Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock, Jeremy Chiu

Cutbacks have defined the pandemic era restaurant—but when owners invest more in their employees, everybody wins.

Like many restaurant operators over the past two years, Greg and Daisy Ryan, co-owners of the French-inspired bistro Bell’s in Los Alamos, California, sweated over how their business would survive a global pandemic. All around them owners were turning to takeout, to retail, or to closing their doors indefinitely.

The Ryans, meanwhile, decided to spend more money—actually, a lot more money—on their staff. They hiked wages to an average of $27 an hour. They added on a bevy of new perks, including fully paid health care coverage and 80 hours of paid time off.

Increasing costs is risky business even in good times for restaurants, where profits margins are sometimes thinner than mandolined potatoes, and the industry was on life support even before government-mandated shutdowns were part of the conversation. But the Ryans made their drastic changes back in June 2020, after a two-month in-dining closure to regroup, deciding to spend big when most independent restaurants were scrambling to meet existing costs.

Daisy Ryan is the Executive Chef and co-owner of the French-inspired bistro Bell’s in Los Alamos, California.

Bonjwing Lee

It worked. Bell’s revenues and staff have more than doubled since that pivotal summer day, and now the Ryans are talking about how to add a retirement program with four percent matching funds, a longstanding goal that will also bring them in line with state-mandated legislation.

“We said, ‘If we’re going to change, this is our time to change,’” Greg said. “If we are not trying to be a better business, and a better business for our staff and the people that work with us, we are going to be so upset with ourselves.”

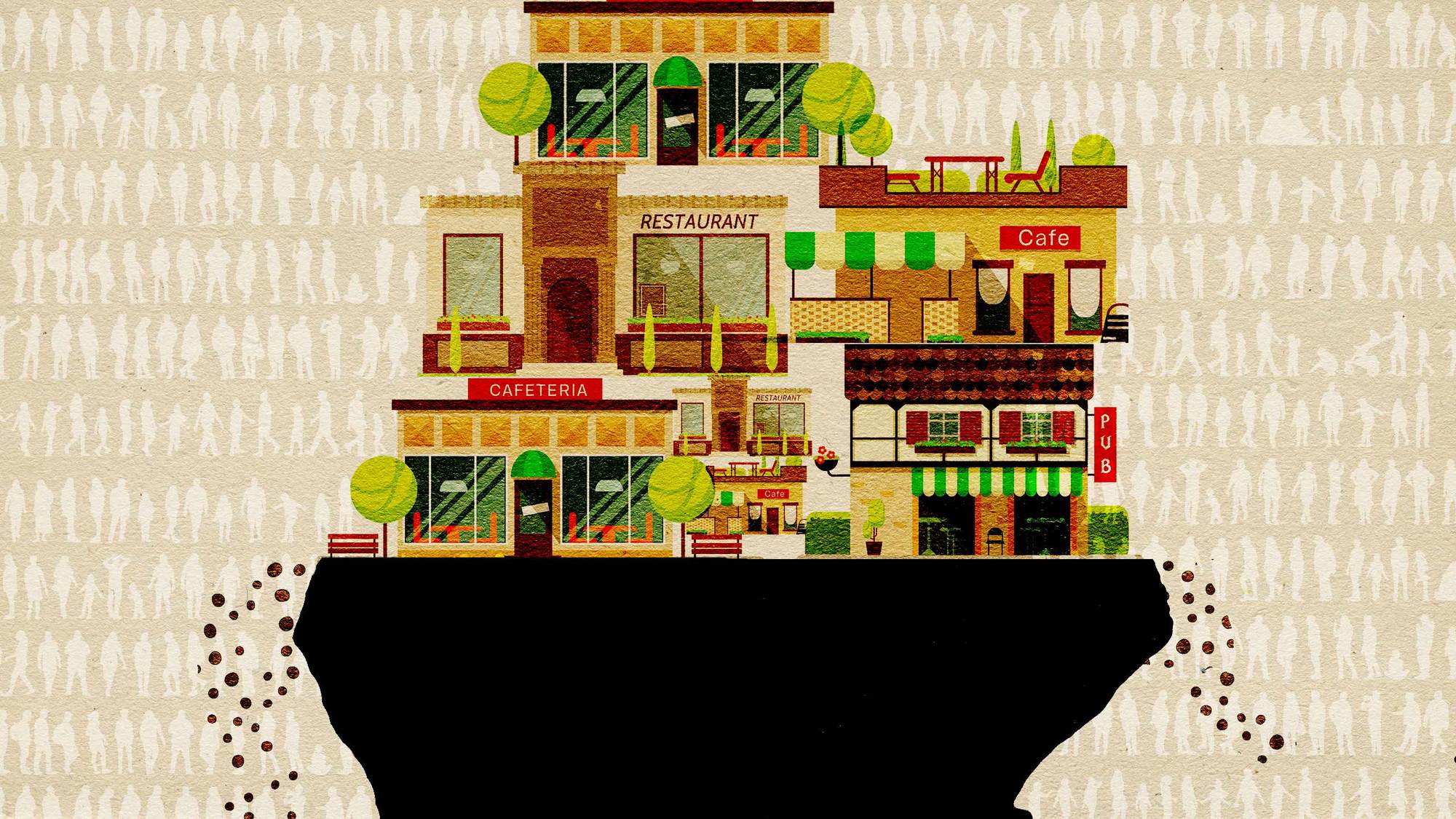

Even before Covid upended the restaurant landscape, operators large and small were staring down the growing burdens of dwindling foot traffic and poor staff retention. The pandemic, however, turned those concerns into crises.

They hiked wages to an average of $27 an hour.

Revenue shrunk, debt mounted, and employees, fed up with the industry standard of shoddy pay, grueling hours and nonexistent benefits—not to mention having to risk their health for poor compensation and rude customers—hung up their serving aprons and chef’s whites for good. With the food service industry still down 819,900 jobs as of this March compared to February 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and any future federal aid uncertain, restaurant owners like the Ryans were left to find their own alternatives to the old, dysfunctional model.

Many operators have seen a chance to experiment and lay the foundation for a more sustainable industry, which means starting with the individuals who keep it afloat: A healthy staff—physically, mentally, financially—will be far more likely to contribute to long-term success than a team running forever on fumes.

The Ryans built a formula: They figured out how much they’d have to bring in from each seat, down to the penny, to break even, while they guaranteed all their employees more than a living wage along with benefits.

The couple performed back-of-the-envelope math while plugging into a Google spreadsheet hard costs like real estate, and more flexible ones like food and labor. They consulted with an industry brain trust of former and current management from Union Square Hospitality Group and the Thomas Keller Restaurant Group, as well as the restaurant operations support group Oyster Sunday, about what the ideal model would be. And they arrived at a surprisingly simple solution that many restaurants have turned to throughout the pandemic: a pre-fixe dinner menu.

The Ryans figured out how much they’d have to bring in from each seat to break even, while they guaranteed all their employees more than a living wage along with benefits.

Carter Hiyama

At $65 for five courses, plus a 20 percent overall service fee in lieu of tips, the price and format felt like a deal that guests could swallow. And, Greg said, it meant that “I’m at least breaking even or I’m not losing a ton of money every second.” The pre-fixe operation not only has helped the team better manage their food costs, but the consistency means they can regularly plan to source salad greens or uni from local producers they’re confident in, versus buying commodity vegetables to accomodate a constantly rotating menu. The service fee, while carrying a significant drawback in that it is reported as income, meaning Bell’s has to pay taxes on it, was a major boon because it removes customers from having any power over their staff’s wages and ensures a guaranteed—and more transparent—revenue stream to help pay for employee costs.

As of October 2021, the menu now runs $75 per person—the $10 increase due to inflation and growing food costs, with 65 to 75 covers a night. Greg says that the menu price is effectively their break even point, while add-ons like wine, caviar and bread all help to ensure profitability. The new model looks like a success: As the staff—and the total restaurant’s costs—have tripled, the number of customers per night has jumped from the ballpark of 40 in June of 2020. Revenue more than tripled as well: Before Covid, in 2019, the restaurant was clearing $1 million a year. In 2021, despite an on-going pandemic, that number surged to about $3 million. And employee retention has been above 95 percent.

Greg regularly points out that privilege and good fortune have played a part as well. Early on, he and Daisy purchased the building housing Bell’s instead of buying a home, essentially locking in their real estate costs; their decision to live with Daisy’s parents in the meantime has also helped reduce their overhead costs. The publicity from Daisy being named a Food & Wine Best Chef and Bell’s earning a 2021 Michelin star has helped ensure a continued demand for their food while also allowing them to expand their revenue. And a $93,000 Paycheck Protection Program loan as well as a $150,000 Economic Injury Disaster Loan, along with private funding, helped provide the cash flow to implement these huge workplace overhauls.

“A dinner restaurant sit-down table service is one of the highest labor versions of what we could be doing, and we want to, as we grow and expand, think of things that can keep labor tight.”

“If someone’s like ‘What’s the blueprint?’ I’m like, it’s a lot of luck, it’s a lot of hard work and it’s just being in the right place at the wrong time, but also the right time,” Greg said.

Still, it’s possible to innovate on more of a shoestring. Stella Dennig, co-owner of Daytrip, a restaurant and wine bar that opened in Oakland, California last October, listed several experiments the restaurant has incorporated to expand its revenue streams, including beverage clubs curating natural wines, beer and aperitifs and a pop-up nighttime wine bar with a menu of easily preparable snacks. She may start a coffee and pastry service as well, which won’t require a full back-of-house team to prepare the food.

“A dinner restaurant sit-down table service is one of the highest labor versions of what we could be doing, and we want to, as we grow and expand, think of things that can keep labor tight,” Dennig said. “Every five hundred dollars, every thousand dollars all makes a huge difference, so the more revenue streams that we can pull in, that can do that for us every week, every month, it all adds up.”

Dennig estimated that Daytrip’s employee costs range from 40 to 48 percent of the restaurant’s total costs on a good week, greatly exceeding the conventional industry figure of 30 percent. The non-salaried staff starting base wage of $16 to $18 an hour, slightly higher than the $15.06 minimum wage in Oakland, is bolstered by a 20 percent service fee that is pooled and evenly divided among hourly staff. The restaurant also provides access to quarterly financial workshops and a scaling health care stipend, which totals $300 a month for an employee working 40-hour weeks. Retirement plans are a possibility down the line.

At Daytrip, non-salaried staff have a starting base wage of $16 to $18 an hour, slightly higher than the $15.06 minimum wage in Oakland. This wage is bolstered by a 20 percent service fee that is pooled and evenly divided among hourly staff.

Jeremy Chiu

“There’s so much more that I would like to do and that I know that we will get to,” Dennig said. “All I’m doing right now is what feels like the bare minimum to me, and it’s revolutionary only because the bar is so low in this industry, and that’s not OK.”

Investing in staff wages and benefits can result in a virtuous circle effect: People are more likely to stay at their jobs, which then decreases the costs that result from replacing them. Tim Taney, co-owner of the burger restaurant Slidin’ Dirty in Troy, New York, estimated that training new employees cost him at least $500 a month. A year after expanding his staff’s benefits package to include employee-covered health insurance and a membership to the YMCA, among other perks, staff retention has improved drastically, with only one employee leaving during that time.

“It’s a significant savings,” Taney said. “It certainly doesn’t pay for everybody’s health care for the year, it’s not like that alone covers that, but it’s a part of it.”

Connor Studios

Jason Berry is the co-founder of the Washington D.C.-based restaurant group Knead Hospitality + Design.

Jason Berry agrees. Earlier this year, the co-founder of the Washington D.C.-based restaurant group Knead Hospitality + Design, began a six-month experiment at its Mi Vida and Succotash National Harbor restaurants, allowing managers and chefs to work four-day, 12-hour shifts per week and finish up any lingering tasks like staff scheduling or menu planning outside of the restaurant, versus five 11- to 12-hour shifts per week, all on site.

Berry estimated that the new program at Mi Vida will necessitate adding three new managers, each at an annual salary of about $80,000. Improving employee retention, however, would mean cutting down on training costs and recruiter commissions, which run 15 percent of each new hire’s salary. And keeping people around has other benefits, like preserving a chef’s institutional knowledge—dialing back the amount of seasoning in October, for example, when chiles are spicier.

Channeling his inner Henry Ford, Berry suggested that investing in employees will ultimately lead to better service and, hopefully, better revenue.

“They’re less exhausted, they’re more focused on their teammates, they’re training better,” Berry said of a staff with a better work-life balance. “Does that translate into more revenue? I think it does.”

Indeed, workers at restaurants that recently have invested in their staff—from better wages to paid time off to retirement plans—say that these changes have not only improved their physical and mental health, but also their entire relationship to their job.

“I’m proud more than anything that I have a job that respects me enough that pays for my health insurance.”

Micah Fendley, a server at Bell’s, has been in the industry for about 20 years, and thanks to the changes there has a health insurance card for the first time. That’s affected not just his physical well-being but his outlook on his job and employers, too.

“I’m proud more than anything that I have a job that respects me enough that pays for my health insurance,” Fendley said. This past February, while the restaurant staff was on a paid winter break, Fendley traveled to Six Flags with his girlfriend, washed his car, had lunch with coworkers, even played disc golf. Returning to the restaurant post-break, he said, “I was able to have an out-of-body experience at work because I was so well rested.”

Anne McBride, vice president of programs at the James Beard Foundation, noted that not all improvements for workers require employers taking on immense additional costs. Citing findings from a recent report by the organization, McBride said that a number of people left the industry in recent years because there were not clear career paths laid out for growth at restaurants. By simply instituting structures for employees to progress to higher hourly wages or positions, restaurants can turn jobs into careers and reduce turnover.

By simply instituting structures for employees to progress to higher hourly wages or positions, restaurants can turn jobs into careers and reduce turnover.

“It’s something that restaurants should pay much closer attention to because, not that it’s free, but it’s something that you can do without having to change anything to the financial structure of your restaurants,” McBride said.

Greg Ryan is encouraged by how the restaurant’s transformation has bettered the lives of Bell’s staff, but he’s already thinking about what more he can do.

“We hope to get to dental and vision, we’re finally working on our 401(k) program,” Greg said. “It’s all these things that make people feel and hopefully see that there is a reinvestment going back into them as people and not some cog in the machine.”