Go fish. As our phones blow up with intermittent bits of #ComeyHearing coverage, and we all gasp for a wisp of obstruction-free air, my thoughts drift outward—in directions both east and west—to the more than 70 percent of our earthly surface that isn’t on Twitter today: the sea.

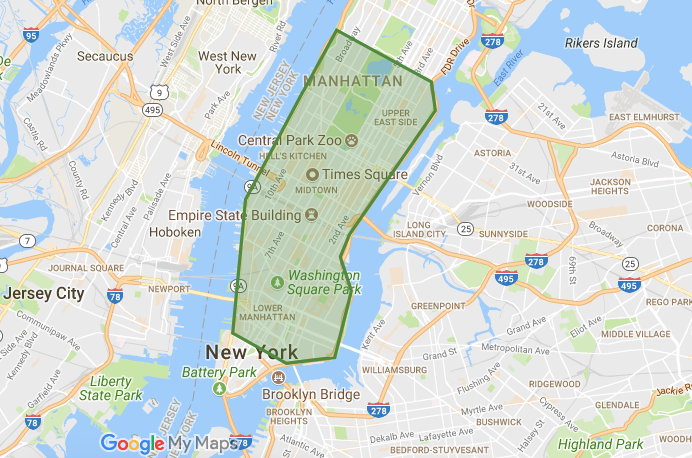

Turns out it’s a great day to ponder the wide, wet world beyond D.C. A great week, actually. And global leaders on both coasts are doing just that. The Ocean Conference and Seafood Summits—at the United Nations in New York, and in Seattle, respectively—have convened representatives from government, business, and nonprofit sectors worldwide, for a week of conference-y type words like, “targets,” “indicators,” and “progress.”

What that really means is they’re gonna gather, commit, pledge, and basically, ya know… figure out how to advance a sustainable future for our oceans, seas, and marine resources.

No big.

Let’s just widen the aperture for a moment. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, there are over 332,519,000 cubic miles of water on the planet. And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says that about 321,003,271 cubic miles of that volume is in the ocean. That means roughly 97 percent of the earth’s water is in the ocean.

Now, we’ve all been through a lot today so I’m not going to harp too long on the bottomless sea of marine-related concerns. But it’s worth knowing a couple of key things from this week’s larger, east coast convergence. In September of 2015, the UN developed its 2030 Agenda for Sustainability, a broad (and I do mean broad) plan of action that sought, among other things, to end poverty and hunger everywhere; to combat inequalities within and among countries; to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies; to protect human rights and promote gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls; and to ensure the lasting protection of the planet and its natural resources.

That final bit, about lasting protection of the planet, was the focus in New York this week. Of course, it wouldn’t be the UN without the formation of a commission, which makes an agreement of some kind, which leads to a practical starting point, and ends in a report. And the group responsible for the Ocean Conference report was the UN Statistical Commission. It laid out a framework that indicates several interesting (and again, broad) targets:

- Significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds by 2025

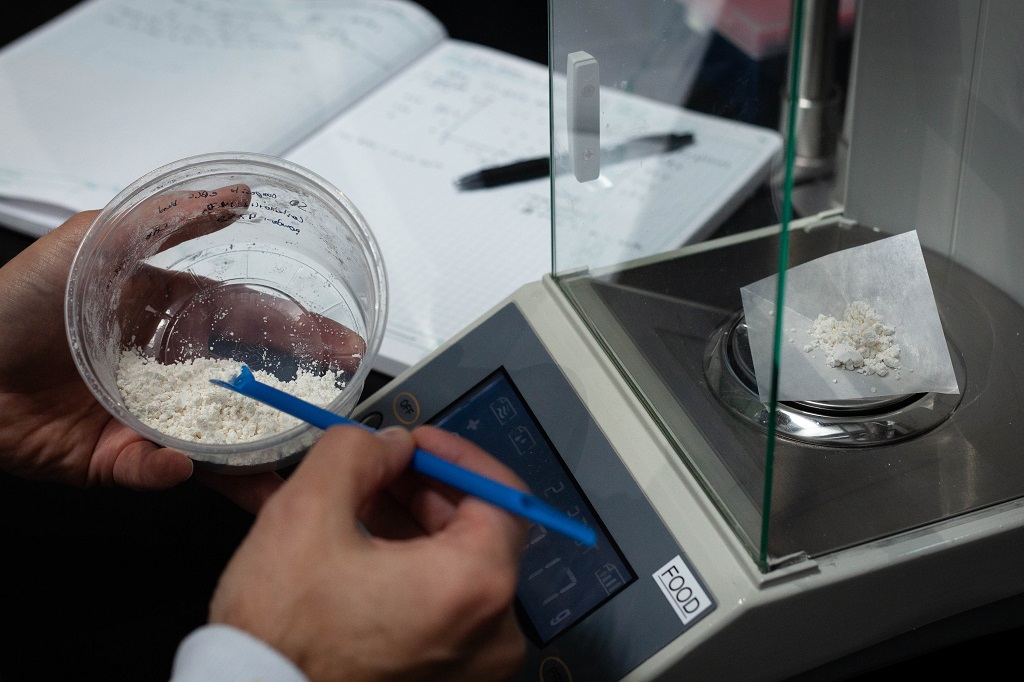

- By 2020, effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics

- Provide access for small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources and markets

We reported through much of last year about the crisis of declining fish stocks in the Atlantic, small-scale efforts to curb a bait shortage in Maine by replacing prey fish with synthetic and artificial bait, and cope with cod quotas by equipping commercial fishing boats with electronic jigging machines that target and catch specific, abundant species like pollock, and avoid catching protected species like cod.

And over on the fairer coast was the Pacific to Plate bill, a practical little piece of policy that allowed fishermen to organize like farmers’ markets so that they can more easily (and profitably) sell to the public.

The efforts, as I said, were small-scale. But they were specific. And in use. And working. And while I like the sweeping findings and lofty goals of high-level political forums as much as the next gal, after reading into what the UN conference aimed to achieve— “adopt by consensus a concise, focused, intergovernmentally agreed declaration in the form of a ‘Call for Action’ to support the implementation of Goal 14 and a report containing the co-chairs’ summaries of the partnership dialogues, as well as a list of voluntary commitments for the implementation of Goal 14, to be announced at the Conference” — I found myself longing for some crisp specificity.

Voluntary commitments—to date, 1001 and counting—from NGO, government, civil, philanthropic, academic, and other entities, to meet the 14 sustainable development targets laid out at the conference (three of which I listed above), are just that: voluntary. And we were reminded post-Paris-pullout last week just how flimsy and ephemeral a voluntary commitment can be.

As fires continue to burn at the federal level, we may do well to remind ourselves that much of the most effective food and environment policy is being made (and implemented, and enforced) by state lawmakers, and the sharpest innovation by scientists in smaller places. Global goals are good. But what if we sliced a little thinner?

“It’s pretty doable to start off at a smaller volume that sort of adds some value to my trip, makes some money for me over the course of the year,” said Adam Baukus, a research associate at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, in our story about the jigging machines in use in Maine. “And then … maybe I can build that part of my portfolio up a little bit so if things were to change, I could start focusing more on it.”

Dear, towering, and largely symbolic UN: think Baukus might be onto something there.