Alex Fine

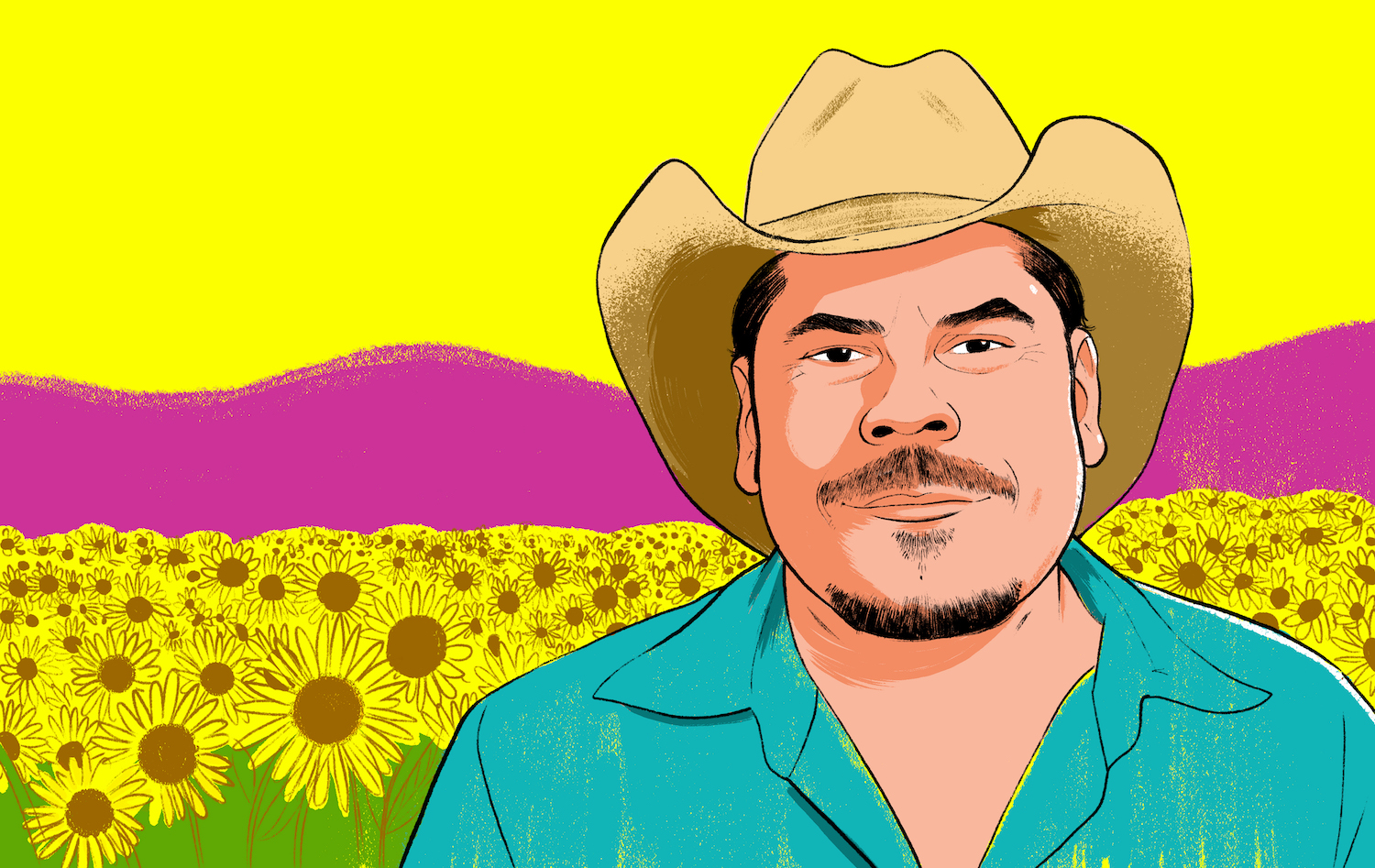

When Jaime Ortega, age 45, undertook the dangerous journey to the United States, he had never left the small town in Northern Mexico where he was born. He was no stranger to agriculture, having worked in farming from a very young age. But the farms he encountered when he arrived in Wisconsin were a world away from what he knew.

“When I came to the United States, it was so different,” Ortega says. “In Mexico, we used horses and bulls to work in the fields. Here, it was big tractors, machines—it was easier, faster, to do the job. You didn’t get tired the way I did growing up.”

Like many new immigrants to the U.S., Ortega found on-farm seasonal work. Nearly 70 percent of farm laborers in this country are immigrants; nearly half of those workers are unauthorized. Now, though, Ortega’s days as a hired farmhand are behind him. Here, he tells the story of how he met his wife, Natalie, with whom he runs a farm called Natalie’s Garden and Greenhouse. Their 29-acre plot in Oregon, Wisconsin, grows a range of crops sold in local farmers’ markets, from fresh flowers to collard greens and cantaloupe, as well as many of the vegetables Ortega first learned to grow as a child—zucchini, tomatillos, peppers, and corn.

This conversation has been translated, edited, and condensed.

~

Jaime: I had a rough childhood—we were very poor. I didn’t own a pair of shoes until I was 16. I got a year and a half of schooling before my father took me out to start working the fields. I was three years old. It was a cornfield where we raised corn, and beans, and squash, and I was there to pull weeds around the plants, bring water up from the river, and scare away the cows and donkeys who might eat the crops. I never went back to school.

One of my older brothers, Manuel, had migrated to the United States. In 1994, when I was 21 years old, he came back to Mexico. I had been looking to leave and was thinking of going to Guadalajara to work in construction with my cousins. My mother was suffering—she had diabetes and other ailments—and needed help. Manuel said there was work in the U.S. and asked if I wanted to go back with him.

A coyote [human smuggler] took us into Nogales, Arizona, through a sewer. There were 40 or 50 of us. It was terrible—one guy tried to rob us at knifepoint. From there, we went to California and then to Wisconsin, where my brother had found work for us.

We arrived in March of 1994. It was cold and snowing, and for the first three months I told myself I would go back to Mexico as soon as I got my first paycheck.

But then summer arrived. It was warm, and everything was turning green. I found work on three different farms and was earning good money. During that time, my boss’s daughter, Natalie, moved back home to Wisconsin.

Natalie had just left her husband. She was pretty and I liked her the minute I met her. But she was my boss’s daughter so I thought it was best to keep my distance. I didn’t have any illusions of finding a girlfriend.

We spent a lot of time together, she started to learn a little Spanish and I learned some phrases in English. I asked her out and she said no. The following winter I found work on a farm in Edgerton, Wisconsin, bundling chewing tobacco. I started looking for excuses to go and see Natalie. I would bring her flowers on holidays.

I went back to Mexico for three months to build a new house for my mother and when I returned to Wisconsin, Natalie had bought her own farm. She asked if I could help her out, and then we started to date.

We married in 2003, and today we have a 16-year-old daughter, Isabel.

We also have 29 acres of land. We mostly plant vegetables—cucumbers, carrots, broccoli, sweet corn, cauliflower, and cabbage—and sunflowers. We work hard and are tired, but at the same time are content with all we’ve achieved.

We sell our produce and flowers at several farmers’ markets around Madison and donate our extras to local food pantries. I’m happy to be able to help people who don’t have enough to eat.

I arrived to this country with nothing and, through my own sweat and hard work, now have what I need to live. I’ve built meaningful relationships with my customers, other vendors, and managers at the markets over the years. I have friends here who trust me and whom I trust.

Yet every day when I drive to the markets I’m afraid of being pulled over. I don’t have a driver’s license because I don’t have documents.

Some Americans see immigrants as people who have come to take away something that belongs to them. This is a country of immigrants. People say this is the best country in the world, but that’s because of people like me, people like you, people who read this, who focus on work, who do good.

My wife and I have been trying to legalize my status for years, but it’s complicated. I wish I could come and go freely to Mexico, instead of hiding like a rat. I lost my mother three years ago. I was here, swallowing my sadness and helplessness over not being able to go and see her because I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to get back to my farm in the U.S.

When you’re born, God gives you freedom to enjoy the world—not just the country you were born in. I don’t understand why man created borders.

In the future, I want my daughter to appreciate who I am and where I come from and the values I have taught her. I want her to be a good, sensitive, honest, hard-working person. I want her to know I did all this to give her a better life than the one I was born into.