Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock

New data reveal a problem that aid packages can’t fix—too many restaurants, all competing for the same customers.

Numbers don’t lie, but they do sometimes struggle with follow-up questions.

In the ramp-up to the federal government’s omnibus aid package, released Wednesday without any more restaurant aid, advocacy groups lobbed numbers to show how tenuous life continues to be for the sector, in a last-ditch attempt to secure more help. Shuttered restaurants, dire predictions of more closures to come, lost revenues, lost jobs; none of it was enough to sway Congress.

The National Restaurant Association tried to stay above the fray, insisting that “the path is directionally correct” for 2022 despite a decline in sales compared to pre-pandemic numbers, with anticipated increases in both sales and employment.

Without viable businesses, there’s no one to target for higher pay.

The follow-up question: Who exactly gets to travel that directionally correct path? The NRA’s membership is top-heavy with national chains that drew headlines in 2020 for getting as much as $10 million, apiece, in first-wave aid. A year later, the Restaurant Revitalization fund led off with a 21-day exclusivity period for over 2,900 priority applicants across the country, restaurants owned by financially-strapped military veterans, women, or people of color—who saw their aid evaporate after white owners in Tennessee and Texas filed discrimination lawsuits. The Small Business Administration estimates that nearly 200,000 aid applicants never got a dollar. They might quarrel with the NRA’s assessment.

One Fair Wage (OFW), which lobbies for an end to the tipped minimum wage, introduced a new campaign for a $25 minimum wage by 2026, the United States’ 250th birthday, as the best way to lure workers back to the industry they’ve abandoned. Wages, not aid for owners, are OFW’s priority.

There’s a longstanding, contentious debate about how best to address the wage imbalance between front and back of house, and what to do about tipping, in which OFW has always held out for a higher minimum wage and the end of the tipped minimum, because it doesn’t reward service so much as it fills the gap between tipped and standard minimum wage.

But that raises a chicken-and-egg follow-up: If restaurant owners don’t get aid to keep the doors open, where will better-paid restaurant workers get a job? Without viable businesses, there’s no one to target for higher pay.

The Independent Restaurant Coalition (IRC) campaigned hard for $48 billion in next-wave aid, but executive director Erika Polmar liked to break it down to a more palatable ask: $283,000 each for restaurants that have been left out in the cold so far. That was the average first-round amount for aid recipients who brought in $1 million or less in annual revenues, like the neighborhood place you might be heading to for dinner tonight.

“In real life, to me, it trickles down to this: You can save a business for $283,000,” she said, before she found out it wouldn’t happen.

That’s the heartbreaker, because it dovetails with a sad hunch that’s nagged at me, of late: The pandemic may be the proximate cause of restaurants’ woes, but they were wobbly on their pins before anyone heard of Covid, and the challenges they faced back then haven’t gone away. More aid might keep more places on their feet, for a while, but it isn’t a panacea for tough competition, which turns out to have survived even the shutdowns of the last two years.

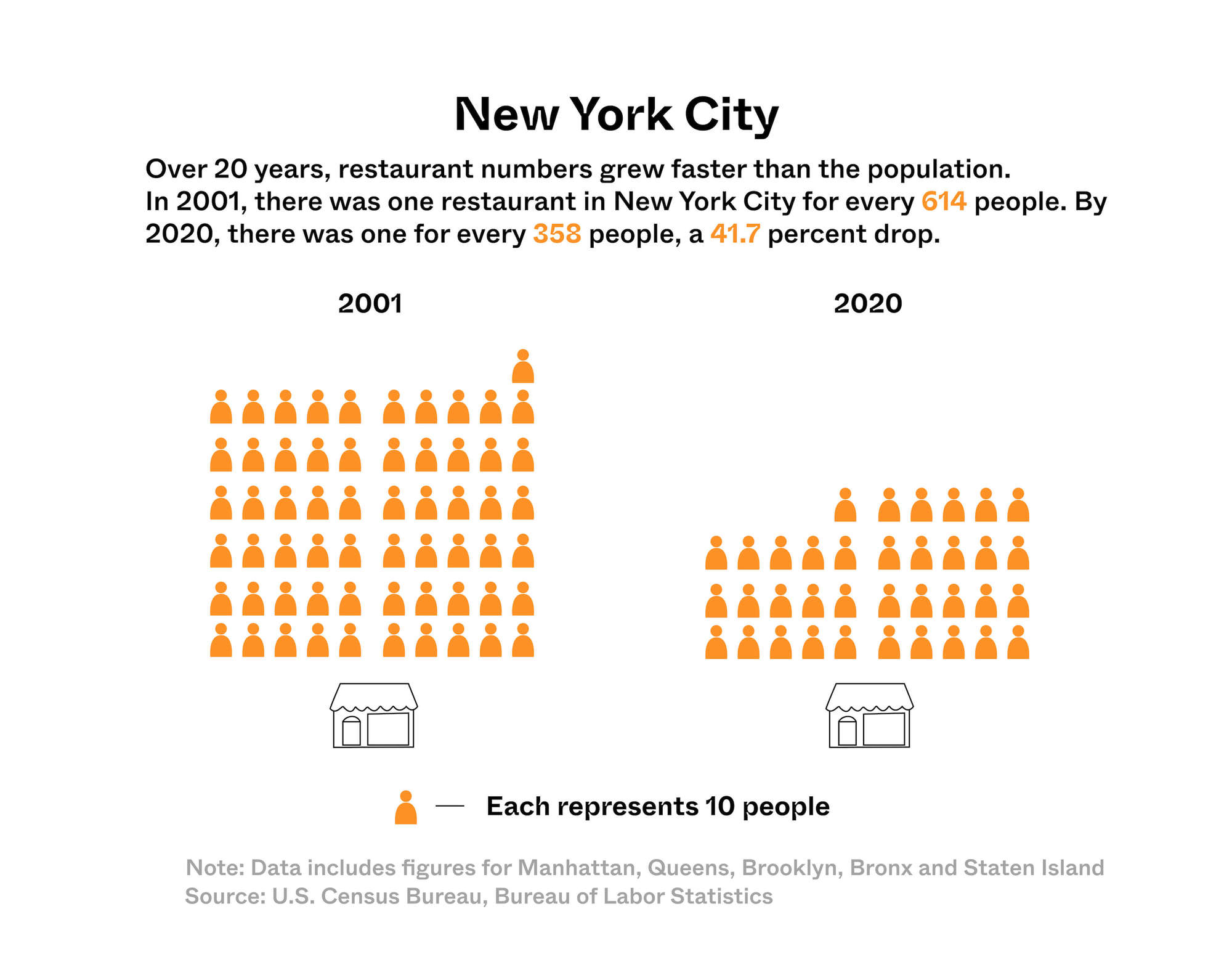

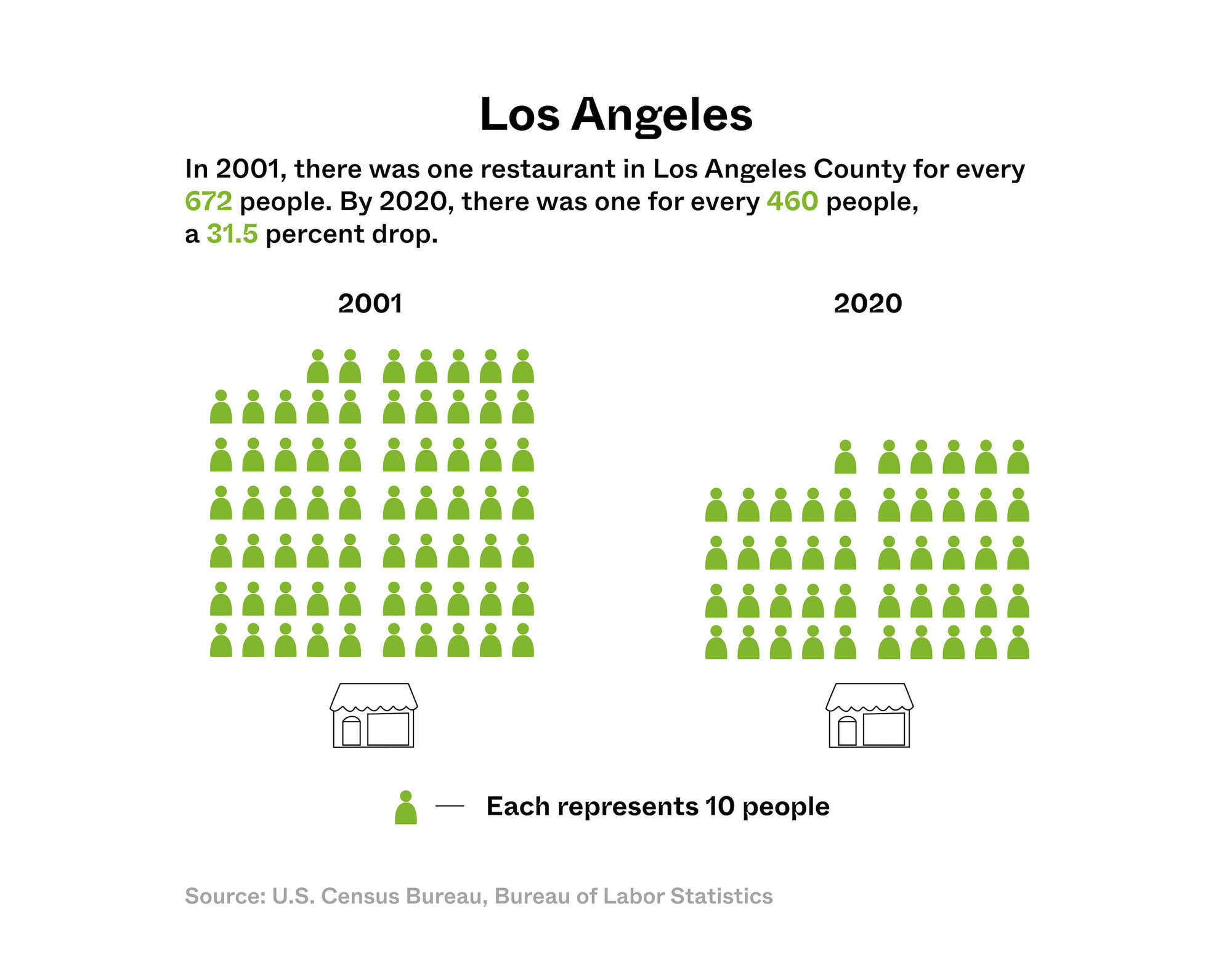

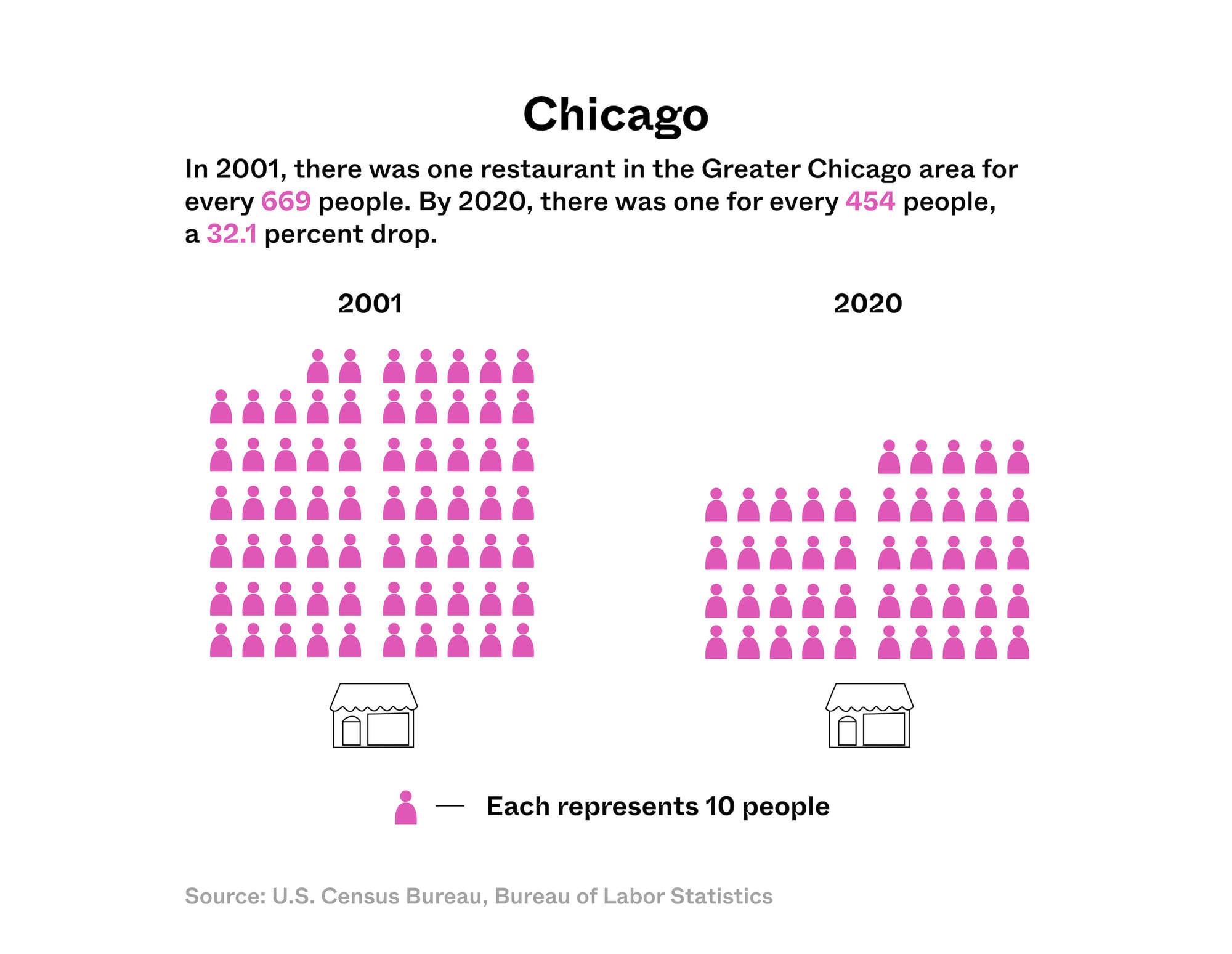

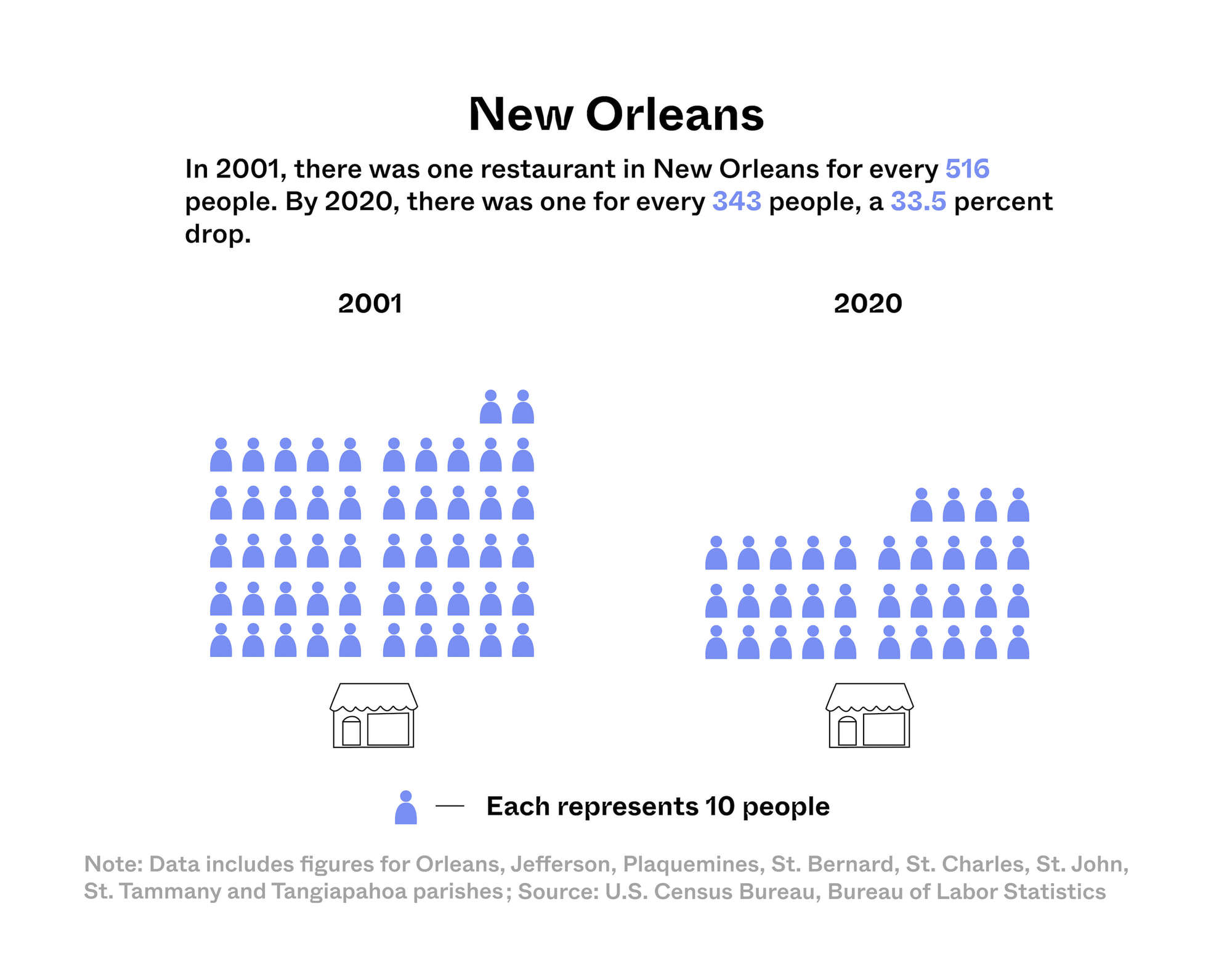

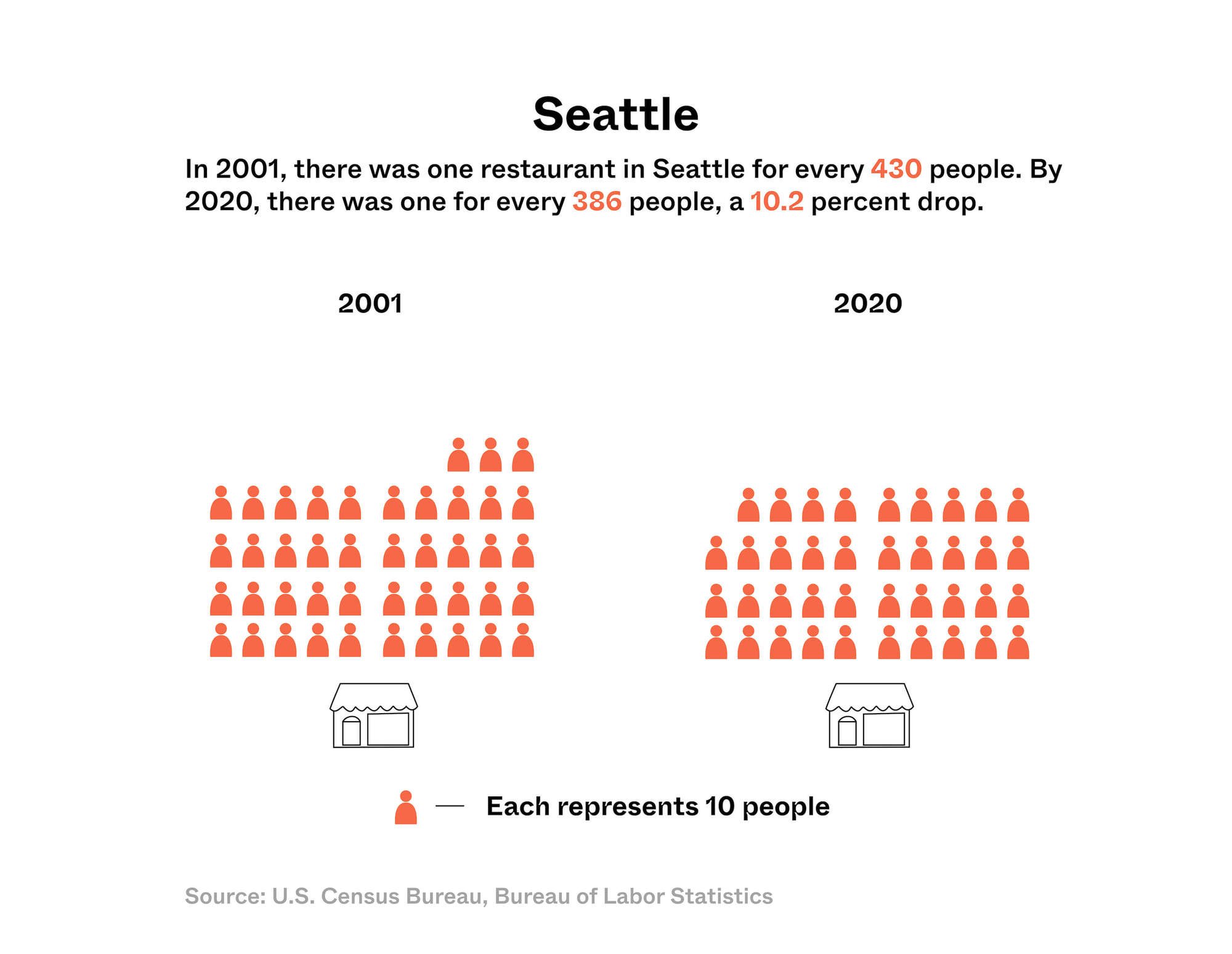

We ran some numbers of our own to see just how hard restaurants have to fight for customers, looking at restaurant and population growth in five urban areas over a span of 20 years—Los Angeles, Seattle, Chicago, New Orleans, and New York City. When we were done, we confronted a painful and unavoidable follow-up question:

Are there too many restaurants?

Looks that way.

Our data came from the U.S. Census and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which makes an annual count of “eating establishments.” We divided the population in a given location by the number of restaurants, year after year, to figure out the ratio of customers to places to eat.

All five samples tell the same story. Since 2001, restaurants have grown at a faster rate than the population they serve, which means fewer potential customers per restaurant today than in 2001. Back then, there were 671 customers for every restaurant in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago. In 2020, the number was down to 468, which makes the competition that much stiffer. Nobody can quantify exactly how many restaurants are too many to sustain, but we seem to have passed the saturation mile marker without noticing it.

The BLS numbers don’t even include the food trucks, corner carts, and pop-ups that make dining a moveable feast—and dilute a restaurant’s customer base even further. And they don’t reflect churn; the numbers look more stable than they really are, because new places aren’t added on top of an existing total each year. The tally doesn’t say who took over a lease from a failed restaurant, or how many chain outlets colonized a block that used to be full of local businesses.

Numbers don’t lie, but they are hard-pressed to convey context.

If this were the stock market, we’d be anticipating a correction, according to Stephen Zagor, a restaurant consultant who teaches a graduate-level class on food entrepreneurship at Columbia Business School. “Even before the pandemic, businesses were suffering from incredible competition, hanging on by life support,” he said. “What was evolutionary has become revolutionary, as trends that were rolling along put on afterburners and went into high gear.”

More aid might keep more places on their feet, for a while, but it isn’t a panacea for tough competition, which turns out to have survived even the shutdowns of the last two years.

Beth Wagner knows it. She and her husband run Chicago’s Honky Tonk BBQ, which has a head start on success: Two appearances on the television show Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives made a neighborhood place into a tourist destination; Beth owns the building, which eliminates landlord hassles; they have a existing catering program they can expand. Even with those advantages, they’re down to three nights a week instead of six, had to reduce their staff, and took a $300,000 Small Business Administration loan on top of the aid they received.

Wagner is a staunch supporter of OFW’s campaign for $25 an hour, but said she can’t pay it, not yet, nor can she afford to abandon the tipped minimum wage, though she tops off wages for employees who don’t make enough in tips to reach a $16 hourly threshold.

Polmar worries about owners who go into debt to stay afloat, to say nothing of the ones who sell possessions to do so; she also worries about what will happen on a larger scale if they fail, and operations with bigger pockets step in to feed us. Polmar can’t stand the idea of “a very cookie-cutter, homogenized restaurant landscape,” she said, dominated by replicable national chains, where dining out becomes a transaction rather than a neighborhood experience. She can’t stand the idea that we’d turn our backs on the next generation of small businesses and the diversity they represent.

She knows how much work restaurants have to do to improve their own culture, but they can’t do it if they go out of business. “Let’s save the businesses and then make them work in ways that are more equitable, sustainable and resilient,” she said. “If we don’t save them first, we have nothing to work with.”

Since 2001, restaurants have grown at a faster rate than the population they serve, which means fewer potential customers per restaurant today than in 2001.

Congress didn’t step up this time, despite all the lobbying and celebrity testimonials and individual elected officials’ support. Which leaves survivors where, exactly? Food costs, wages, and rent are going up, which means higher menu prices, and that, in turn, increases the risk that a diner will decamp for a burger that’s just a bit cheaper, down the street. If anything, competition for an already shrunken customer base is about to get even tougher.

The old model—think of it as eat, pay, leave—may not be up to the task. Zagor believes that restaurants need to be more elastic, to incorporate some of the pandemic’s greatest hits, including a curated market component or wine shop, meal kits, catering, stepped-up take-out and delivery. At the same time, they need to get lean: Austerity is essential, whether the cutbacks involve the size of the staff, the cost of ingredients, or even the decision to close an hour early because there aren’t enough late-night customers to justify the cost of staying open any later.

And yet nobody seems ready to give up, despite a daunting and unsubsidized future. Three hundred students signed up for the 75 seats in Zagor’s food entrepreneurship course, and when most of them didn’t get a spot they appealed to the dean for more sections, which they got, rather than sign up for another class. And preliminary BLS data for the first two quarters of 2021 shows a slight uptick in eating establishments in four of our samples—people continuing to open restaurants even as existing ones struggled to stay afloat. Among the five cities analyzed by The Counter, only New York City saw an overall decline in restaurants, a net loss of 881 places.

Nobody seems ready to give up, despite a daunting and unsubsidized future.

We all bear some responsibility for this. Chefs have entered the lexicon alongside other celebrity-fueled pipe dreams—Oscar-winning actor, basketball star, songbird—elevated to that rarified status, over 20 years, by food television, and social media, and restaurant-chasing as a competitive urban sport. We’ve become more demanding, more fickle, expecting an array of choices right this minute, which makes it easy for an aspiring restaurateur to mistake our restlessness for reliable demand.

Drive dies hard, even in the face of sobering numbers. Surely bad news is meant to happen to someone else.

That kind of denial seems essential, in the face of Wednesday’s disappointing news. The alternative is pre-emptive surrender, restaurant people turning away from work that was never the safe choice in the first place. Why would anyone suddenly become logical about an illogical commitment? If you regard restaurants as an essential third place—not home, not work, but a gathering place that celebrates friendship, family and a sense of community—you can’t really afford to see the glass as half empty, even though it likely is, for some places, for who knows how long.

F. Scott Fitzgerald never wrote about restaurants, as far as I know, but he had the current dilemma down cold. In “The Crack-Up,” a 1936 essay for Esquire magazine, he wrote, “. . .the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.”

Data reporting and visualization by Karthika Namboothiri.