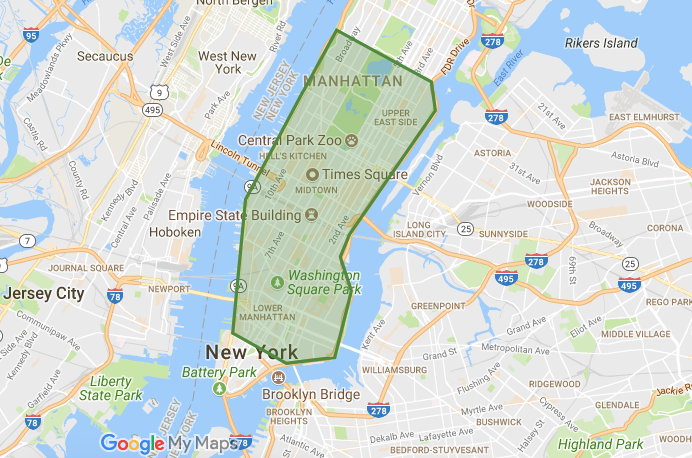

Google Maps

After two election cycles, most New Yorkers are probably sick of Mayor Bill De Blasio’s mantra: Gotham is a tale of two cities. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer, yada yada.

And nowhere is that more clear that in concurrent housing and homeless crises.

But what of the small business owners? The folks just trying to eke out a living in the big city? Shouldn’t they get a fair shake, too? Since last week, when the mayor carried two-thirds of the city, coasting into a second term in office, local politicians have seized the opportunity to get in on the ground floor of a new legislative agenda, and renewed a push for him to drop a commercial rent tax—an additional levy on businesses that some call the “most unfair tax” in New York City—and in particular, to exempt the neighborhood grocery store.

That can make running a business here a high-stakes nightmare. Dan Garodnick, a city council member who introduced a bill earlier this year to raise the threshold to $500,000, said expenses like the CRT are the reason why banks and chain drugstores now dominate city storefronts, as The Real Deal, a publication with a focus on Gotham real estate, reported in March.

There’s an argument to be made that a commercial rent tax is useful in places that might be facing budget shortfalls. In Florida, for example, the state levies a 6-percent sales tax on commercial leases—but then, Florida is one of the few states that doesn’t collect income tax.

In the ‘90s, Mayor Rudy Giuliani began repealing the tax, piece by piece across the city, but stopped short of exempting thousands of Manhattan businesses, leaving the tax in place as commercial real estate became increasingly cutthroat, with rents pointing steadily toward the sky.

It’s another story of unintended consequences: Today, council members and business leaders say the tax is unfairly punishing independent businesses in a competitive marketplace.

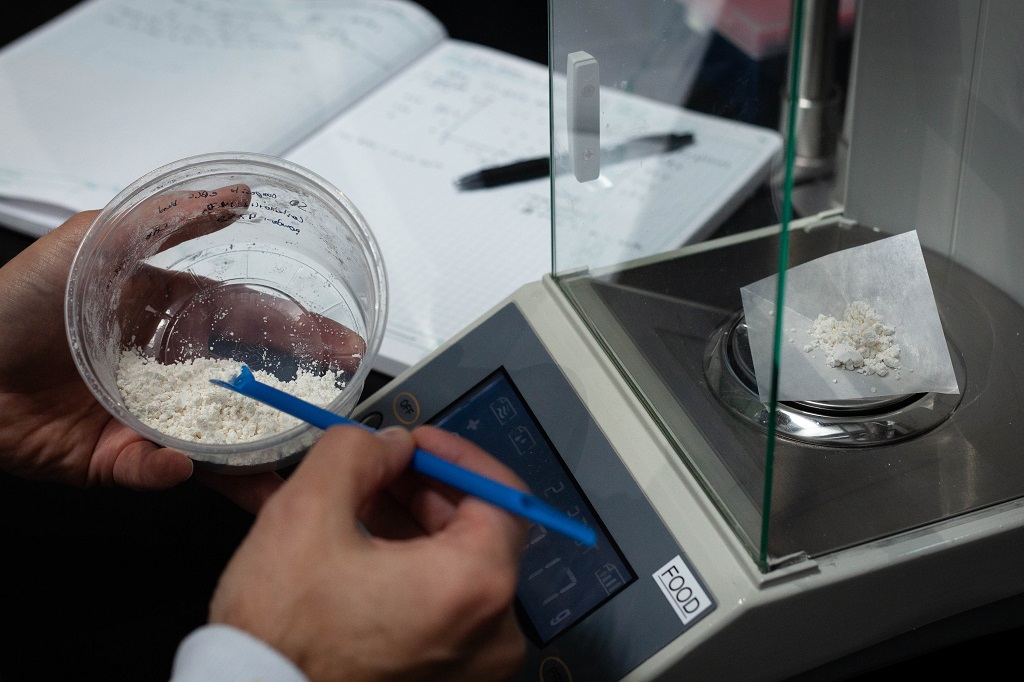

Enter the grocery store. A survey conducted by the office of Gale Brewer, the Manhattan borough president, found that 132 of them in the city are affected by the CRT. Calling them “essential businesses,” she rallied on Monday behind a City Council bill, first introduced in February by Councilman Corey Johnson, that’s proposing to exempt grocery stores from the tax altogether. (The council’s recent move could be seen as a response to local outcry over a rash of recent closures of affordable neighborhood grocery stores. New Yorkers are a nostalgic tribe. Curbed, a local real estate website, even started tracking the city’s disappearing local grocers last year.)

Eight years ago, one independent grocer says, a Whole Foods moved in around the corner, and his monthly rent skyrocketed

Brewer was joined by representatives of the National Supermarket Association (NSA), a New York-based coalition that represents 400 independent grocers in cities across the eastern seaboard. NSA believes the tax is hitting its members especially hard. Take a look at the member list, and you’ll see a cornucopia of old-school, low-cost grocers, from Foodtown to, uh, Met Food. It’s hardly the province of specialty stores.

Paul Fernandez operates Ideal Market supermarkets in Brooklyn’s Ditmas Park and Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhoods, and, until recently, a 5,500-square-foot Met Food in Manhattan’s Nolita neighborhood. Eight years ago, he says, a Whole Foods moved in around the corner, and his monthly rent skyrocketed, a sevenfold increase from $9,000 to $63,000. If that sounds nuts, it is. (New York is, after all, home to “The Rent is Too Damn High” political party.)

When I asked Fernandez why he’s waited until now to call for an end to the CRT, he didn’t cite Amazon’s recent takeover of Whole Foods, or other pressures from online shopping. Instead, he says, it’s the rising cost of labor in New York state, slated to hit a $15 minimum wage in the next five years: “That is very difficult for a small business to absorb. Such thin margins in such a small amount of time.”

Possibly, it could just be the beginning of a larger campaign to save the city’s independent grocery stores. Brewer’s office is considering creating zoning incentives to put more of them into the city’s myriad new glass towers and mega-developments, inspired by similar measures to address food insecurity in underserved neighborhoods.

Think of it as a cousin of De Blasio’s crusade for more affordable housing. Affordable retail, perhaps?