Historic flooding is submerging parts of the Midwest and Great Plains under inches of water. Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin—among America’s most valuable and productive farm states—have declared states of emergency. Parts of Iowa have been declared disaster areas.

By now, you’ve seen the photos. Vast fields covered in water, with grain silos and barns sticking up through the glassy surface. Warming temperatures melted hard-packed ice, and, in combination with recent rains, have caused a deluge that has overwhelmed rivers and levees and spread across the plains. The inundation is visible from outer space.

Nebraska has been hit hardest. The strongest, most intense waters have come from the failure of the 90-year-old Spencer Dam. After the “bomb cyclone” poured rain across the state, the failure of the dam ignited a flash flood that emptied into the Missouri River, and linked up with snowmelt from South Dakota and Iowa. Now, large swaths of the state are underwater. Three of the four deaths caused by the floods have been here. Hundreds more have left their homes.

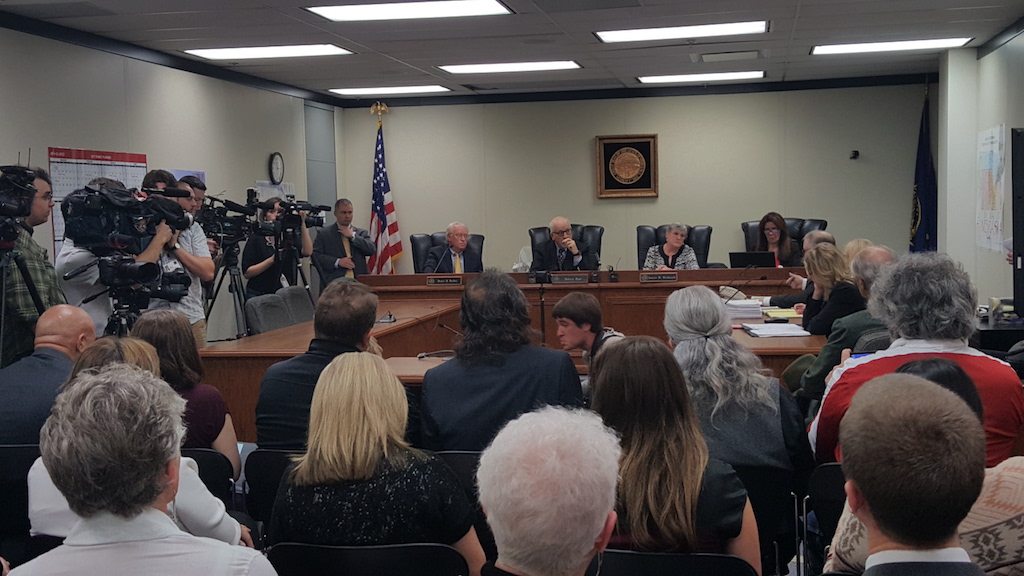

Jane Fleming Kleeb, Chair of the state’s Democratic party, tweeted that the historic losses faced by Nebraska families “will impact food on your table.” Farmers have already suffered over $1 billion in corn and livestock losses, with additional economic losses expected. There are 79,000 miles of waterways in the state—and more rain is forecasted to be on the way.

The flooding couldn’t come at a worse time for growers. Farms filing for bankruptcy rose by 19 percent last year across the Midwest, the highest level in over a decade, according to the American Farm Bureau. The ongoing tariff battle with China has made one of the country’s riskiest and least predictable professions even more unstable, and the U.S. government hasn’t been buying their crops. But it’s also a particularly tricky time in the growing season: the onslaught has arrived just before spring planting, when farmers should be preparing to put seeds in the soil.

“Some of these places need an extended period of dry weather to get fieldwork started,” Dan Hicks, a meteorologist, told Bloomberg. “But I don’t see an extended dry spell.”

It’s not just that water is soaking the farms. The floods are destroying the network of farming infrastructure. “The rail lines and roads that carry their crops to market were washed away,” The New York Times reported from Nebraska. Farmers have been cut off from their animals “behind walls of water,” and others can’t get into town to buy supplies. Where highways and roads have been flooded, the National Guard has been airlifting hay and animal feed to marooned farms.

How did this happen? Mindy Beerends, a meteorologist, told The New York Times that these rains have been so devastating because there hasn’t been anywhere for the water to go.

The problem actually began to take shape in the fall, when Nebraska was inundated with heavy rainfall. The soil was saturated with water just as winter rolled in, freezing the moisture underground. Then the plains were covered in snow. As spring has come along, and snow has melted, the resulting water hasn’t had anywhere to retreat to.

Omaha, which averages less than an inch of rain in March, has already seen over two inches this month. The flat, frozen plains have been unable to soak it in, and runoff has quickly filled rivers and streams.

Nebraska has 6.4 million head of cattle, making it the second-largest cattle state in the country. It’s also the country’s third-largest corn-producing state—the crucial ingredient in feed. To understand what these floods mean to ranchers, Laura Reiley of The Washington Post spoke to Anthony Ruzicka, a fifth-generation Nebraska rancher.

“There’s not many farms left like this, and it’s probably over for us too, now,” Ruzicka told another reporter. “Financially, how do you recover from something like this?”

Ruzicka’s own alfalfa and corn fields—the feed for his cattle—were filled with ice chunks. After the water subsides, and the floodwaters recede, grain farmers will have to clean their fields, and get a late start on planting. Both will mean significant costs. Waterlogged fields can rot, mold over, or fail.

“The water is chock-full of stuff. This is a toxic brew that is going down the river—the water took out gas stations and farm shops and fuel barrels,” John Hansen, president of the Nebraska Farmers Union, told the Post.

It’s hard to see a clear path to recovery. So far, in Nebraska alone, early estimates have put ranching losses at around $500 million, and losses to grain farmers could be around $400 million, the Nebraska Farm Bureau told the Post. It could be months, or even years, before farmers rebound.

If you’re a farmer looking for help, the University of Nebraska has links for flood resources available online.