Testing by a pair of environmental nonprofits found that several forms of packaging at McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s had been treated with chemicals that increasingly concern public health experts.

Update, August 7, 2020 at 3:01 PM EST: This story was updated to include comment from Footprint that came in after publication.

It’s been one year since an investigation from The Counter revealed that molded fiber bowls—the “compostable,” seemingly earth-friendly containers popular at fast-casual restaurants—contain PFAS, a class of potentially toxic “forever chemicals.” But a new report published Thursday by the anti-pollution nonprofits Mind the Store and Toxic-Free Future suggests even more widespread PFAS use in fast-food industry packaging, with significant levels turning up in a range of items from Big Mac boxes to fry bags.

PFAS, which stands for per- and polyfluorylalkyl substances, might be a confusing, cryptic -sounding acronym, but the term has become increasingly familiar to the American public as environmental advocates, federal legislators, and even Hollywood movie producers start to sound the alarm about their potential dangers. As I explained at greater length in The Counter’s investigation, the term refers to a broad class of fluorinated chemicals with a range of industrial uses, from waterproof apparel to firefighting foam and period-proof underwear.

Due to their tightly bound molecular structure, PFAS compounds tend to be excellent water and grease resisters—which makes them especially appealing to producers of food packaging. But these potentially toxic compounds come with one significant drawback: Many don’t break down naturally in the environment, even over the course of hundreds of years.

That’s a problem, because numerous individual PFAS compounds have been linked to a range of serious health effects, from thyroid disruption to cancer.

While it’s not news that PFAS is widespread in the take-out food business, the new report is apparently the first to look at a broader range of specific fast food burger chains.

Numerous individual PFAS compounds have been linked to a range of serious health effects, from thyroid disruption to cancer.

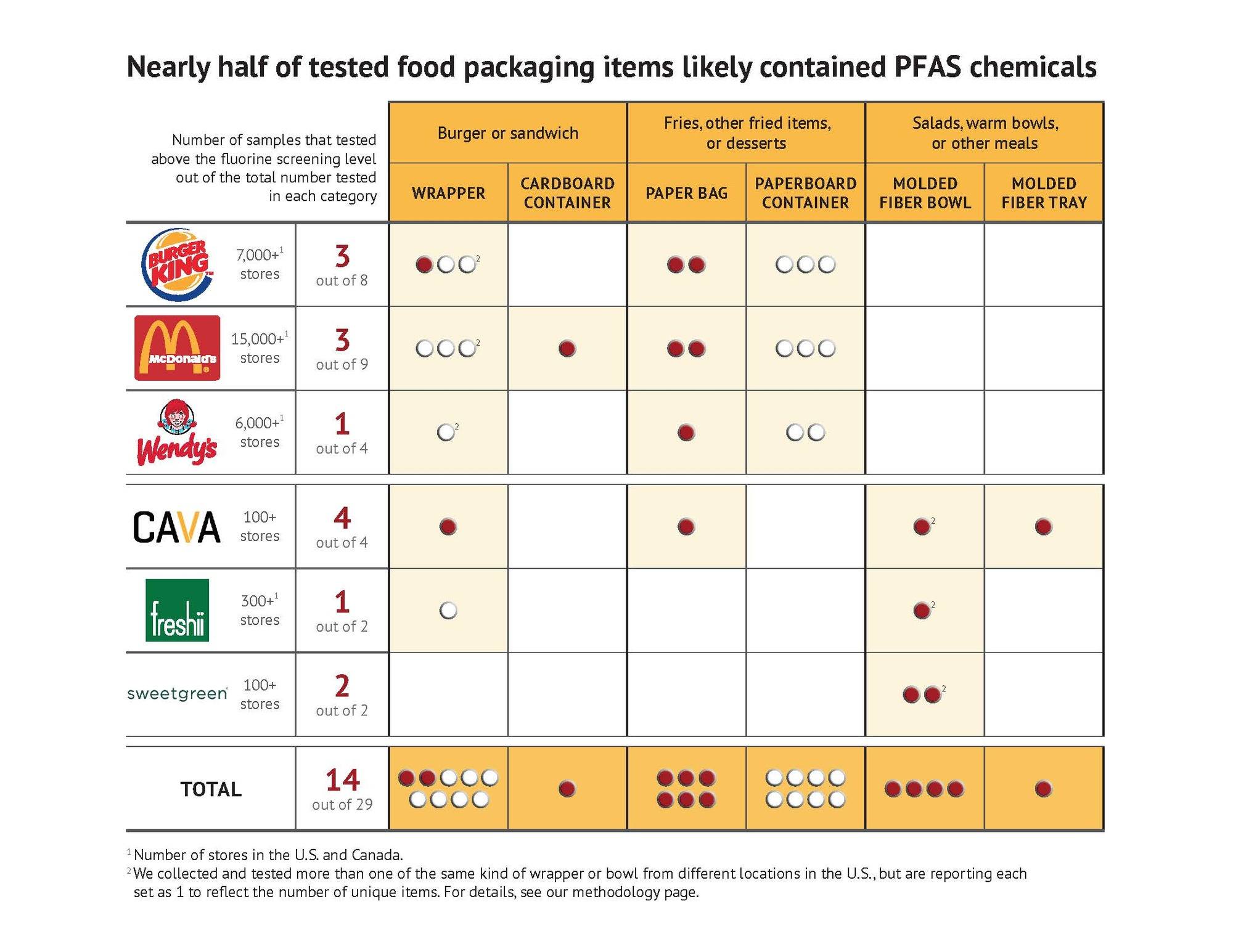

For their investigation, the groups gathered 38 varied food packaging samples from six fast-food chains, obtaining them from 16 locations across 3 regions—New York State, Washington State, and the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. What they found? About half of the samples contained PFAS above the 100 parts per million (ppm) total fluorine threshold recently adopted by the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI), a leading certifier of compostable products. Any reading above 100 ppm is a sure sign a product has been intentionally treated with PFAS.

But the interesting thing isn’t how many products tested positive—it’s what kind.

Unsurprisingly, all the molded fiber products tested—from the fast-casual chains Sweetgreen, Freshii, and Cava—contained PFAS. As I reported earlier this year, increased regulatory scrutiny and ongoing media attention have jump-started a race to find a replacement for PFAS in molded fiber take-out packaging. (Without PFAS, your food hall bowl would just wilt in your lap after brief contact with heat, moisture, or grease.) Both Chipotle and Sweetgreen have pledged to run PFAS-free supply chains by the end of 2020, though so far only Sweetgreen has managed to debut a bowl without forever chemicals—and in just one market, San Francisco. It remains to be seen whether that goal will be feasible, though packaging companies have slowly begun to pilot and promote new alternatives.

“We originally introduced compostable containers to make a positive impact on the food ecosystem, however, given the concerns around PFAS, we started working with new and existing suppliers as well as an independent safety expert to find a more sustainable and compostable solution,” Sweetgreen told The Counter, in an emailed statement. “With a limited number of suppliers capable of manufacturing at our volume in addition to the complexities that the pandemic has placed on production, we are still actively working towards this timeline.”

Footprint—the Gilbert, Arizona-based company that supplies Sweetgreen with its limited number of PFAS-free bowls, and has also created PFAS-free fiber packaging for retail brands like Beyond Meat—explained why its approach has so far been promising, but complicated to bring to scale.

“We are currently delivering PFAS free technology nationwide from our three manufacturing facilities and have ability to scale in each location,” a Footprint press representative wrote, in part, in an emailed statement to The Counter. “The barrier for some companies is the time that it takes to customize products for unique customer requirements, such as shape, that will seamlessly integrate with the customer’s production lines — which is the most effective way to make a switch away from plastic — without sacrificing quality, cost or change the customer experience.”

The Mind the Store / Toxic-Free Future report also found PFAS in Cava’s molded fiber tray, and in the bags for its pita chips. A representative from Toxic-Free Future said that the company, in response to the findings, has pledged to go PFAS-free by mid-2021—a commitment the company confirmed to The Counter shortly after this piece was published.

Given the fact that food packaging is based on sprawling global supply and distribution chains, restaurants may not even know what’s in their packaging unless they conduct independent testing of their materials.

The report also found the likely presence of PFAS in packaging from Burger King, McDonald’s, and Wendy’s—though the results had much less uniformity than in the fiber bowls. At Burger King, the likely presence of PFAS was found in the paper wrapper for the chain’s Whopper burger, and a white paper bag used for serving chicken nuggets—but it was not found on wrappers for two other burgers, or on several paperboard clamshells.

Results of testing by the nonprofit groups Mind the Store and Toxic-Free Future. A red dot means a sample tested positive, while a white dot means a sample tested negative. Multiple “replicates” were taken from samples to make sure no individual results were an anomaly.

Mind the Store / Toxic-Free Future

Burger wrappers from McDonald’s came back negative for PFAS, but Big Mac boxes were found to be positive, as were bags for fries and apple pies. At Wendy’s, the only samples that tested positive were brown paper cookie bags. Burger wrappers and fry cartons did not contain PFAS. The wide-ranging results demonstrate the difficulty of eliminating fluorinated chemicals from restaurant supply chains: PFAS may be present in one manufacturer’s cartons but not in another, or in a brown sandwich wrapper but not a white one. Given the fact that food packaging is based on sprawling global supply and distribution chains, restaurants may not even know what’s in their packaging unless they maintain close relationships with suppliers that conduct independent testing of their materials.

As the potential dangers of PFAS become more visible to the public, compostability certifications like BPI’s—which mandates that products contain less than 100 ppm total fluorine, and are thus PFAS-free—are likely to play an even larger role.

“Many of these chemicals are not sufficiently assessed for their impacts on human health, while others are known hazardous substances.”

In March of this year, an international consortium of scientists specializing in the fields of developmental biology, endocrinology, epidemiology, toxicology, and environmental and public health, published a paper to express concern about “food contact chemicals” including PFAS—arguing that the long-term health affects of such chemicals are still scarcely understood. Though we do know this: they are piling up inside our bodies.

“The human population is exposed via food to chemicals migrating from food contact articles such as food packaging,” they wrote. “Many of these chemicals are not sufficiently assessed for their impacts on human health, while others are known hazardous substances. As a consequence, we see a need for revising how the safety of migrating chemicals is assessed, using current scientific understanding.”

They suggested that nations and corporations invest in developing waste-free, closed-loop systems, which can sidestep the problems associated with single-use disposables. In other words, when it comes to the environment and our health, the best solution may be an old-fashioned one: rolling up our sleeves and washing more dishes.