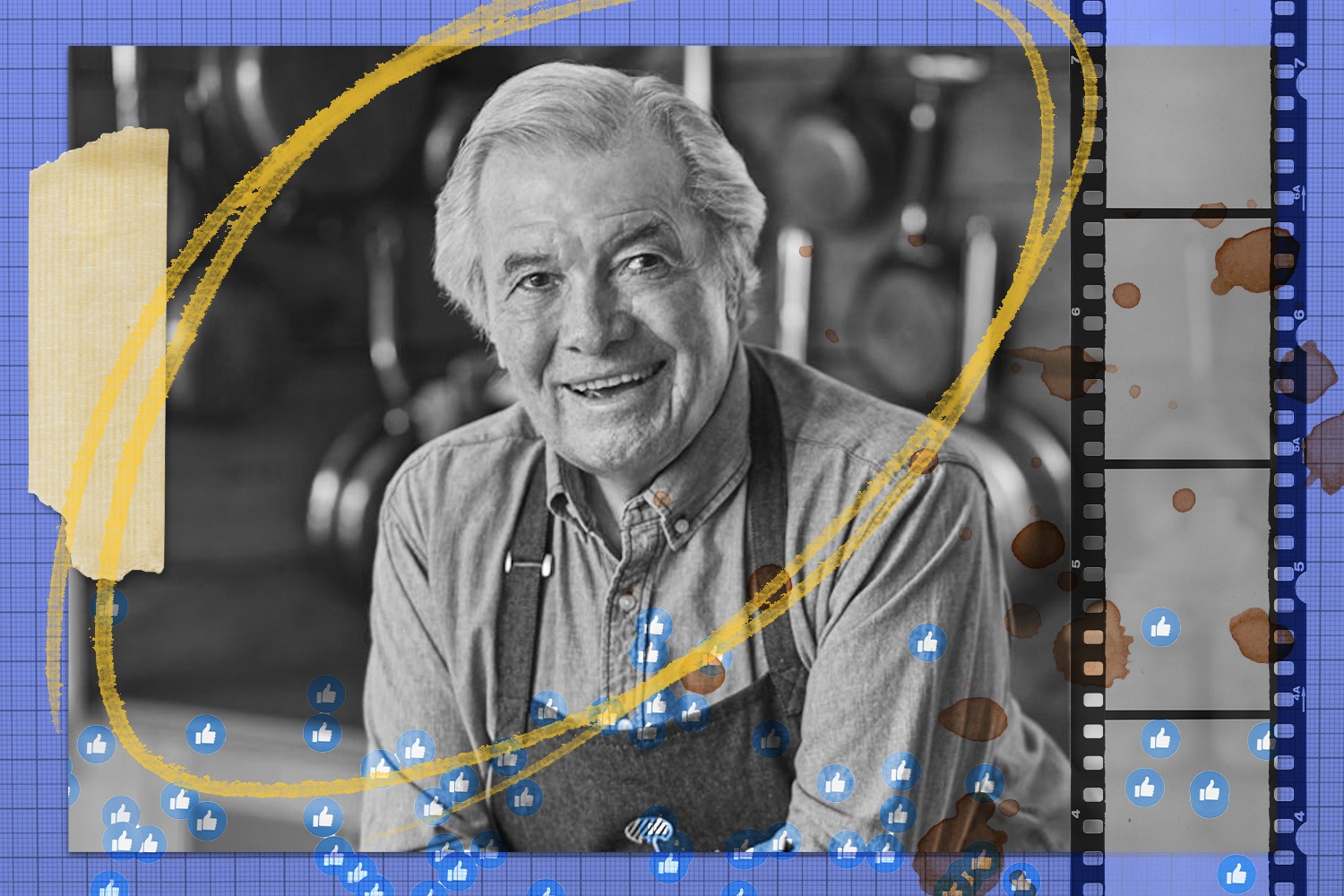

Portrait: Courtesy of the Jacques Pépin Foundation | Collage: Talia Moore for The Counter/iStock

Jacques shared his knife skills with viewers stuck at home, kept his foundation afloat when funding dried up, and helped prepare formerly incarcerated job-seekers for food-service work.

It takes un village to be Jacques Pépin, these days: The 85-year-old chef and educator’s expanding identity roster now includes Facebook celebrity, activist, and, according to GQ, online style icon. When the pandemic sent all of us home, his first instinct was to help us cook, with a batch of instructional videos posted on social media. Next he turned his attention to The Jacques Pépin Foundation, which teaches job skills to formerly incarcerated people but had canceled three fundraising events; it needed help as well. Along with his daughter, Claudine, the foundation’s president, and Rollie Wesen, its executive director, Pépin created a video recipe book full of recipes contributed by a network of chefs, which went to everyone who bought a $40 annual membership. Wesen joined Pépin for this conversation, to talk about what came next.

—

Jacques Pépin: My daughter, Claudine, had this idea, because everyone was at home. I really don’t do Facebook but she has for years. And she said, ‘People are at home, they’re interested in cooking, can you do something using the stuff in your fridge, in your freezer, something that’s not complicated?’ I’m always using stuff that’s left over, what my wife used to call ‘fridge soup.’ Maybe because I was raised during the war in France, I’m pretty miserly in the kitchen. My father would never throw out a piece of bread without kissing it first and giving it to the chickens. So I said, ‘Fine, this is what I do normally, no problem,’ and we decided to do an online cooking series for Facebook and Instagram, for everyone to have, for free. It’s been easy, and, frankly, rewarding in many ways.

People were stuck at home, looking for something to watch, and it was easy enough to follow what I was doing, an hour of basic technique, with Claudine in the kitchen with me: how to use your knife, how to cut vegetables, how to use what you have and not waste it.

The process of cooking, of doing the techniques, is repeat, repeat, repeat. I’ve been in the kitchen 72 years—I left home in 1949—so I can go on TV and talk to people while I’m working with the knife. I don’t think about my hands anymore. But you can teach people that; anyone can acquire the technique. Some people do it much better than others, but it’s a question of practice and repeat.

Cooking, especially in a year of the pandemic and polarization of the political system—food is the great equalizer. When you sit down, there are no enemies. There is no color of skin in the eye of the stove.

Rollie Wesen: I think Jacques was the perfect balm for people during the pandemic. And all the recipes were geared to two to four people, which helped. Most cookbook recipes are for four to six people, but suddenly everybody was cooking at home for themselves. And Jacques has this soothing, calming persona. I think that contributed to the popularity.

JP (laughing): We used to have about 300,000 followers on Facebook. Now we have 1.4 million.

It was a double-edged sword, the pandemic. Some people got divorced, couldn’t stand each other, but other people got closer—and food brought them together. People realize how important it is to sit down together, more than ever before. They didn’t think it was so important before, but now they see, you can spend time at the table, share food and wine. Some people still don’t realize this; it’s their loss.

RW: There was also a moment in the fall of 2020 when we realized, through our community kitchen partners, that food insecurity was going up dramatically, from 45 million people to 55 million last year. Our community partners told us; lots of people are getting handouts for the first time in their lives, and they don’t always know what to do with what’s available to them. So we added a budget cooking series, about 20 true budget recipes, canned and frozen products, and said, ‘Here, Jacques, do some recipes with these.’

The point was to destigmatize the products. People were embarrassed, looking at a bag or box of food and wondering what the heck they’d do with it. So we did a broiled Spam steak with lima beans. How different is Spam from a good terrine?’

Jacques, left, his daughter Claudine, right, and Rollie Wesen, above, created a video recipe book full of recipes contributed by a network of chefs, which went to everyone who bought a $40 annual membership.

Ken Goodman

JP: What I wanted to show, also, was how to use the supermarket. It’s a revelation. In a restaurant you have people to do all the prep, but at home you don’t have that. So use the market for your prep if you don’t have time to do it yourself: pre-sliced mushrooms, boneless chicken, prewashed spinach, in five minutes you can have a meal.

RW: A lot of this wasn’t too different from what Jacques did before—it’s just more relevant. But there was one more challenge: The foundation, like other nonprofits, also had a very, very difficult year, with sources of revenues drying up just as demand was growing through the roof.

We have a barriers-to-employment program. We identified about 150 community kitchens when we started the foundation, but now Jacques is building a curriculum based on techniques, supported by videos, to help people find work. Our primary focus is formerly incarcerated people. Jacques said, ‘That’s what I want to do, they deserve another chance.’ But to continue to develop a curriculum we needed to raise funds.

Jacques was the perfect balm for people during the pandemic. And all the recipes were geared to two to four people, which helped. Most cookbook recipes are for four to six people, but suddenly everybody was cooking at home for themselves.

—Rollie Wesen, executive director of The Jacques Pépin Foundation

When Jacques started shooting his Facebook and Instagram videos during the pandemic, we saw the generous public response, and we saw that other chefs, friends, were making videos. We were trying to continue to generate revenue for the foundation—we’d only done in-person events before—so we reached out to them and said, ‘Would you do a video to raise money?’ In that first group, everyone said yes. You can hardly name a chef who didn’t produce a video for us.

That was the birth of the video recipe book. We took that content and asked ourselves, how can we use this to generate revenue? And we decided: If you join the foundation, and a membership is $40 a year, quite affordable, you get access to the video recipe book.

And now, we are working with the online culinary curriculum provider Rouxbe to create a culinary training curriculum using Jacques Pépin techniques. The 30-hour course will be available by the end of the year.

JP: I’m doing 10 videos tomorrow; in all we will have close to 200 in the “Jacques Pépin Cooking at Home” series, most on the Facebook page, some on the foundation website. Maybe I do a little less than I used to—I have someone helping with the garden now, it’s too much work—but my life is basically the same. I cook one way or another every day. I have done over 30 cookbooks, 26 shows, hundreds for KQED in San Francisco and WGBH in Boston, for years and years. These new programs have been easy for me, and frankly, rewarding in so many ways. I make simpler things in a simpler way, now—as you get older your metabolism changes and you want something simpler, without embellishment. And you always want to have fun in the kitchen. It’s possible to do something lovely that’s great fun.