in the freezer until Christmas so that my parents could make enmoladas for the neighborhood. We depended on family members to bring us homemade tamales for Christmas, and my grandfather’s Salvadoran neighbors always shared a batch of theirs, wrapped in banana leaves.

I didn’t learn to make tamales until I was an adult. My friend Gabbie’s mother, Maria Socorro Ibarra, stayed up all night on Christmas Eve to teach me, painstakingly making dozens of tender tamales with the perfect filling-to-masa-ratio. This will be Gabbie’s first Christmas without her mother; I will remain forever grateful that Socorro imbued us with ancestral cooking knowledge.

“I’ve embraced making [tamales] as an adult because it’s a community activity, and it’s a connection to my culture that wasn’t even taught in my family, that I can give to my kid.”

—Wendy Ortiz

Ortiz told me that she also learned how to make tamales as an adult. Growing up, her family avoided making them at home due to the time and effort it requires. Instead, her mom bought tamales each year from La Mascota, a Boyle Heights bakery serving Los Angeles for almost 70 years. But beginning in 2009–just before Ortiz gave birth to her child–she and her partner organized a tamalada, a tradition they’ve maintained over the years. It’s a marker of their family’s cultural identity, one that they want their child to embrace. But how their tamalada came to be seriously skirts tradition. The tamal-making party came about because Ortiz’s Korean-American partner used to make tamales with her Mexican ex’s family and it was a tradition she wanted to carry on with Ortiz.

“The first year I did it with my partner was in 2009, with about three or four friends. We started it up again in 2011 and invited more and more people every year until our last one in 2019–a total rager with at least 50 people coming in and out,” Ortiz said. “I’ve embraced making [tamales] as an adult because it’s a community activity, and it’s a connection to my culture that wasn’t even taught in my family, that I can give to my kid.”

Ortiz and her family are forgoing a big tamalada again this year because of Covid, but she’s made a few small batches of tamales with her partner and kid, including some stuffed with corn, green chiles, jalapeño, and Monterey Jack cheese. She doesn’t want the tradition to die, especially because she said there are many cultural traditions she had little to no exposure to because of her parents’ assimilation and estrangement from cultural practices.

“I want my kid to have a different experience than I did,” Ortiz said.

I understand how this kind of estrangement functions. I live in North Carolina now, a state with one of the fastest growing Latino populations in the country. But I too feel disconnected–from my community in Southeast Los Angeles and from the cultural practices that somehow feel more easily within reach when I’m home. I bought a home in North Carolina to plant deep roots in the state, but I still experience bouts of homesickness—including last month.

Soto made so many of us–especially working class Latinos– feel seen and heard for the first time.

My dad and my niece Dakotta came to visit me and during their visit, I had the opportunity to introduce her to Too Many Tamales. I told her the story of when I first came across the book and how it made me feel when I was a little kid, attending Alameda Elementary School like she is now. Afterwards, we sat around and talked about all of our favorite Mexican foods. It was one of those rare moments you sometimes have with kids when you feel like you’re making a memory they will remember fondly later.

When Dakotta and my dad returned home, I experienced that familiar sad and untethered feeling I always get when I miss my family. But I had anticipated brooding over their departure, so weeks before I placed an order for tamales with a new immigrant-owned catering business in my adopted city, Winston Salem. I thought tamales could soften the blow.

As I sat at my dining room table unwrapping my first tamal of the season, I thought about Gary Soto and Too Many Tamales. Soto was right: Poets don’t get much attention, but he deserves all the praise. He wrote about his home in a way that honored its history and its people, and he carved out a lane for himself when there were few prominent Mexican American writers in publishing. Soto made so many of us–especially working class Latinos– feel seen and heard for the first time.

As I tucked into one of the best rajas con queso tamales I’ve ever had, I realized that reading Too Many Tamales to my niece is its own kind of cultural tradition–one that honors who we are and that can represent our family’s trajectory from Mexico to Southeast Los Angeles and now North Carolina. Just like tamaladas, this little book allows us to travel across space and time together–and we don’t even have to prepare time-consuming fillings or figure out how to make moist masa.