Nina Sparling

When Brooklyn-based online farmers’ market Farmigo approached organic farmer Richard Giles with what looked like a small farm distribution solution, he didn’t see much of a downside. Giles could list his products on the company website and access new customers. He would drop off goods at a warehouse weekly and Farmigo would manage the delivery from there.

Giles figured Farmigo could help with the marketing and delivery logistics side of running his businesses: In addition to growing, he runs a food hub out of an old dairy barn on his farm in Hamden, New York. He aggregates and distributes produce both from neighboring farms and his own—this is his 18th season farming as Lucky Dog Organic. He started the Lucky Dog Hub to provide a sales avenue for his community. For a time, Farmigo worked.

Farmigo and other e-commerce-for-the-farmer companies have tried to build a supply chain through digital-first platforms, but have found that the high returns and scalability that venture capital investment demands are proving to be ill-suited to the low-margin, high-risk reality of small-scale farming. As software companies come and go with the ebb and flow of investment, the Hub has persisted—primarily by not being digital-first and instead moving product through a supply chain that relies on relationships. But while it draws on the rhythms, scale, and reasonable expected financial returns of the small farm, the operation still grapples with a constant stream of challenges.

Nina Sparling

Nina Sparling Lucky Dog Hub transports goods to downstate markets, which are a vital source of revenue for many upstate farms

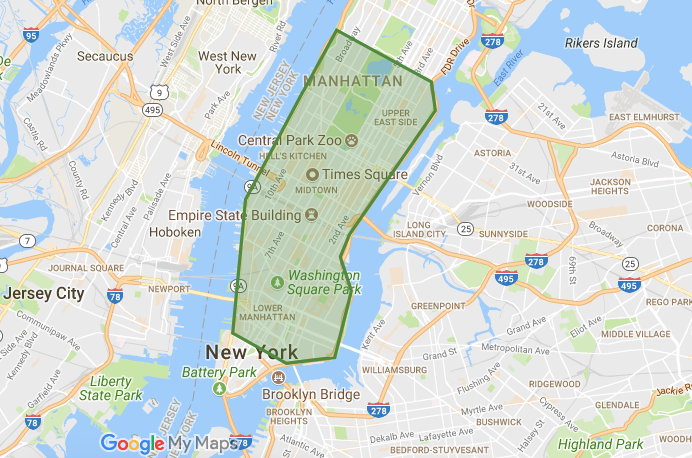

Giles built the Hub to solidify and amplify the flow of goods and capital between small farms in the Catskill region of upstate New York and restaurants and shops in New York City. Though buyers of local produce abound in the city, farmers struggle to both find customers and get relatively small amounts of product downstate. Despite the distance—Hamden is a 3-hour drive from Manhattan, half of which passes through the Catskill Mountains on curving two-lane highways—downstate markets are a vital source of revenue for many farms. There are a handful of nearby restaurants, but they are too few to support the local community of small farms, which in Delaware County tend to be small, delineated by rolling hills evocative of the regional history of dairy farming.

Giles knows firsthand the struggle farmers in his region face securing distribution downstate. He has always been a farmer (he managed commodity farms in Mississippi and Alabama prior) but had little experience in diverse vegetable farming in the cold and damp Catskill Mountains. “The climate up here tries to do everything it can to discourage you,” he says, “I had to learn all over again how to farm.”

For Giles, the Hub started with the truck. He has been driving his own produce down to New York City on a weekly basis for 18 years, where he sells at farmers’ markets and fulfills wholesale orders to restaurants and a handful of retail shops. Bit by bit, he started making space in his refrigerated truck for goods from nearby farmers. Happy to help his neighbors, he dropped off product samples and price lists with his regular wholesale customers.

“We started from a need,” Giles says. “Getting more value and getting it delivered to New York City.”

Nina Sparling

Nina Sparling Unlike a traditional distributor, the Hub doesn’t buy products up front—in fact, it never purchases anything from its member-farms

In 2012, he decided to build this ad-hoc operation acting as both the marketing and distribution agent for a handful of nearby farmers into a business in its own right. Two local organizations, the Center for Agricultural Development and Entrepreneurship (CADE) and the Watershed Agricultural Council (WAC), provided key support for Giles as he built out the Hub: access to grants and equipment, logistics strategy, and community outreach. The first meetings Giles held with local farmers at CADE were in 2012. In 2016, the Hub brought in $800,000 in on-farm sales—the Hub itself netted about $120,000 in profit.

The Hub makes its home in a former rusty red dairy barn on Giles’ farm. Where cows once stood for milking on the lower level, the farm crew now washes and crates produce. Potatoes and root vegetables grown on the farm fill one walk-in cooler; the other houses drop-offs from Hub members awaiting downstate delivery.

Behind the walk-ins is Jackie Miskovitz’s office, Lucky Dog’s logistical home. Miskovitz runs operations for the Hub, which now relies as much on the online and over-the-phone networks she maintains as on the trucks that shuttle between Hamden and Brooklyn twice weekly. Her job is to coordinate two extremely busy sets of people: farmers and chefs, all of whom are too invested, passionate, and buried in their work to manage the details. “We have to keep a lot of chatter going,” Giles says.

Unlike a traditional distributor, the Hub doesn’t buy products up front: in fact, it never purchases anything from its member-farms. Downstate buyers receive a weekly list of available product from Miskovitz. They pick and choose what they want and then place orders directly with the farmer, who is responsible for bringing the goods to the Hub the day before delivery. “There is always oversight,” Miskovitz says after getting off the phone with an egg supplier seeking support in chasing an overdue payment.

Nina Sparling

Nina Sparling Giles’ objective with the Hub is not to produce rapid returns, but to cultivate a stable market fitted to the small farms that surround him

Twice a week, the Hub delivers to New York City. Giles just started working with Farm to Table Logistics, a delivery company operating in New York State—previously he split the driving with a friend. Giles had to find someone to take over for the winter months: he and is wife are leaving the farm for a month to visit their teenage daughter spending a year abroad in Germany.

It was unclear that the Hub could continue operating while Giles was gone—small-scale systems routinely struggle with this kind instability. Through community connections and conversations with Hub members, Giles was able to find a workaround for now. The last-minute partnership with Farm to Table Logistics will keep trucks running, and in time, Giles hopes, expand the Hub’s reach to additional cities.

For its delivery and administrative services, it charges 15 percent of the invoice total, which the wholesale buyer pays, not the farmer. This is unusual: food hubs often take a cut of farmers’ sales to guarantee revenue. While the fact that farmers manage their own orders and invoices means they can maintain higher margins, it also means more legwork. Giles and Miskovitz encourage farmers to dedicate time and energy to finding new buyers and cultivating relationships. It’s a process Ean Mitchell and Kate Cummings, owners of Chicory Creek Farm in Mt. Vision, New York and Hub members, find cumbersome. “I don’t want to call two dozen restaurants every week,” Cummings says.

The farmer involvement that Lucky Dog Hub demands is both a strength and a weakness. Reliable deliveries to New York are guaranteed, but a truck on the road and a delivery team will not amplify the marketplace on their own: the problem that companies like Farmigo have attempted to solve through bringing the farmers’ market online. Many have failed, confronted with the difficulty of achieving high returns in the low-margin businesses of small-scale farming and refrigerated trucking.

“Everyone wants to throw money at tech to solve the food problem and that’s cart before horse in my mind,” says Rebecca Morgan, executive director of CADE, which has provided support to the Hub. “We’ve seen the detritus, we know we’re not there yet.”

Farmigo’s sudden disappearance pushed Giles further into his core business: smaller orders for retail stores and smaller restaurants—a model with plenty of its own hurdles. But low margins and slow returns on investment come as no surprise to Giles and the Delaware County farming community. Local needs and knowledge take precedence over investor demands. Giles’ objective with the Hub is not to produce rapid returns, but to cultivate a stable market fitted to the small farms that surround him.

Growth for the Hub and its member farms is something of a chicken-or-egg conundrum. The Hub depends on thriving farms to grow; to grow, farms need the Hub to generate sales and increase revenue. This requires investment and time on both sides—an exchange that Shannon Mason, a sixth-generation dairy farmer at Cowbella Dairy in Jefferson, New York, takes pleasure in.

Nina Sparling

Nina Sparling The growth of Shannon Mason’s dairy business has been slow, steady, and rooted in her capacities as a small-scale farmer

The Hub was her first distribution downstate, and it has provided a critical source of income for her farm. “It doesn’t make as much economic sense for a traditional distributor to stop at all of these little tiny places across the countryside picking up small amounts of product,” Mason says.

Value-added goods are Mason’s literal bread and butter. Unable to break even by selling her milk into commodity markets, Mason has prioritized growing this side of her business—a cue she takes from her great-great-grandmother, who started making butter after her husband died suddenly, leaving her with a dairy farm and several kids. The butter she started making won a prize at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The award still hangs in the farmhouse.

Mason bottles whole milk, and makes yogurt, kefir, and both sweet cream and salted butter. The goods sell in two very different marketplaces. Grocery stores upstate, among them Price Chopper and Whole Foods, buy most of the milk, kefir, and yogurt. Her dad manages those local deliveries, spending several days a week driving from supermarket to supermarket. But Mason sells almost all of her butter through the Hub, without which she wouldn’t be able to access the New York City buyers more amenable to the prices she charges for the product.

The increased revenue from Hub sales pushed Mason to explore avenues for expansion: her creamery operation had begun to outgrow itself. Around that time, a nearby fellow dairy farmer at Bovina Valley Farms (and now her husband, Dan Finn) proposed a business partnership.

Dan and his brother John had decided to turn the long-defunct dairy in the town of Bovina Center into a creamery once again. When the building came up for sale in 2016, the Finn brothers jumped at the opportunity. The facility, which had been making butter and powdered skim milk, had closed in 1973 as local dairies grew in size to meet distributor demands. His brother invested in the property and equipment, Dan planned to direct all of his milk into the creamery. Mason joined as a third partner in the project—she would contribute her milk and brand.

“There is this desire to take control of your milk,” Finn says, as he introduces me to the machines that had yet to be properly installed in the new facility: a butter press, a bottler, a yogurt packager, and (the most elaborate) a mechanized mozzarella-making machine with a feature that shapes the pulled curd into bocconcini. The creamery is organized around butter production. The additional cheeses and yogurts that Mason and Finn intend to make all use part-skim milk, leftovers of the butter making process. They hope to begin production cycles before the spring this year, packaging everything under the Cowbella brand.

The growth of her dairy business has been slow, steady, and rooted in Mason’s capacities as a small-scale farmer. In the Lucky Dog Hub, Mason found a distribution service that matched her needs and values—a business that worked better because it was small-scale and not likely to fall victim to investor demands for big, swift returns. As the creamery opens in the coming months, the Hub will begin to sell its new products. Mason hopes to sell to more retail stores in New York City (she mentions Fairway, Eataly, and Fresh Direct as targets) and expand her base of restaurants.

For both the Hub and the new creamery facility, growth entails strengthening the existing supply chain grounded in the local community. And that also means resisting the relentless pull of scale. Neither Giles nor Mason intend to extend beyond statewide distribution. The creamery, like the Hub, is an investment in the regional economy.