Angela “Nike” Sutton is losing her Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, commonly known as food stamps) benefits next month. “They already cut my food stamps down from $500 to $33,” she says, adding that she has a new job working for the New Jersey Turnpike.

Sutton has two children and says she’s used the program to help make ends meet for years, even though she’s been employed for a lot of that time. She lives outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and is a speaker for the advocacy group Witness to Hunger. “This stereotype of people that use SNAP benefits is that we’re lazy, that we just use a handout—some of us really want to work and get off this program,” she says.

Sutton says she doesn’t feel ready to lose her assistance. She’s paying off student loan debts and sometimes feeding other children in the neighborhood in addition to supporting two sons and paying her bills.

“After Uncle Sam gets his money, we still have bills to pay. Once we pay our bills, we have to make harsh decisions: Do we pay the electric bill? Or do we just buy a bunch of unhealthy food?”

As debates swirl in Congress over tightening work requirements in the next farm bill, it’s worth considering the group of people who already have jobs and still need food stamps to feed their families. They make up nearly half of the people who use the SNAP program in a given month. Why aren’t they earning enough money to meet this most basic need?

Sutton is a part of the subset of SNAP recipients who hold down jobs while receiving benefits. The New Food Economy recently obtained data on SNAP employers from six states via public records requests. We found that thousands of people who work in fast-food and retail jobs don’t make enough money to buy groceries.

We published the most striking results—that Amazon’s employees are heavily reliant on food stamps even though they’re working in jobs that typically pay family-supporting wages—in partnership with The Intercept. But we were also struck by what hasn’t changed since a spate of stories looking at the same questions were published a decade ago, when Amazon still seemed content with upending the book industry. Walmart and McDonald’s rank first and second for number of employees on food stamps in five states out of six, and other fast-food companies rank high on the lists of employers with the most workers using SNAP benefits.

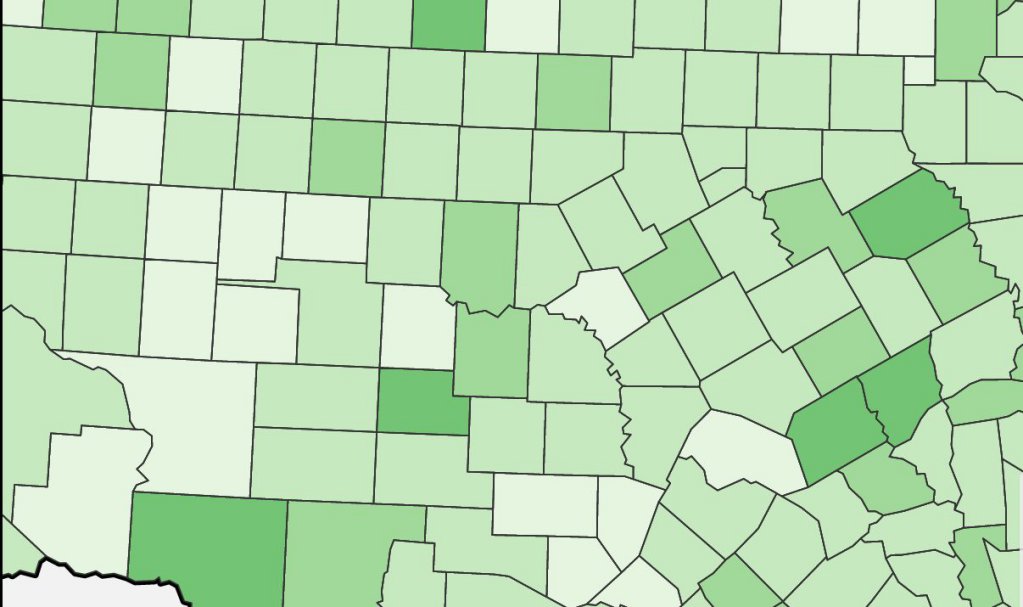

We received data from Arizona, Kansas, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, and Washington. Ohio’s data was already publicly available. In five states out of six, Taco Bell, Wendy’s, Pizza Hut, Burger King, Subway, McDonald’s, and Walmart all appeared among the top 50 employers of people using food stamps. Other companies in the food industry including grocery stores, institutional foodservice providers, and meatpackers were also represented.

In some instances, the companies whose workers are reliant on SNAP are the same companies that have been lauded in the past for paying better than the average fast-food job: Chipotle employed nearly 500 SNAP recipients in Ohio in August 2017, and Starbucks ranked 20th for number of employees most reliant on the program in Washington, ahead of Wendy’s and Pizza Hut. Outside of the food industry, one other notable startup appeared on the lists—Uber employed 1,214 SNAP recipients in Washington between 2014 and 2017.

In early March, Senator Ed Gomes joined legislators, activists, and working people to advocate in support of Senate Bill 321. The coalition is calling for the passage of a Fair Workweek bill, limiting an abusive practice known as “on-call scheduling” across Connecticut’s large corporate retail, food service, hospitality, and certain nursing home work industries

Overall, nearly half of all people who rely on SNAP already live in a household where someone works. That’s why, as the Republican Party strives to tighten work requirements in the program, critics call it a solution in search of a problem.

In fact, according to an analysis of one month of SNAP data by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) in March, 82 percent of households on food stamps had a working adult the month they studied. That number climbs even higher for families with children: 87 percent of those households had a family member working within a year.

The picture that emerges of SNAP usage in the CBPP report is very different from the narrative put forth in Washington. People aren’t using SNAP because they’re lazy and don’t want to work; they’re using the program for a few months at a time in between jobs, or at times when they’re already employed but simply don’t make enough money. That’s why the first letter in SNAP stands for “supplemental.” And often, the reasons for job turnover have more to do with the inflexibility of low-wage employment than employee delinquency—an analysis of the jobs that pay hourly wages and that fall in the bottom quartile showed that only 46 percent of them offered any form of paid sick leave.

High SNAP enrollment among employed people is about more than just low wages, though of course that’s a big piece of the puzzle. Low-wage work is unstable in several different ways that push people to rely on SNAP to fill in the gaps. Workers aren’t scheduled for as many hours as they’d like, sick-day policies are unforgiving, and shifts are inconsistent, meaning paychecks vary considerably from week to week. All these factors lead to high turnover rates in jobs that are typically part-time and low-paying to begin with.

“It’s all about the employers, who I think have the upper hand,” says Kathy Fisher, policy director at the Coalition Against Hunger. “They have more ways to look at, ‘well, when do we really need people?’ They’re making it work for them dollars- and cents-wise. But it doesn’t always work for worker,” she adds.

In Philadelphia, for instance, 74 percent of people working less than 30 hours wanted to work more, but weren’t given more hours on the schedule. That’s according to a study by researchers at UC-Berkeley that found nearly three-quarters of people surveyed in the retail and service industries experienced conflicts between their work schedules and caregiving responsibilities.

“If you’re only finding out your schedule the week of, or the week in advance, it’s harder to arrange healthcare, harder to arrange a ride into work,” Fisher says. And it’s even more difficult to pick up a second job if you can’t predict when you’ll have to be at your first.

The CBPP report found that people who use SNAP were relying on it more to bridge gaps between periods of unemployment than as a long-term alternative to work. Current federal policy ensures the program stays that way, too. Most unemployed adults without children can only use SNAP for three months in a three-year period unless they are working or training for work at least 20 hours a week. Those rules were relaxed during the recession and can be waived in certain areas with high levels of unemployment. A number of states have re-introduced work requirements as the economy has recovered.

Brynne Keith-Jennings, senior policy analyst at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and the author of the report, says a few minor policy changes would go a long way to help lift people out of poverty and, by extension, out of the SNAP program: Access to transportation, childcare, and stable housing. “To the extent that policymakers can help improve the quality of jobs so that they pay wages and provide more stability for workers, that would also help,” she adds.

Angela Sutton says access to childcare and consideration of student loans in determining SNAP eligibility would make the biggest difference in her paycheck. “I’m trying to get out of debt. I’m trying to get afloat. Y’all cut me off too soon. This is ridiculous,” she says.

Beyond raising the minimum wage, a few regions have taken action to address barriers to full-time work. New York City passed a suite of fair workweek laws that went into effect in January 2018. They require that employees know their schedule two weeks in advance, ban on-call shifts, and let workers contribute directly from their paychecks to a nonprofit that advocates on their behalf (kind of like a union). Fast-food companies now have to offer extra shifts to existing employees before hiring new workers, meaning a path to full-time employment has been enshrined in policy. Similar laws passed in the state of Oregon in 2017. According to Fair Work Week, an advocacy organization that pushes for work-week reforms, hourly workers have won fair workweek protections in seven municipalities and two states since 2014. These modest reforms still don’t solve the problem of childcare or unstable housing, but they’re a start.

Small improvements in the industry help, too: 12 major retail brands have ended on-call scheduling, and Starbucks adopted the policy of scheduling two weeks in advance and mandating eight hours of rest between shifts. Walmart announced in 2018 that it will raise its starting wage to $11 an hour, a move Target made in 2017.

At the federal level, members of Congress have introduced legislation that would encourage corporations to pay higher wages: the Corporate Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act, proposed in the summer of 2017 by California Representative Ro Khanna, a Democrat, would send businesses a bill for their employees’ cumulative burden on the safety net, The Intercept reports. Under those circumstances, Walmart would’ve been on the hook for $6.2 billion in 2013—roughly equal to what it paid in total federal income taxes last year.

Even as incremental improvements burnish corporate reputations and progressive polititans’s legacies, fear of automation looms large for people who work in jobs they fear might be replaced. “They’re all changing over to EasyPass, so we’ll be out of a job in the next four years,” Sutton says of her work for the Turnpike. “I’ll be right back to square one.”