iStock/FatCamera

It could be weeks or months until the second stage of Covid-19 vaccines go to essential workers. Right now, it’s unclear who will be included.

With the initial rollout of the Pfizer vaccine currently in Phase 1a, agriculture and meatpacking are just two of the sectors employing “critical infrastructure” workers who have turned their sights to their role in CDC’s Phase 1b–the stage of vaccine rollout when essential workers, including those at every level of America’s food supply, will become eligible for the vaccine.

The Pfizer vaccine, green-lit for emergency use by the FDA on Dec. 11, will first go toward treating two groups the CDC has deemed vital for containing the COVID-19 pandemic: frontline health workers and those living and working in nursing homes. Depending on supply and distribution for those in Phase 1a, the vaccination of the nation’s essential workers could be several weeks to months away. The Moderna vaccine, green-lit on December 18, will go towards the same efforts.

A key question for many: Will farm and food workers be included in the essential worker vaccine rollouts?

In the days leading up to the Pfizer vaccine approval, the food industry and labor advocates alike doubled down on efforts to ensure food workers are prioritized.

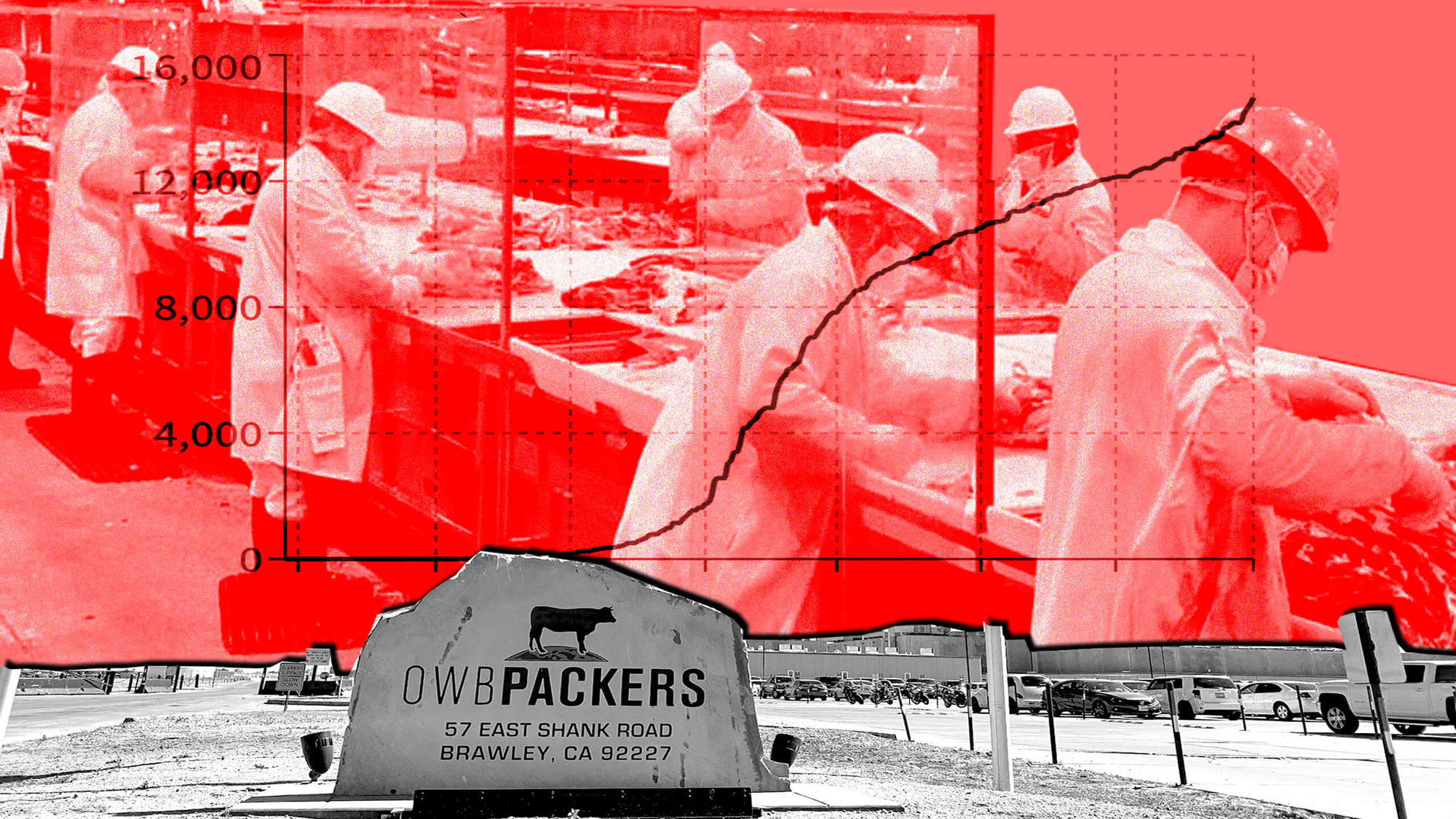

In the early pandemic, shelter-at-home orders and lockdowns sent the food supply into a tailspin, causing food shortages at grocery stores and a multitude of COVID-19 cases and deaths linked to farm workers and meatpacking facilities across America. Via an April executive order, President Trump kept meat and poultry facilities operating despite outbreaks, deeming them a critical infrastructure industry. Since then, several major meat producers have been fined for Covid-19 outbreaks, including Smithfield and JBS.

Among agricultural workers, case rates are harder to track, with significant underreporting from workers unaware of testing sites or unwilling to get tested for fear of loss of income. A UC Berkeley study published Dec. 2 with over 1,000 California farmworkers found that 13 percent of the workers in the study tested positive for COVID-19, compared to the 3 percent positive rate for the state’s general population. Nationwide, FERN previously reported over 72,000 workers in the food system had tested positive for COVID-19 as of Nov. 13–including meatpacking, food processing, and farm workers.

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

In the days leading up to the Pfizer vaccine approval, the food industry and labor advocates alike doubled down on efforts to ensure food workers are prioritized in state-level vaccination decisions. In November, 11 California-based farmworker workers’ rights groups released a letter advocating for the state’s produce pickers and meatpackers to be prioritized in vaccine distribution, per The Desert Sun.

“What we’ve seen now is that infection rates among workers in the food chain supply have been significantly high and disproportionate to other industries.”

Last month, 15 nationwide trade groups from every level of the food supply chain also sent a similar letter addressed to President Trump. The Meat Institute, one of the signatories, then sent a follow up letter to the CDC committee responsible for vaccine distribution guidelines, urging the priority vaccination of USDA inspectors and meat and poultry workers.

Thus far, few lawmakers have thrown their support behind prioritizing workers in the hard-hit agricultural and meatpacking industries. In California, several farmworker labor groups are part of the state public health department’s community vaccine advisory committee, which will help guide California decide how to allocate and distribute vaccines. State Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia, himself the son of farm workers, co-sponsored a bill on Dec. 4 that would signal the state legislature’s intent to prioritize workers in food supply for both testing and vaccine programs.

“What we’ve seen now is that infection rates among workers in the food chain supply have been significantly high and disproportionate to other industries,” Garcia said. “Of course we’re not trying to say folks should cut in the front of the line. We’re saying there should be a strategic approach.”

The CDC’s vaccination plan, released Dec. 1 and then updated on Dec. 21, serves only as a guideline for state and local governments to distribute the initially limited doses of the vaccine. When vaccination of those in Phase 1a is complete, states and local health authorities will begin giving doses to those in Phase 1b, which includes essential workers and people over the age of 74. The patchwork decision process means that trade associations and labor groups alike are lobbying across the industries and occupations employing the nation’s estimated 55 to 74 million essential workers–all in hopes of gaining priority access to the vaccine, The Wall Street Journal reports.

“If you can be strategic in how you disseminate it, you might be able to cover a bunch of the folks and not pick winners and losers.”

At day’s end, state and local health departments will have the ultimate say in which essential workers get the vaccine first, a decision that is beginning to be made over the holiday season.

In Kansas, Democratic Governor Laura Kelly said in early December that the state’s meatpacking employees would be near the top of the essential worker priority list, but qualified her comments, saying plans were subject to change. The state’s meatpacking facilities have been home of the state’s largest outbreaks, with two plants responsible for over 500 cases each as of September, according to The Kansas City Star.

As the nation faces rising case numbers, overburdened ICUs, and a vaccine rollout limited by cold-storage facilities, the meat and agricultural industries are hoping decision-makers will remember the sacrifices made by food workers. Many food and farm workers will have no choice but to work in unsafe conditions as the virus continues to spread. Feeding the nation has never been more dangerous, yet thus far state and local officials have been unwilling to protect those who make dinner on the table possible for millions of Americans.

“If you can be strategic in how you disseminate it, again, you might be able to cover a bunch of the folks and not pick winners and losers,” said Garcia, who still has family members working in the fields. “And not be like, ‘Well, why them before them?’”